New Zealand Official History , Alam el Halfa and Alamein - Ronald Walker

CHAPTER 32

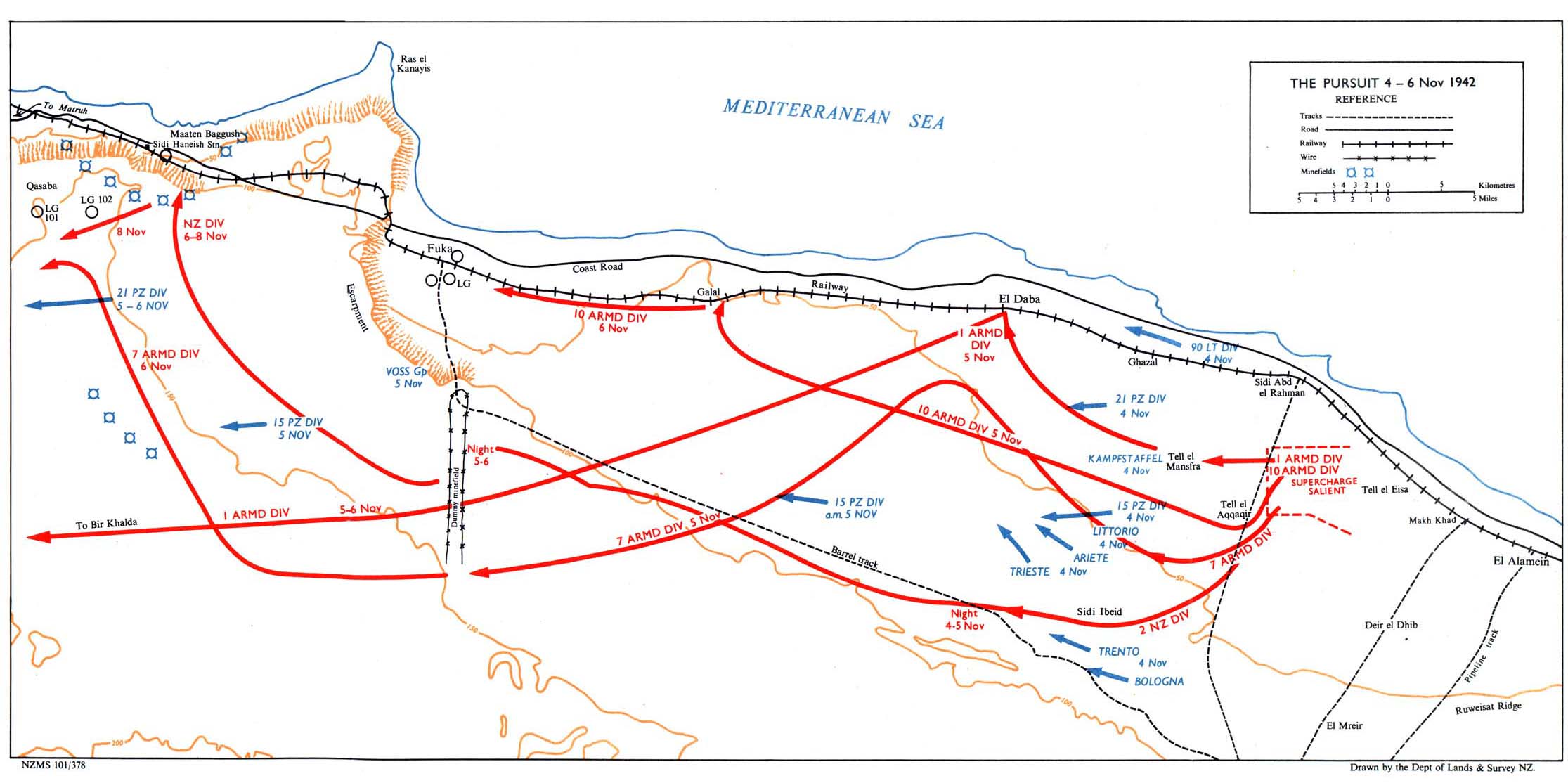

The Pursuit

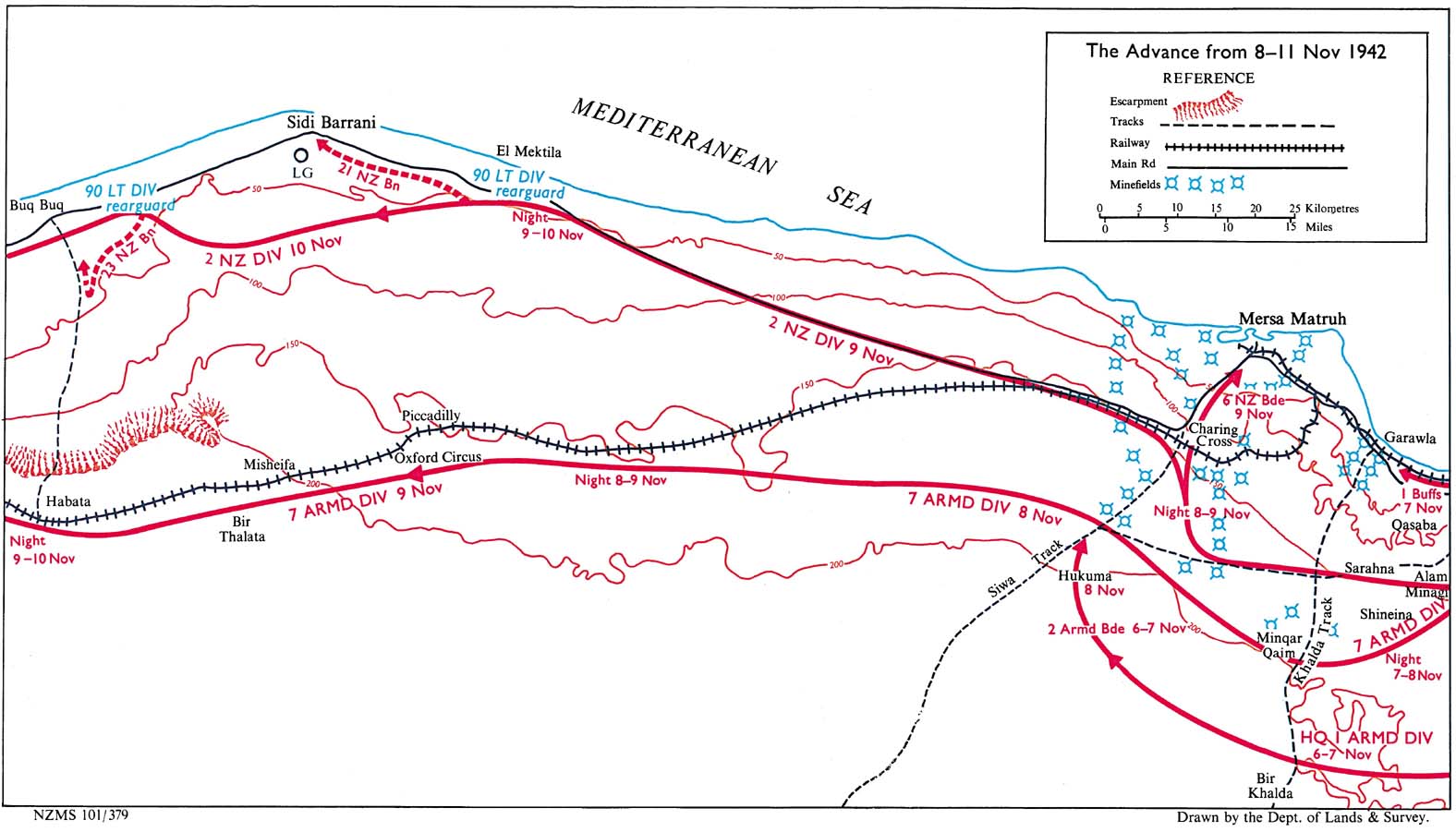

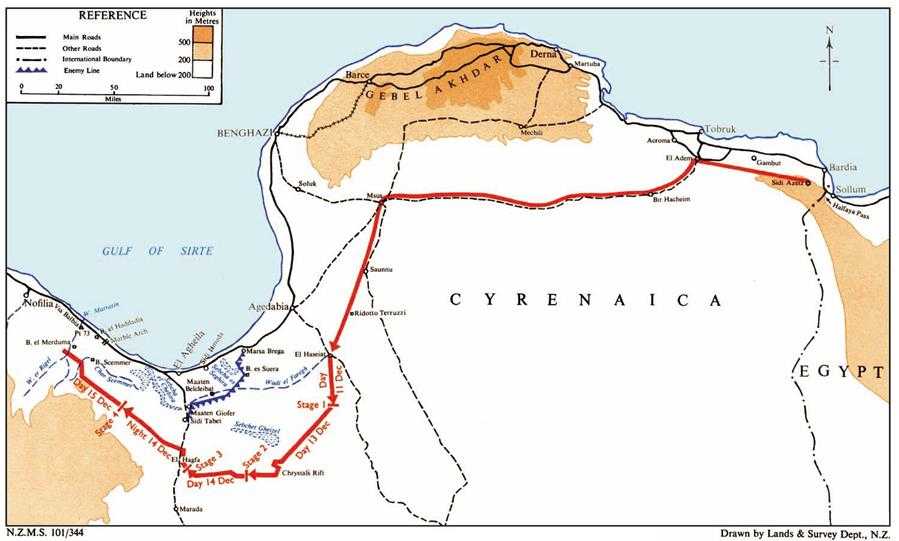

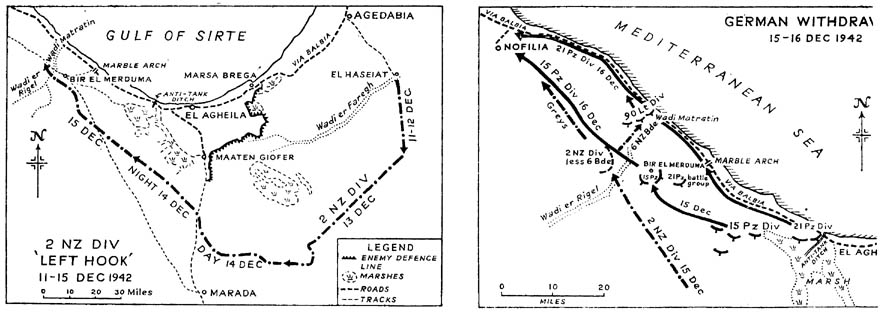

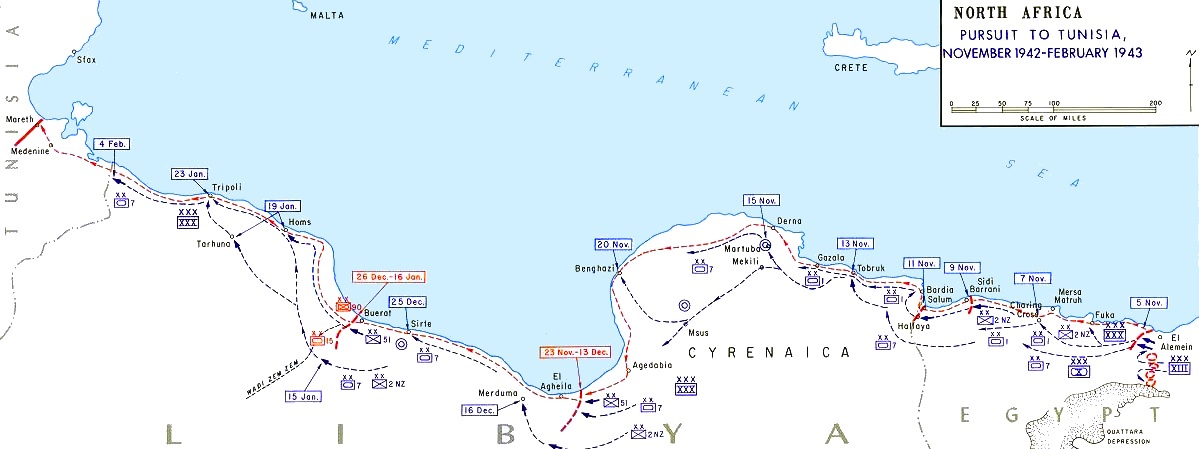

AS day dawned on 4 November, the set-piece battles of Alamein were finished. Montgomery could justly claim that his forecast of a twelve-day dogfight, to crumble the Panzer Army’s fixed defences, had proved true.1 It was perhaps fortunate that the British armour, in spite of its repeated attempts, had not managed to break out earlier as the planning had envisaged, for this failure had prolonged the battle of attrition in the form in which the Eighth Army had the advantage. When, after the false start interrupted by Hitler’s order, Rommel at last managed to get his army moving on the now unavoidable withdrawal, it soon became clear that, had the Panzer Army fallen back earlier when it still had cohesion and control, the British advance might have been slow and laborious. Montgomery has indicated in his writings that such an advance was in his mind, an advance consisting of bringing his superior weight of tanks and artillery methodically against each bound of withdrawal taken up by Rommel and, in fact, such was his method later. But in the initial stages of the enemy withdrawal, the inherent weaknesses in the Eighth Army became obvious. The British armour, as Montgomery had feared, ‘swanned’ about the desert, out of coordinated control in several fruitless encircling movements, while powerful armoured columns were at times held up by weak German rearguards which resisted only because they had no petrol for further withdrawal.

As one army fell back in some confusion and the other followed up across a desert noteworthy for its lack of easily recognisable landmarks, it is only to be expected that records of movement and event should be hazy in details of time and place. Many of the Panzer Army’s surviving records are reconstructions made after the originals were destroyed, deliberately or by battle, and cannot easily be correlated with the Eighth Army’s accounts of running fights and rearguard actions.

The day broke with a ground mist hiding much of the front. Though news of the occupation of Tell el Aqqaqir had been passed around, no one on the British side knew whether the mist would lift to disclose the congestion in the SUPERCHARGE salient to enemy fire.

When the mist dispersed shortly after the sun arose, it became obvious that the enemy had gone except for some distant guns on the north-west which fired on Australian patrols and sent some random rounds towards 6th New Zealand Brigade and the Maori positions. The German records disclose that on the northern flank 90th German Light Division, under orders to prevent a breakthrough along the coastal road, had placed rearguards about Sidi Abd el Rahman while its main body withdrew on Ghazal. South of the road and covering a front of about five miles, 21st Panzer Division mustered possibly twenty tanks in battle order. Next, on an inconspicuous rise known as Tell el Mansfra, the Africa Corps Headquarters Battle Group (Kampfstaffel), with no more than ten ‘runners’ at the most, sat slightly in advance of its neighbours. Some six or seven miles to the west of Tell el Aqqaqir, 15th Panzer Division had as many as 27 ‘runners’ and the 17 survivors of Littorio Division. Still further south, and probably to the west of Africa Corps’ north-south line, remnants of Ariete Armored Division had joined the survivors of Trieste Armored Division, the two divisions coming under 20th Italian Corps and mustering probably over 100 tanks, many of which, however, were in immediate need of repairs and maintenance. To the south of this armoured front, troops of Trento and Bologna divisions of 21st Italian Corps were supposed to be holding a position by Sidi Ibeid but, without transport, ammunition, or stores, were in fact in complete disorder.

Montgomery’s provisional plan of the previous day had been for the New Zealand Division with its attached armour, under command of 30th Corps, to follow the route taken by the armoured cars of the Royals and South Africans in a wide encircling movement round the south of Aqqaqir to gain the Fuka escarpment pass some 45 miles to the west, while 10th Corps’ armour made a shorter and sharper wheel of 10 to 15 miles to cut the coast road about Ghazal. In this way he hoped to bottle up the rearguard, in which he assumed the panzer forces would play the major part, against the coast while the New Zealanders cut off the fleeing remnants of the infantry. Lumsden, whether with Montgomery’s agreement or not is uncertain, had intimated to his divisional commanders that they might be directed on Fuka but, during the night, as the attacks towards Aqqaqir were proceeding, he issued an instruction for an advance merely to outflank the enemy without specific directions. All the evidence shows that, up to this time, no one in the Eighth Army had an inkling of the disorganisation caused by Hitler’s order and Rommel’s indecision in disobeying it, or of the low fighting state to which the Panzer Army had fallen. The resistance met by 9th Armoured Brigade in the SUPERCHARGE operation was still fresh in the armour’s memory.

As far as can be ascertained, the orders on which the armoured divisions acted were for 1st and 10th Armoured Divisions, on right and left respectively, to probe west from the salient while 7th Armoured Division advanced to the south-west across Aqqaqir, prepared to swing north against the flank of any opposition met by the other formations.

Montgomery’s desire to fight a tidy battle was this morning flouted by circumstances. By following the precept of concentrating his attack at one point, he had channelled all his mobile forces, with their massive attendant tails of support, administration and supply columns, along the tracks leading into and through the narrow salient. When word got around that the enemy had gone and the advance was starting, groups of vehicles tried to press forward to be in at the kill while others, obediently awaiting definite orders, blocked the tracks. The confusion and congestion, already bad, reached a peak this morning and it was only by the exertions of the control posts, aided by senior officers, that some sort of traffic order was gradually made out of the chaos as the day wore on.

One of the first to find his way clear of the confusion was General Freyberg’s 2nd New Zealand Division who, fully convinced that the enemy had ‘cracked’, hurried out with a small reconnaissance group to test the route round the south of Aqqaqir. Impatient orders to get the divisional column following in his wake brought the news that 4th Light Armoured Brigade, due to take the lead, was still near Alamein station jostling for its share of the tracks; 5th NZ Brigade was waiting at the base of the salient for the light armour to pass, while 9 Armoured and 6th NZ Brigades were still in the defences on the north-west corner, the latter waiting for its transport which was held up in the rear.

In the salient itself, all three armoured divisions had begun to assemble at first light in columns which at points intersected each other. About 6.30 a.m. 11 Hussars led 7 Armoured Division towards Aqqaqir, but the need to sort units from the congestion in the morning mist, as well as patches of heavy going on the route, delayed progress so that it took nearly two hours for the head of the division to reach the ground won overnight by 5th Indian Brigade. Further north, 1st Armoured Division managed to get itself in some sort of order by the time the mist dispersed and then, about 7.45 a.m., 12nd Lancers cautiously advanced due west at the head of 2nd Armoured Brigade. On Lumsden’s order, 10th Armoured Division began to assemble facing west on 1st Armoured Division’s southern flank but did not move immediately. Shortly after eight o’clock the armoured cars of 2nd Derbyshire Yeomanry, followed by the Royal Scots Greys of 4th Light Armoured Brigade, managed to thread their way out of the confusion to a point south-east of Aqqaqir, but here Freyberg held them back until the rest of his force could be organised.

The order of battle of the main components of 10th Corps’ pursuit force was:

1st Armoured Division :

-2nd Armoured Brigade

-The Bays

-9th Lancers

-10th Hussars

-Yorkshire Dragoons (motorised infantry)

-7th Motor Brigade (lorried infantry)

-2nd Rifle Battalion

7th Rifle Battalion

-2 KRRC

-12th Lancers (armoured cars)

7 Armoured Division :

-22nd Armoured Brigade

-1st Royal Tanks

-5th Royal Tanks

-4th County of London Yeomany

-1st Rifle Battalion (motorised infantry)

-131st Lorried Infantry Brigade

-1/5 Queens

-1/6 Queens

1/7 Queens

-11th Hussars (armoured cars)

10th Armoured Division :

-8th Armoured Brigade

-3rd Royal Tanks

-Notts Yeomany

-Staffs Yeo

-1st Buffs (motorised infantry)

-133rd Lorried Infantry Brigade

-2nd Royal Sussex

-4th Royal Sussex

-5th Royal Sussex

Armoured Car force :

-Royal Dragoons

-4/6 South African Armoured Car Regiment

-3 South African Armoured Car Regiment

Except for a little long-range artillery fire, all this initial movement by the British armour met with no organised opposition though increasing numbers of the enemy were encountered, most of whom, both German and Italian, had obviously missed the general withdrawal and, on the appearance of armoured cars and tanks, willingly surrendered.

The first clash with the enemy’s new line came in the middle of the morning when 22 Armoured Brigade, leading 7th Armoured Division, had travelled some miles down the Rahman Track from Aqqaqir and then turned to the west. At the turn it came under 88-millimetre fire. As the brigade halted to deal with this fire, the divisional commander, General Harding, ordered the rest of his column to keep going further south and swing round 22nd Brigade’s left flank. However, it soon become clear that the division was up against an extensive line of tanks backed by numerous guns, too strong to rush and too dangerous to leave menacing the division’s line of advance. Harding therefore called up his field and anti-tank guns and settled down to a long-range duel. This enemy force seems to have been mainly the 100 or so tanks of Ariete Division with 20th Italian Corps’ artillery, including some 88s, to back them up. There may also have been a few surviving tanks of Trieste Motorised Division, while the seventeen tanks left to Littorio Armored Div and positioned on 15th Panzer Division’s right flank were possibly drawn into the battle. Numerous parties of Italian infantry as well as some of 164th German Infantry Division, in process of re-forming before being distributed among the panzer formations, were also caught up in the battle. When Ariete Armored Division reported the engagement to Africa Corps, a battalion group was sent by 15th Panzer Division to fill the gap between its right flank and the Italians. The role of 20th Italian Corps was to guard the Panzer Army’s right flank against encirclement and, according to the German records, Rommel was at first confident that, with over 100 tanks, the Italians would fulfil their task.

In the meantime, 2nd Armoured Brigade of 1st Armoured Division had advanced slowly due west from the SUPERCHARGE salient and was heading for the rise at Tell el Mansfra, where Africa Corps’ Kampfstaffel, of a few tanks and anti-tank guns, was filling the gap between the two panzer divisions. With the Corps Commander, von Thoma, present in person, the battle group put up an exceedingly fierce resistance in which several British tanks were knocked out, including that of 1st Armoured Division’s commander, Brigadier Briggs, who then halted his armour while he called up his field artillery to suppress the enemy’s fire. Under both tank and field-gun fire, the enemy resistance broke, five tanks and a few guns managing to withdraw, according to the German records. The Africa Korps commander GeneralVon Thoma was taken prisoner, along with several hundred German gunners and infantrymen who were sheltering in nearby trenches. Though the engagement ceased and von Thoma was captured shortly after midday, 2nd Armoured Brigade does not appear to have advanced much further in the afternoon, possibly through meeting fire from the panzer divisions on its flanks.

Gatehouse’s 10th Armoured Division, comprising 8th Armoured Brigade and 133rd Lorried Infantry Brigade, had meanwhile assembled during the morning and, having extricated itself from the confusion in the salient, reached the Rahman Track just to the south of 1st Armoured Division’s line of advance by midday. Lumsden then decided that, as both 1st and 7th Armored Divisions seemed likely to be held up, Gatehouse should attempt an encircling movement to the south, though this meant that his columns would have to cut across the routes being used by 7th Armoured Division and the New Zealanders. However, enemyJU-87 Stuka dive-bombers put in one of their rare appearances this day, causing the division to disperse in some confusion, and it was late in the afternoon before 8th Armoured Brigade set off down the Rahman Track. Then, coming in sight of 22nd Armored Brigade’s battle off to the west, the brigade halted to reconnoitre and finally laagered for the night about three miles west of the track.

By the end of the 4th, therefore, the three armoured divisions of 10th Corps had advanced only a few miles west of the line gained in SUPERCHARGE. Unaware of the true state of the Panzer Army, General Lumsden was in fact following the original policy laid down by Montgomery in which the armour, after breaking out, was to position itself to invite armoured counter-attack. It was on this policy that the shallow outflanking movements of the armour were based.

Had the Africa Corps stayed to fight to the last, this method would have paid off. But what the Eighth Army could not, and did not, know was that, shortly after von Thoma’s capture, Rommel’s common sense finally overrode his loyalty to Hitler. Although neither 21st nor 15th Panzer Division had been directly engaged, reports of massed tanks facing them and attacking 20th Italian Corps on the southern flank caused him to issue in mid-afternoon an order that there was no longer any need to hold out to the last man or to permit unnecessary sacrifice, an order which may have reflected his personal feelings over the loss of von Thoma. He then issued detailed instructions for a withdrawal at dusk to a first bound on a line running south from Daba, where the formations were to set out strong rearguards to cover further retreat to the Fuka area. Both these bounds were for assembly and reorganisation, with no suggestion of prepared lines of defence. It is clear that Rommel was waiting to see what he could salvage of his army and what the British would do, and he hoped, or believed, that they would follow up as cautiously as was their custom.

However, there was one man in the Eighth Army who was impatient for bold action. Having gone forward and personally seen the quantities of guns, vehicles and equipment both destroyed and abandoned, and the groups of dispirited prisoners accumulating in ever increasing numbers, General Freyberg was sure that the enemy was on the point of slipping away and was fretting to get his divisional column on the move. Whether he expected to carry out the major encirclement of the Panzer Army unaided is unlikely, but he certainly hoped to block its retreat in time to allow 10th Corps to finish it off. His orders from 30th Corps were for a fast advance, avoiding engagements, on a line south-west from the salient to Sidi Ibeid, and thence north-west along the old Barrel route to the Fuka escarpment and north to Fuka itself, a total distance of some 60 miles. He was warned that at Fuka he might be cut off and have to be supplied by sea, a warning that illustrates the thinking of the time.

In spite of his impatience, Freyberg had first to assemble his force, a task made no easier by the congestion on the salient routes. The Division’s order of battle, with the approximate positions of the various components early on the 4th, was as follows:

HQ 2 NZ Div (Main HQ to the rear of the salient, and Tac HQ on the move forward)

HQ 2 NZ Div Sigs

9 Armd Bde in support of 6 NZ Bde in the north-west and north of the salient

Warwick Yeomanry Composite Regt

4 NZ Fd Regt

31 NZ A-Tk Bty

41 NZ Lt AA Bty

6 NZ Fd Coy

166 Lt Fd Amb

2 NZ Div Cav in the salient and to the rear

4 Lt Armd Bde moving forward from its laager about three miles east of Alamein station

Royal Scots Greys

4/8 Hussars

2 Derby Yeomanry

3 RHA

1 KRRC

Fd Sqn, RE

Lt Fd Amb PAGE 432

5 NZ Inf Bde between Alamein and Tell el Eisa except for 22 Bn (in the rear of the salient), 28 Bn (on the north flank), and artillery and other detachments scattered through the salient and by brigade headquarters

21 NZ Bn

22 NZ Bn

28 NZ (Maori) Bn

5 NZ Fd Regt

32 NZ A-Tk Bty

42 NZ Lt AA Bty

2 Coy, 27 NZ (MG) Bn

7 NZ Fd Coy

Coy 5 NZ Fd Amb

6 NZ Inf Bde in the north-west defences of the salient

24 NZ Bn

25 NZ Bn

26 NZ Bn

6 NZ Fd Regt

33 NZ A-Tk Bty

43 NZ Lt AA Bty

3 Coy, 27 NZ (MG) Bn

8 NZ Fd Coy

Coy 6 NZ Fd Amb

27 NZ (MG) Bn (less two companies) with Main HQ 2 NZ Div

7 NZ A-Tk Regt (less three batteries)

(Note: Four platoons of 4 NZ Res MT Coy were needed to make the infantry of 5 Bde mobile, and three platoons of 6 NZ Res MT Coy had to drive through the salient to pick up 6 Bde’s infantry.)

The Division’s original orders were for 4th Light Armoured Brigade to deploy at 8.30 a.m. on the east of Tell el Aqqaqir, ready to advance to Sidi Ibeid. The Warwickshire Yeomanry Composite Regiment of 9th Armoured Brigade with the Divisional Cavalry was to assemble by nine o’clock and await orders, while Main Headquarters, the Reserve Group and 5th NZ Brigade were to be ready to move by ten o’clock and 6 Brigade by midday.

As earlier related, some of 4th Light Armoured Brigade reached its deployment area on time, but the whole of the brigade was not assembled until after ten o’clock. Freyberg meanwhile had been trying without much success to get information on the progress of 10th Corps, but he at least knew from his own reconnaissance that 7th Armoured Division had met opposition close to his proposed line of advance. Some time after 10.30 a.m. he sent the armoured cars of the Derbyshire Yeomanry to find a route round the south of the battle and later despatched the tanks of the Royal Scots Greys.

Gradually throughout the day the various groups of the New Zealand force assembled and threaded their ways through the congestion and the gaps in the minefields before opening out into widely

dispersed desert formation. In his diary Freyberg described the gaps as

“feet deep morasses of dust which spouted up in front of and into the vehicles. By this date thousands of vehicles and hundreds of guns and tanks had pounded the loose fine-grained surface of this part of the desert into something resembling discoloured flour. What will it be like if it rains? 9th Armd Bde and 5th NZ Bde moved up and the congestion of vehicles in the forward area would have done credit to Piccadilly. Fortunately the RAF ruled the skies. Div [Headquarters] moved up at 1100 hours and squeezed into the crush….1”

Though many of the divisional groups moved up along Boomerang and Square tracks, it is uncertain exactly where they broke out into the open, but their guiding sign was the black diamond used to mark the Diamond track which led into 6th NZ Brigade’s defences. From somewhere near the end of this track a party of New Zealand divisional provosts with engineers had set off early to find a minefree route, which led in a southerly direction round the east of Aqqaqir and then turned north-west along the path of the reconnaissance group of 4th Light Armoured Brigade. At first these ‘Diamond signs’, of black painted tin set on iron pickets, were placed at frequent intervals, but once in the open one sign sufficed for every 700 yards. Thus marked, the Diamond Track eventually stretched from Alamein to Tripoli.

Shortly after midday 4th Light Armoured Brigade reported to Divisional Headquarters that the Greys in the lead had halted against opposition. At this time Freyberg was holding a conference with his brigadiers, but before the conference broke up the Greys had signalled that they had taken the surrender of 300 prisoners with 11 guns. It would appear that, on swinging round the south of the Italian tanks which 7th Armoured Division was engaging and then turning to the north-west, the Greys had come under fire from the 20th Italian Corps artillery sited behind the tank line. The Italian artillery had put up a token fight, but had soon ceased fire once the Greys worked round to the rear.

At the divisional conference Brigadier Gentry of 6th NZ Brigade proposed an all-night advance to reach Fuka by the early hours of the morning, asserting that the men of the Division had waited for three years for such a victory as was now offered and would willingly endure the strain of a long night drive. Kippenberger of 5th NZ Brigade was more cautious, fearing that in the dark and unknown going, the formations might become separated and be left in some confusion by morning. Freyberg himself was full of confidence that the enemy was on the point of breaking and, though 7th Armoured Division was still fighting not far away, he decided to get his column clear of the confusion and the fighting, and out into the open desert where concentration would be easier. He therefore set off with his Tactical Headquarters to catch up with the light armour, leaving orders for the rest of the force to follow as soon as possible. Main Headquarters, the Reserve Group, 5th NZ Brigade and 9th Armoured Brigade cleared the minefields by late afternoon but 6th NZ Brigade, having to wait for its transport to negotiate the congestion in the salient, did not get going until 6 p.m.

Carrying eight days’ water and rations, 360 rounds for each field gun, and petrol for 200 miles, the New Zealand vehicles, though heavily laden, made good progress once they drew clear of the powdered sand of the battle area and reached the hard sand along the Barrel Track. Of the journey, Freyberg, riding on the outside of his Stuart tank, entered in his diary:

"… we began to pass through enemy positions and tanks of the Panzer Divisions which will fight no more, burning transport, and large calibre guns. It was a change much appreciated to speed across open desert away from the dust heap of the Alamein front. As the Div swept south-westwards the guns of the tanks and arty were in action to the north where the British armour were fighting the Panzer rearguard. 4 Lt Armd Bde was ahead. Behind them marching apparently quite cheerfully were columns of PWs with a solitary armoured car or truck as an escort, carrying a few wounded and a single guard armed with a Tommy gun. We passed an infantry [? artillery] position almost intact with guns in position and ammunition boxes empty….1

During this afternoon, 22nd Armoured Brigade continued its action against the Italian 20th Corps until dark but it is hard to say how this battle really went. The German records, including Rommel’s own account, give the impression that Ariete Armored Division, fighting gallantly to the last tank, was completely surrounded and annihilated. Yet 22nd Armored Armoured Brigade claimed only 29 tanks destroyed and 450 prisoners, against a loss of one tank and a few casualties, while events next day indicate that quite a large part of the Italian force managed to disengage overnight. The Italian stand at least deterred 10th Corps from the encircling movement Lumsden had proposed and allowed Africa Corps an unimpeded withdrawal overnight.

Some ten miles past Sidi Ibeid and 15 miles due south of Daba, Freyberg halted 4th Light Armoured Brigade as dusk was falling, to allow the rest of the divisional force to catch up. Though the commander, Brigadier Roddick, wanted to carry on to the Fuka escarpment, Freyberg had learnt through 30th Corps of an intercepted message that 15th Panzer Division was also making its way to Fuka.

Liaison officers were sent back to find the other formations and, by the use of wirelessed directions and flares, 5 Brigade was guided to the laager by midnight. No sooner had this brigade halted than a minor battle ensued at the tail of its long column. A party of Germans approached one of the rear vehicles apparently to ascertain if the column was friendly or hostile, and the signals officer in the truck did his best to make them believe he was Italian. As the enemy moved off apparently satisfied, this officer went forward on foot to warn 23rd Battalion ahead, but before he could regain his truck firing broke out and a rather wild battle ensued. The mortar platoon of 23rd Battalion took the initial brunt of the fighting, first using rifles and then getting their mortars into action against fire from automatic weapons, and probably from a light anti-tank or infantry gun which accounted for one of the mortars. Carriers and 4th Light Armoured Brigade’s tanks, as well as infantry of 23rd and 28th Battalions, then joined in, upon which the enemy withdrew, taking eight men of the Divisional Signals with them as prisoners, and though chased by several vehicles, got clean away. It was later estimated that the enemy party was about seventy strong, probably a group of Ramcke parachutists searching for transport or petrol. The alarm brought some indiscriminate firing, even Divisional Headquarters some distance away coming under fire, and casualties were recorded as 8 men killed, 5 missing, 26 wounded and 8 taken prisoner; of these last, seven subsequently were recaptured or escaped. The enemy left 17 bodies behind.

Freyberg had been under pressure from Roddick and other enthusiastic members of his staff to continue the advance through the night, but this small battle convinced him of the need to get his force concentrated and organised before going any further and he decided to wait for the rest of the force. The firing had set alight an ammunition truck belonging to 23rd Battalion and this continued to blaze for some hours, providing a handy beacon for 9th Armoured Brigade and 4th Field Regiment when they drew near the divisional laager. It was still burning when, only two hours before dawn, the head of 6th NZ Brigade’s column arrived.