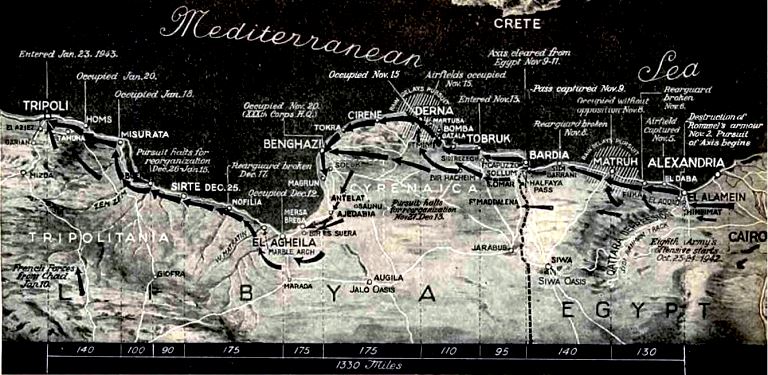

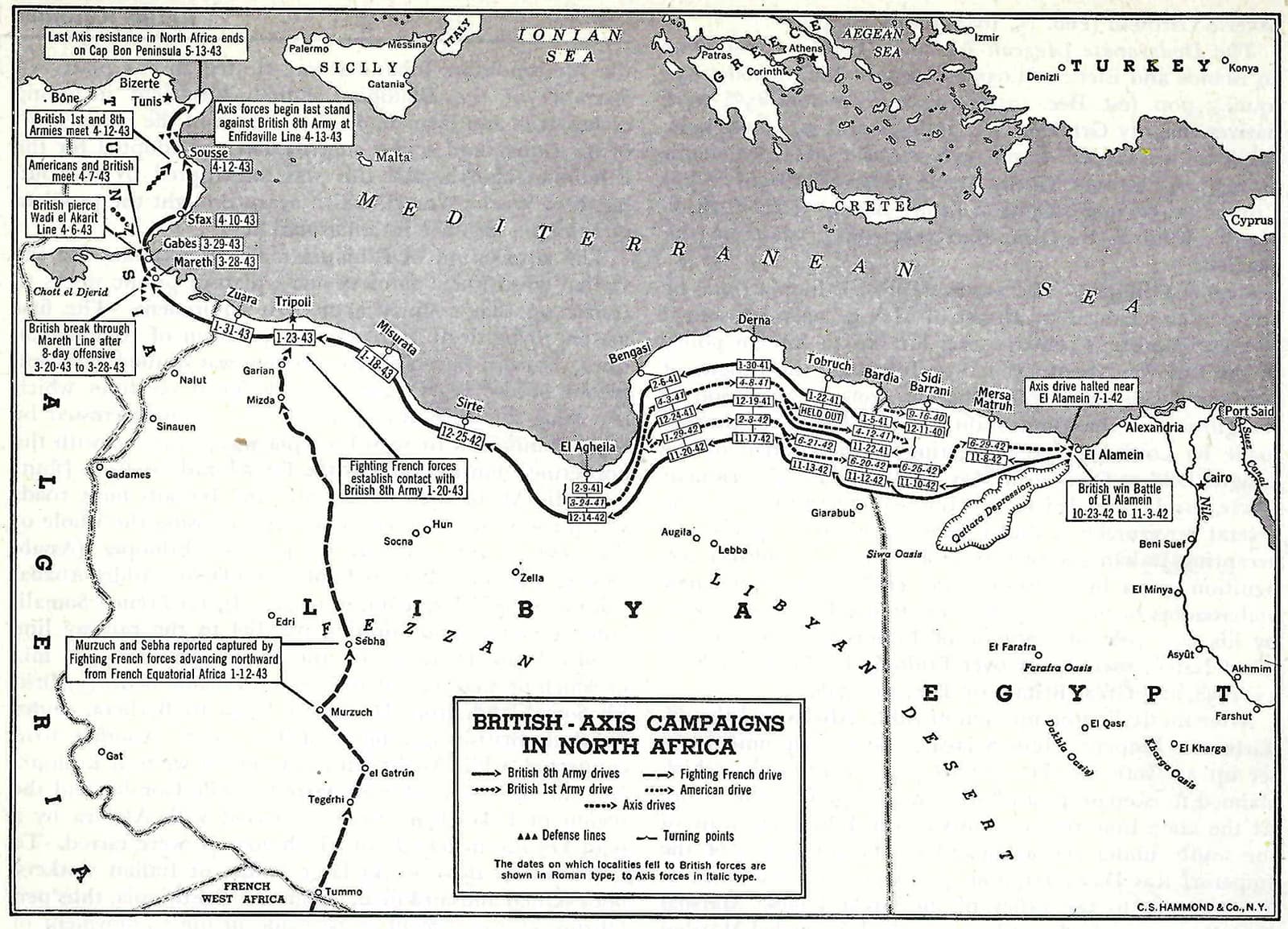

“Bardia to Enfidaville” by Major General W.G. Srevens

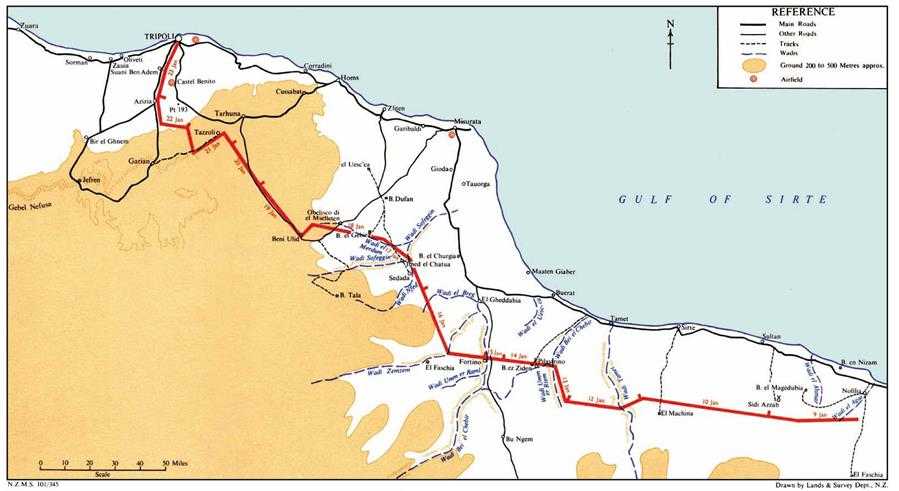

Chapter 6: ‘On to Tripoli’

15th January

AFTER moving forward during the night 51st (Highland) Division made contact on 15 January with the enemy line and prepared for a night attack. In the southern sector 7th Armoured and 2nd New Zealand Divisions were more mobile. General Freyberg, accompanied by the CRA (Brigadier C. E. Weir), spent the day with Tactical Headquarters, which was shelled at intervals. An officer and three men of the protective troop were wounded.

New Zealand Divisional Cavalry crossed the start line at 7.15 a.m. and reported its first bound clear twenty-five minutes later. This was a ridge immediately west of the Bu Ngem track. At the same time 7th Armoured Division found that the Dor Umm er Raml ridge on its front was held by Axis anti-tank guns. Thus it was not surprising that when NZ Divisional Cavalry advanced to its second bound, the western edge of Dor Umm er Raml, it encountered an infantry and anti-tank screen, and that A Squadron was held up. B Squadron moved off in an attempt to work round the enemy’s southern flank, and in this was partly successful, destroying a German 75-millimetre gun in the process.

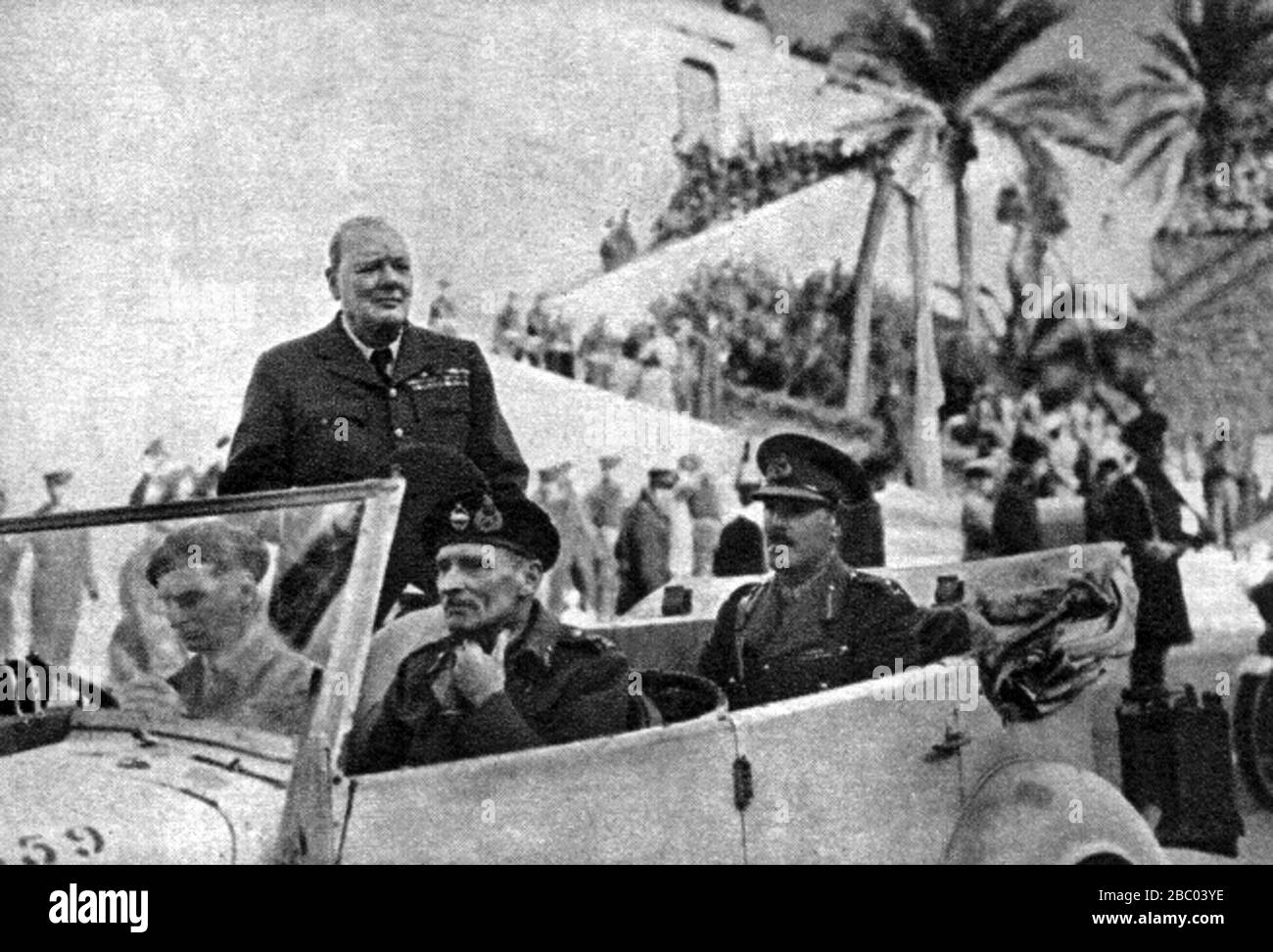

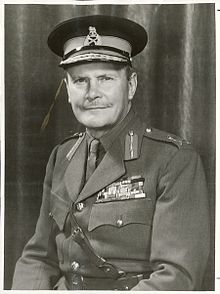

General Bernard Freyberg , Commsnder of 2nd NZ Division , nicknamed as “Salamander” by Churchill

By about 9.30 a.m. the enemy was seen to be in strength sufficient to hold up the advance for some hours. His shelling was particularly heavy. Freyberg therefore altered the thrust line 30 degrees to the south to turn the enemy’s flanks and called the Greys forward as a complete regiment to move behind Divisional Cavalry. The 211th Medium Battery and 4 Field Regiment were also brought forward from the Reserve Group.

On this new thrust line Divisional Cavalry gradually worked round the end of the ridge, helped by some good shooting from 34 Anti-Tank Battery and a troop of 26 Field Battery. About midday the GOC ordered the Greys to follow, but on a personal reconnaissance found the going heavy and about 3 p.m. reverted to the original thrust line. By late afternoon Divisional Cavalry and the Greys were round the end of Dor Umm er Raml and had engaged enemy tanks and transport on the western side. Both units

laagered for the night on the southern slopes of the ridge. In the last spurt of enemy shelling at dusk several more casualties were added to the day’s small total.

The rest of the Division advanced slowly without coming into action. Fifth Infantry Brigade Group could not move at all until 2.50 p.m., and was still east of the Bu Ngem track at the end of the day. By nightfall only some eight miles had been gained and, in the words of the GOC, ‘progress was slow’. From his prepared positions the enemy probably had the better of the engagement; but on the whole Freyberg was satisfied, for the pressure played its part in deciding the enemy to draw back. Nevertheless the objectives for 15 January, Sedada and Tmed el Chatua, were still a long way off.

The tanks of 7th Armoured Division were in action during the day and inflicted losses on the enemy, but at some cost to themselves. The 4th Light Armoured Brigade finished the day well to the south-west, with the Royals near El Faschia, which was still in enemy hands.

At the end of the day the GOC learnt that 30th Corps would resume the advance to Sedada at first light next morning.

The Enemy on 15 January

The action of 4th Light Armoured Brigade had been vigorous enough to force 33rd German Reconnaissance Unit’s southern outposts back towards El Faschia, where there was an Italian garrison. On Dor Umm er Raml 15th Panzer Division, with 3rd German Reconnaissance Unit on its right, resisted attacks all day and claimed to have inflicted heavy losses on British tanks. The reconnaissance unit reported during the morning that it was in action against a strong enemy force (2nd NZ Division) and later that it had fended off an attempt to get round its flank. The German army narrative notes that about midday the Commander-in-Chief (Rommel) ordered a concentration of artillery against the British assembly areas, which no doubt explains the severity of the shelling experienced by 2nd NZ Division.

While Rommel thought that the German defence had done well during the day, he was vividly aware of some unpleasant facts. He expected Eighth Army’s attack to be intensified next day; he was outnumbered in men and his own supplies were most inadequate; and he could not offer prolonged resistance. By midday, therefore, he had already issued the codeword MOVEMENT RED, which meant that a retirement was to commence to a line running from Sedada to Bir el Churgia (20 miles north of Gheddahia), starting at 8 p.m. But the remaining Italian troops, except Centauro Battle Group, began withdrawing in the afternoon to the Homs–Tarhuna line.

16 January – across Wadi Zemzem

The Highland Division attacked at 10.30 p.m. and found that resistance gradually declined, and that by daylight on 16 January the enemy was retiring. For the New Zealand Division the next few days had an overall sameness, a steady advance over increasingly difficult country, often through clouds of dust, often with long delays, with only the most advanced troops ever seeing the enemy, and with no general deployment – altogether a rather wearisome and monotonous period. But again the engineers worked unceasingly on mine clearance, removal of booby traps, and finding ways round demolitions.

The Division began the 16th by discovering that Dor Umm er Raml was deserted by the enemy, except for a few members of 115 Panzer Grenadier Regiment of 15 Panzer Division, who appeared to have been forgotten and who were promptly captured by New Zealand infantry. Their morale was good.

The divisional column was led by the screen of Divisional Cavalry and the Greys, with Tactical Headquarters always well forward, ‘leading the field at a cracking pace until pulled up by enemy opposition at 4 p.m.’ In fact the Greys recorded that the GOC moved at twenty miles an hour and that their heavy tanks could not keep up and had to lag behind. Next after this advanced guard came a gun group of 4th and 6th Field Regiments and 211st Medium Battery. Minefields, both real and dummy, caused delay on Dor Umm er Raml and in Wadi Zemzem, and parties from both 6th and 8th Field Companies were called forward to deal with them. Wadi Zemzem basically was no obstruction. The forward troops were across by 1 p.m. and nearing Wadi el Breg, 12 miles short of Sedada.

After crossing this wadi Divisional Cavalry met heavy and accurate shelling from the direction of Wadi Nfed, on which Sedada was located. The 4th and 6th Field Regiments were both deployed, opened fire about 4 p.m. and continued until dusk. Tactical Headquarters got so far ahead that it outdistanced the Divisional Cavalry screen during this period, and captured three tanks from Centauro Battle Group. The crews, who surrendered to the GOC himself, said they were anti-German and glad to be out of the war.

As daylight faded enemy tanks increased in number, and it was estimated that there were about fifteen German and fifteen Italian. The Greys knocked out two Italian tanks and destroyed many vehicles and guns in an action lasting two hours, but had four tanks hit and evacuated. They captured some twenty prisoners. The 6th Field Regiment finished the day gloriously by capturing sixteen Germans, all from 115th Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

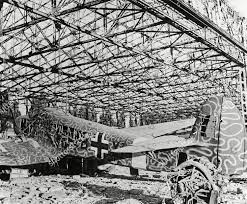

In the late afternoon there were two attacks from enemy aircraft on the forward troops of both 7th Armoured and 2nd NZ Divisions, one by twelve aircraft and one by fifteen, but no damage was done. The 41st Light Anti-Aircraft Battery shot down one raider from the first attack.

The Division had advanced about 40 miles during the day, with 7th Armoured Division keeping level on the right, despite delays on minefields. The leading troops laagered for the night between Wadi el Breg and Wadi Nfed, with 25 Battalion providing perimeter defence for the tanks. The rear of 5 Infantry Brigade was still on Dor Umm er Raml, with the Administrative Group even farther back. And Sedada had not yet been captured, although there were signs that the enemy would go during the night. The opposition had been from 15 Panzer Division and Centauro Battle Group.

The GOC held a conference at 8 p.m., mainly to confirm that the axis for next day would be Sedada–Tmed el Chatua – thence north-west to a point on the Beni Ulid–Bir Dufan road about 18 miles east of Beni Ulid named Obelisco di el Mselleten. The Division had a quiet night except for the comforting noise of aircraft passing overhead to bomb the coastal road and the Bir Dufan landing ground.

The Enemy on 16 January

During the night the enemy withdrew under plan MOVEMENT RED and by 8 a.m. on 16 January was in new positions, 90th German Light Division astride the main coast road near Churgia, 3rd Reconnaissance Unit filling a long gap between 90 Light and the Sedada area, 15th Panzer Division and Centauro Battle Group south and south-east of Sedada, and 33rd Reconnaissance Unit on the western flank falling back to Abiar et Tala, 30 miles west of Sedada. The GAF Brigade was across the coast road 25 miles behind 90th German Light Division, and 164th German Light Division and Africa Panzer Grenadier Regiment were in second-line positions round Beni Ulid.

Enemy reports show that at first it was thought that Eighth Army followed up slowly; but it appears later that the increasing pressure round Sedada was felt, and even created some alarm. Units drew on their last reserve of petrol, and were running short of ammunition. Moreover, the shortage of troops caused a serious gap between 90th German Light Division and the units at Sedada. Rommel came to the conclusion that he could not resist another day on the same line, and so ordered a withdrawal (MOVEMENT BLUE) to the general line Beni Ulid–Bir Dufan–Tauorga, to be commenced at nightfall.

The unit in real trouble was 33rd German Reconnaissance Unit, which was trying to withdraw north-west through Abiar et Tala to Beni Ulid, through very difficult country. It was both short of petrol and much harried by 4th Light Armoured Brigade. To break clear it had in the end to sacrifice many of its wheeled vehicles, and by nightfall was still many miles from Beni Ulid with only enough petrol to take its armoured vehicles 25 kilometres.

17 January – across Wadi Sofeggin

In the evening of 16 January Montgomery cancelled the caveat he had imposed and ordered the advance to proceed with great resolution and the utmost speed, for he was already a little concerned with the rate of progress. Despite 7th Armoured and 2nd NZ Divisions’ efforts the total advance in two days was not more than 50 miles, which was not enough. Montgomery now wanted to intensify the threat to Tripoli from the flanking column to cause the enemy to thin out in the Homs area, where demolitions along the road promised to be a serious deterrent to the advance there. He then intended to drive hard from his eastern flank once the enemy had drawn away.

During 17 January 51st Highland Division made fairly good progress northwards along the main road and reached Gioda, with little opposition from troops but much from mines, craters and demolished bridges. The Army Reserve, 22nd Armoured Brigade, moved forward to about halfway between Tauorga and Sedada.

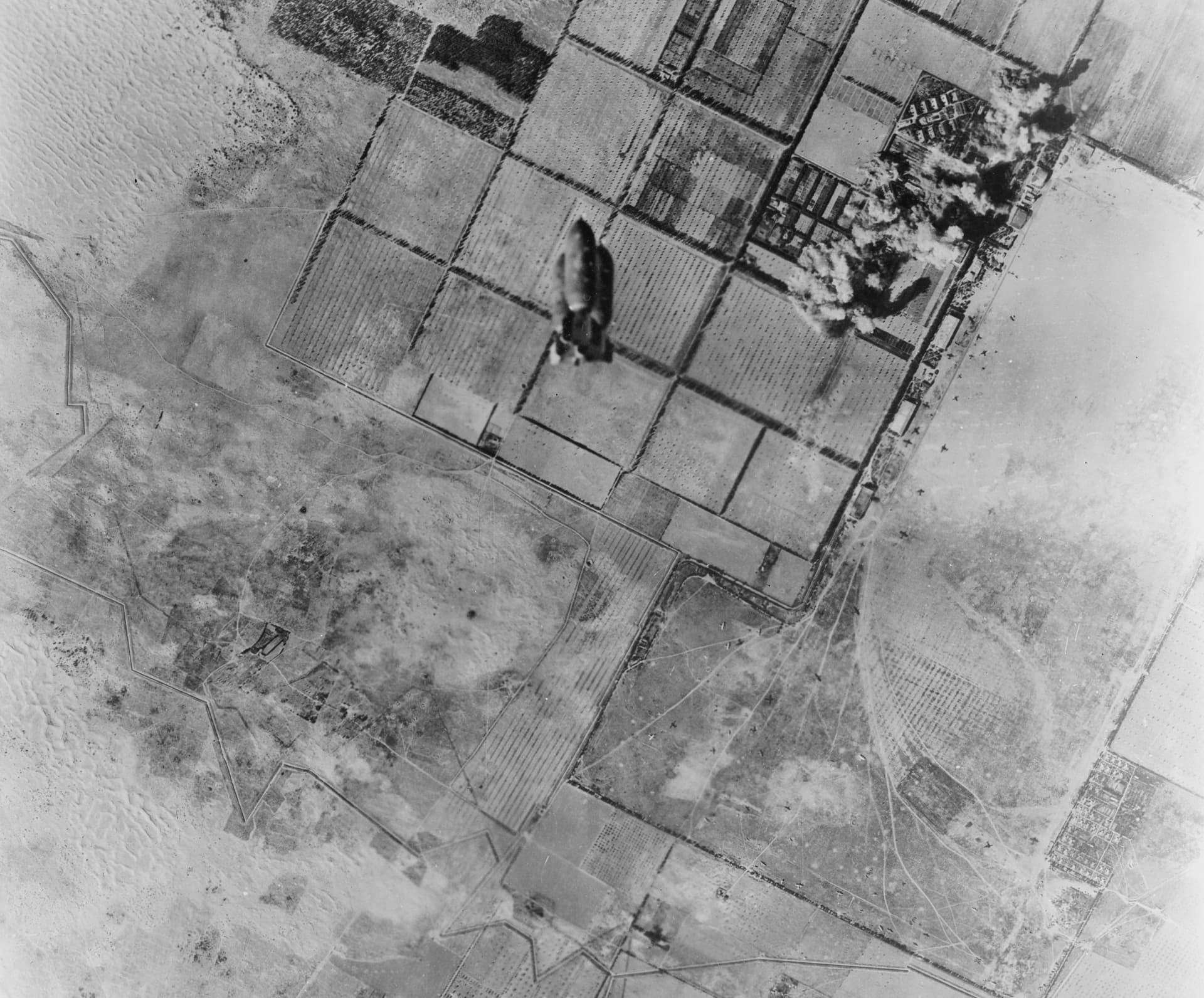

A landing ground at Wadi el Breg was completed during the day by 7th Armoured Division and was occupied almost at once by the Desert Air Force. The endless stream of transport aircraft bringing supplies reminded some of the veterans in 2nd NZ Division of the similar – but how different – picture of German aircraft streaming on to the airfield at Maleme in Crete. Times had changed. The RAF column which had been moving with 2nd NZ Division went to this landing ground, which presumably replaced the one intended for Sedada. One heavy and one light anti-aircraft battery were detached from the Division for protective duties there, and rejoined it in the morning of the 18th.

The Division advanced again about 7.30 a.m. and Sedada was soon reported clear; but the advance of the main column was delayed by minefields in Wadi Nfed, both real and dummy, which obstructed the only good track. Engineers from 7 and 8 Field Companies cleared the mines and improved an alternative track; but even then the going was rough and dusty, and movement was in single column. The engineers had their inevitable casualties from mines, but got some satisfaction from destroying a little stock of captured enemy tanks and guns. There were signs at Sedada of a hasty withdrawal, for several small minefields had not been finished, with mines still lying alongside the holes dug for them.

During the day 7th Armoured Division converged on to 2nd NZ Division’s line of advance, owing to the bottleneck across Wadi Nfed. Once during the morning the GOC adjusted the axis to give 7th Armoured Division more space; but shortly after 1 p.m. 7th Armoured Division cut across the Division’s axis and separated the leading groups from the rest. The break came in the 6 Brigade column just south of Sedada, with the result that only 24th Battalion was in touch with the armour and artillery. The mix-up was referred to 30th Corps, which ruled that 7th Armoured Division must have priority. The rear portion of 6th NZ Brigade Group and all groups behind it therefore had to halt until the armour passed through, for at the best there were only three good tracks. This caused 2nd NZ Division to fall behind 7th Armoured Division, a position it could not retrieve for several days.

The advance of the leading groups continued steadily past Tmed el Chatua, across Wadi Sofeggin and on towards Wadi el Merdum. Odd prisoners were collected, including a party of three Italians who came out of hiding and surrendered. In the late afternoon enemy aircraft again made several attacks, causing casualties in Divisional Cavalry and in the artillery numbering six killed and eight wounded.

At Wadi el Merdum the axis of advance turned westwards towards Beni Ulid. By 5.30 p.m. leading patrols had passed Bir Gebira, and when a halt was called the day’s advance was between 40 and 50 miles. Divisional Cavalry and the Greys laagered just west of Bir Gebira, with 24th Battalion, the only infantry unit available, providing protection. The rest of 6 Brigade did not arrive until almost 10 p.m.

A special plan had to be made to bring the remaining groups forward. Provost Company used 400 lamps to light the route for 40 miles. The three groups concerned, Divisional Headquarters, Reserve Group, and 5th NZ Infantry Brigade, set off about 7 p.m. and did not complete the move until after midnight.

On the left of 2nd NZ Division patrols of 4th Light Armoured Brigade were ten miles south of Beni Ulid. On the right 8th Armoured Brigade of 7th Armoured Division crossed the Bir Dufan – Beni Ulid road and advanced another ten miles to the west, a notable penetration.

The Enemy on 17 January

The 90th Light Division continued its withdrawal along the line of the main road back towards Misurata. The 164th Light Division, Africa Panzer Grenadier Regiment and Centauro Battle Group were in and around Beni Ulid. The intention was that 164 Light should act as rearguard after 15 Panzer and the reconnaissance units had passed through, for Beni Ulid was a bottleneck. This left a large gap in the German line, which GAF Brigade filled by moving across from the main road to Bir Dufan. A further gap still remained between that place and Beni Ulid and it was through this that 8 Armoured Brigade had penetrated. In front of 2nd NZ Division , 3rs German Reconnaissance Unit covered the retirement of 15 Panzer Division to Beni Ulid, and at last light was still to the east of that village. After a bad day 33rd German Reconnaissance Unit had escaped 4th Light Armoured Brigade only by the barest margin with the help of a few tanks from 15 Panzer Division.

As on the two previous nights, Rommel decided that he could not stand, particularly as his line had been breached by 8th Armoured Brigade. At 7 p.m. he gave orders for all main bodies to retire to the Tarhuna – Homs line and for the Italian non-motorised troops already there to go back to the close defences of Tripoli. These ran in an irregular line on an arc about 15 miles from the town, were by no means strong, and presented no real obstacle.

Rommel also indicated to Commando Supremo in Rome that not even the motorised formations could make an effective stand on the Tarhuna – Homs line, but would also have to move back to Tripoli, which would be threatened by 20 or 21 January. His main reason for these conclusions was the shortage of all supplies, for he considered that with better maintenance he could hold the Tarhuna – Homs line for some time. The going to the south-west, where an outflanking attack might be made, was known to be very bad – as 2nd NZ Division was to discover.

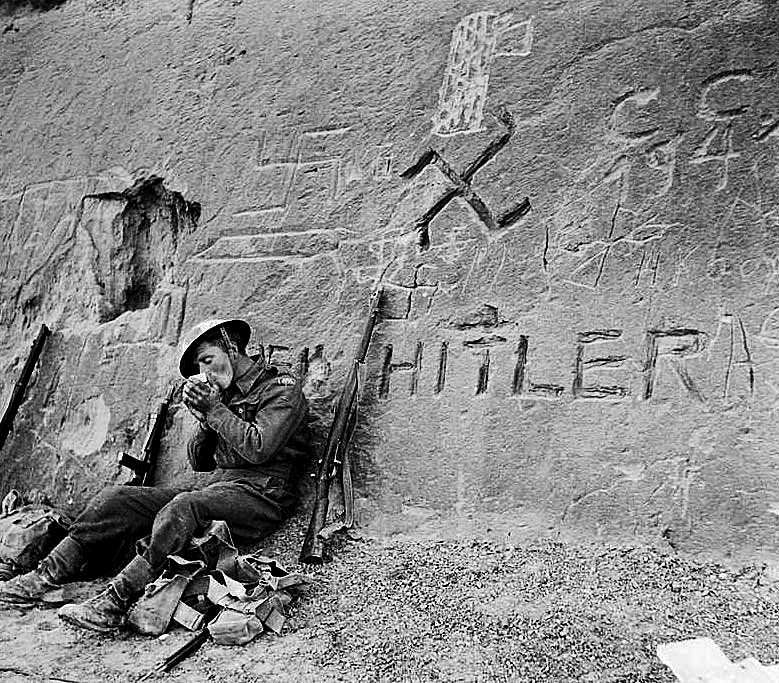

A Daimler armored car opens fire to support advance of 7th Armored Division , 18th January 1943