Brooklyn Eagle (February 12, 1943)

Editorial: Lincoln’s words inspire U.S. today as in every crisis

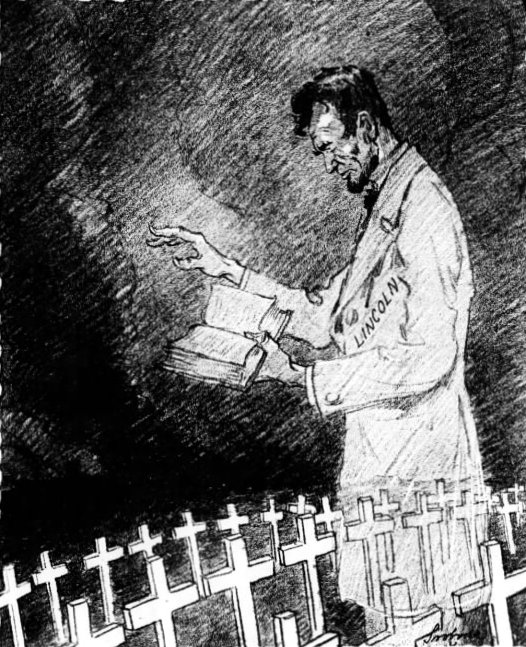

There in spirit to consecrate

Americans today, with their constantly deepening affection for the personality of Abraham Lincoln, would be heartened by the certain knowledge that their course and their conduct in a time of national crisis met with the approval of this most appealing character in the history of their country.

It does not seem presumptuous, in view of all that is known of Lincoln, as revealed principally by his own words, to conclude that this generation of Americans shares with him his faith “that right makes might,” that it is animated by “fairness in the right, as God gives us to see the right,” and that it still retains that “patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people” that he considered as essential to the preservation of democracy.

It is more than three-quarters of a century now since Lincoln died. Yet today he still speaks eloquently to those who would maintain the democratic way of life, who would place their trust in the collective wisdom and decency of the people and who hold fast to the faith that he had in the indomitable power of a nation under God dedicated to a birth of freedom. As a people, we have had that faith in the past. Happily, there is abundant evidence in the tragic and the glorious record of this last year to prove that we have it now.

No anniversary is more welcome – none comes to the American people with a more inspiring and reviving touch – than the birthday of Abraham Lincoln. This is particularly true when the nation is deep in crisis, as it is today. The reasons for Lincoln’s hold on the friendly interest and the admiration of Americans are readily apparent. He was essentially a kindly man and bitter experiences had made him understanding and tolerant of human frailty.

He knew poverty and hardship. He knew personal disappointment and unhappiness. He knew defeat. The record of lost battles from Bull Run, which was attended by the element of disgrace, to Cold Harbor would in itself have been sufficient to bring despair. He knew incompetence and treachery and venality. But he had unfaltering faith in America and in the justice of its cause and, in the end, this faith was sustained.

In the present crisis, America has not been spared the consequences of mistakes, of lack of vision, of complacency. But there has been no failure of courage, no yielding to the temptation to compromise with principles, to put aside ideals and to follow an easier road than that which has been chosen. This nation, facing the necessity of expending blood and wealth, has been true to its traditions.

Lincoln, if he were on the scene today, would be satisfied that Americans are still willing to fight and to suffer for the translation into reality of the old dream of peace and brotherhood and freedom. He would not ask for perfection, realizing that he had made his own share of mistakes and that there had been blunderers all around him. He would ask that in this dark hour there be faith and courage and determination. And with these he would be satisfied.