On January 22, at 11 a.m., general de Gaulle’s plane landed in Fédala, near Casablanca. The General was accompanied by Catroux, Argenlieu, Palewski and Hettier de Boislambert. At the airport, they are received in great secrecy by Colonel de Linarès, Mr. Codrington, and the American general Wilbur, whom de Gaulle once knew at the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre. The General’s first impressions are clearly unfavorable: there is no guard of honor, but we see everywhere American sentinels; he is driven to Anfa in an American car, housed in a city requisitioned by the Americans, where the service is provided by American soldiers, while the entire sector is surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by American sentries – all this in French territory… “In short,” wrote the General, “it was captivity.” Worse still, “a kind of outrage”.

De Gaulle was therefore in a murderous mood when he went to the lunch given in his honor by general Giraud; the first words he addresses to the latter are also sarcastic at will: “Hello, my General. I see that the Americans are treating you well.” After which he explodes: “Well, what? I have, four times, offered you to see us and it is in this wire enclosure, in the middle of foreigners, that I must meet you? Don’t you feel that what is abhorrent from a national point of view?”

General de Gaulle wrote that the meal still took place in a cordial atmosphere. In any case, he started badly: having learned that the house was guarded by American sentinels, de Gaulle refused to sit at the table before they had been replaced by French soldiers. After the meal, there is no longer any question of cordiality; Giraud repeatedly declared that he was in solidarity with the “proconsuls” Noguès, Boisson, Peyrouton and Bergeret, and that although he was determined to fight the Germans, he had nothing against the Vichy regime. As for de Gaulle, he declares quite clearly that he came against his will, and that he refuses to discuss under the aegis of the Anglo-Saxons; he also has some very harsh words for Churchill and Roosevelt. We separate very coldly, without making another appointment, and general de Gaulle returns to his villa.

In the late afternoon, de Gaulle, who had stayed at home on a calculated reserve, was visited by Mr Macmillan, who eventually persuaded him to visit Churchill, who lived in one of the neighboring villas. Churchill summed up the following interview in three words: “an icy meeting.” De Gaulle, for his part, will be more explicit: "In approaching the Prime Minister, I tell him with vivacity that I would not have come if I had known that I would have to be surrounded, on French soil, by American bayonets. “It’s an occupied country!” he exclaimed”. And Churchill explodes in turn. “I made it very clear to him,” he wrote, “that if he persisted in being an obstacle, we would not hesitate to break with him once and for all.” Which, in Churchillian French, gave exactly this: "Si vous m’obstaclerez, je vous liquiderai ! "

“Being both softened,” general de Gaulle continued, "we got to the bottom of things. The Prime Minister explained to me that he had agreed with the President on a draft solution to the problem of the French Empire. Generals Giraud and de Gaulle would be placed jointly as chairman of a leading committee, where they, along with all other members, would be equal in all respects. But Giraud would exercise supreme military command, due in particular to the fact that the United States, having to provide equipment to the reunified French army, intended to settle the question only with him. “No doubt,” said Mr. Churchill, “my friend general George could complete you as the third president.” As for Noguès, Boisson, Peyrouton, Bergeret, they would keep their position and enter the Committee. “The Americans, indeed, had now adopted them and wanted them to be trusted.”

I replied to Mr. Churchill that this solution might seem adequate to the level – which is indeed very estimable – of the American sergeant majors, but that I did not imagine that he himself would take it seriously. As for me, I was obliged to take into account what remained to France of its sovereignty. I had, he could not doubt, the highest regard for himself and for Roosevelt, without however recognizing them any kind of quality to settle the question of power in the French Empire. The Allies had, apart from me, against me, established the system that worked in Algiers. Apparently finding only mediocre satisfaction, they now planned to drown the France Combattante. But this one would not lend itself to it. If she were to disappear, she would prefer to do so with honor.

Mr. Churchill did not seem to grasp the moral side of the problem. “See,” he said, “what my own government is. When I formed it, once, designated as I was for having fought for a long time against the spirit of Munich, I brought in all our notorious Munchers. Well! They follow up hard, to the point that today they are not distinguished from others.” – “To speak like this,” I replied, “you must lose sight of what happened to France. As for me, I am not a politician who tries to make a cabinet and find a majority among parliamentarians.” The Prime Minister asked me, however, to reflect on the project he had presented to me. “Tonight,” he added, “you will confer with the President of the United States and you will see that, on this issue, he and I stand in solidarity.”

Lord Moran, Churchill’s doctor, described in his diary the end of the interview: "When they finally left the small living room of our villa, the Prime Minister remained for a moment in the entrance contemplating the Frenchman who crossed the garden with great strides, with pride. Then Winston turned to us and said with a smile:

– His country has abandoned the struggle, he himself is only a refugee, and if we withdraw our support, he is a finished man. Well, look at him! No, but look at him! One would think Stalin, with two hundred divisions behind him. I did not spare him. I told him straight that if he didn’t be more cooperative, we would let him down.

“And how did he take it?” I asked.

“Oh,” replied the Prime Minister, “he paid little attention to it. My advances as well as my threats have not produced the slightest reaction.”

That evening, President Roosevelt gave a dinner in honor of the Sultan of Morocco. Churchill is not at his best on this occasion: “He was scowling,” will wrote Hopkins, “and seemed bored firmly.” The complete absence of alcohol at this dinner may have something to do with it. After the meal, Churchill announced to Roosevelt that he “led the hard life to de Gaulle.” He suggested that Roosevelt not meet the General until the next morning, but on Hopkins’ advice, the President decided to receive him that evening as planned.

Thus, late in the evening, de Gaulle met President Roosevelt for the first time. Harry Hopkins notes that the General “arrived with a cold and stern air.” Elliot Roosevelt, who is also present, adds: “He enters with great strides […] giving us the impression that his narrow skull was surrounded by lightning.” The President, dressed in white and sitting on a large sofa, is all smiles and asked de Gaulle to take a seat at his side. The General later wrote: “That evening we stormed with good grace, but we stood, by mutual agreement, in a certain imprecision about the French affair. He, drawing with a light dotted line the same sketch that Churchill had drawn with a heavy stroke to me and gently suggesting to me that this solution would be necessary because he himself had solved it.” And he added: “[Roosevelt] was quick to bring his mind to mine, using charm, to convince me, rather than arguments, but attached once and for all to the side he had taken.”

This is also the impression that the President’s son gets, who reports the following words: “I am sure that we will succeed in helping your great country to reconnect with its destiny,” says my father, playing all his charm. His interlocutor is content to emit a growl for any answer. “And I assure you that my country will be honored to participate in this undertaking,” adds my father. “I’m glad to hear you say it,” replies the Frenchman in an icy tone.

But these are just trivialities. Elliot Roosevelt is no longer there when the serious discussions begin, because the President wanted to talk to de Gaulle one-on-one – which does not prevent one of the President’s aides-de-camp, Captain Mac Crea, from taking some notes, “from a rather uncomfortable observation point, he himself wrote, a slot in a slightly half-open door”… The President begins by saying that the whole purpose of the discussions with Churchill is to organize the rest of the war, and to agree on the choice of new theaters of operations. He then evokes the political situation in North Africa, and declares most seriously in the world that he “supposes that the collaboration of general Eisenhower with admiral Darlan caused some astonishment to general de Gaulle”. Nevertheless, Roosevelt “fully approved of general Eisenhower’s decision in this matter, and things were moving in the right direction, when the admiral died inadvertently.” Regarding the exercise of sovereignty in North Africa, “none of the candidates for power has the right to claim that he alone represents the sovereignty of France. […] The Allied nations that are currently fighting on French territory are doing so for the liberation of France, and are in a way exercising a political mandate on behalf of the French people.” In other words, France is equated with a young child who absolutely needs a guardian. “The only thing that could save France,” concludes the President, “is the union of all its good and loyal servants to defeat the enemy, and once the war is over, victorious France will again be able to exercise its political sovereignty over the Metropole and the Empire.”

From his improvised observation point, behind the half-open door, Captain Mac Crea has some difficulty following the conversation: “General de Gaulle was speaking too low for me to hear anything,” he confessed, “and so I cannot report any of his words.” In fact, de Gaulle delicately but firmly indicated to the President that “the national will had already fixed its choice and that, sooner or later, the power that would be established in the Empire, then in the Metropole, would be the one that France wanted”.

But several other witnesses also attended this conversation “one-on-one”, as Harry Hopkins noted: “In the middle of the conference, I noticed that all the members of the secret service assigned to the protection of the President were standing behind the curtain above the gallery of the living room, and behind the doors that gave access to the room; I even saw a machine gun in the hands of one of them. […] Leaving the room, I went out to talk to the people of the secret service, in order to find out what was happening; I found them all armed to the teeth, and equipped with about a dozen machine guns. I asked them why. They replied that they believed they had to take all necessary precautions so that nothing happened to the President. We hadn’t done all this circus when Giraud met the President, and it reflected the atmosphere around de Gaulle in Casablanca. The spectacle of the secret service in arms seemed incredibly funny to me, and never could a Gilbert and Sullivan play have matched it. Poor General de Gaulle, who probably knew nothing about it, was kept at gunpoint throughout his visit.”

But the president of the United States and the head of France Combattante take great care to avoid all outbursts, and after half an hour they separate, satisfied and relaxed. On the way back, de Gaulle confided to Hettier de Boislambert: “You see, today I met a great statesman. I think we got along well and understood each other.”

Nothing similar would happen during the second meeting between de Gaulle and Giraud the next morning; the latter, as could be expected, pronounced himself in favor of the Anglo-American solution, and repeated that politics did not interest him. De Gaulle tries to explain to him that he has compromised himself politically by affirming his loyalty to the Maréchal, and tries to convince him to join the France Combattante. But Giraud required supreme power, and demanded that it be the France Combattante that rallied to him. In the end, we only agree to establish a connection between the two movements, and we separate in an icy atmosphere.

It is quite clear at this point that Churchill and Roosevelt failed in their efforts to unite the two opposing factions. But it must be remembered that this is not really President Roosevelt’s goal; he only wants to give everyone – and especially American public opinion – the impression that he has succeeded in reconciling Giraud and de Gaulle, thereby silencing his many critics, in the United States as elsewhere. But all that is needed is a judiciously drawn up communiqué, signed by the two French generals. Roosevelt spent part of the night writing it, with the help of Robert Murphy and Churchill. The latter would undoubtedly have preferred a genuine reconciliation between the two generals; but it now seems impossible, and besides, he, Churchill, also has a public opinion to appease… The press release will therefore do the trick. We finally agree on the following text: de Gaulle and Giraud proclaim themselves to agree on “the principles of the United Nations”, and announce their intention to form a joint committee to administer the French Empire in the war. The two generals will be the co-chairs. This draft communiqué is submitted to Giraud and de Gaulle. Giraud accepts from the outset; de Gaulle remains to be convinced.

General de Gaulle is in a very bad mood. He has just learned that Roosevelt held the day before to the Sultan of Morocco “a language that did not fit well with the French protectorate”; he also learned that in a meeting with Giraud, Churchill arbitrarily set the value of the pound sterling in North Africa at 250 French francs, instead of the 176 francs previously fixed. It is also said that Churchill and Roosevelt agreed to recognize general Giraud “the right and duty to act as manager of French, military and economic and financial interests.”* To crown it all, de Gaulle has just been informed that the conference ended within twenty-four hours – while at no time was the General informed or consulted about future operations plans…

*Far from endorsing this formula, Churchill did not even see it. When he becomes aware of it at the beginning of February, he will have it substantially amended.

The leader of the France Combattante is still ruminating all these “affronts” when Robert Murphy and Harold Macmillan come to submit to him the draft communiqué established during the night. And de Gaulle wrote in his memoirs: “No doubt the formula was too vague to commit us too much. But it had the triple disadvantage of coming from the Allies, of implying that I was renouncing what was not simply the administration of the Empire, and finally of giving the impression that the entente was realized when it was not. After taking the unanimously negative opinion of my four companions, I replied to the messengers that the expansion of French national power could not result from foreign intervention, however high and friendly it might be. However, I agreed to see the President and the Prime Minister again before the dislocation scheduled for the afternoon.”

Churchill was also in a very bad mood: de Gaulle refused to come to Anfa; when he finally came, he refused to get along with Giraud, then he refused the Anglo-American plan of reconciliation between the French, and now he refuses even to sign a communiqué intended to mitigate the effects of all his refusals! He, His Majesty’s Prime Minister, was literally flouted in the presence of the President of the United States, by a man whom everyone considers his obligated and his creature. The General’s behavior is inexcusable… For Churchill, the fact that de Gaulle may be right is only an aggravating circumstance. The Prime Minister is not only in a bad mood; he is out of his mind.

The farewell visit that the head of Free France will pay to Mr. Churchill will therefore be a very lively one. Churchill preferred not to say anything about it in his memoirs. De Gaulle wrote: “My meeting with Mr. Churchill was, by his own fault, extremely bitter. Of the whole war, it was the harshest of our encounters. In a vehement scene, the Prime Minister addressed bitter reproaches to me, where I could see nothing but the alibi of embarrassment. He told me that on his return to London he would publicly accuse me of having prevented the entente, would set against me the opinion of his country and appeal to that of France.” Churchill added that if de Gaulle did not sign the communiqué, he would “denounce him in the House of Commons and on the radio.” To which de Gaulle replied that “he is free to dishonor himself”. “I confined myself to replying to him,” de Gaulle wrote, “that my friendship for him and my attachment to the English alliance made me deplore the attitude he had taken. To satisfy America at all costs, he espoused a cause that was unacceptable to France, disturbing to Europe, regrettable to England.” On this, de Gaulle goes to visit the President in the neighboring villa…

Meanwhile, Harry Hopkins, after seeing Macmillan, told the President that de Gaulle refused to sign the communiqué. “He was not satisfied with it,” Hopkins wrote, “but I urged him not to disavow de Gaulle, even if he misbehaved. I was convinced – and still am – that Giraud and de Gaulle wanted to work together; I therefore asked the President to be conciliatory and not to mistreat de Gaulle too much. If he needed to be bullied, I told him, let Churchill take care of it, since the Free France movement was financed by the English. I say to the President that, in my opinion, we would be able to get the two generals to agree on a joint statement, and a photo where we would see them together. Giraud arrived at 11:30 am. At that time, de Gaulle was at Churchill’s house. Giraud wanted confirmation of the promises made to him about deliveries to his army, but the President sent him back to Eisenhower. The conference went very well. Giraud agreed to collaborate with de Gaulle. Giraud comes out. De Gaulle and his entourage enter, de Gaulle calm and self-confident – I liked him – but no joint communiqué, and Giraud will have to be under his command. The President expresses his point of view in very energetic terms and strongly urges de Gaulle to come to an agreement with Giraud, in order to win the war and liberate France.”

“The President expressed to me,” de Gaulle wrote, “the sorrow he felt at the fact that the understanding of the French remained uncertain and that he himself had not been able to get me to accept even the text of a communiqué. “In human affairs, he says, you have to offer drama to the public. The news of your meeting with general Giraud, in a conference where I find myself, as well as Churchill, if this news were accompanied by a joint declaration of the French leaders and even if it were only a theoretical agreement, would produce the dramatic effect that must be sought” – “Let me do it, I replied. There will be a statement, although it cannot be yours.”

“At that moment,” Hopkins noted, “the secret service called me on the phone to warn me of Churchill’s arrival. The latter spoke with Giraud from whom he took leave. Churchill came in and I brought Giraud back, convinced that, if the four of them could be reunited, we could reach an agreement. This was happening when it was close to noon, the time when the press conference was to be held. The President was surprised to see Giraud, but he did not let anything appear.”

And de Gaulle continues: “Then came Mr. Churchill, General Giraud and their retinue, finally a host of military leaders and Allied officials. As everyone gathered around the President, Churchill repeated aloud against me his diatribe and threats, with the obvious intention of flattering Roosevelt’s somewhat disappointed self-esteem.”

Robert Murphy, who is also present, will also evoke the diatribe of the Prime Minister: “Churchill, whom the stubbornness of de Gaulle has infuriated, waves his finger in front of the figure of the General. In his inimitable French, his dentures slamming furiously, he shouts: ‘Mon Général, il ne faut pas obstacler la guerre.’”

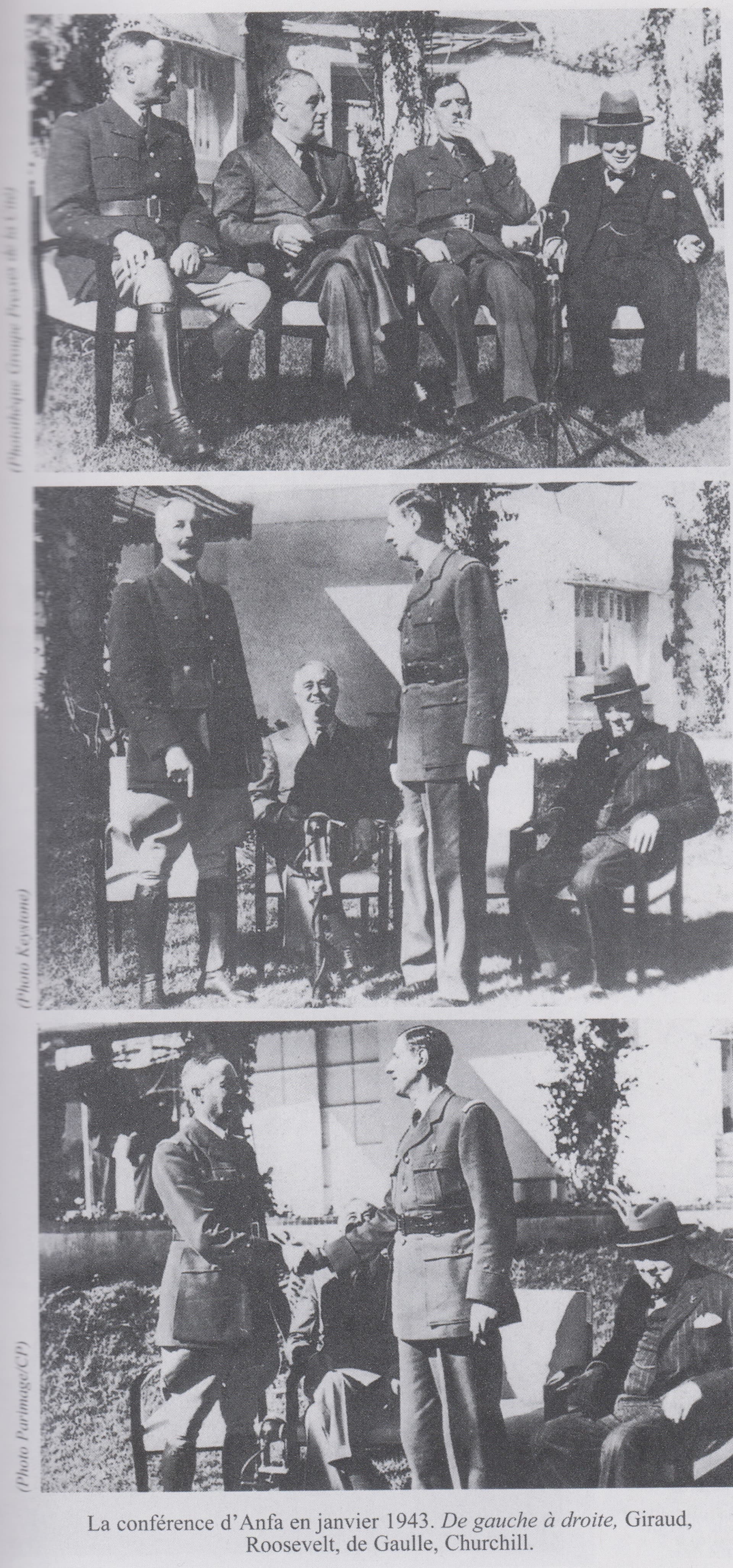

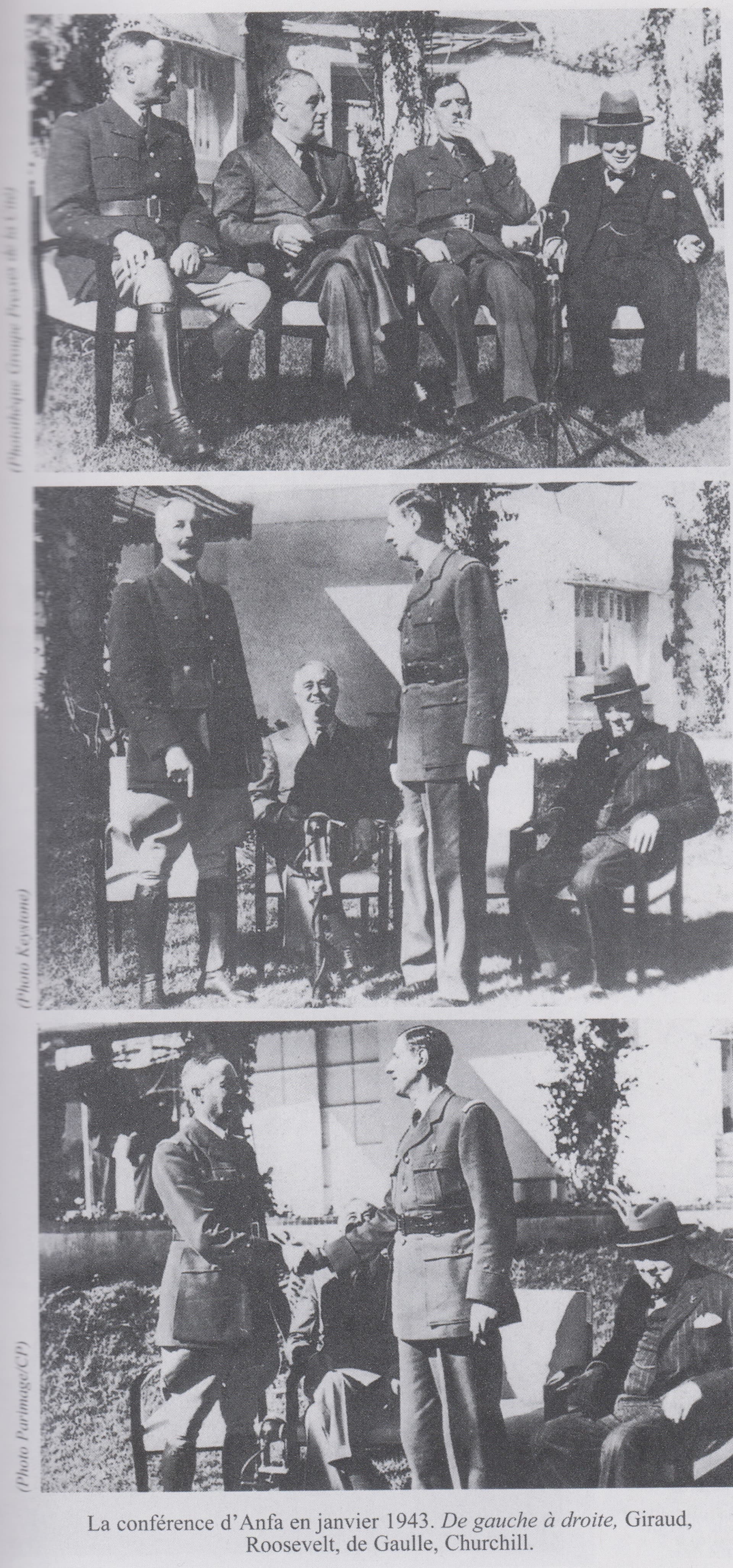

The President, de Gaulle wrote, “felt sorry not to notice him, but, by contrast, adopted the tone of the best grace to present me with the final request that was close to his heart.” Would you accept, at least, he said, to be photographed at my side and alongside the British Prime Minister at the same time as general Giraud?” – “Willingly, I replied, because I have the highest esteem for this great soldier.” – “Would you go,” asked the President, “to the point of shaking hands with general Giraud in our presence and in front of the objective?” My answer was, “I shall do that for you.” Then Mr. Roosevelt, enchanted, was carried into the garden where were in advance, prepared four seats, pointed cameras without number, lined up, pen in hand, several rows of reporters."

And Hopkins notes in his diary: “I don’t know who was more stunned, the photographers or de Gaulle, when the four of them went out, or rather all three, since the President was carried to his chair. I admit that he was a rather solemn group. The cameras began to turn. The President asked de Gaulle and Giraud to shake hands. They got up and executed. Some of the operators could not record the scene, so the generals started again. Then the French and their retinue left. Churchill and the President sat under the hot African sun – thousands of miles from their country – talking to the press correspondents about the conduct of the war.”

It was on this occasion that Roosevelt made his famous statement on “unconditional surrender.” But general de Gaulle has already returned to his villa. Before flying to London, he wrote a statement that began: “We saw each other. We caused…” There is, however, a concrete element: a permanent link will be established between the two generals. Finally, both affirm their faith in the victory of France and in the triumph of “human freedoms”. Despite the unfortunate “Joan of Arc affair”*, de Gaulle returned to London convinced that he had made an impression on the President. Shortly after his return to London, he wrote to general Leclerc: “My conversations with Roosevelt were good. I have the impression that he has discovered what the France Combattante is. This can have great consequences afterwards.” General de Gaulle may be deluding himself here – at least as much as President Roosevelt himself, when he imagines that Anfa’s staging contributed to the solution of the problem of French unity. Indeed, the President seems to have allowed himself to be caught up in the illusion that he himself created, and he thinks he has found a way to maneuver general de Gaulle…

*During their first meeting on January 22, Roosevelt told de Gaulle that he could not recognize him as the sole political leader of France, because he had not been elected by the French people. To which de Gaulle replied that Joan of Arc had derived her legitimacy only from her action, when she had taken up arms against the invader. On the morning of January 24, when Macmillan reported to Roosevelt that de Gaulle had proposed to Giraud to be Foch, while he, de Gaulle, would be Clémenceau, the President exclaimed: “Yesterday he wanted to be Joan of Arc, and now he wants to be Clémenceau…!” Roosevelt then told Hull that de Gaulle had told him: “I am Joan of Arc, I am Clémenceau!”; then he will entrust to the ambassador Bullitt that he said to de Gaulle: “General, you told me the other day that you were Joan of Arc and now you say that you are Clémenceau. Which of the two are you?” To which de Gaulle would have replied: “I am both.” Then, the President will tell that he retorted to de Gaulle: “We must choose; you still can’t be both.” When history reaches the ears of Vice-Consul Kenneth Glow, it was further amplified: “President Roosevelt confided to de Gaulle that France was in such a critical military situation that it needed a general of Napoleon’s caliber.” But I’m that man," de Gaulle replied. “Financially,” the President continues, “France is in such a state that it would also need a Colbert” – “But I am that man,” de Gaulle said modestly. Finally, the President, concealing his astonishment, declares that France is so politically devastated that it would need a Clémenceau. De Gaulle stands up with dignity and says: ‘But I am that man!’" When the press seized on the story, de Gaulle also became Louis XIV, Foch, Bayard, etc. Before leaving Anfa, General de Gaulle will hear some of the first versions. They won’t make him laugh at all…

Churchill, on the other hand, no longer has any illusions about this. If the Anfa conference was a great success for British strategists, it was on the other hand a bitter failure for the Prime Minister; his personal intervention in French affairs ended in a diplomatic rout, the memory of which will remain engraved in his memory for a long time. At the end of the conference, Churchill and Roosevelt went to Marrakech. That evening, during the dinner, the American Vice-Consul Kenneth Pendar inquired about general de Gaulle. “Churchill seemed upset,” Penda writes, “and said to me a typical Churchillian answer: ‘Oh, let’s not talk about that one. We call him Joan of Arc, and we are looking for bishops to burn him.’” But this time again, if Churchill is all to his fury against general de Gaulle, he does not lose sight of the vital interests of France; so, after complaining bitterly about general de Gaulle to the American vice-consul, Churchill turned to Hopkins and said, “Well, Harry, when you go back, make everyone understand that it is important to send weapons here as quickly as possible. This is the only way to strengthen the French.” It is true that Churchill never ceases to evoke France with tears in his eyes, and that he confided to his private doctor two days earlier: “De Gaulle is the soul of this army. It may be the last survivor of a warrior race.”

Basically, Churchill still had the same admiration for de Gaulle; but he also begins to hate him seriously. It is true that the Prime Minister is not resentful, but in this case, he will make an exception. As for de Gaulle, he returned to London “outraged by the way the Prime Minister treated him”. This means that relations between France Combattante and its British ally are likely to be very turbulent during the next few months.