The advance began on the 15th January. Things went well to begin with and by the 19th January we were up against the HomsTarhuna position, which the enemy clearly meant to hold if he could. On the axis of the coast road through Horns the 51st Highland Division seemed to be getting weary, and generally displayed a lack of initiative and ginger. A note in my diary dated the 20th January reads as follows: “Sent for the G.O.C. 51st (Highland) Division and gave him an imperial ‘rocket’; this had an immediate effect.” The leading troops entered Tripoli at 4 a.m. on the 23 rd January 1943, three months to a day since the beginning of the Alamein battle.

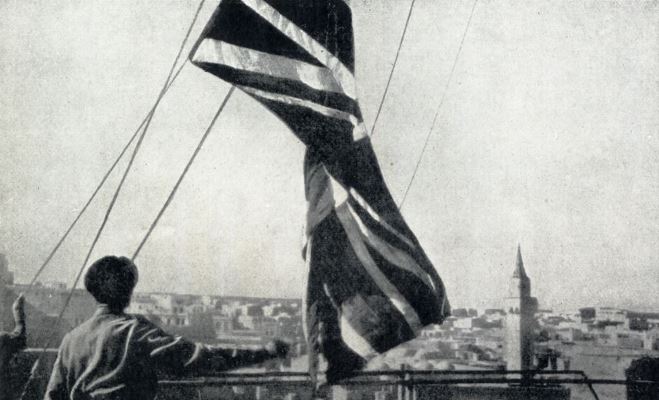

THE EIGHTH ARMY IN TRIPOLI

We had a good reception from the population; the city was quiet and there was no panic. I myself arrived outside the city at 9 a.m. on the 23rd January and sent for the leading Italian officials to come and report to me. I gave them my orders about the city and requested their co-operation in ensuring the well-being of the population. I appointed Brigadier Lush, Deputy Chief Political Officer for Tripolitania, to take over civil control as soon as he could—working through the Italian authorities. I imposed a strict military control for the first 24 hours, so as to establish a good degree of discipline; shops were shut, curfew was imposed at night, and so on.

I foresaw certain dangers in the proximity of my army to a large city like Tripoli. Palaces, villas, flats, were available for officers. I myself was asked if I intended to live in the Governor’s palace. I said “No,” and installed my headquarters in the fields some 4 miles outside the city. Much fighting lay ahead and I was not going to have the Eighth Army getting “soft,” or deteriorating in any way. I forbade the use of houses, buildings, etc., for headquarters and troops; all would live in the fields and in the desert, as we had done for many months. The army had to retain its toughness and efficiency.

Having given orders about these things, I drove into the city with General Leese , 30th Corps commander and we sat in the sun on the sea front and ate our sandwich lunch. We were great friends, and we discussed together the past and the future. Our A.D.C.s and police escort sat not far away, also having their lunch. I asked Leese what he thought they were talking about after many months of monastic life in the desert; he reckoned they were speculating on whether there were any suitable ladies in the city. I had no doubt that he was right. I decided to get the Army away from Tripoli as early as possible.

Two days after we arrived in the city it was reported to me that the food situation was deteriorating among the civil population. I at once issued the following order:

*“1. The food situation in Tripoli is not good; the civil population is likely to be short of food very shortly, and then would have to be fed by the Army. This would be a commitment which would cause us serious embarrassment; it would therefore be exactly what the Germans would like to happen. *

*2. The British Army, the Allied Air Forces, and the personnel of the Royal Navy in Tripoli, have their own rations and must not eat the food of the civil population. The enemy would make very good propaganda out of the fact that enough food was left by them and a good deal of it was eaten by the British forces. *

*3. It is therefore my order that no member of the British forces in Tripolitania, whether officer or other rank, shall have any food—breakfast, lunch, dinner or supper—at hotels or restaurants in Tripoli. *

4. The only exception to this order will be that tea shops may, if they are able and willing, sell tea and buns to the troops."

*5. Officers and other ranks visiting Tripoli must take their rations with them. Arrangements are being made to establish clubs for officers and other ranks in Tripoli which will be run by the N.A.A.F.I., and these will be opened as soon as possible; it will not be possible to provide meals at these clubs, except possibly tea and buns. *

6. Commanders will ensure that the terms of my order in para. 3 above are brought to the notice of all officers and other ranks, together with the reasons for it. The D.C.P.O. will ensure that hotel and restaurant managers receive orders not to serve meals to personnel of the British forces.”

The Prime Minister and the C.I.G.S. visited Tripoli on the 3rd and 4th February and we organised for them parades of the Highland Division and the New Zealand Division, with certain units of the Royal Armoured Corps and the R.A.S.C.

Winston Churchill was immensely impressed, and was deeply moved when the troops marched past him: looking so fit and well, and with such a fine bearing. I felt a very proud man myself, to be in command of such men.

I asked him to address the officers and men of my headquarters, and it was then that he said: “Ever since your victory at Alamein, you have nightly pitched your moving tents a day’s march nearer home. In days to come when people ask you what you did in the Second World War, it will be enough to say: I marched with the Eighth Army.”

After getting to Tripoli on the 23rd January my main preoccupation was to get the harbour uncorked and ships inside, so as to get a good daily tonnage landed. This was the task of the Royal Navy, and no easy one to do quickly. Speed was vital; my chief engineer went to work with the Navy, and we helped with all our own resources. This made a great difference; the first ship entered the harbour on the 3rd February and the first convoy on the 9th February. I was anxious to do away with the road link from Tobruk and Benghazi as soon as possible, abolish the “Carter Paterson” service, and maintain Eighth Army from the Tripoli base.

The next tough battle would be on the Mareth Line; this was a very strong position and the main feature of the attack upon it would have to be an outflanking movement round its western flank. I envisaged using the New Zealanders on this task and I had launched reconnaissances before Christmas, when we captured the Agheila position, i.e. nearly three months before the Battle of Mareth took place.

Meanwhile our first task must be to push the enemy back on to the main position so that we could reconnoitre it. We also needed to secure the necessary road centres of communication at Ben Gardane, Foum Tatahouine and Medenine, and the lateral roads, and the airfields about Medenine. But as our administrative situation eased so I began to build up strength in the forward area, sending up the 51st (H) Division and a further brigade of tanks.

Towards the end of February the port of Tripoli was working well and we were discharging up to 3500 tons a day. My administrative anxieties were over and I could bring 10 Corps forward to Tripoli from the Tobruk-Benghazi area.

I must mention that General Leclerc had joined me, having come up from central Africa with his small French force. He put himself under my command. All he asked in return was that I should give him food, petrol and clothing: which I did, as I was glad to get the help of this remarkable man.

In accordance with decisions taken at the Casablanca Conference, which had assembled in January, the Eighth Army was to come under General Eisenhower for the fighting in Tunisia; Alexander was made Deputy C.-in-C. and was to command the land forces. Tedder became C.-in-C. of all air forces in the Mediterranean theatre. This grouping was good, and if we played our cards properly the successful outcome of the operations in Tunisia was certain. The air power in Tunisia, in Malta, and with the Eighth Army could now be concentrated and the whole of it used to support any one operation.

Coningham went over to join Tedder as commander of the Tactical Air Forces, and Harry Broadhurst took command of the Desert Air Force working with the Eighth Army.

Alexander told me he had found things in a terrible mess when he went over to join General Eisenhower. The First Army was being heavily attacked on the southern part of its front and everything looked like sliding there. Generally, he found stagnation: no policy, no plan, the front all mixed up, no reserves, no training anywhere, no building up for the future, so-called reinforcement camps in a disgraceful state, and so on. He found the American troops disappointing; they were mentally and physically soft, and very “green.” It was the old story: lack of proper training allied to no experience of war, and linked with too high a standard of living. They were going through their early days, just as we had had to go through ours. We had been at war a long time and our mistakes lay mostly behind us.

Alexander worked day and night to get things right. But he had some anxious moments and he sent me a very real cry for help on the 20th February, asking if I could do anything to relieve the pressure on the Americans. I replied that I would do all I could—adding that if he and I exerted pressure at the right moments we might get Rommel running about like a “wet hen” between our respective fronts. My staff always used to refer to this message as the “wet hen” signal!

I speeded up events and by the 26th February it was clear that our pressure had caused Rommel to break off his attack against the Americans. This gave Alexander the time he needed, and he wrote to me on the 5th March saying that he reckoned the patient had passed the crisis and was on the way to recovery; but the military body is always left with great weakness after such an illness. When the Americans had learnt their lesson, and had gained in experience, they proved themselves to be first-class troops. It took time; but they did it more quickly than we did.