Longstop Hill

WHAT A legend Longstop had become. We checked it on a dozen different maps. We explored the roads and tracks around the hill. We talked about it: ‘Once we are on Longstop. . .’ The veterans who had mounted the hill before we were thrown off in the early days declared that on a clear afternoon you could almost see Tunis from the heights.

In the German ranks too, Longstop was a great thing. When an officer of the Panzer grenadiers was taken prisoner he declared, ‘You will never take Longstop. It is impregnable now.’

For five months it had lain right in the front line, the fortress of the Medjerda Valley, the locked gate on the road to Tunis. We climbed the surrounding hills and looked down upon the hill and it always appeared darker than the surrounding country and more sinister, a great two-humped bulk that heaved itself out of the wheat fields like some fabulous whale beached on the edge of a green sea.

All through April the Seventy-Eighth British Division had been edging its way along the heights toward Longs top. One after another the mountain peaks had been cleaned out. Toukabeur village and Chaouach had fallen, and while the donkeys and the mule teams dragged up ammunition and food the men crept forward on to Jebel Ang. At last, on April 22nd, the men in the forward platoons could look right into the German defences of Longstop itself.

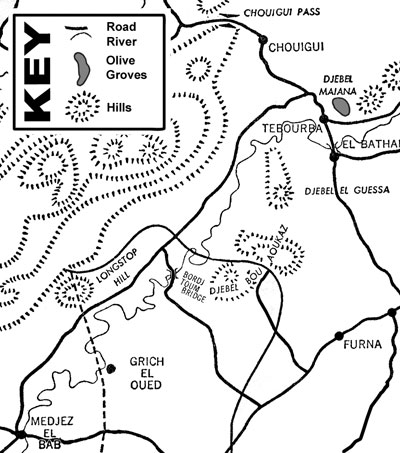

Longstop map

To launch his final assault General Eveleigh, commanding the Seventy-Eighth Division established his headquarters high up in the mountains and very close to his operational brigades. To get to this place you had to turn off the main road just short of Medjez-el-Bab and take a winding earthen track through Toukabeur. The track began in a field of poppies that spread in a blood-red pool across the floor of the valley; it finished in miraculous alpine fields where a flower of the most delicate lavender bloomed among the rocks.

We called on the Intelligence major we knew best. ‘It’s started,’ he said. ‘You can have a look at it if you go round that corner. Don’t go on to the top of this hill because there’s a lot of red flannel up there.’

‘A lot of red flannel’ presumably meant General Alexander and his staff, who usually wore their red bands at the front, had come to watch the battle; so we took a lower track and moved through the stunted mountain trees looking for a good commanding point. The British twenty- five-pounders were making vicious cracking echoes through the rocks. Heaven knew how the guns had been dragged to those heights. Beyond the last battery we crept around the crest of a steep hill until we were in view of the enemy in Heidous village across the valley and Longstop lay below us on the right.

From that height everything appeared to happen in miniature. The Churchill tanks climbing on Jebel Ang looked like toys. The infantry that crept across the uplands toward Heidous were tiny dark dots, and when the mortar shells fell among them it was like drops of rain on a muddy puddle. Toy donkeys toiled up the tracks toward the mountain crests, and the Germans, too, were like toys, little animated figures that occasionally got up and ran or bobbed up out of holes in the ground between the shell explosions.

Most of our shells were falling on the near slopes of Longstop. The barrage kept rushing over our heads and falling among the black gorse on the hill, and at times it was so heavy everything disappeared in grey-black smoke and the hill became a cloud of fumes and dust.

On Longstop the Germans had dug trenches which had a horizontal shelf deep below the surface. During a barrage such as this the Germans lay under this shelf and waited in safety. Their guns were fired from below the surface so that it was only in the very last stages of an assault that they had to put their heads out. They had ample stores of food and water and ammunition. The Germans knew that the British infantry would have to cross the minefields first and that they would have to expose themselves as they climbed upward. It was no use our ignoring Longstop by going round it. The Germans would still be able to shell the two roads running into Tunis. They would break up our convoys. They would launch counterattacks from the hill. And so it was necessary now, even at great cost, for the Seventy-Eighth Division to make a direct assault.

On the second morning of the battle, when the British guns had done all they could, I went with my party down onto the plain before Longstop to see the infantry go in. The brigade in charge of this operation had taken over a farmhouse in a little grove of trees. The command vehicles were drawn up against a wall close to a ruined tennis court.

The enemy seemed to be aware that this was a headquarters because they kept firing at the place, occasionally with 88-millimetre shells, occasionally with mortars that sent up puffs of black or white dust according to whether they landed on rock or soil. It was never quite clear until the last second whether shells would fall over the farmhouse or short of it. As we came up the road a padre said to us, ‘It is very difficult at the moment. I have been trying to get to some of our dead, but every time I go out they can see me and they start mortaring. I shall have to wait until it is dark.’ The padres were very brave on this front, and some had been decorated for it. They were armed only with their helmets and their faith, and often they went forward with the attacking infantry to be at hand to help with the wounded. At these times they did not pray or preach on the battlefield: they dealt out brandy to the dying and administered morphia and helped bind the wounded and get them back in trucks and Bren-gun carriers to the dressing stations. They carried food and water and medical supplies. In return for this the men looked on the padres with an affection and respect which they had never felt at home.

We could see the lower slopes of Longstop quite clearly from brigade headquarters, and even here, only half a mile off, the hill looked dark and uncouth. Zero hour for the attack was 1.30 p.m., but the Germans above could see our infantry massing, and they were already firing very heavily upon them with mortars. The West Kents, the Surreys and the Argylls were making this attack, each taking a separate part of the hill, and they had a few Churchill tanks in support as well as the artillery that kept banging away at the places where the German mortars seemed to be hidden.

At one o’clock the artillery increased, and for the fiftieth time the hill disappeared in dust. At 1.20 the guns fell silent. There was a long pause. The shell-dust lifted slowly off the hill. At 1.30 a flare rose out of the foothills and at that signal the attack was on. In little quick ripples of noise the machine-guns sounded first from one side of the hill then the other. Sometimes the bursts went on as long as a full minute, and always the machine-gunning would be drowned eventually in the crump of the enemy mortars. The mortars fell in sprays of half a dozen or more, and, watching from behind a cactus hedge at the farmhouse, you would see roughly from the mortar-fire how far our men had advanced. At 2 p.m. little dark figures appeared spasmodically on the skyline at the crest of the first slope. They stood silhouetted for a second and then dropped away. Near the top there was a patch of yellow open rock. Men were running across this, always going upward. Then they disappeared for a moment until they were on the skyline and dropping down over the other side.

In a calm, reasonable voice the brigade major was calling over the telephone for a bombing raid to help the advance. His phone was ringing all the time now. Little scraps of coded information were coming back from the battalion headquarters. They were map references, jumbles of figures. You could not tell from the faces of the officers whether the attack was going well or not, but it was obvious that we were advancing.

It was hot, and presently through the dust Bren-gun carriers came rattling down the track that led from the hill. The wounded were piled on the carriers just as they had been lifted there in the midst of the firing. They lay quite still on their backs, staring upwards, and the blood dropped down among the instruments inside the carriers. The drivers sat fixedly in their seats and said nothing. They brought the vehicles to a standstill beside a line of ambulances sheltering under the cactus hedge, and the stretcher-bearers lifted the wounded onto stretchers and slid them into the ambulances. Then the Bren-gun carriers turned and went back through the dust into the battle again.

One of the officers who came back took his helmet off and let it drop on the ground. ‘The men are very tired,’ he said. ‘It’s not the opposition so much, it’s sleep. They have been going for a long time now.’

‘How long?’

‘I don’t know—a long time.’

The officer himself was very tired. He had been in the line for a week, and during the previous night some of his men had just fallen on the ground and cried. They cried because they had no strength any more, not even the strength to stand up. They had continued without sleep for two days under the compulsion of their brains and beyond the point where the body will normally function. But now, when their minds would not work any more, they discovered that the strength had already gone out of their bodies and that, in fact, they had no control of anything any more, not even of tears. The tears came quite involuntarily and without any sense of relief because the body was incapable of feeling anything any more, and what became of the body now was of no consequence. And so they had lain about the hill for an hour or two in a stupor. The cold and the dew bit into them through the night and brought them back to consciousness. Then they had stumbled about in the darkness until they found their platoons. They ate a little cold bully without tasting it and took swigs from their water bottles. By morning their brains were operating again, not their bodies, but their brains, and they were able to contemplate themselves and consider what still had to be done. Some of them slept in the sun through the morning and this brought back a little strength into their bodies—enough to cooperate with their minds and give obedience. At noon then, they had regrouped, and they mechanically registered the order that they had to attack again, and they assessed their strength against what was required by the order. These were the men we had seen running across the top of the slope and the men who came back in the Bren-gun carriers.

The wounded were not just yet in great pain because the shock of the bullets in their flesh was still taking effect. They were very dirty, and the dirt ran in lines in the sagging hollows of their faces. Their hands dropped over the edges of the stretchers, lumpish hands, coloured a greyish yellow colour that was inhuman. No one could look at them without protesting.

The German prisoners came next. Black jackboots, green gabardine uniforms, wings on their chests, cloth caps with the red, white and black badge, the Afrika Korps. They marched stolidly in columns of three, the officers in front. They were not so tired as our men, since they had been lying in provisioned dugouts, and they marched mechanically, but well. One of the officers started to argue. He wanted to see a British officer. A Scots sergeant waved him on bleakly with the tip of his bayonet.

The Germans stood stolidly beside the ambulances, waiting their turn to go into the cowshed. In the cowshed British military police were running their hands over each prisoner, taking away from him his combined knife, fork, spoon and tin-opener, a neat gadget, also his pocketknife and any weapons he carried. The Germans submitted to this, automatically raising their hands above their heads. The pile of knives and forks got larger and larger on the floor. Some of the Germans started smoking after the search; and they sat quietly on a fallen log. There was something in their faces that registered not fright or fear, but deep tiredness, a sense of relief. Only the German officer was still arguing. A British captain who had been tending the wounded came over to him.

‘You bastard,’ he said. ‘Get back in your place.’ The German, not understanding, offered the British officer a cigarette.

The British officer said again, ‘Get back.’ It was quite clear that, having come so recently from the fighting and the wounded, he wanted to shoot the German.

There were many scenes like this that day. The Germans were firing their machine-guns until the British got within thirty yards or so—near enough to kill. And then the Germans surrendered. This meant that we were taking many casualties but not killing many Germans, and the physical presence of the prisoners did not entirely satisfy the desire of the British troops for revenge.

Longstop Hill battle depiction and aftermath

That night they took three-quarters of Longstop Hill. As soon as it was light in the morning I drove to brigade headquarters. A young signals officer was going up to the hill in his truck and he offered to take my party with him. We got only half a mile in the truck and then, leaving it under the cover of the high wheat, we began climbing on foot, keeping to the right-hand side of the hill. We followed the line of the signal wires so that we could check for breakages. Every few yards the wheat had been torn up and blackened as though some sort of plague had blighted it; this was the effect of the mortars, which were fused so that they exploded immediately on contact and were therefore more likely to kill men. It was very hot. The dust rose up out of the wheat, and when it had coated one’s face and body little runnels of sweat ran over one’s cheeks and under the armpits.

Now we were on the hill, I saw that it was much more thickly covered with scrub than had appeared from the distance; and it did not consist of two big humps, but a whole series, seven in all, with many subsidiary ridges. As soon as we pulled ourselves to the top of one slope another appeared above us. Over all this ground the troops had fought the day before, and now the carriers were bringing up water cans that had to be lugged the last half of the journey by hand.

On the lip of the third rise we came suddenly upon a scene so dramatic, so complete in itself that I recall it now, detail by detail almost as I would remember a painting or a play in the theatre. It was a front-line trench. The Germans had dug it, but our men had occupied it the day before. It was a shallow trench and it made a zigzag suture through the blackened grass on the slope of the hill. On the piles of freshly turned yellow soil the men had thrown their battledress jackets, the tin mugs and plates from which they had been eating, the empty salmon and bully-beef tins.

A profusion of things lay about all the way up the trench—empty packets of cigarettes, both British and German, water bottles and hand grenaders, half-used boxes of cartridges, German steel helmets, bits of notepaper, discarded packs and torn pieces of clothing. Through this mess the rifles and machine-guns were pointing out toward the next slope, but the men were not firing. The sun was shining strongly and they sat or leaned half in and half out of the trench. Some smoked. One man was mending a boot. Another was sewing on a button. But mostly they leaned loosely on the earth and rested. Every time an enemy gun sounded they cocked their heads mechanically and waited for the whine that would give the direction of the shot. It was only a slight movement and you did not notice them doing it at first. Sometimes the shells landed short, three or four hundred yards away, sometimes very near, perhaps only fifty yards down the slope, but anyway not on the trench. No one commented on the nearness of the shells. They had had much heavier shelling than this all night, and these spasmodic shots were only a nuisance that still had the power to hurt unless one watched.

There were several old London papers lying about. One, the Daily Mirror, had its last page turned upward and its thick headline read: ‘ “No more wars after this,” says Eden.’

Seeing me looking at it, the soldier on the end of the trench said bitterly, ‘They said the last war was going to end all wars. I reckon this war is supposed to start them all again.’ The others in the trench laughed shortly and one or two of them made some retort. The men had greeted us with interest, but without enthusiasm. When they read the war correspondent badges on our shoulders they were full of questions and derisive comments. ‘Why weren’t you up here yesterday? You’d have seen something!’ Then another, ‘You can tell Winston Churchill we have been in the bloody line ten bloody weeks already.’ Then a third, ‘Are you the bastard that wrote in the paper that we’re getting poached eggs for breakfast every morning?’ And a fourth, ‘Where’s the Eighth Army? Aren’t they doing anything?’ And several of them, ‘How’s the war going, mister? Is there anyone doing anything besides us?’

They were hostile, bitter and contemptuous. Every second word was an adjective I have not quoted here, and they repeated it ad nauseam. They felt they were a minority that was being ordered to die (a third of them had been killed or wounded in the night) so that a civilian majority could sit back at home and enjoy life.

It was useless to picture these men who were winning the war for you as immaculate and shining young heroes agog with enthusiasm for the Cause. They had seen too much dirt and filth for that. They hated the war. They knew it. And they were very realistic indeed about it. Instead of sitting on an exposed hilltop in the imminent danger of death they would have much preferred to have been on a drunk, or in bed with a girl, or eating a steak, or going to the movies. They fought because they were part of a system, part of a team. It was something they were obliged to do, and now that they were in it they had a technical interest and a pride in it. They wanted to win and get out of it—the sooner the better. They had no high notions of glory. A great number of people at home who referred emotionally to ‘Our Boys’ would have been shocked and horrified if they had known just how the boys were thinking and behaving. They would have regarded them as young hooligans. And this was because the real degrading nature of war was not understood by the public at home, and it never can be understood by anyone who has not spent months in the trenches or in the air or at sea. More than half the army did not know what it was because they had not been in the trenches. Only a tiny proportion, one-fifth of the race perhaps, know what it is, and it is an experience that sets them apart from other people. If you find the men do not want to talk about the fighting or what they have done, it will be for this reason only—they want to forget it.

We went higher onto Longstop to join the Argylls, and as we moved off, the men shouted at us to keep down so that we would not draw the fire onto their position.

The Argylls, too, were resting after the bad night, and their eyes were red-rimmed with fatigue. The commanding officer had been killed. His deputy, a tall major who was a Highland farmer, had been drinking wine with us at Thibar only a few days before, but now a great gulf of experience separated us. He was still as hospitable and level-headed and kind, but there was something he could not communicate. We were very near the top of Longstop here. From the surrounding caves Germans were still being routed out. We overlooked a German gun-pit, empty now of men, but the black snouts of the guns still pointed toward us. In every direction the rocks were chipped with shell-blast and the camel thorn was rooted from the ground. A light heat haze hung over the far end of the hill, where the Germans were still hiding and shooting.

Below us the Medjerda Valley spread out majestically, and we looked for miles across the enemy lines and deep into our own. At that moment, surprisingly, half a dozen enemy shells whistled over our heads and landed on the brigade headquarters we had just left at the bottom of the hill. The cowshed, where the prisoners were, was enveloped in great billows of smoke, and all that part where the ambulances lay appeared to be in the range of fire. There had been so much killing all around here that the only emotion I felt was: ‘I’m glad I’m not still in the cowshed.’

It was a shock, then, to look across the valley and see that an entirely separate battle was going on. Longstop had for the past forty-eight hours so absorbed our interest that we had begun to think that it was the whole battle. But now I remembered Alexander had sent two armoured divisions into the Goubellat Plain, and other formations were working up from Medjez-el-Bab to the villages of Crich-el-oued and Sidi Abdallah in the centre and southern side of the valley. Tanks were moving about very briskly and firing, but from that distance we could not see exactly what they were doing. Bombers kept coming in low and adding to the turmoil on the plain. Crich-el-oued (inevitably the troops called it Cricklewood) was having an especially rough time, and it was surprising to see the minaret of its little mosque survive the constant salvoes.

As we watched, another officer of the Argylls came up, a major named John Anderson. Just before he introduced us our friend whispered, ‘Here’s the man who did the whole thing. Don’t say anything about it, but we have put him in for the V.C.’

It was not much good asking Anderson how Longstop had fallen. ‘Oh, I don’t know,’ he said vaguely. ‘I shouted “Come on!” and the boys jumped up and ran forward shouting at the tops of their voices. We found the Germans cowering in their trenches—it was probably the noise that made the Jerries give in.’

Anderson, to look at, was not very different from the other officers in this battalion except he was still alive and most of the others were dead or wounded. He himself had been slightly wounded. His uniform was in a bad mess and his beard was matted with sweat and dirt. What he had done was this. He had led the frontal attack at night up the first slope. With so much fire coming from every direction and so many confusing explosions and flares, the only thing that was clear was that the enemy was somewhere above. Anderson, armed with a revolver, did the thing that sounds so mundane in words. He stood up in the fire and shouted to his men. They swarmed up after him as men will when they find a leader. He ran straight through the minefield and up through the darkness to the points where the yellow streams of bullets were coming out. He and his men yelled and screamed as they flung themselves upward. They got caught in barbed wire and clawed it aside. Some were shot down. The others jumped down into the dugouts on top of the Germans, firing as they jumped. That was one hill. There were still men left, and Anderson jumped up again. Sheer rage carried them up the next slope, and again they broke through the wire and killed with the bayonet. Even then there were a few of the Argylls left who had not died or been wounded, and a third time Anderson ran on and upward until he had achieved this height.

Many such things happened on Longstop during this terrible three-day battle, but this was one of the great charges. When the third day came it was evident that the enemy defences were pierced, and as we stood near the summit that afternoon new units were going in to mop up the rest. Longstop was taken in the only possible way, by men going in yelling with the bayonet and meeting the enemy face to face.

Anderson got his V.C. and died fighting in Italy six months later.