DISCLAIMER: The vast majority of this information is either directly quoted from the sources below or only slightly changed. Very little of it is my original thoughts, save a paragraph here or there. I attribute the following completely to my sources and make no claims otherwise. If so desired I will remove this content from the website without hesitation if asked to do so by TIMEGHOST or by any of the original copyright holders. My intent is purely the sharing of historical knowledge regarding Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic.

Sources:

“The Far Distant Ships” by Joseph Schull, ISBN-10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

“North Atlantic Run” by Marc Milner, ISBN-10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Joseph Schull’s work, published 1985)

“Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War: Volumes 1 & 2” ISBN-10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

“The Corvette Navy” by James B. Lamb, ISBN 0-7737-3225-X, (A shorter book that contains personal anecdotes of Mr Lamb’s service aboard corvettes during the Battle of the Atlantic, and later his involvement in the D-day landings)

Pictures are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Library and Archives Canada, Uboat.net, The Rooms Provincial Photo Archive, and other sources. I only use photos that exist in the Public Domain unless otherwise stated.

Lost in the Fog, Ineptitude and Bureaucracy, Japan, The End of 1941

Back to the Atlantic, the deficiencies of Canadian sailors were ever-present. The British SOE of convoy SC-45 included a strong criticism of his Canadian escorts in his report of proceedings. Again Canadians were sloppy in signalling and reckless in their use of signal lamps by night. His conclusion, that ‘their convoy discipline is not good,’ was something of an understatement. In action and out of it, the RCN’s expansion fleet displayed an alarming propensity for ineptitude. In fairness, the escorts themselves were hardly to blame for most of this. The example of Shediac’s losing her convoy following an emergency turn and then searching for five days to no avail in an attempt to relocate it made professional naval officers hair turn grey. In the case of Shediac’s misadventure, which happened in mid-October while she was escorting SC-48, no one thought to pass the alteration (arranged by flag while it was still light) directly to her. Shediac having no telescope with which to read flags, had a hopeless task, and the convoy simply sailed off the other way after dark. Rendezvous points with the convoy were unknown to Shediac for some inexplicable reason, and her wireless set was improperly tuned, so that transmissions were not received. HMCS Rosthern went looking for Shediac and became lost herself, as did HMCS Camrose when ordered to do the same. Somewhat to their credit, both ships would encounter merchant vessels that had fallen behind the main group and escort them instead, Camrose finding the merchant vessel of the Convoy Commodore himself, who had dropped out due to mechanical breakdown. Nevertheless, no group of warships ever sailed so ill prepared for the most rudimentary tasks (Save perhaps the Imperial Russian Second Pacific Squadron in 1905). When news of Shediac’s sojourn reached the Staff at Western Approaches, it was treated as more of the same. Admiral Sir Percy Noble, CiC, WA, minuted a bemused ‘no action’ on the report, while an unknown hand summed up the whole affair in five words: ‘A sad states of affairs.’

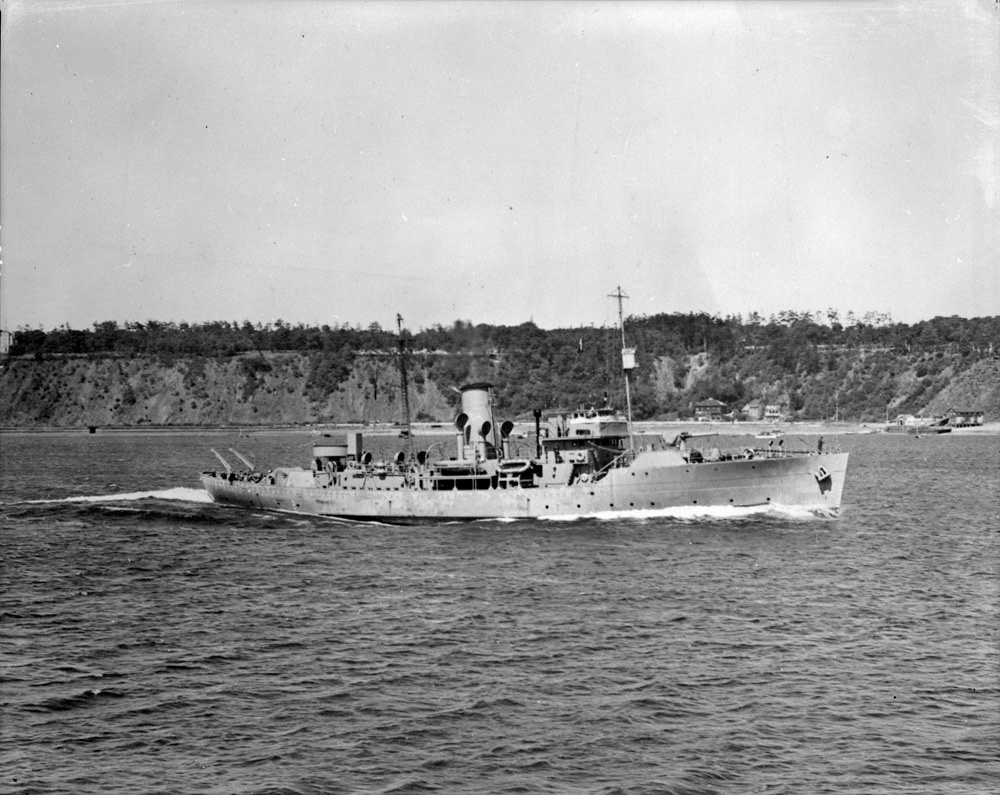

(HMCS Shediac, date unknown)

Losses continued to befall Canadian escorted convoys through October and November, and the prospects for the future looked grim. Shediac’s convoy, SC-48, lost three ships in two separate attacks while the convoy and the escort struggled to recover from a gale-forced dispersal. Reinforcement, in the form of five British and American destroyers and one RN corvette, arrived the next day, but even this enlarged escort could not prevent the loss of six more ships- which spoke volumes for the need to have properly coordinated teams defending convoys. In addition to merchant ship losses from SC-48, one RN destroyer, HMS Broadwater, and the corvette HMS Gladiolus were sunk and the USS Kearny was torpedoed in the fierce battle which surged around the convoy.

Note: The battle of SC-48 would see the involvement of HMCS Baddeck, our old friend Alan Easton from back in Part 1 commanding.

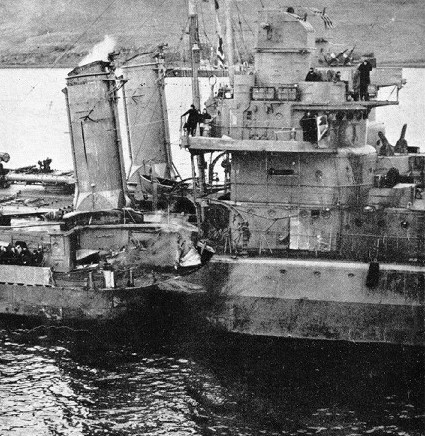

(USS Kearny after making it safely to Iceland with the aid of USS Monssen [right]. The damage she suffered escorting SC-48 is visible on the starboard side. U-568 fired on her after she had repeatedly disrupted the U-boats attempts to get in position to fire a spread at the merchant vessels. Kearny would return to service).

(The damage is fully visible here. Eleven men were killed in this attack. Both photos taken on the 19th of October, 1941. Both photos credit to the US Naval Historical Center)

Through October the packs moved further westwards, and by the end of the month the Germans had concentrated twenty U-boats off Newfoundland in an attempt to intercept convoys as they funneled around the islands. Group ‘Mordbrenner,’ of four U-boats, arrived on station off the Strait of Belle Isle on the 16th of OCtober and was soon joined by ‘Reisswolf’ and 'Schlagetod," both of which had pursued westbound convoys into Newfoundland waters. On the 1st of November, as Mordbrenner moved south to support attempts by Reisswolf to press home attacks on an American-escorted convoy, U-374 sighted SC-52 fifty miles off Cape Race. Operations against ON convoys were immediately dropped and the available U-boats (regrouped now as ‘Raubritter’) sent to attack SC-52. Routing authorities, fully aware from special intelligence of the U-boat dispositions, altered the convoy’s course to due north, while the German attack was hampered by poor radio conditions. Fearing heavy losses in a thousand-mile running battle, the British ordered SC-52 to return to Canada. Before it cleared the danger area, four ships were sunk by Raubritter, and a further two ran aground in fog when the convoy passed through the Straits of Belle Isle. Escorted by a scratch team of two RN destroyers, and five Canadian, one British, and one Free French corvette, SC-52 was the only transatlantic convoy driven back by U-boats alone during the entire war.

The problem of strengthening close escort groups or providing them with rapid reinforcement was a vexing one in 1941. This was particularly so for the RCN, which had limited resources and was bound, under the terms of the Anglo-American accord of August, only to provide escorts, not to manage the campaign. ANy large-scale redistribution of escorts within NEF would have required at least the tacit consent of both the RN and the USN- though the RCN had every right to act in its own interest. Within this rather circumscribed adherence to gentlemen’s agreements, the RC did have some limited options and was never short of ideas. One of them, Lieutenant Commander H.S.Rayner, CO of destroyer St Laurent, advocated using NEF’s destroyers to form five ‘hunting groups’ of four destroyers each to prowl the Newfoundland-to-Iceland route. With two such groups constantly at sea, Rayner believed that reinforcement on an effective scale would be readily at hand for any threatened convoy. The concept was not new, and American help in the Western Atlantic had given the RN sufficient slack to establish a number of these in UK waters. But Rayner’s suggestion would have left the actual escort work to corvettes alone and tinkered with an embryonic group system. Corvettes were considered unsuitable to act as SOE’s ships, while the heresy of tampering with existing groups was obvious, and Rayner’s plan was rejected. Conceivably, the ineffectiveness of massive destroyer support for SC-48 was still fresh in everyone’s minds.

The alternative of actually merging the USN’s destroyer forces with NEF to provide a more equitable distribution of these effective escorts was considered, but never very seriously. Admiral King, as already noted, was opposed to such an idea, as were senior officers of the RCN. Working with European navies-in-exile never presented a problem because they adopted British tactical doctrine and procedure. But the USN was the odd man out in the North Atlantic. Captain (D), Newfoundland replied negatively to just such a proposal in December, stating that amalgamation of the USN and RCN escort forces was ‘inherently inefficient’. The truncated battle of SC-52 in early November was watched closely in St John’s by RCN officers who were concerned about the effects that inefficiency was having on operations. Although the retreat and dispersal of the convoy was not one of the major defeats of the battle of the Atlantic, it was a signal setback for NEF. It showed clearly that the ability of Canadian escorts to push trade safely through to MOMP was seriously doubted by senior operational authorities, both British and American.

Concern among professional RCN officers manifested itself immediately in the form of a strongly worded memo to Captain (D), submitted on the 4th of November, the day after SC-52 altered course to return. The memo began by noting the rough handling recently meted out to Canadian escorted convoys in the Western Atlantic. It expressed doubt about the future os slow convoys and even suggested that they might have to be abandoned. If senior authorities planned to continue with slow convoys, the memo advised, certain steps had to be taken to bolster the expansion fleet’s lamentable lack of ASW fundamentals. It was painfully clear that most corvette captains knew precious little of the basic principles of convoying or of ASW. Their ignorance stemmed not from an unwillingness to learn but rather from the failure of the training system in Halifax.

Most important was the lack of emphasis on coordination and teamwork, essential qualities of effective defence. The RCN’s manning policy was attacked, as were increased sea time and poor training facilities. Time, the memo admitted, was the crucial element: ‘RCN Corvettes… have been given so little chance of become efficient that they are almost more of a liability that an asset to an escort group.’ The memo was signed by Prentice but carried the endorsement of Hibbard, Acting Commander H. Pullen, CO of Ottawa, and Lt. Commander G. Windeyer, CO of Wetaskiwin.

(HMCS Agassiz in St John’s harbour, circa 1942).

Stevens concurred fully with the complaints in the memo, which he forwarded directly to Murray. In his covering letter Captain (D) advised that ‘written reports from other COs have not been called for. It is known they are substantially in agreement.’ Murray must have read the letter and the memo with concern. The situation in his command was now a source of considerable embarrassment to Canada’s professional naval officers. Yet almost certainly he read it with satisfaction. Here at last was written proof from responsible men at sea that the policies adopted by the Naval Staff in Ottawa were adversely affecting NEF and the image of the service. Murray was particularly exasperated by the navy’s manning policy, over which he had no control. Escorts sent from St John’s to Halifax for repairs, common since dockyard space and time were at a premium in Newfoundland, returned to NEF with crews largely composed of new drafts. Yet, aside from being allowed time to store and raise steam, these ships were given no opportunity to integrate and work up the new men.

Ships which one month were at least passably competent were reduced the next to the state of newly commissioned vessels and sent immediately back into operations. This Jekyll and Hyde character of the early expansion fleet must have been particularly baffling to RN officers. Murray was well aware of the problem from very early on and had complained of it in August. In October he bitterly attack Commodore G.C. Jones, the commanding officer, Atlantic Coast, and the manning officers at Halifax for condoning the manning policy. The latter he labelled ‘pirates’ and castigated for lacking the ‘breadth of vision to see that the RCN’s reputation in this war depends on the success or failure of NEF.’ But clearly no action had been taken by November, so Murray, armed with Prentice’s memo, appealed directly to the Naval Staff. In measured tones he condemned the manning policy for undermining the effectiveness of his command, endangering the lives of seamen, and ruining the reputation of the service. On four pages of foolscap paper, closel typed, Murray recounted the litany of efficient escorts reduced to incompetence as a result of visiting Halifax. One of the more damnable effects of this policy was that it worked the few good people who were available into near exhaustion.

Lieutenant Brigg’s Orillia, for example, had recently been ravaged by Halifax manning personnel, and Murray warned that she ‘may be unfit for further duty at sea for some considerable period’ following the completion of her latest passage. Briggs was now the only qualified watch-keeper aboard Orillia, and the corvette had spent twenty-eight days at sea during the month of October.

“We are asking a lot,” Murray wrote. “of the morale of an inexperienced crew, to expect them to be happy, and remain in fighting trim and aggressive, in a ship in which they know their safety of marine accident, and not from any action of the enemy, depends upon the ability of their Captain to remain awake.”

Murray also noted that recent strong criticism of NEF by the RN was unwarranted but that this did not matter. By all standards Canada’s expansion fleet was dreadful, with few signs of rapid improvement. As one RN officer had informed a NEF counterpart. ‘Canadian corvettes are only useful for picking up survivors.’ Murray believed that it was possible to salvage the situation but that this required a radical alteration of the manning policy. All new commissions would have to work up from scratch, as the first corvettes had done. Permanence of crews and permanence of escort-group compositions were the touchstones of efficiency and should be adhered to as RCN policy. Murray offered to part with Prentice in order to upgrade the training establishment in Halifax. Unfortunately, his efforts came to naught. The RCN was quite prepared to accept a ‘temporary’ reduction in efficiency for the long-term benefits of producing a large cadre of experienced personnel. Murray and other senior operational commanders were informed of this policy in December. Bluntly put, the Naval Staff were not concerned with the operational efficiency of NEF or indeed of the corvette fleet in general. Heavy drafting from escorts committed to operations (with the exception of destroyers) continued, and no firm policy on the length of work-up periods for either new commissions or ships suffering from a high proportion of new drafts was laid down. All of this was left to the discretion of Captain (D), Halifax, by then Captain E.R. Mainguy.

(Numerous Allied warships in St John’s’ Harbour, circa 1942. Photo credit to The Rooms Provincial Photo Archive. Public Domain).

In light of events at sea, the navy’s adherence to such a manning policy and its failure to establish firm guidelines for proper work-up of escorts seems reckless. Not only did the manning policy contribute to the legacy of incompetence that plagued the expansion from this time forward, but it had more serious consequences. Unlike inefficiency in many other forms of military or naval endeavour, inefficiency in escort forces meant destruction for the men and ships that the escorts were trying to protect, not for the warships themselves. During the battle of the Atlantic, Allied merchant seaman paid for the RCN’s inefficiency. It was this that embittered Murray and the RCN’s vociferous post-war critic, Captain Donald Macintyre, RN. Elevating this deplorable condition to the status of policy was tragic. Moreover, it seems difficult to comprehend such a manning policy in light of the Naval Staff’s decision of the 11th of February 1941. At that time Staff agreed that it was an ‘unwise policy to relieve a large percentage of a ship’s company when that vessel was acting in a war zone.’ Ironically, the navy’s sound policy remained unaltered, but so did its definition of war zones. The war had indeed moved westwards, but this extension had drawn the U.S. into proclaiming a ‘security zone’ west of 26 degrees in March 1941, then into active naval operations in defence of trade in the same area by September. By fall of 1941 NEF was actually operating under the authority of a neutral power in a zone determined by the British and Americans to be inactive.

In these circumstances it was easy for NSHQ both to follow its manning policy with respect to the expansion fleet and to maintain the letter of the February statement. It would have been difficult, however, to convince anyone in NEF that its theatre was inactive in the fall of 1941.

Another reason for the Naval Staff’s reluctance to abandon its manning policy was pressure to increase the size of NEF as quickly as possible, hence the need to commission the entire first construction program promptly and get it to sea. Indeed, in mid-October Murray was informed that all available corvettes were to be sent to his command, not split among NEF, home waters, and overseas as originally planned. Thus, despite active American involvement in trade escort in the Western Atlantic, NEF’s responsibilities became the prime focus of RCN operations. By early December filly 78% of the RCN’s escort strength was assigned to St John’s. Newfoundland had become what the Admiralty had wanted it to be in June: the RCN’s number-one operational base. Yet facilities remained meagre, and the incidence of missed sailings owing to defects increased as winter took its toll.

(An unidentified RCN sailor on the docks of RCN facility in St John’s located on the south side of the harbour. Photo credit to The Rooms Photo Archives. Image exists in the Public Domain)

The dispatch of all available escorts and the arrival of NEF’s first training submarine did offer Murray some glimmer of hope. The idea of a training group was resurrected in early December, this time with a slight difference. With the large number of escorts now available Murray proposed to form one additional group in order to permit operational groups to slip out of their cycle on regular intervals to conduct training. Prentice and Chambly were to be detached to form the nucleus of the new training establishment. Anti-submarine exercises were planned for Conception Bay in conjunction with the training submarine L27, following which the group would sail for a twelve-day cruise, ‘in which all forms of attack, defence, and communications could be practised under ocean-going conditions.’ Here at last was a promising scheme to speed the advance of the expansion fleet towards full competence, or so it was thought. Murray’s letter to the naval secretary outlining the plan and requesting permission to implement it was dated December 7th, 1941.

(US Battleships aflame and settled on the bottom of Pearl Harbour, December 7th, 1941.)

By the time Murray’s letter reached the crowded desk of Captain J.M. Cossette, RCN, the naval secretary, the war was in a new phase. Not only were escorts badly needed off the American coast, but the Japanese advance in the Pacific had also brought crippling losses. The U.S. Pacific Fleet battle-line had been sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbour, followed shortly afterwards by Britain’s ‘Force Z,’ HMS Repulse and Prince of Wales, off the coast of Malaya. By the end of the year the American Asiatic Fleet, a small, weaker force based in the Philippines, was seriously exposed. Eventually it and the remnants of British and Dutch naval power in the South Pacific were lost in a vain attempt to defend Indonesia. The burden which the USN assumed in the North Atlantic with so much promise in the summer of 1941 therefore gradually fell back on the royals navies. Cossette politely advised Murray that new priorities precluded the establishment of a training group. The Naval Staff recommended that the whole idea be shelved until the spring or that training be conducted by senior officers during group layovers. the latter was a simply impossible plan, and its suggestion is evidence of the poor understanding the Staff had of conditions in NEF. Permanent groups and spare time had both fallen afoul of winter’s fury. Murray, now a rear-admiral with the title of flag officer, Newfoundland Force (FONF), scribbled a hurried ‘no action at present’ on Cosette’s letter, and the matter was temporarily laid to rest. For all intents and purposes NEF’s training group had been sunk by Japanese bombs.

(Joint RCN-RCAF Operations Room in St John’s, 1942)

Fortunately for the escorts and merchants ships plying the main trade routes, the last two months of 1941 brought a lull in German activity in their area. Despite Donitz’s protests, most U-boats were now sent to operate off Gibraltar and in the Mediterranean in response to British naval success against Axis supply lines to North Africa. During early 1942 emphasis switched to the U.S. east coast, and for more than half a year convoys were largely spared the nighttime pack attacks. For Allied sailors on the milk run, life on the North Atlantic, even without the Germans, was dangerous, demanding, and debilitating. In December 1941, Restigouche was crippled and nearly lost in a gale. Flooded fore and aft, foremast down across her deck and one funnel crumpled, she rode the storm eastwards to a safe harbour in Britain. On the same day the Japanese struck Pearl Harbour, the corvette Windflower was rammed by a merchant ship in heavy fog. The inrush of seawater detonated one of her boilers, and those nearby though she had been torpedoed. Sixty men were saved. She had sailed into the open sea eleven months before with a wooden gun barrel, and died without ever using her real one. The constant strain of operating a tiny escort in proximity to the often-invisible hulks of convoys was devastating. The Canadian navy had grown to 20,000 men by the end of 1941. Of these approximately 12,00 were at sea, many aboard the sixty-four corvettes Canada had by this point, many not long out of civilian clothes. Partly because of this, during the NEF’s first winter (1941-42) professionalism took second place to a rough pride in the ability to withstand constant suffering. Lieutenant Hal Lawrence, then serving on Moose Jaw, described it as a ‘macabre and desolate winter’ of ‘sleet, snow, rain, ice a foot thick on the forward superstructure: four hours on watch, two hours chipping ice, sleep and eat in between.’

“Aboard Moose Jaw,” he recalls “We were lucky. We had TWO prewar navy men on board: the captain and a leading seaman. Bread grows green mold. Dry clothes are forgotten. Exhausted men sleep where they can. But there is pride, even exhilaration, in a small ship beating a mighty adversary. The sea is neither cruel nor kind; it is indifferent.”

Alan Easton in 50 North: Canada’s Atlantic Battleground describes the exhaustion of convoy work present even with minimal enemy activity:

"… After my first voyage I became convinced it was the merchant seamen who suffered most. They could not really fight back, or even maneuver enough to avoid attack. They presented the best targets and never knew when they would be singled out for extinction. The suspense must have been awful. These men tramped from Cape Town to Rio alone and unprotected, some few had old naval guns. Crossing an ocean where the U-boats prowled and the fear of the mighty German surface raiders hung over their heads. Up the Brazilian coast and through the Indies, still alone, to North America, their lives in constant jeopardy. Off the UK, finally across, they had to contend with new enemies, the speedy E-boats, mines, and the Luftwaffe. Few knew the colossal tasks these unsung heroes achieved. They were overshadowed often by the epics of fighting men who had done no more and sometimes less. If they came home, which thousands never did, they soon had to go out again and repeat it all over again.

We navy men, for all our suffering, did not go through near as many torments as they did, nor did any other fighting service. A merchant seamen could fortify himself with nothing but hope and courage. Most of them must have been very afraid, not for days and nights but for months and years. Who is the greater hero, the man who performs great deeds by swift action against odds he hardly has time to recognize, or the man who lives for long periods in constant, nagging fear of death, yet carries on?

This war the merchant seaman fought, this war we fought beside them, could be terribly tiring. Once, in the 56 hours after a first ship had been torpedoed in one convoy, my snatches of sleep totaled about 3 and a half hours. Perhaps it was not surprising then, as we straightened away with the job over, that I could speak, coherently, only about half a sentence as I tried to give my navigator my final instructions. My words would dwindle into nonsense. I struggled against this and by standing erect and moving about a little on the bridge I thought I eventually conveyed my wishes to him. Then I went below and collapsed into my bunk.

Two years later I met the navigator and asked:

“Do you remember when we turned north for Reykjavik after that action? It was a bit after lunch and I was going down to turn in.”

“Yes,” he answered. “I remember turning north and taking over.”

“Do you know,” I said, “I was so tired that I was falling asleep as I was speaking to you. I felt embarrassed in case you noticed it. Did you?”

“Did I?” A broad grin. “No, sir. I was too sleepy to know what the hell you were talking about.”

Our enemies were fatigue, U-boats, and the weather. The latter doubly so in winter. One dark night, making for port after leaving the convoy and running before a high quarterly sea, the ship was pitching and rolling deeply, slowly; too slowly, the waves almost synchronized with her speed. At time she rode like a surfboat before the rollers with her nose pointing down. At 20:45 the stern rose high and the ship rolled 50 degrees to port and hung for an interminable time until the great sea relented and plowed forward along the keel. When the leading seaman of the watch was able to check several minutes later, the after-lookout man was not on the high-gun platform. The bulwarks on the starboard quarter were bent inboard, the protective plating on the gun platform almost flattened and the large raft on the port side was gone. Damage that told that the lookout had been swept overboard. The great sea must have buried the whole after end of the ship.

We turned to search but as we rose and dived into the steep seas we knew we could never find him. His close friend and shipmate cried for days and nights…

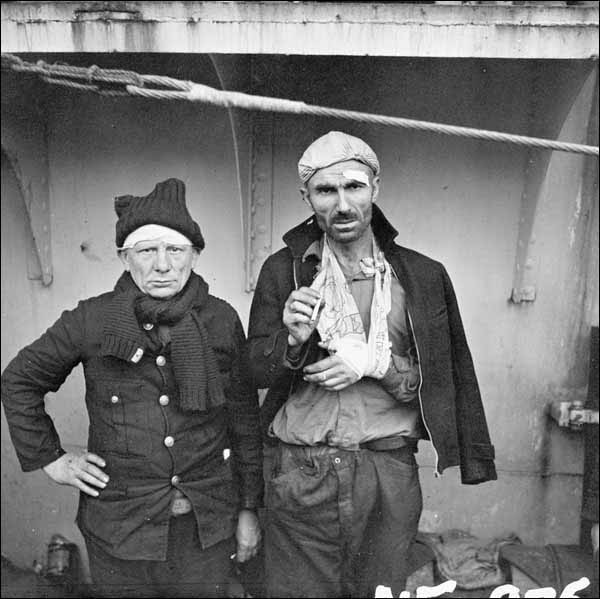

(Two unidentified merchant mariners who survived the sinking of their ship. Picture taken in St Johns in 1942.)

All corvette sailors remember their ships as a source of numbing fatigue and indescribable discomfort. Conditions were aggravated by overcrowding since by 1941 corvettes already carried twice the crewmen allowed for in the original plans. Men slept where they could: on lockers, table-tops, or in some dark, special place that offered a little warmth. Even in moderate seas the ships pitched and rolled violently, and most men spent their first weeks desperately ill. Water dominated a corvette sailor’s existence. It permeated the entire ship, soaking the men and their food. ‘An almost constant cataract of water poured across the focsle and down into the well deck amidships.’ Williams Pugsley wrote after the war. It was simply impossible to bring good from the galley (aft of the wheel-house) through this torrent to the mess-decks forward. The men of the escorts survived on a diet of hard tack, pickled beef, and lime juice- Nelson’s fare, but the only diet that would endure the hardships of corvette life. At action stations men were continuously drenched in spray, while water cascaded down into living spaces through hatches left open to permit access to magazines. Water covered the decks inside and out and dripped incessantly from condensation on the deckhead. Once a sailor was wet, it was impossible to get dry again. Men ‘just wore their wet clothes wet till they dried in the wind.’ perhaps the final indignity was the straight pipe which ran from the toilets to the open sea. Harry Shorten, a telegraphist aboard Dundas in 1942, recalls that if you happened to be sitting on the seat ‘and she rolled, you got a four-inch jet of icy Atlantic up your behind.’

The suffering of men was perhaps greatest during the first winter of 40-41, when few were inured to the sea and the corvettes had not yet received the most rudimentary improvements. A year later the ships were much the same but the weather was worse and the mess-decks even more crowded. If the Americans found the North Atlantic in winter a difficult place to maintain a professional service it was unlikely that the RCN would have much luck building one there.

Donitz hoped the U-boat war would spread quickly following the American declaration of war, but it was not to be. His initial hopes for a rapid descent into US coastal waters were forestalled by the German naval high command, which wanted pressure in the Mediterranean maintained. It was not until early January 1942 that the first five U-boats were freed up for action in the Western Hemisphere. They made a purposely quiet passage, hoping to take the Allies by surprise, but their movements were watched closely by Allied intelligence, Despite this foreknowledge, American preparations to meet the threat were grossly inadequate, and the first German campaign in the Western Atlantic was to be highly successful. From the 12th of January to the end of the month, forty ships, all sailing independently, were sunk by U-boats west of 40 degrees. This figure continued to rise in February and March, until in excess of 90% of all shipping lost in the Atlantic fell of the American coast. The Germans sailors would name this “the second happy time” or “the golden time”. Officially it involved several German naval operations including Operation Drumbeat and Operation Neuland. German submarine commanders would come to call it the “American Shooting Season”.

To the British and Canadians, American failure to introduce convoy seemed inexplicable, particularly in light of the free access to Commonwealth experience extended to the USN for years previously.

(Merchant Vessel Dixie Arrow, torpedoed off Cape Hatteras in March 1942.)