DISCLAIMER: The vast majority of this information is either directly quoted from the sources below or only slightly changed. Very little of it is my original thoughts, save a paragraph here or there. I attribute the following completely to my sources and make no claims otherwise. If so desired I will remove this content from the website without hesitation if asked to do so by TIMEGHOST or by any of the original copyright holders. My intent is purely the sharing of historical knowledge regarding Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic.

Sources:

“The Far Distant Ships” by Joseph Schull, ISBN-10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

“North Atlantic Run” by Marc Milner, ISBN-10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Joseph Schull’s work, published 1985)

“Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War: Volumes 1 & 2” ISBN-10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

Aftermath of SC-42, Radio Detection and Ranging, Two Navies,

Given that operations in the Western Atlantic were (For the time being) an American responsibility, the RCN approached the USN for help with SC convoys. Commander F. Houghton, the director of Plans and Signals, who was in the US Atlantic Fleet, broached the issue with Admiral E.J. King, then commander of the US Atlantic Fleet, and sent Admiral King’s reply to Ottawa on the 23 of September. It was a flat no. ‘I gathered that one of his difficulties,’ Houghton wrote to Nelles, ‘was the length of time his ships were not running due to refits and time in dockyard hands for fitting of new material.’ Houghton’s mission had little chance for success in any event. King was a notoriously obstinate and prickly character and a great burden on his peers. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, later the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, confided to his diary that the whole war effort would have gone more smoothly had someone shot Ernie King. Eisenhower’s Commonwealth colleagues would have agreed, and King’s tendency to dismiss Anglo-Canadian ideas proved a serious impediment to the Allied campaign in the Atlantic. King impressed on Houghton his belief that SC convoys were a joint RN-RCN responsibility, which was hardly the agreement reached at the Argentia meeting. It was, however, indicative of the American tendency to view the two commonwealth navies as some form of joint entity (which, in fairness, they mostly were). But King was also known to dislike the idea of escort groups of mixed nationality, a sentiment which, at least in so far as the USN was concerned, Canadian authorities shared. Faced with this obstacle, the Admiralty agreed to leave some of their destroyers in NEF, although this component of the force’s strength fell from nine in September to five by October, where it stayed for the balance of the winter. The Americans later agreed to help the RCN ‘if the situation became more critical.’

The ineffectiveness of SC-42’s screen was also a function of the action of the escorts themselves. Orillia’s detachment to salvage Tahchee and the tendency for inexperienced corvette commanders to busy themselves with rescue work contributed to further losses. While this was bad enough, the corvettes failure to maintain proper communications with their SOE was even more unfortunate. Hibbard commented in his report that his use of radio had, by 1941 standards, been excessive. But in a tactical situation, when the whereabouts of the convoy was already obvious to the enemy and particularly with a new group, no amount of effective and efficient use of radio could be excessive. In fairness to Hibbard and the escorts of the Twenty-Fourth Group, their task was a daunting one: to defend sixty-five ships in twelve columns spread out over thirty square miles in the face of at least fourteen U-boats. Further, it was hard enough to detect a U-boat travelling hull-down in the inky blackness of high latitudes, but the moderate to heavy swell and the slight spray from the wind on the wave-tops made the task well-nigh impossible. The prevalent surface conditions coupled with a near-full moon and otherwise good visibility (three to five miles) made ideal conditions for U-boat operations. At night they could easily see without being seen. On top of this, the escort was frequently called upon to make asdic searches for contacts reported inside the convoy. The turbulent waters in the convoy’s wake made this task pointless, while the constant emergency turns rendered relative positions of sightings useless as the basis for starting searches. Unable either to prevent attacks or to deal effectively with intruders once sighted, the escorts turned to rescue work. Had they remained at their posts their deterrent effect might have saved some ships. It is plain, however, that the tactical necessity of maintaining the deterrence was poorly understood by the escorts, while their natural desire to help those in distress proved too strong. All of this points to poor training and a failure both to comprehend and to follow the WACIS sections on the conduct of escort.

(Mate A.F. Pickard and Chief Engine Room Artificer W. Spence, St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1942. Both men played key roles in Chamblys sinking of the German submarine U-501 on 10 September 1941, the Royal Canadian Navy’s first confirmed submarine sinking of the Second World War. Pickard received a Mention in Despatches and Spence received a Distinguished Service Medal for their actions.)

The successful destruction of U-501 in the shortest possible action was an equal combination of skill, good luck, and inexperience on the part of the enemy (U-501 had only commissioned four months earlier). For the latter reason it was, perhaps, a fair contest for the RCN, but the action illustrated the accuracy which a good asdic team could bring to an attack. It also illustrated Prentice’s preferred method of depth-charge attack by corvettes, one which he encouraged. The order to reduce speed upon attacking was in direct contradiction to the accepted British practice. The RN was trained to stalk a U-boat from an initial range of twelve hundred yards, tracking the U-boat at the ship’s best asdic speed (which was usually about twelve knots) to the throw-off point. At the latter point, still eight hundred yards distant from the submarine, speed was to be increased and the course altered to lay the depth-charge pattern ahead of the target. Increased speed allowed the corvette to close the distance to the target quickly, thus reducing the U-boats time for evasive action. It also carried the attacking ship well clear of its own explosives. Prentice believed that the corvette’s short turning radius (four hundred yards) coupled with the known limitations of type 123 asdic demanded more resolute action.

He advocated a much shorter initial range, a steady speed for attacks (roughly equivalent to best asdic speed), and a much closer throw-off point - half the distance recommended by the RN. This allowed the target to be held by the asdic operator until the last possible moment, while the steady speed gave no warning to the U-boat of impending attack, thus reducing the likelihood of successful evasive action. Employing Prentice’s method it was theoretically possible to launch a rapid series of accurate attacks. Prentice even went so far as to have a transparent ‘rate recorder’ (indicating the change of target distance) prepared and fitted to Chambly’s asdic to facilitate these short, quick, depth-charge actions (such a rate recorder was later adopted by the RN as standard equipment although there is no evidence to support that the idea was solely that of Prentice). Although the quick attack paid off handsomely against U-501, it had a serious drawback. If the charges were set shallow or the escort lost too much momentum from the application of her helm at the throw-off point, there was a danger of damage from her own explosives. In one of the last depth-charge attacks undertaken by Chambly around SC-42, electrical fittings in the after portion of the ship were blown, and the engine and boiler-room personnel reported being lifted six inches off the deck by the force of the exploding charges.

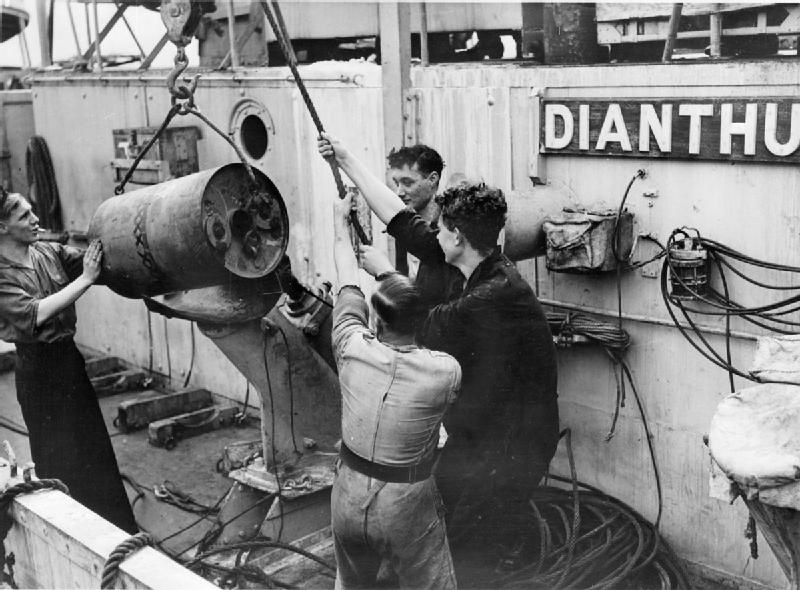

(Crew members loading a depth charge into the midship charge thrower, HMS Dianthus, October 1942)

The lessons of SC-42 were fairly obvious, and they suggested nothing of which the RCN was not already aware. Newfoundland Escort Force was organized into proper escort groups and had been since May. Teamwork would come with time and effort. Radios were either already fitted or on their way. Aside from a shortage of starshell, flashless powder, and searchlights (Kenogami was criticised for not illuminating her U-boat with a searchlight), the real equipment shortfall during SC-42 was the lack of effective radar. The RCN was slow to appreciate the potential of radar for small ships. Its uses in naval gunnery were understood, but none of the Canadian fleet warranted fitting such equipment in 1939-40. While future needs might require expertise in the field, sufficient instruction was available through the RN, where Canadians were exposed to larger ships and gunnery radar. Moreover, there was a great need for radar officers and technicians in Britain early in the war, and by 1941 Canada had been picked clean of her available expertise. The first training course for naval radar officers in Canada was actually inaugurated to meet the growing need overseas. The RCN had precious little to do with this first class, and when approached to provide $2500 to finance instruction of the eleven candidates, declined to do so. It is statement enough of the navy’s lack of interest in radar that the first class, given by the University of Toronto, was sponsored by the local Kiwanis Club. All the candidates were successful, and the RCN belatedly granted them commissions in the RCNVR before sending them overseas to serve, on loan, with the RN.

Towards the end of 1940 the RCN finally began to appreciate the need for radar personnel of its own, but by then the readily available manpower had been gobbled up by the army, the air force, and the RDF (Radio Direction Finding) Imperial Forces Recruiting and Training scheme. It was now necessary to train men from scratch, and the RCN lacked both instructors and facilities. A few positions were available at the army’s radar school in Halifax, but, as the Naval Staff, noted rather quixotically, this was largely and army and air-force program. In any event, radar policy remained undefined in early 1941, and until that of the Admiralty respecting escort vessels was ascertained, the Naval Staff took no action. News of British practice and policy reached Ottawa in February 1941, at which time authorities in Ottawa took immediate steps to acquire radar for the fleet. They approached the National Research Council, also the navy’s research and development establishment, to ask if the NRC could develop a radar for the detection of submarines on the surface at night. The navy requested specifically that the set be compatible with comparable British equipment. The NRC was already involved in radar and was working on a variation of the British ASV or 1.5 metre set, an airborne version of the RN’s Type 286 radar, the type then fitted in escort destroyers.

On 19 March 1941 a special meeting of the Naval Staff and NRC officials was held, during which the issue of radar was thrashed out. Dr C.J. Mackenzie, head of the NRC, explained that they were working on ASV and that this set was now being fitted to escorts of the RN. ‘As the immediate requirement is locating submarines at night etc.,’ Dr Mackenzie stated, ‘this simpler set will be sufficient for our needs particularly as these can be produced at short notice in Canada.’ The decision whether or not to build a new 1.5 metre set or simply to produce a Canadian version of the 286 was to be made following trials in April.

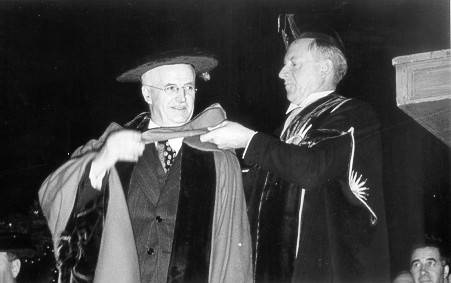

(Chalmers Jack Mackenzie (left), receiving an honorary degree from the University of British Columbia, October 1947. Photograph credit to the University of British Columbia)

The NRC constructed the first Canadian submarine-control (CSC) radar with dispatch. It was ready for sea trials on the 12th of May, 1941, only fifty-four days after the RCN had made its initial inquiries. Interestingly enough, the first trial set went to sea in Chambly. There, under the careful, practised hands of NRC boffins, project engineer H. Ross Smith, and the watchful gaze of Prentice, the new radar performed admirably. The second day of trials, conducted in company with another corvette and the Dutch Submarine O-15, revealed that the set worked very well indeed. The sub was tracked at ranges between 2.7 and one-tenth miles (there is no indication that O-15 proceeded with her deck casing awash in the manner of an attacking U-boat, and it is likely she was fully surfaced), and bearings were regarded as unerringly accurate. On May 16th further trials were undertaken, this time simulating an attack on a convoy. According to NRC personnel, naval authorities were completely convinced of the value of the set. On the 20th the Naval Staff instructed that all escorts should be fitted, and the NRC agreed to provide the first fifty sets from their own laboratories. Further orders were placed with Research Enterprises Limited of Toronto.

(The now infamous SW1C radar system. Pictured here is the ‘Yagi’ antenna atop a Bangor minesweeper.)

Once alerted to the need, the Naval Staff and Canadian scientists had moved with commendable speed. However, it is noteworthy that at the same time that Chambly was testing a new Canadian 1.5 metre set, HMS Orchis, also a corvette, was conducting trials in UK waters with a 10-centimetre set, the Type 271- the radar which was to contribute so greatly to successful escort operations in 1942.

The production model of the Surface Warning, First Canadian (SW1C), as the CSC came to be known, differed little from the set tested in Chambly (which was removed following the trials, Prentice had to wait until 1942 to get one of his own). It consisted of a masthead ‘Yagi’ antenna, comparable to the roof-top television antennas so common after the war, made of copper, from which signals were both emitted and received. The antenna was mounted on a steel shaft which, held in place by a series of bearing-lined brackets, ran down the mast into a gearbox fitted at the bottom, level with the forecastle deck. From this main weight bearing assembly the transmitter-receiver cable and manually operated driveshaft ran to the forward port side of the deckhouse. In what had been the officers’ water closet a radar room was constructed, housing the set and large handwheel and bearing indicator used to direct the antenna. A cathode-ray-tube indicator gave the operator the necessary information on strength and character of echoes.

Like all early radars, the SW1C was a fickle instrument. It had to be rested periodically and had to be started and shut down in a proper sequence to avoid damaging the electrical components. Aside from requiring that such precautions be taken against overheating and improper procedures, the vacuum-tube technology of early radar, particularly Canadian-built sets, took constant maintenance and suffered greatly from the shock of depth charges, firing of the 4-inch gun, and the general pounding of the ship at sea. The SW1C had other limitations. Its search area was limited to a narrow cone ahead and a very small ‘back echo’ astern of the antenna. The SW1C could ‘sweep,’ unlike the fixed British 286 set from which it was developed, but the rotation of the antenna was manual (by hand crank, sometimes by automobile steering wheel). If the set was not directed at a suspect target, the latter went unseen. The significant advantage of the 271 set just entering British service was that it did sweep to a full 360 degrees automatically, although it took what now seems a rather ridiculous amount of time to do so (two minutes). Further, the first Canadian set, like its early RN counterpart, had a very long wavelength of 1.5 metres. Much too long, in fact, to give a sharp definition to small targets among the clutter thrown up at sea level. The 271 set overcame this problem by using an extremely short wavelength of 10 centimetres, which returned a sharp echo.

Initial supplies of SW1C were disappointingly slow, and by the end of 1941 only fifteen RCN corvettes were fitted. In contrast, all the destroyers carried the British 286, and at least one of the ten ‘British’ corvettes was already equipped with the new type 271. By the end of the winter of 1941-42 all RCN corvettes did have some form of radar, yet for all practical purposes the early radar sets made no appreciable contribution to escort operations, except perhaps to provide crews experience in caring for the new technology under trying conditions. From August 1940 to February 1942 only four U-boats are known to have been detected on the surface with the aid of radar, and of this number only one was attacked. Even if this figure, which is based on admittedly incomplete data, is grossly inaccurate, doubling, tripling, or quadrupling it still produces an incredibly low number of contacts. It may well be, as the commanding officer of Orchis reported after several months at sea with his new 10-centimetre set, that it took considerable time for both operators and bridge personnel to become adjusted to a radically new innovation. It is also true that both the 286 and the SW1C were failures as surface-warning sets, particularly against hull-down U-boats. Still, that the SW1C and its successor the SW2C proved to be unsuccessful under operational conditions tends to overshadow the remarkable achievement of the navy, industry, and science in fitting out the fleet with radar in much less that a year. Unfortunately, development and supply of a Canadian built 10-centimetre radar did not go as smoothly, and this was to have important consequences at sea.

(The SW1C radar station aboard HMCS Montreal, taken 7th October 1944. Public Archives Canada Photo)

As the summer of 1941 gave way to autumn, any spare time previously enjoyed by NEF quickly evaporated. In part this stemmed from the simple increase in the basic size of escort groups. But it was also the result of factors well beyond the immediate control of RCN authorities. In mid-September the Mid-Ocean Meeting Point was moved eastward from 26-30 degrees West to 22-26 degrees West, following an agreement by RN and USN staffs, in order to free three RN escort groups for duty in the South Atlantic. The extended length of passage for NEF and lack of any corresponding reduction in the convoy cycle eroded the escorts’ harbour time. In addition, evasive routing drove convoys farther and farther north through later 1941, lengthening mileage logged and forcing escorts and merchantmen alike to endure the foulest weather the North Atlantic had to offer. NEF escorts were supposed to have twelve days of every convoy cycle free, but in practice spare time never approached this figure. Chambly, for example, averaged twenty-six of every thirty days at sea during the last three months of 1941, barely enough time left over for boiler cleaning.

By mid-October the increased amount of sea time logged by the NEF led Captain (D) Newfoundland, Captain E.B.K. Stevens, RN, to send a strongly worded memo to Murray. In no uncertain terms Stevens chastised Murray for measuring an escort’s endurance solely on its fuel capacity. He warned that unless immediate steps were taken to reduce the amount of sea time, ‘a grave danger exists of breakdowns in health, morale, and discipline.’ Murray was sympathetic and could see first hand the effect that strenuous operations were having on his command. Many of the escorts were still undermanned, and the general shortage of personnel kept him from forming a manning pool ashore to provide reliefs. The situation was so tight, Murray confessed, that he was forced to send defaulters back to sea, a sentence few can have though lenient. In any event, so long as schedules were left unchanged and escort groups were to sail at maximum strength, there was little Murray could do. Even the Americans were worried by mid-October. Captain M.L. Deyo, USN, destroyer squadron commander at Iceland, advised Admiral Bristol that the RCN was already near a breaking point:

“As I understand it, they want to make quick turn around at this end in order to get more time in home ports. Having only six units, their cycle is 36 days with convoy intervals of 16 days. This gives them 10-14 days at home. The pinch comes when they have a maximum of 2 days which is often reduced to 36 hours or less and they are feeling the strain. The voyage out takes them 11 days. They arrive here tired out and the DDs barely just make it… With winter coming on their problems will be more difficult. They are going to have breakdowns and ships running out of fuel at sea.”

In large part the problem of too-extensive layovers in Iceland, towards which Captan Deyo’s remarks were largely directed, arose from the slightly unsynchronized convoy cycle. NEF escort groups were having to lie In Hvalfjordhur awaiting the next slow westbound convoy as it fought its way through prevailing winds and weather. The Americans were sympathetic to the Canadian plight, and on October 9th Admiral King, authorized the assignment of westbound convoys to NEF on a priority basis. But with the onset of winter weather in the late fall, the pressure on NEF increased. Even the British admitted in late November that the Canadians were working twice as hard as Western Approaches escorts and suffered the added burden of almost totally inexperienced crews. Finally realizing just what a strain NEF was under, the Admiralty’s director of Anti-Submarine Warfare apologized to Murray in December for being ‘far too critical’ in his assessments of recent Canadian actions.

The harsh climate of the North Atlantic, coupled with the demanding task of escort operations in small ships, made proper rest for the crews an important element of operational efficiency. This was particularly the case when the gales of November set in. But even in the summer of 1941, USN officers were shocked by the ill-kept appearance of British escorts they encountered off Newfoundland. Initially Americans could not understand why the ships’ crews were not turned to with ardour to chip and paint ship during layovers. Once they were committed to operations in the North Atlantic, this wonderment ceased, and the USN, which hat not yet undergone rapid wartime expansion, found the Newfoundland-to-Iceland run a serious impediment to operational efficiency. One American later wrote of the USN’s impressions.

“Escort operations in the North Atlantic were physically demanding because of the stormy weather, and emotionally enervating because of the need for constant vigilance in a tedious enterprise and strain of making rapid decisions involving the fates of men and ships on the basis of incomplete information. The stress sometimes induced fatigue and irritability which had to be treated byrest, lest it lead to a nervous breakdown.”

The impact of these conditions on the smaller ships of NEF can be imagined. Small wonder that Canada’s first corvette captains, more often than not the only qualified watch-keepers on their ships, were preoccupied with things other than maintenance and training during their brief layovers.

Even before NEF was beaten into submission by the North Atlantic, the slow march to efficiency animated both RN and RCN officers. In mid-September SC-44 lost four ships and the corvette Levis in one night’s furious action.

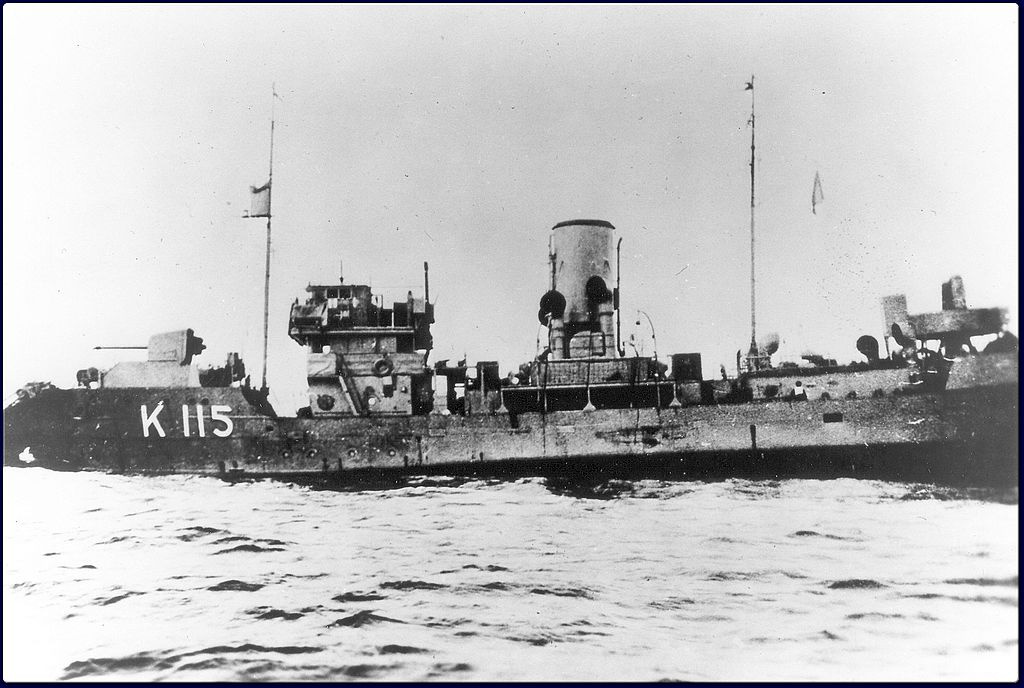

(HMCS Levis, lost on the 19th of September, 1941. Torpedoed whilst escorting convoy SC-44 by U-74. This photo taken on that day. Her destroyed bow can be seen, as can listing due to the flooding.)

At 6:03 AM on the morning of the 19th, U-74 fired a spread of four torpedoes at convoy SC-44 and observed four hits, two different ships and two per ship, a merchant vessel and a RCN warship, both reportedly sank within short order. The Allied report is quite different, stating that HMCS Levis and Levis alone suffered only one hit. Myself considering the Allied report to be more accurate, HMCS Levis was struck near the bow, and in fact most of it was seperated by the blast. The crew abandoned ship, but two hours later the Levis was still afloat. HMCS Mayflower moved in and secured a tow line, which snapped not long after, and had to be re-attached (which took some 90 minutes, time spent away from the convoy). The tow was uneventful after that until at 19:10, the damage to Levis finally proved too much and the ship capsized and sank. 18 ratings were lost (some in the initial explosion), and the survivors were picked up by Mayflower and Agassiz. Lieutenant-Commander C.W. Gilding was heavily criticised for ordering abandon ship without assessing the damage first. It was another example of the general inexperience of many RCN Reserve officers. Levis was the first of the Canadian corvettes to be sunk by enemy action. SC-44 would go on to lose four more merchant vessels.

Here I would take a moment to discuss a post-war interpretation of the RCN made by corvette officer by the name of James B. Lamb. A native of Toronto, James Lamb joined the RCN in 1939 and spent the Second World War on several corvettes. He commanded HMCS Minas and later HMCS Camrose, in which he served from December 1944 until the end of the war.

In his book, The Corvette Navy, he describes “The Two Navies”. His interpretation of the differences between regular RCN officers and ratings, and the reservists who manned the corvettes.

"Canada had two navies in the Second World War. First, of course, was the Royal Canadian navy, the big navy, the “real” navy, the “pusser” navy. It was, as its corps of public relations officers endlessly reiterated, a very big deal indeed. Thousands upon thousands of men and women would fill teeming offices and training establishments, vast and ever-growing complexes of brick and concrete, representing the investment of hundreds of millions of dollars. It’s organization, in the end embracing dozens of commands, hundreds of departments, and thousands of experts and specialists, ranging from physicists to dietitians, from jurists to journalists, was a triumph of administrative genius that would ultimately represent one of the nation’s major wartime accomplishments.

It is fashionable in peacetime to deride the capacity of service bureaucrats, but not even General Motors or any other of the civilian corporate giants has ever managed, in time of peace, anything to compare with the administrative miracle of the wartime RCN, which grew from eighteen hundred officers and men into a vast and complex machine of almost a hundred thousand men and women. Here was the repository of naval tradition, the showcase of talent and ability, the dynamic centre of thrust and growth and expansion. Vast though it was by mid-war, it yet thrived and gew in every direction as busy men were driven to seek more assistants, more space in which to operate. Here was pay and pace and promotion, here was where it was all at.

A vast fleet of vessels of every sort was attached to this great navy; literally hundreds of coastal motor launches, harbour craft. and training vessels, armed yachts and gate ships, harbour minesweepers and picket boats; all the endless numbers and variety of ‘9 to 5’ fleet. But the real strength of the Big Navy lay ashore. its admirals flew their flags from office buildings, and its officers and men, ratings and Wrens, had their wardrooms and messdecks in shore establishments, land-bound warships these, bearing old and famous naval names.

It was a tremendous force, embodying some of the best brains in the country and involving a significant proportion of the nation’s wealth and manpower. Although manned by reservists in their thousands, it was directed by professional naval officers, and its operations were oriented to a hierarchy that included every senior officer the country possessed, or could borrow from abroad. What it all accomplished would be difficult to define, but of necessity it was preoccupied with recruiting, training, housing, feeding, administering, and caring for itself, a great and endless task.

Canada’s second navy was a much different force: a bunch of amateur sailors, recruited from every walk of civilian life, manning ships once deemed too small for command by professional naval officers. The ships- Algerins, corvetets, frigates, Bangors- were as cheap as they could be built, and their officers and men were involved, not with Admirals and Captains, but with characters like Two-Gun Ryan, Harry the Horse, Death Ray, Foghorn Davis, The Mad Spaniard, and Monocle Prentice. It was amateur, improvised, cut-rate navy, but its purpose and accomplishment were clear: it fought, and won, the Battle of the Atlantic. This was the corvette navy, the little navy, Canada’s other navy, manned by amateurs like me.

The division between the two navies was surprisingly complete and clear-cut; few regular career canadian naval officers ever kept watch aboard a corvette, and only a handful of corette crewmen were RCN ratings. For shortly after the outbreak of war, a strange process began. The little handful of professional naval officers, all that the country possessed and the only Canadians trained over long peacetime years to fight a war at sea, were bustled ashore into offices. There they presided over clerks and typists in a series of administrative posts for which they had received no training at all. Most of them never went to sea again.

Their places afloat were taken by a handful of former merchant seaman, now officers of the Royal Canadian Reserve, and by young men in the Royal Canadian Volunteer Reserve, many of whom were culled from offices ashore, and most of whom who had never been to sea before. It was a situation worthy of a comedy routine: trained seamen were put in offices ashore and trained office managers were sent to sea. As a result, Canada’s professional naval officers were to play an ever-diminishing role in the Battle of the Atlantic. A miscalculation brought about by the assumed role of the corvettes and the assumed ability to acquire destroyers. The few sent to sea were allocated straight to the navy’s River-class destroyers, what was felt to be an ‘appropriate’ command."

If this excerpt seems out of place, I apologize for the scatterbrained nature of my retelling of Canada’s Battle of the Atlantic. I only wished to highlight the irony present in the situation, and to show that even by the end of 1941 and beyond, Canadian naval officers with experience and training were still being held ashore for when the real “expansion ships” (The Tribals) arrived to fight the “real battle”.

(An Allied convoy heads eastwards, bound for Casablanca, sometime in 1942)