DISCLAIMER: The vast majority of this information is either directly quoted from the sources below or only slightly changed. Very little of it is my original thoughts, save a paragraph here or there. I attribute the following completely to my sources and make no claims otherwise. If so desired I will remove this content from the website without hesitation if asked to do so by TIMEGHOST or by any of the original copyright holders. My intent is purely the sharing of historical knowledge regarding Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic.

Sources:

“The Far Distant Ships” by Joseph Schull, ISBN-10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

“North Atlantic Run” by Marc Milner, ISBN-10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Joseph Schull’s work, published 1985)

“Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War: Volumes 1 & 2” ISBN-10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

**The Americans, Doctrine Woes, The Pack Explained, **

According to operational plans already worked out under the terms of ABC 1, the US commitment to Support Force was large, included within were battleships, a large force of escort destroyers (48), and, in the event of war with Germany, fleet-class aircraft carriers. The intention of the Argentia agreements was to relieve the RN of the burden of the Western Atlantic, including defence of trade. As far as the escort of convoys was concerned, Support Force was initially responsible for protection of fast convoys only between WESTOMP (the limit of local RCN escorts) and MOMP. The RCN commitment to the Western Atlantic, outside of local duties, under the terms of ABC 22 and the operational orders prepared by the USN was five destroyers and fifteen corvettes. With these forces the RCN was to assume sole responsibility for slow convoys between WESTOMP and MOMP. All British escorts operating west of MOMP were to be withdrawn, and it was expected that when the USN had gained sufficient experience in the conduct of convoys, it would take over NEF’s duties as well. In the interim, NEF passed from the operational control of C-and-C, WA, to that of Rear-Admiral A.L. Bristol, USN, Commander, Support Force, an officer whose nation was still neutral.

(HMS Prince of Wales, Placentia Bay, August 1941. She carried Winston Churchill to his first face-to-face meeting with Roosevelt here).

The agreements reached in Placentia Bay illustrate the Anglo-American tendency to take decisions affecting the operational deployment of the RCN without direct consultation with Canadians at any level. Canadians were not so petty as to resent active American involvement in the war in aid of the Commonwealth, nor did they underestimate the importance of firm direction of the war effort. But the imposition of an American admiral on to the fabric of an emergent Canadian naval commitment, and in the midst of an enormous expansion, had serious lasting consequences.

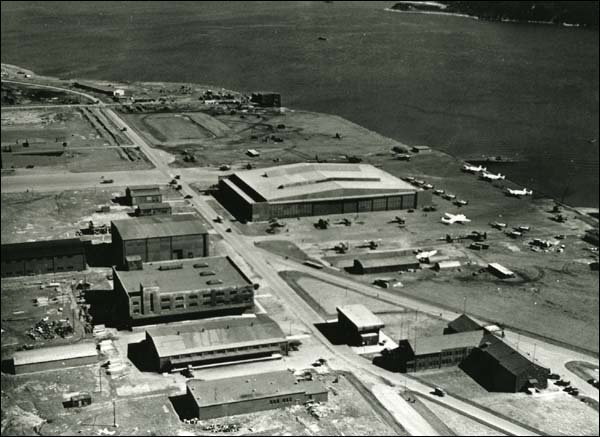

(US Naval and Seaplane Base at Argentia Nfld. 1943. The US Army would also establish Fort McAndrew nearby, for the sole purpose of protecting the Naval and Air Force facilities.)

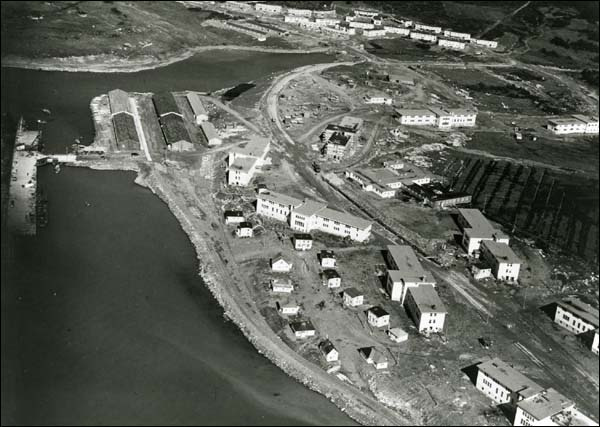

(Fort McAndrew, Argentia, Newfoundland, circa 1942)

Admittedly, Canada’s naval effort was just that, emergent, but the ill will generated by the failure to include Canada in decisions directly affecting her war effort could easily have been avoided. Murray was known to be particularly annoyed at this shoddy treatment, although his relations with Admiral Bristol were always cordial and efficient. Perhaps the most important long-term effect of American involvement in the Northwestern Atlantic in 1941 was the confusion it introduced into the RCN’s plans and development. While much of this is difficult to document, it is clear that uncertainty over the future of the base at St John’s delayed work on that base. In many respects the delay was more than compensated for by RCN access to the American naval-operations base at Londonderry in early 1942. More problematical was the effect of operations alongside the USN on developing RCN tactical doctrine.

While professional naval officers never lost their close ties with the RN, the more proletarian wartime navy felt greater affinity with its North American counterpart. Left to deal with only one authority it is likely that the RCN would have made quicker and surer advances towards the type of operational efficiency expected of them by the RN during 1942 (after the USN had largely withdrawn). But the infusion of the inexperienced USN into NEF’s theatre brought a concept of ASW very different from that which developed in the RN, and this despite the interchange of such information.

By the spring of 1941 the RN had finally resolved its internal squabbling over the purpose of escorts in favour of defence. In April Western Approaches issued its famous ‘Convoy Instructions’ (WACIS), which set the doctrine for convoy escort down on paper. The first and primary task of the escort was to be the ‘safe and timely arrival of the convoy.’ All else, including pursuit of the enemy, was secondary to this aim. In practice WA Staff officers preferred to see safe and timely arrival tempered with aggressive pursuit of the enemy if time and circumstances permitted. But unless the escort could balance losses from its convoy with destruction of the enemy, it was best to push U-boats off and return to station in the escort screen. In contrast, the American concept of convoy escort had not progressed beyond the pre-war British belief in offensive escorting. United States Navy ‘Escort-of-Convoy Instructions,’ in use in the fall of 1941, placed ‘conduct of the convoy clear of the enemy’ last on its list of priorities, exactly opposite to what RN preference had become.

In retrospect, the passing of NEF from RN to USN command could not have come at a worse time. The expansion fleet needed the guiding hand of a consistent and well-defined doctrine. The RCN did adopt WACIS as the basis of escort operation, but the British would argue (and have argued since the war ended) that the spirit of its escort sections (the primacy of safe and timely arrival of the convoy) was absent from Canadian operations. In this the RCN was at least consistent with its earlier aim to conduct ‘offensive’ ASW, through the provision of corvette ‘strike forces’ for example. It was natural, therefore, for the Canadian navy to exhibit such tendencies in its escort operations. Moreover, whereas Western Approaches Command was a specialized force tasked exclusively with trade protection, Canadian escort forces remained part of the mainstream of the RCN. The sharp distinction, as it made in the much larger RN, between what the main fleet was to do and what was expected of trade escorts was never clearly delineated in the early days of RCN expansion. Escort of trade convoys was what the whole navy did. And yet, within that fleet there beat the heart of a more traditional service, one which aspired to cruisers and destroyer flotillas. Operations under the USN, reinforced the RCN’s natural tendencies, to the detriment of the navy in British eyes.

Indeed, British attempts during 1942 to reassert C-in-C, WA’s command of convoy operations to WESTOMP were motivated in part by a desire to establish Western Approaches tactical doctrine firmly over the whole of the crucial central segment of the convoy route. Although these considerations may have troubled some officers in the late summer of 1941, they were more than outweighed by the enormous benefit of American assistance in convoy operations in the Western Atlantic. What almost certainly caused Canadian officers consternation (as it did the British) was the division of labour resulting from USN participation in NEF’s area. United States Navy destroyer forces were more suited, tactically, to the escort of fast convoys, where their high speeds allowed them greater flexibility. A corvette detached from a fast convoy for any length of time simply did not have sufficient margin of speed over its charges to regain station in the screen quickly. The different qualities of the two forces were recognized, and on 25 August the RCN agreed to assume responsibility for slow convoys between WESTOMP and MOMP.

(Officers and ratings on the bridge of the destroyer HMCS Restigouche watching a torpedoed Greek-merchant vessel sink, circa 1941.)

Escorting slow mercantile convoys was a calling of dubious distinction. Later, operational research would reveal that ships in slow convoys stood a 30% higher chance of being torpedoed than those in fast convoys. In the summer of 1941 this grim statistic remained to be proved, although it should have been obvious that slow convoys spent nearly 30% more time at sea and this, in combination with their inability to respond to tactical situations, made them much easier targets. It is also clear that to some extent the high loss rate in slow convoys was due to the fact that they were largely escorted by the RCN. It was unfortunate for both that the RCN continued to escort the bulk of slow convoys long after the sleek USN destroyers sailed for warmer climates.

The RCN had settled on St John’s but had earlier considered Botwood, on the island’s north coast, as a possible alternative. Although it seems a remote location, Botwood made more sense operationally in mid-1941 because convoys were being routed through the Straits of Belle Isle, at the opposite end of the island from St John’s. The circuitous routing, problems plaguing new corvettes and the aged four-stackers, weather and sea conditions, and the constant threat of enemy action conspired to give NEF’s early operations a befuddled, occasionally comic quality. One such convoy operation from late August will serve to illustrate the character of those early forays and the trouble the Canadians managed to inflict upon themselves.

In the last week of August the Twenty-first Escort Group was detailed to escort convoy SC-41, scheduled to clear the Straits of Belle Isle on 27 August. Two days before the agreed rendezvous the corvette Galt departed St John’s for Wabana, to escort a small joiner convoy to SC-41. The balance of the Twenty-first Group, the destroyer St Croix, Commander H. Kingsley, RCN, as SOE, and the corvettes Buctouche and Pictou, sailed the next day and made the rendezvous with the convoy on schedule. Relief of local escort, the RN sloop Ranpura and the corvette Matapedia (RCN), was effected without difficulty, but SC-41 was badly scattered among icebergs, which, along with poor visibility, made effective screening impossible. When, by the next day, SC-41 had cleared the ice and fog, it was delayed because Galt and her charges had failed to make their rendezvous. Nor were the two portions of the convoy in radio contact. In the early hours of the twenty-eighth Buctouche was thus engaged, the fog that had once again beset the convoy lifted, revealing that the corvette Pictou was no longer in company. St Croix remained SC-41’s sole escort until Buctouche rejoined, whereupon she was immediately detailed to repeat the exercise, since nothing had yet been heard from Galt.

(An unidentified machine-gunner manning a .50 calibre gun aboard HMCS St Croix at sea, March 1941)

When it was finally clear that Halifax had repeated Buctouche’s message to the errant escort, she returned to SC-41. In the afternoon of the twenty-eighth the convoy received brief air cover before the fog once again closed in. The night passed uneventfully, which was just as well for the two escorts of the screen. Part of the next morning was passed sinking canvas fishing floats, which provided some relief and some gunnery practice. But the highlight of the morning came when pictou rejoined. She had spent most of two days battling a faulty magnetic compass and engine defects. Later, just before hands were piped to dinner and as Buctouche closed with the St Croix to obtain medical supplies for a rating suffering gonorrhoea, Pictou broke down again. Buctouche was detached to stand by, and when it was found that Pictou could only make four knots, she was ordered to return to St John’s alone.

As one player left the stage, another lost soul made a much belated entrance. Galt and her charges, less one, were met before sunset on the twenty-ninth. The missing ship fortunately had not been lost to enemy action. As Galt reported to Kingsley, the motor vessel Odorin believed that she was not required to sail in convoy. When Galt closed to pass orders instructing her to do so, there had been a slight collision. Neither ship suffered damage, but Galt was unsuccessful in forcing the reluctant ship into her station. Rather like a jilted lover, Galt reported that Odorin was last seen in company ‘with a Portuguese.’

On the morning of the thirtieth St Croix’s steam-powered steering developed a leak and she had to revert to manual, at least until a gale struck later in the day, when she effected emergency repairs simply by closing off the space unto which the live steam was escaping. Later, her gyro-compass was knocked out of commission when a rating asleep on a nearby bunk was thrown on to it as his ship was lifted by the heavy sea. The convoy was reassembled following the gale on Monday, September 1st, and the next day an RN Town-class, Ramsay, joined the escort as it sailed into U-boat infested waters. In the days that followed various U-boat contacts were made, but air cover from Iceland kept the balance in the escort’s favour. The only equipment failure to occur before the Twenty-first Group left SC-41 for the Icelandic port of Hvalfjorhur was the asdic of Buctouche. She put her own set out of action by the shock of a depth charge attack, an all too frequent cause of equipment failure on Canadian corvettes.

The passage of SC-41 had all the flavour of NEF convoy operations in 1941: fog, collision, gales, ice, equipment breakdowns, lost escorts, reluctant and ill-disciplined merchant masters, and a small, poorly coordinated escort. All this was bad enough. But when this circus was beset by a pack of determined and skilled U-boats in a part of the ocean far from quick reinforcement, the result was a genuine nightmare. Such was the be the battle of SC-42.

The enemy that NEF faced in late 1941 was its exact opposite in almost every conceivable sense. The U-boat fleet was still an elite force: well motivated, highly skilled, and very professional. To these qualities, the hallmarks of pre-war service, could now be added two years of hard experience in war, experience gained at a time when Allied countermeasures were in the formative stages and mistakes by U-boat captains offered food for thought and learning, not the prospect of certain death. Admittedly, the British had scored great success against the U-boat fleet late in the second winter of the war. In March alone Germany had lost one-fifth of her operational U-boats and her three top U-boat aces: Prien, Schepke, and Kretchmer. These losses proved the wisdom of the convoy and escort system, its value as a strategic offensive. Escorted merchant shipping forced the U-boats to fight in order to fulfill their assignments. At the tactical level the escort’s task, at least until 1943, was to ‘hold’ this strategic objective by waging a defensive battle. This was particularly so in the first four years of the war, when it was the U-boats, as attackers with the initiative, who determined the character of convoy battles.

By 1941, with new U-boats coming into service in increasing numbers and the seas around Britain largely barren of unescorted trade, German tactics finally became highly centralized. Their object now was to mass overwhelming strength against convoyed shipping. Finding and plotting operations against convoys in the broad Atlantic was no mean feat, particularly after the Allies penetrated the German naval ciphers in June. But the requirements of concentrated attack also facilitated coordinated searches over vast stretches of ocean. By disposing a U-boat pack in a patrol line at right angles to the main convoy routes, BdU expected to ensnare a convoy, determine its position, course, and speed, and bring the pack down upon it. Failing the success of initial dispositions, the whole line could be moved in any direction or used to ‘comb’ the convoy lanes in search of targets or convoys which may have slipped through during darkness or bad weather. The longer the line or the greater the number of U-boats, the better the chances of interception and successful attack.

(U-570, a Type VIIC captured by the British in 1941. Type VIICs represented the backbone of the U-boat fleet)

Admiral Donitz had thought through the theory of pack attacks before the war. When he took command of Nazi Germany’s first U-boat flotilla in 1935, Donitz experimented with and perfected his theory. Initially he sought a local means of command and control of pack operations from a specially equipped U-boat. It was soon realized, however, that submarines were unsuited to the task of command. The easy elimination of the directing U-boat, even by an unwitting enemy aircraft or warship which forced it to submerge, made local command of packs impractical. The only alternative was shore-based control through the use of high-frequency, longe-range wireless. Donitz and his officers appreciated that regular or even frequent signalling presented the enemy with potentially useful operational intelligence. To minimize the danger, the Germans developed a system of standardized numerical and alphabetical codes representing regularly used phrases. They also developed high-speed automated transmitters which could send these small groups of figures almost instantly. The likelihood of successful enemy use of the actual signal traffic, (that is, the analysis of volume, location of transmitters, and so on, as opposed to reading the signals themselves) was considered minimal and in any event was outweighed by the practical advantages of central control. Signals were also considered relatively safe from enemy cryptanalysts. They were encoded and deciphered on a mechanical device, resembling a typewriter, the settings of which were changed daily, presenting the potential interloper with an astronomically high number of possible combinations. The germans were not so naive as to believe that the settings, or individual signals, would never be broken. but the time-lag would inevitably prove much too long to affect operations.

The entire system of shore-based control and pack attacks on escorted convoys was tested in exercises immediately before the war and was found to work perfectly. Whether the Allies were aware of these exercises in the Baltic and the Atlantic remains unknown, but the tactics themselves were certainly not a secret. Donitz actually published a book in January 1939 outlining his method of submarine attack on trade. Its adoption in wartime was delayed by the sheer abundance of easy targets in the first year. Perhaps because of this delay, the British expressed surprise at the german adoption of pack attacks in late 1940.

The key to the whole German system was, of course, use of wireless. In general U-boats observed strict wireless silence, but the instances in which they were called upon to communicate with BdU were numerous. Daily position reports were usually required of U-boats on station in a patrol line, and occasionally BdU wanted weather reports as well. U-boats were naturally charged with reporting major enemy naval units and all convoys, along with details of position, course, and speed. In a pack operation against a convoy the first U-boat to intercept was directed to act as a shadower, maintaining contact and sending off periodic reports (on average, every two hours). Based on the intelligence provided by the shadower, BdU directed other members of the pack on to the convoy. In addition, BdU could also instruct the shadower to transmit periodic homing signals on medium frequency for the benefit of U-boats trying to join in.

Modifications to this system were made from time to time, such as allowing the shadower to attack, or holding off all the U-boats in contact until a large force was assembled. But the basic principles of central control, concentration, and (whenever possible) mass attack remained unaltered until late 1943. BdU’s control of all phases, with one exception, was absolute. The exception was the actual attack itself. BdU gave permission for U-boats to launch attacks, but each commander then acted independently. Tactical coordination would have reaped handsome rewards, and the Allies frequently attributed German succes to such coordination. In practice, however, the physical limitations of a Second World War submarine and the difficulties of attacking a seething mass of ships in the dark of night made coordination at the local level impossible. U-boat wolf-pack tactics therefore had an apt appellation. On the long lead of wireless, BdU tightly controlled its packs until the signal to attack was given. From then until a night’s action was over and the pack needed to be concentrated for another assault, the U-boats were turned loose on the convoy. Canadian escorts had brushed with this enemy before, and of course NEF had been blooded by a pack as early as June. But the battle of SC-42 in September revealed that NEF was a very long way from having the measure of its enemy, a situation not peculiar to the RCN.

Aside from its obvious significance as a major convoy battle, the story of SC-42 is important for two other reasons. The two nights during which NEF Group Twenty-four fought alone were the acid test of the expansion fleet, and the fleet failed. The reasons for its failure have been touched upon, but it is necessary to illustrate just how these shortcomings manifested themselves in the face of the enemy. The other matter of significance will be touched upon in a special I am going to write about SC-42. A stand alone post relating the battle as it unfolded.