DISCLAIMER: The vast majority of this information is either directly quoted from the sources below or only slightly changed. Very little of it is my original thoughts, save a paragraph here or there. I attribute the following completely to my sources and make no claims otherwise. If so desired I will remove this content from the website without hesitation if asked to do so by TIMEGHOST or by any of the original copyright holders. My intent is purely the sharing of historical knowledge regarding Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic.

Sources:

“The Far Distant Ships” by Joseph Schull, ISBN-10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

“North Atlantic Run” by Marc Milner, ISBN-10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Joseph Schull’s work, published 1985)

“Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War: Volumes 1 & 2” ISBN-10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

Early-to-mid 1941,The Rocky Isle in the Ocean, The Newfoundland Escort Force, Canadian Corvettes, Chummy Prentice"

The issue of providing start-to-finish escort was discussed by the British and Canadians over the winter. These talks were the first sure indication that RCN corvettes were likely to be used as ocean escorts (what the navy thought corvettes earmarked for the eastern Atlantic were going to be doing otherwise was anyone’s guess). In any event, the Anglo-Canadian discussions identified three factors crucial to the establishment of end-to-end coverage: the escorts must be available; they must have reached a reasonable state of individual and escort-group training, and the necessary bases must be available. In May 1941 none of these factors existed in the Western Atlantic. An insufficient number of new corvettes were in commission and most of these only recently. The development of facilities was now top priority, but support facilities outside of Halifax were non-existent, and the standard of training was inadequate to say the least.

Here enters my home province. The natural place from which to stage escort operations in the Northwest Atlantic was the island of Newfoundland. To briefly discuss Newfoundland’s role so far, when Canada declared war on September 10th, Newfoundland had already been at war seven days. As a British colony ten years removed from Confederation, the mainland declaration of war received modest space on page four of the St. John’s Evening Telegram newspaper. They had participated in the first “hostile” act in North America: a German merchant vessel had been seized and thirty prisoners taken. The local YMCA was converted into a prison. Rationing and dim-outs took effect instantly. Wireless telephones and private radio stations were silenced, mail and cables censored, aliens registered and controlled. Insurance premiums on waterfront property had gone up in less than a week from $1 to 5$ for each $1000 of coverage.

(View of St John’s harbour entrance and port facilities. A minesweeper is leaving port. Taken from Signal hill, 1942)

Although not part of the Dominion of Canada, the island was integral to Canadian defence, and its protection was assumed, in consultation with the British, as a Dominion responsibility in 1939. By early 1941, however, the Canadian armed forces had made only a modest contribution to its defence. The navy had also seconded personnel to the Naval Officer in Charge, St John’s, Captain C.M.R. Schwerdt, RN, the only naval establishment on the island. Until the latter was turned over to the RCN in early May 1941, the Canadian Navy had no permanent presence in Newfoundland. For a number of reasons, not all of them enemy inspired, this low level of activity was destined to change. the absorption of Schwerdt’s command into the RCN came as part of the integration of Newfoundland into the Canadian east-coast command system, and it mirrored similar army and airforce arrangements.

But Canada was also engaged in an embryonic war of influence with the U.S. over the old colony. The establishment of American bases on the island, as a result of the destroyers-for-bases deal with the British, was attended by an agreement granting the U.S. rights to defend its new bases by operations in adjacent territory. The agreement was concluded despite strong protests from Canada and in spite of the prior Canadian claim to Newfoundland defence.

The anxiety Canada felt over her position in Newfoundland was exacerbated by joint Anglo-American planning of a combined strategy for the defeat of Germany should the U.S. enter the war. For several weeks in early 1941 senior American and British staffs met in Washington to discuss a co-ordinated Commonwealth and U.S. plan. neither Canada nor any of the Dominions was accorded official representation, although British delegates kept their commonwealth allies informed of proceedings. The result of these meetings was an agreement, American-British Conversations 1 (ABC 1), whereby the world was divided into two basic strategic zones. The Americans were to assume responsibility for most of the Pacific and for the Western Atlantic, with the exception of waters and territory assigned to Canada ‘as may be defined in United States-Canada joint agreements.’

The Canadians were not pleased with their treatment in the Anglo-American discussions, and the Chiefs of Staff feared that ABC 1 was intended to oust them from Newfoundland. The issue was somewhat problematical, since the implementation of ABC 1 was dependent upon U.S. entry into the war. However, the resolution of such issues, which had a direct bearing on Canada’s responsibilities as a sovereign state, did not accord with the national view of Canada as a full and independent partner in the war against Germany. Canada was already attempting to force recognition of that claim, at least with respect to North American defence, by the establishment of a Canadian Staff mission to Washington. While the battle to be heard and recognized went on, Canadian responsibilities under under the terms of ABC 1 were worked out by the Permanent Joint Defence Board. These agreements, styled ABC 22 and appended to ABC 1, gave Canada responsibility for her own coastal waters (three miles) and for the commitment of five destroyers and fifteen corvettes to U.S. Navy forces in the Western Atlantic. Under the terms of ABC 22 the balance of Canadian naval forces was to be sent overseas.

(The members of the Permanent Joint US-Canadian Defence Board in August 1940)

In the strictest sense, should the U.S. enter the war, Canada had lost the battle for Newfoundland. But though the Canadians had earlier been prepared to place their forces unreservedly under U.S. strategic direction in the worst-case scenario of Plan Black, they considered ABC 1 and ABC 22 offensive plans. The Canadians therefore clung firmly to their right to exercise command and control of Canadian forces in Canada and Newfoundland, even should ABC 1 come into force. Further, actual command of forces, despite a strong American sentiment to the contrary, was to remain with the respective nations. Coordination of the military effort in a given area was to be by ‘mutual cooperation.’ Unified command of all forces under a single officer was allowed for upon agreement by the officers in the field or the Chiefs of Staff. The criteria for determining who was to command under such conditions were never clearly defined; however, the Canadians at least considered that the size of national contingent and the rank and seniority of its commanding officer were governing elements. It was Canadian practice, therefore, throughout the joint American-Canadian occupation of Newfoundland to keep Canadian strength above that committed by the U.S. and to ensure that the senior Canadian present outranked his American counterpart. All of these considerations were foremost in the minds of the Canadian government and Staffs when Canada was asked by the British to base large escort forces at St John’s in the spring of 1941.

Thus, aside from the very real operational importance of the task, it was not surprising that the RCN responded enthusiastically to the Admiralty’s request of the 20th of May that the navy begin the escort of convoys from a base at St John’s. NSHQ responded by declaring that it was prepared to commit all of its new construction and its destroyer forces as well (virtually the whole navy). “We should be glad,” the Canadian reply read, “to undertake anti-submarine convoy escort in the Newfoundland focal area.” Naturally, command of the forces would rest with an RCN officer, and NSHQ suggested Commander E.R. Mainguy, RCN, commander of HMCS Ottawa ,an officer with experience in the Western Approaches who would be promoted to Captain for the task. (He would not receive this post but would continue to fight in the Battle of the Atlantic). The Canadians agreed that the Admiralty, through the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches (C-in-C, WA), would assume ‘direction of this force when necessary to coordinate its cooperation with those of the Iceland force.’

(Commander E.R. Mainguy, Captain of HMCS Ottawa, off Botwood, Nfld. June 1940. Botwood was being scouted as a potential seaplane base at the time, and would eventually become home to two RCAF Canso Squadrons and a full Canadian Army detachment.)

Whether Canadian enthusiasm for the Newfoundland Escort Force (NEF) stemmed from a belief that a permanent, military and politically acceptable role for the burgeoning corvette fleet had been found remains a mystery. What is patently clear, however, is that both the British and the Americans considered the NEF a stopgap measure. By the summer of 1941 it was becoming increasingly evident that the U.S. would get involved in the Atlantic battle under the guise of defending the neutrality of the Western Hemisphere. When that happened, the role of the RCN in the Western Atlantic would be governed by the accords of ABC 1. Whatever the final outcome of NEF, the commitment of the corvette fleet to ocean escort work marked a radical departure from the intended use of such vessels.

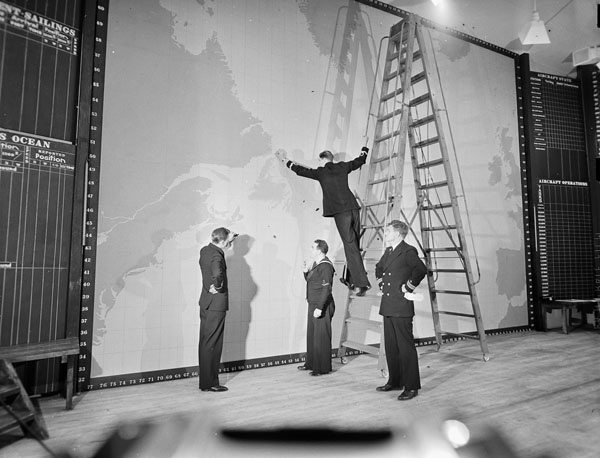

(Royal Canadian Navy Operations Room, St. John’s, Newfoundland, 24 September 1942.)

Returning to the corvettes themselves for a moment, while I have already spoken of the diversity of the modifications that they would receive, it is important to discuss the modifications that Canadians would give to their own corvettes in comparison to RN ones. The RN had used its corvettes for ocean escort from the outset and had begun some of the piecemeal modification of the class to make the vessels more suitable for work on the open sea. The lengthed forecastle increased crew space and made the ships drier. The bows were also strengthened to take the pounding of the heavy seas. Corvettes of the first Canadian construction program, already delayed, might well have incorporated these changes while the ships were still in the builder’s hands. Yet those being built for the RCN went ahead largely as originally planned. The major Canadian alteration of the original design reflected the corvette’s inshore and ‘Jack-of-all-trades’ role, the aforementioned minesweeping gear. This involved considerable alteration of the quarter-deck, cutting back the engine-room casing to accommodate the steam winch, broadening the stern to fit both fairleads for the 'sweep wires and the depth charge rails, and the addition of storage for the 'sweep gear.

All of this delayed completion and may have hardened the Staff to any further delays occasioned by major alterations. Moreover, that the Naval Staff was not unduly concerned about the ASW performance of the corvettes is evidenced by the fact that the addition of a full minesweeping kit ‘had an adverse effect on the operations of the ASW gear.’

The latter, as the Staff went on to observe, was carried forward and was affected by the corvette’s tendency to trim by the stern when fitted for minesweeping. In practice, however, the original corvette design, when fully stored and armed, tended to trim by the bows, which also affected ASW efficiency. The addition of extra weight in the stern may unwittingly have compensated for the design fault. More important in terms of seakeeping and habitability in deep-sea operations was the forecastle extension adopted by the RN. News of this modification reached NSHQ while most of the first corvettes for Canada were still in the builders hands. Although the RCN would make allowances for more crewmen, better refrigeration, a more powerful wireless set, and more depth charges, the navy did not act on this fundamental alteration in basic structure until after sixty of their own corvettes had been built, much later in the war.

The Staff would recognize the value of the design improvements. These were to be embodied in a new class of corvette, the Revised Patrol Vessel (RPV), which was much better suited to deep-sea operations. The RCN ordered ten RPVs in early 1941, and all were in commission by the spring of 1942. Unfortunately, it took some time for these purpose-built ocean escorts to find their way into mid-Atlantic operations. In the meantime, the navy plodded along with ships that, by early 1941, the navy still considered in-shore auxiliaries. Indeed, at NSHQ the corvettes were still tied closely to the defended-port system under Plan Black. It is also arguable that the Staff’s failure to extend the forecastles of corvettes when it had the chance stemmed from the navy’s desire for as many ships as could be acquired to permit expansion to really get going, or from the increasing gravity of the war at sea. It was a lost opportunity that would come to haunt the navy and the corvette crews.

The forecastle extension (or lack thereof) would come to be the norm for the RCN and NSHQ. Certain trivial modifications seemingly at random, major ones delayed exponentially. The after gun platform (for the Pom-Pom) was moved further to the rear of the ship so that it was not in danger of blowing away the mainmast, and would remain further to the rear long after the secondary mast was discarded. Shortage of primary Triple A armament saw a number of .5-inch Colt and Browning machine guns acquired from the U.S. and fitted in twin mounts (two in the aft gun position and one twin-mount on either side of the bridge). Inability to acquire .5-inch saw the return of the Lewis guns. Both were virtually useless.

Other changes between RN and RCN corvettes were less noticeable, but had a marked effect on performance. There was no provision for a breakwater on the forecastle of original corvettes. Without them, water was able to run aft and pour into the open welldeck (the crews main thoroughfare). The British soon fixed this, but the RCN would move with incredible slowness on the matter, making RCN corvettes unnecessarily wet. Canadian ships were often completed without wooden planking or some form of synthetic deck covering to prevent slipping in the waist of the ship, where the depth-charge throwers were fitted. Since this area was also constantly wet, the difficulties of loading live charges can be imagined.

The most telling shortcoming of Canadian corvettes, and the one that was to cause the greatest difficulty, was the lack of gyro-compasses. The latter were at a premium in Canada, so the Naval Staff decided to fit them to Bangor-minesweepers, whose need for accurate navigation was paramount. The first Canadian-built corvettes were equipped with a single magnetic compass and the most basic of asdic, the type 123A. Even by 1939 standards the 123A was obsolete and in the RN was considered only suited to trawlers and lesser vessels. The 123A’s standard compass, graduated in ‘points’ and not in degrees, made it equally hard for captains to coordinate operations between two ships or to undertake accurate submarine hunts and depth-charge attacks. The single binnacle and its attendant trace recorder were mounted in a small hut, above the wheelhouse. During an action it was impossible for a captain to be both in the asdic hut and outside on the bridge wings, the only place from which he could obtain an overall perspective on the situation. Nor was the needle of the standard compass properly stabilized, a deficiency particularly noteworthy in such “lively” ships as corvettes. As a final depressing point, it should be noted that compasses were also susceptible to malfunction from the shock of firing the main armament, exploding depth charges, or simply from the pounding of the waves. The tendency of Canadians to launch inaccurate depth charge attacks proved a continuous source of criticism from British officers.

(Officers on the open bridge of HMCS Trillium, a Flower-class corvette.)

Partly because of a disparity of resources, partly because there was still a lot of ambiguity concerning the role that the corvettes and the RCN would play in the war in general, the RN corvettes outclassed RCN corvettes when it came to performance on the open sea. Misapplication of Staff energies also played a role. Instead of laying down a basic policy for the engineer-in-chief to follow, the Staff would haggle over every conceivable alteration to their corvettes. Incline tests were to be done before the .5-inch machine guns were authorized for the bridge wings, even though they knew full well that the British had already adopted the same practice. Had the RCN stuck to a distinctive class name, instead of adopting the British class name of 'Flower" to its corvettes, the tremendous differences which were to prove so very important by 1942-43, might have been as apparent as they were real.

( A sheet of sea water splashes over a crew member of HMCS Trillium, September 1943.)

NSHQ’s notion that the RCN was to provide convoy escorts for the Newfoundland focal area suggests that the Naval Staff had not made the mental leap from the concept of locally based ‘strike forces’ to the idea of a regional escort force. In this they were not alone. The distinction between two types of operation, offensive and defensive, was never very clearly drawn. The NEF was, nonetheless, admirably suited to RCN capabilities. It also met the geopolitical aspirations of the government whilst being vital to the war effort. So far, so good.

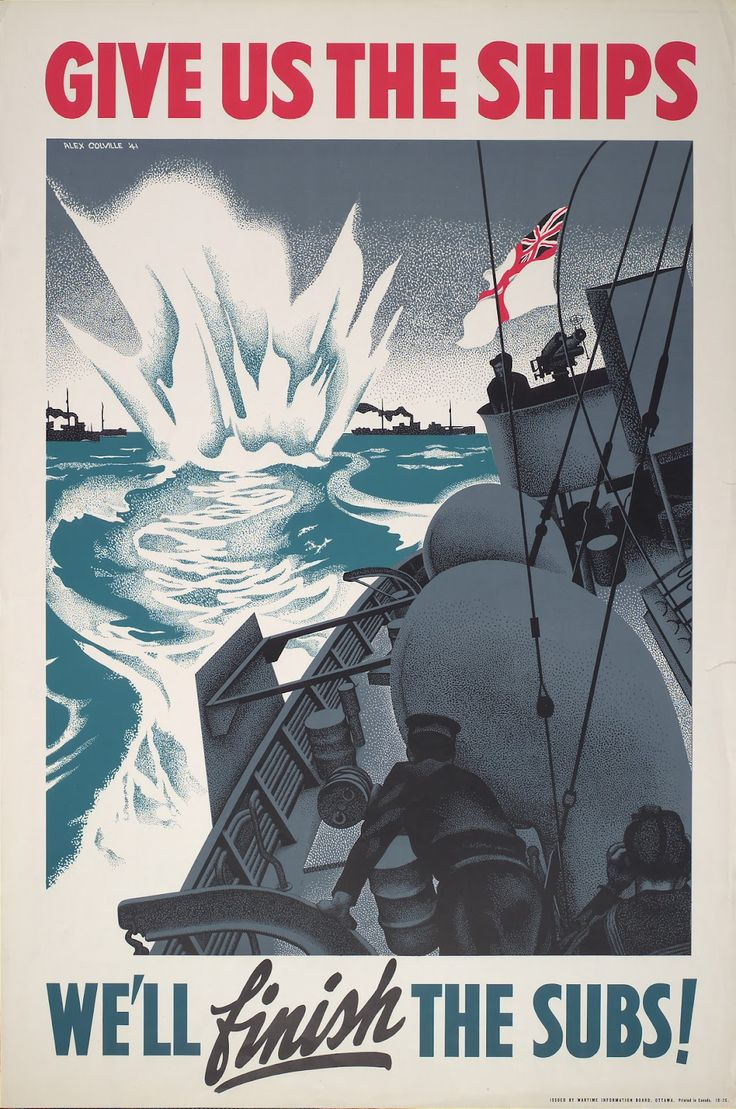

The war was entering what Churchill called “one of the great climacterics.” On June 22nd, Hitler would invade Russia and soon had her reeling. A Soviet collapse would give Hitler access to enormous resources. Even if Russia could fight them to a stalemate, there could be no Allied victory without an attack supplied by sea and mounted from the British Isles. Whether for the ultimate defence against a stronger Germany or for our own seaborne assault, Allied resources had to be turned into munitions of war and stockpiled in the UK. The resources were more than sufficient, but between the promise of the future and the need of the present lay a perilous gap of space and time that could only be bridged by ships, all the ships now available and hundreds more. Many convoys arrived at British ports each week and the tonnage unloaded was enormous. Yet a great percentage of it was what the island required simply to exist. Only the margin above that daily necessity represented the power to wage war. Munitions, aircraft, guns, tanks, and above all, aviation gasoline and fuel oil. If oil stocks fell below the point of safety, the operation of ships and planes would have to be curtailed. If U-boat attacks could not be met effectively, more ships would be lost, creating further shortages which would again reduce operations. The increasing demands of the war had to be met by a corresponding increase in the flow of cargo.

The U-boats imposed a steady drain. Three merchant ships were going down for every one replaced. Eight submarines were coming into operation for every one sunk. U-boats swarmed in the Mediterranean. They were off Gibraltar, off the Cape Verde Islands at the bulge of Africa, off Cape Town far to the south. By the virtue of St John’s position alone, it bridged nearly a quarter of the gap between the Canadian seaboard and Iceland. June 1941 would also see Canada’s Commodore Murray return from Britain to become Commodore Commanding Newfoundland Escort Force. From Liverpool, the RN’s Commander-in-Chief Western Approaches, Adm Sir Percy Noble, directed the whole Atlantic battle, but Commodore Murray exercised autonomy within his own war zone. The Newfoundland Force was made up of six Canadian destroyers and seventeen corvettes, plus seven destroyers, three sloops and five corvettes of the RN. Soon more ships, French, Norwegian, Polish, Belgian and Dutch, were allotted to Commodore Murray. His authority extended to all local escorts operating from St. John’s and to convoys and their escorts while in Newfoundland waters.

(S.S. Rose Castle sinking, October 1942)

One of the most colourful men to serve in the Newfoundland Escort Force was Comdr. J.D. Prentice. He had taken early retirement from the RN in 1934 to manage his ranch in British Columbia. In 1939, at 41, he returned to sea. “Chummy” Prentice, as his friends called him, was one of the real characters of the war and a driving force behind the RCN’s quest for efficiency. Born in Victoria, BC, of British parents in 1899. His twenty-two years of service in the RN had been undistinguished, the pinnacle had been rising to the rank of First Lieutenant Commander of the battleship Rodney. When passed over for promotion in 1934, Prentice felt he had gone as far as he could go, opting for the aforementioned early retirement.

The RN having no immediate employment for him in 1939, he was placed on the list officers at the disposal of the RCN. When the RCN mobilized, Prentice was offered a commission at his old RN rank. An offer he eagerly accepted. He was posted briefly to Sydney, NS as staff officer to the Naval Officer in Charge. Although by all accounts he was content with this, he was removed from this posting and transferred to Halifax to await the commissioning of the corvette Levis, which he was to command. Whilst stationed in Halifax, he came into contact with Commodore Murray, then Commodore Commanding of the Halifax force, whom he had met at the RN staff college years before. The two men shared many ideas and interests, and became fast and lifelong friends. Prentice soon found himself attached to Murray’s staff as Senior Officer, Canadian Corvettes. It was a curious post, one which never fit into the organizational structure of any command and soon became little more than titular. However, it did provide Prentice with a legitimate priority of interest in the affairs of the little ships, which he was to exercise consistently over the next three years. Murray and Prentice would be separated when Murray left for Britain to take command of Canadian vessels overseas through the summer of 1940, and Prentice would spend the winter of 1940-41 working up what few Canadian corvettes had been launched before the freeze up. What was to become “The Dynamic Duo” of the east coast was not to be broken up for long. March 1941 saw Prentice finally given his first command, HMCS Chambly.

All of this gave his fertile and often over-active imagination an opportunity for expression, for Prentice was an innovator and an original thinker. During his service in the RN he had produced numerous papers and essays for publication and competitions on a myriad of topics. Not surprisingly, he quickly developed ideas of what corvettes were capable of, how they could be used, and how their efficiency could be improved

As a senior officer in a rather junior service with which he had no long-standing presence or long-term ambitions, Prentice allowed his concern for efficiency to dominate his work. His combination of experience, seniority, and lack of vested service interest gave Prentice a freedom of expression which few if any other RCN officers enjoyed. By all accounts he used his position and influence wisely. In any event, Murray was always interposed between Prentice and more senior (and possibly less tolerant) officers and was therefore able to direct some of the heat generated by Prentice into more useful, if not always successful, directions. In many ways Prentice was Murray’s alter ego, an energetic innovator paired to an efficient but somewhat uninspired administrator. Prentice’s eccentricities apparently did not keep him at arm’s length from his fellow officers. More importantly, perhaps, his cigars, monocle, English accent, and sense of fairness positively endeared him to the lower decks. The story of the monocle is probably apocryphal, but it illustrates the type of rapport he apparently had with the other ranks. It is said that once a whole division of Chambly’s company paraded wearing monocles. Without saying a word or altering his expression Prentice completed his rounds, stood at the front of the assembled men, and, instead of the dressing down the men expected, Prentice threw his head back, flinging his monocle into the air. As the glass fell back he caught it between his eyebrow and the bottom lid, exactly in the place from whence it had been ejected. “When you can do that,” Prentice is reported to have said, “you can all wear monocles.” True or not, it makes the point. He was fair, had a good sense of propriety, and above all else, enthusiastic about his work, which seemed to rub off on those who came in contact with him. Whilst the RN apparently felt he had little to offer them, Prentice had found his calling with the small ships of the RCN.

Prentice was an ideal commanding officer and admirably suited for the posts which he held. He was ruthless in his quest for efficiency at all levels of shipboard life, from gunnery to the welfare of the lower decks.“The enemy,” he told his officers, “is not destroyed by untrained ships.” He proceeded to ensure that Chambly was a trained ship. The first task assigned to Prentice and the young NEF was screening the battle-cruiser Repulse as she lay in Conception Bay following the hunt for the Bismarck. It was good basic exercise if nothing else, and the clear, unstratified waters of the bay returned good asdic echoes. The real work was to begin shortly thereafter.

(Commander J.D. Prentice, Commanding Officer, on the bridge of HMCS Chambly at sea, May 24th 1941)

Pending the arrival of a Canadian commanding officer for the NEF, the escorts were placed under Captain Schwerdt, RN, the Naval Officer in Charge, St John’s (whose establishment had only just been transferred to the RCN). Schwerdt, in consultation with his trade officers, determined that NEF should attempt its first escort of an eastbound convoy in early June. The date of sailing, course, and so on could all be obtained through local trade connections, and a rendezvous with HX-129 was worked out by Schwerdt’s staff. Word-of-mouth orders were passed to Prentice advising him of this plan and of the likelihood of very poor weather. The orders, which in effect stated ‘If you have any reasonable hope of joining the convoy, proceed to sea.’ gave Prentice the carte blanche he thrived on; foul weather only added to the challenge.

(Members of the Ship’s Company, HMCS Chambly, St. John’s Nfld. May 1941)

On June 2nd, the first NEF escort group to sail on convoy duty put to sea. The escorts Chambly, Orillia, and Collingwood rendezvoused with HX-129 within an hour of their estimated position. Although the convoy was not attacked, many stragglers and independents nearby were lost to enemy action, and the Canadians soon found themselves busy with rescue work. Two asdic contacts were made. One each by Collingwood and Chambly while operating in company. Unfortunately, coordination of searches was hampered by the failure of visual-signaling equipment aboard Chambly. The latter also had to stop engines twice to repair defects. Despite the breakdowns, lost opportunities, and general mayhem of this first operation, Prentice’s spirits were extremely buoyant.

“The ships behaved extremely well,” he wrote in his report of proceedings. Certainly all the COs in question, Acting Lieutenant Commanders Briggs and Woods, both RCNR, went on to do well in the RCN. But one cannot help but feel that Prentice was writing about the ships themselves. The first operation of the NEF pointed to the many problems which beset the expansion fleet, and yet Prentice was pleased with the group’s performance. Having participated directly in the commission and workup of the first RCN corvettes, the Senior Officer, Canadian Corvettes, could be excused his pride in their initial foray into troubled waters. Other RCN officers maintained similar limited expectations of the expansion fleet. The British, on the other hand, entertained little sympathy for struggling civilian sailors. From the outset, RCN and RN officers displayed a tendency to view the expansion fleet from vastly different perspectives. To use an analogy, the RCN was, through the period of 1941-43, like half a glass of water. From the Canadian perspective the glass was half full; the RN always considered it half empty. Though the Naval Staff was apparently informed of how ill prepared the early corvettes really were, this came as a rude shock to the more staid RN. Moreover, shortcomings manifested themselves even before the first major Canadian convoy battle.

(R. Cosburn and Lieutenant F.A. Beck (right) at the asdic set on the bridge of HMCS Battleford, Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada, November 1941.)