DISCLAIMER: The vast majority of this information is either directly quoted from the sources below or only slightly changed. Very little of it is my original thoughts, save a paragraph here or there. I attribute the following completely to my sources and make no claims otherwise. If so desired I will remove this content from the website without hesitation if asked to do so by TIMEGHOST or by any of the original copyright holders. My intent is purely the sharing of historical knowledge regarding Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic.

Sources:

“The Far Distant Ships” by Joseph Schull, ISBN-10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

“North Atlantic Run” by Marc Milner, ISBN-10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Joseph Schull’s work, published 1985)

“Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2” ISBN-10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

1940: The Fall of France, The Battle begins, the RCN dreams of expansion

Continued from The Far Distant Ships…

A week later all four RCN destroyers joined the RN force fending off U-boats and E-boats and salvaging the melancholy remnants of defeat as German infantry and armor poured into France. Restigouche and St. Laurent, on June 9th, saw from 30 miles out the flames of Le Havre rising 600 feet into the night sky. On June 11 they were off St. Valery-en-Caux near Dieppe, helping a British destroyer embark wounded. Part of the British 51st Division as holding a six-mile line in the vicinity but reported itself “in no immediate need of evacuation.” About 8:00 AM on the 12th five salvos splashed into the water 100 yards from St. Laurent and Restigouche. A German battery had taken up position on the cliffs behind St. Valery. The destroyers engaged the battery, but were unable to observe the fall of their shells behind the cliff. For the first time, Canadian ships had exchanged fire with an enemy…"

Undoubtedly the later alteration of the government desire to keep the destroyers close owed something to the stationing at Halifax of the RN’s Third Battle Squadron, a force of aged battleships and light cruisers intended to provide anti-raider protection for mercantile convoys and more than sufficient to guarantee a credible deterrence along Canada’s Atlantic coast. The government’s change of heart not only suited the navy’s burning desire to join in on the ‘active operations’ of more distant waters but was also perhaps a response to growing public pressure for a more active involvement in the war. In April 1940, before the invasion of Norway began, Mackenzie King confessed to his diary that the pride of the nation demanded that Canada increase its military commitment overseas from a division to a full corps. The slow expansion of the navy could not keep up with the national desire to pick up where the Canadian Corps had left off in 1918. Even Colonel Ralston, the minister of Defence, confessed that the military involvement in the land war would have to grow, although he felt the money would have been spent much more effectively on the air force and navy. The prime ministers private secretary wrote years later that “the vast majority of the Canadian people were still very much removed from the war until the army landed in Sicily in 1943, despite the vast numbers of airmen and sailors who were involved in combat operations.”

On June 21st, the day of France’s surrender at Compiegne, Fraser was sent far down the west coast near the Franco-Spanish frontier, to land a Royal Navy evacuation party and to patrol off St. jean-de-Luz, one of the last remaining exits from France (Operation Ariel, the evacuations from the west coast of France). At dawn on the 23rd she was ordered 90 miles north to Arcachon to pick up some diplomats. Transferring them from the sardine fishing boat they had escaped in was no easy task, but eventually all were delivered safely aboard and then to the RN cruiser Galatea for transport back to England. Fraser returned to St. Jean-de-Luz and was joined by Restigouche and several British destroyers. The tumult of evacuation was fully underway. Boatloads of defeated soldiers and destitute civilians streamed out to liners, tramps, trawlers and pleasure craft, jostling in the rough waters of the harbour. Some destroyers threaded dangerously among the merchant ships, marshaling them unto convoys for escort to England. Other destroyers zigzagged outside on anti-submarine patrol. In the dreary 48 hours of the St. Jean-de-Luz evacuation 16,000 soldiers escaped.

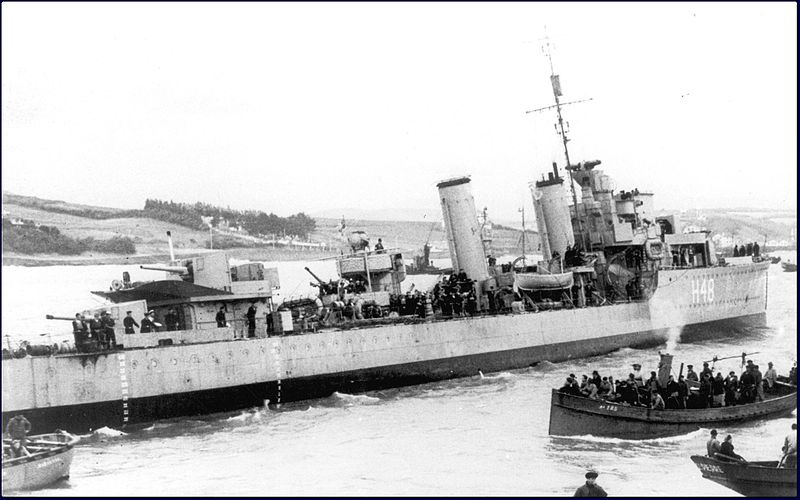

(Photo of HMCS Fraser, commanded by Comdr. W.B. Creery, taken the 25th of June, 1940 off St. Jean-de-Luz.)

Rear Admiral W.B. Creery, at the time commanding officer of the Fraser would describe the final evacuation to Readers Digest years later:

"The Germans occupied Bordeaux and swept south. By the morning of June 25th, they were within 25 miles of St. Jean-de-Luz. The French, to conform to the armistice terms, had advised that all evacuation must cease by 1 p.m. Fraser had been ordered to remain in harbour during the final evacuation but we had difficulty finding a safe anchorage. We had to re-anchor twice. on the last attempt we held firm- for a reason we were not to discover until later. We decided to remain where we were until the return of Sub-lieutenant William Landymore who had been sent away in our motorboat to try and persuade some Belgian trawler skippers to sail to England instead of Spain. Suddenly the officer of the watch, who had a slight stammer, exclaimed “G-G-Good G-G-God, there’s a g-g-gun!” I looked where he was pointing. On a hill a small force of soldiers had appeared with a field gun and a tank. We couldn’t make out their nationality, but ships in harbour are sitting ducks and there was only one thing to do. We ordered the merchant ships to proceed to sea and had to watch several boatloads of evacuees turn sadly back to shore. Our motorboat returned and Landymore sent the boat’s crew swarming up the falls but remained in the boat himself. I was anxious to go to action stations and weigh anchor but it took all hands to hoist the boat. All was going reasonably well until a steadying line parted, the boat canted sharply outboard and Landymore was catapulted into the sea. Just as this happened I was told the anchor had apparently fouled a cable on the bottom of the harbour and could not be hoisted. And the officer of the watch reported that there were now “a number” of field guns on the hill and they appeared to be taking aim at us. So we fished Landymore out of the sea, slipped our cable and departed in haste if not in dignity. The merchant ships headed for England, escorted by several RN destroyers. Fraser and Restigouche were ordered to join the British cruiser Calcutta in a sweep north in search of an enemy ship of which there had been a vague report. No such ship was found and toward dusk the flag officer turned his small force toward home.

Joseph Schull continues this particular narrative in his own book:

" At 10 p.m., with a fresh breeze blowing, a moderate swell and visibility of one and a half miles, Fraser was slightly ahead of Calcutta and to her right, Restigouche a bit behind the cruiser and to her left. They had been in action for a week, under threat of submarine and air attack. Creery had had one nights sleep in ten. Calcutta signaled “single line ahead”: the two destroyers were to form up behind her. Fraser swung left, intending to make a 180-degree turn and run back along the right of the cruiser and come into station behind her. But Calcutta thought Fraser intended to cross in front of her and pass down her left side. Fraser would had had little room to cross in front so Calcutta made a sharp turn to the right, thinking to avoid collision. But the cruisers right turn and the destroyers left had put them, at a combined speed of 34 knots, on courses that made collision inevitable. Engines were put astern and wheels reversed but no order could take effect in time. Calcutta sheared through Fraser. The destroyer’s forepart broke off and floated away. Her bridge, with the bridge personnel, was lifted onto Calcutta’s bow and remained there, swaying and groaning. " The eight of us," said Creery, "hastily climbed over the front screen of Fraser’s erstwhile bridge and dropped six feet or so onto Calcutta’s deck. It was pitch-dark and I couldn’t see any part of Fraser but I heard shouts from the forepart and then, a little later, voices singing ‘Roll Out the Barrel.’ A large portion of the ship’s company had been in their hammocks when Calcutta’s bow plowed through the messdecks. Some must have been killed outright but those who survived found their way up onto the forecastle and were rescued by boats from Calcutta and Restigouche before the forecastle finally filled and sank. Restigouche herself raced alongside Fraser and, rocking in a swell which threatened to dash her against the jagged steel, brought her stern around. While the hulls of the two ships ground perilously together, 60 of Frasers crew, including one stretcher case, were transferred. For the men in the water, Restigouche and Calcutta lowered boats, floats and scramble. Sixteen officers and 134 men were rescued; 47 Canadians and 19 British sailors died. The first RCN sailors to die overseas.

HMCS RESTIGOUCHE, River Class Destroyer. May, 1942

The loss of Fraser, heavy blow though it was, was a minor incident of those disastrous days, one of the casualties as certain to occur under conditions of prolonged and incessant strain as under direct shellfire. Nor could it be lingered upon. Not only was Britain now standing alone in Europe, the supply lines on which her life depended were now imperiled. Skeena, Restigouche and St. Laurent now turned with scores of British ships to a desperate battle for convoy routes through the southwestern approaches to England. The U-boats moved in, and the Luftwaffe was everywhere over the channel and farther out to sea with new bases in France. The great ports of the south and east were within easy striking distance. In their hours in harbour between U-boat hunts, anti-invasion maneuvers, and rescue of survivors from sunken vessels, the Canadian destroyers landed men to help the British during air raids. By early July the hard necessity of revising the whole supply system was conceded. The southern and eastern ports were out of action as far as convoys were concerned. There remained only the ports on the Mersey and Clyde rivers. Cargoes from North America must be landed in the west and north. The great ocean convoys must be sent up through the northwestern approaches. And where the retreating convoys went, the escort vessels followed. The remaining three Canadian destroyers headed north to operate from Liverpool, Greenock, Rosyth and later Londonderry.

Despite the calamity that had occured on the continent, and the desperate Battle for Britain that followed,the first 10 months of the war at sea developed mostly as Allied planners had anticipated. From September 3rd to the Fall of France, Germany’s U-boat fleet was small and remained so. Its operational strength of forty-six submarines (only twenty-two of which were suited to deep sea work) was far short of the three hundred U-boats that Rear Admiral Karl Donitz, (Befehlshaber der U-boote, BdU), estimated he needed to sever Britain’s supply lines. Moreover, the U-boat fleet was initially circumscribed by Allied control of the exits from the North Sea. In the early months of the war U-boat captains generally obeyed their strict instructions not to anger neutral opinion through rash and illegal acts, despite their torpedoing of the liner Athenia on the first day of the war, which suggested that Germany would again adopt unrestricted submarine warfare. So the Allies concentrated on Germany’s surface fleet, on her commerce raiders lurking in disguise on the oceans of the world, and on hapless offensive anti-submarine (A/S) sweeps. The convoys existed and had escorts, but the U-boat was not yet operating at its full potential (as would become evident in late summer), and the escorts were not yet hard pressed.

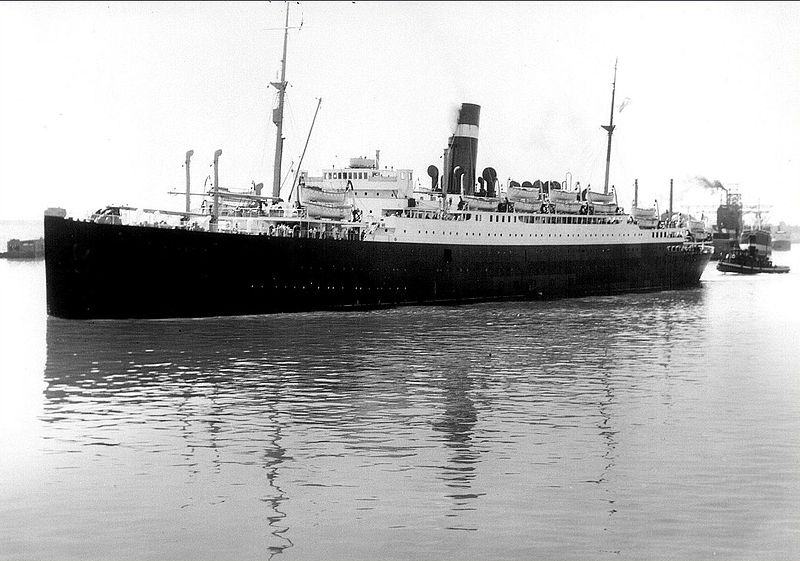

(The liner Athenia in Montreal Harbour in 1933, torpedoed on the very first day of World War 2 by U-30)

As spring turned to summer and through early summer, the few U-boats there were operated mainly between Britain and Iceland. Whilst they achieved nothing too spectacular in terms of tonnage sunk, the few escorts there scored few victories in return. In one three hour hunt St. Laurent and the RN destroyer Viscount dropped 80 depth charges; when diesel oil bubbled to the surface they were sure they had gotten a kill. The Admiralty, cautious to award kills even in the early days, credited them with a “probable.”

The fact that Germany could now make good use of excellent new bases in France and begin adopting new U-boat tactics, did nothing to shake the belief that the U-boat had been mastered by a combination of asdic, Convoys, and airpower. Indeed, in a book on Modern Naval Strategy published by Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, RN, and F.E. McMurtrie (both respected naval theorists) in mid-940, submarine attack on an escorted convoy was given little chance of success. Supposing the submariner could find the convoy in the first place, his distorted view of the world through a periscope was considered a grave handicap. With a periscope exposed in broad daylight- the only time, the authors believed, that an attack was possible- the submarine invited swift retribution from both escort and merchant vessel alike.

Moreover, it was still generally believed that once a submarine was locked in asdic’s grip, destruction would follow from easily placed depth charges. This view of ASW would come to be utterly shattered by the Germans resourceful use of the U-boat in the second winter campaign on the sea lanes, and by events like the aforementioned three-hour hunt of the St. Laurent. asdic was nowhere near perfect, and neither was depth charge placement (inexperience of Canadian sailors may have also played a role, as did their older asdic sets). There were not enough escorts to protect the convoy against multiple attackers, and air power was not as readily available or capable as hoped. The Mid-atlantic air gap did not yet exist because not all the air bases that would be built by the end of the war were in place or even under construction yet, Canada’s pre-war air force was, as mentioned in Part 1, small, and though it was growing rapidly, it was not necessarily equipped or training for ASW. England herself had needed almost every available pilot during the Battle of Britain, and despite their victory many pilots had been killed. And Germany was only going to build more U-boats, now with a far greater flexibility to deploy them than they had ever had in World War One.

The only answer to the shortage of escorts was expansion and fundamental to the whole problem of expansion was the availability of ships, and here too the RCN’s plans in the early war were never reliable. To upgrade local defences, to replace decrepit auxiliary vessels, and to provide A/S ‘strike forces,’ the RCN had to undertake a serious shipbuilding program beyond that conceived in pre-war plans. To bolster local defences it was decided early on to build Bramble-class sloops and a small number of additional minesweepers. Further consideration was also given to the acquisition of Tribal-class destroyers. But the coming of war so early in the navy’s planned expansion threw it into serious disarray. Tribals could not be built in Canada without significant help from British firms, and with British industry now fully absorbed in its own war work little help could be expected. Unfortunately, the RCN rejected a very sensible British suggestion that it seek expertise in naval ship construction in the US. The Canadian navy also failed, initially, to obtain permission to place orders for Tribals in British yards. Faced with an almost impossible dilemma, the Naval Staff hit upon the idea of bartering less-sophisticated Canadian-built warships for British-built destroyers. The scheme had all the advantages of specialization. It permitted Canada to turn products from less-skilled manufacturers into high-value, long-term investments. For the government it meant good business and the possibility of future orders. For the RCN it meant the fulfilment of its expansion plans.

(HMCS Cartier, later HMCS Charny, in October 1940. An old Canadian Hydrographic survey vessel from 1910 pressed into service. Used for Naval Training and Naval Mine Avoidance Navigation.)

As the Naval Staff sorted through the problems of destroyer acquisition, it also tackled the question of what type of auxiliary warship to build for its own purposes and what type to build for bartering. Initial hopes of building sloops were dashed by the news that Canadian yards were incapable of building even small warships to naval standards. As the problem was being discussed, basic plans for a much simpler auxiliary ship arrived at Naval Service Headquarters from the National Research Council, which had acquired plans for ‘whale-catchers’ in July 1939 during a fact finding trip to the UK. The whale-catchers immediately appealed to the Naval Staff as a workable substitute for sloops, given that they were intended to be auxiliary vessels for inshore duty. Moreover, their mercantile construction was ideally suited to Canadian yards, and British adoption of this class made them suitable for bartering. Once agreed that corvettes (as the whale-catchers were called by early 1940) were to be built as the navy’s primary A/S ship and as the means whereby larger vessels might be acquired, the Naval Staff had to decide how many would be produced.

Meanwhile at sea, for a year or more, Saguenay and a handful of other River-class destroyers had conducted Canada’s naval war virtually alone. Since spring they had fought beside British warships against submarines prowling the coasts of Britain as part of the anti-invasion fleet. When the ships and RAF Coastal Command planes made things too difficult there, the U-boats moved west. With Iceland now usable as a base, the aircraft and escorts followed them. The Canadian destroyers escorted small outbound convoys to their dispersal point, roughly 12-15 degress west, and then shepherded an in-bound convoy through shallow waters to its UK destination. On December 1st 1940 whilst escorting a convoy, Saguenay was struck on her port bow by a torpedo fired by the Italian submarine Argo. The first Canadian naval vessel to take a torpedo hit. The ship was very nearly lost, with a bent propeller shaft, a major fire amidships, a section of the hull broke off and sank. The crew were able to keep the ship afloat and moving at a modest two knots. Five officers and thirty-five crew were evacuated to the RN destroyer Highlander to reduce casualties in case of another torpedo attack; and throughout the night and most of the next day a skeleton crew fought back the fires. Tugs arrived later that evening, but the ship had built up to a respectable six knots by that point and figured she could go on alone. At noon next day she was rounding the north of Ireland with all fires out and her steering gear back in operation. She struck a mine as she approached Barrow-in Furness, and with new stern damage and salt mixed in with her fuel, she had to accept a tow, and reached port on December 5th.

(HMCS Saguenay near Montreal, 1932)

Saguenay lost twenty-three men and sustained grievous injury to herself but she had done the job she was supposed to do: the speed with which her guns went into action, said an Admiralty report, had forced the U-boat under and prevented it from attacking any merchant ships. More and more Canada’s burgeoning sheepdog navy was being forced into a new way of thinking, moving away from pre-war training and ideas. Sink U-boats when able, above all protect the convoy. Now Saguenay would be out of action for several months. Six destroyers had grown to seven with Assiniboine in October 1939, then back to six with the loss of Fraser in June 1940. HMS Margaree had been purchased from the British to replace Fraser, but had been lost herself in a collision with a freighter on a squally Atlantic night in October 1940 with the loss of most of her crew.It was her first escort mission. Skeena was refitting in Halifax, leaving only five destroyers to bolster the British. Now, two months later Saguenay was out of action and the battle was only expanding.

It was a dark prospect, but coincidentally Saguenay’s removal happened around the same time that help finally began to arrive from two sources. One was from the arsenal of an “ally”, the other from Canada’s own shipyards. The ‘Four-Stackers,’ the 50 overage destroyers given by the United States in exchange for 99-year leases on British bases in the Western Hemisphere, began to arrive for transfer in December 1940. Mackenzie King had been involved in the deal from the beginning, often acting as an intermediary between Winston Churchill and Roosevelt. The Americans were also pressing for base rights in Canada itself and President Roosevelt wanted Canada to receive some of the destroyers being transferred. The Canadian government was not interested in granting base rights for what it felt was a small number of “ancient” destroyers, but the navy was told to prepare for them should they be forthcoming. The navy was less than enthusiastic. The ships were no suitable replacement for the River-class currently in service, and were of no long term value whatsoever.

Rear Admiral H.G. DeWolf, who was an acting captain and director of Operations in Halifax in late Summer 1940, recalls that the navy only grudgingly accepted the deal after Admiralty pleas for the RCN to take at least some of the ships. In the end Canada received seven of what became known as the Town-class (the RN designation), six of which were named for Canadian rivers, the seventh, Hamilton, saw some RN service before transfer to Canada. As the U.S. ships arrived in Canadian ports en route to England, the new crews were struck by American generosity; every inch of storage space was crammed with provisions now only a memory in England. There were bunks instead of hammocks; there were typewriters, radios, coffee-making machines. There were also defects which became apparent at sea. The lean, four funneled destroyers, emergency vessels laid down during the last year of the First World War, had been built in haste for a less technical conflict. They were not sufficiently maneuverable against U-boats and their sea-keeping qualities left much to be desired. narrow beam and shallow draft made them difficult to handle in rough weather. The messdeck bunks, for all their pleasant appearance, made exorbitant demands on the men’s crowded living space. Their steering gear was flimsy and cranky. Any ships were better than no ships however, and although seldom loved and frequently hated by those condemned to sail them, four were sent to bolster the destroyers already operating with the British. They would eventually form a crucial element of the fleet’s escort forces by virtue of their few positive qualities. They were fast and well armed. Commodore L.W. Murray went with them and took command of Canadian ships and establishments in the United Kingdom.

(Newly named HMCS Columbia, one of the ‘Four-Stackers’ given to the RCN by the United States as part of the Destroyers for Bases deal…)

The autumn and winter of 1940 also saw the first of Canada’s new “corvettes” waddle their way down the St. Lawrence river into RCN service.

Returning to the Autumn of 1939, for purely RCN purposes, the navy estimated that around 40 Anti-submarine vessels were needed over three years. Since some of the requisitioned ships were suitable for local duties, not all of the new vessels need be corvettes. It was also necessary to establish a rate of exchange if the smaller ships were to be bartered for Tribals. Quick resolution of these issues was essential if the full complement of the RCN’s first planned expansion phase (two Tribals, twenty corvettes, and twelve minesweepers) was to be in commission by Spring of 1940, as the Naval Staff hoped. The RCN did not get off the mark as quickly as it wished. Detailed drawings needed to begin construction of corvettes did not arrive from Britain until early 1940. The placing of orders was also complicated by the requirement that the navy deal with contractors through a third-party, the War Purchasing Board (later the Department of Munitions and Supply). In fact, the lack of official links to manufacturers and the interposition of another department between NSHQ and industry seriously complicated the process of modifying specifications in light of rapidly changing requirements. The first orders for corvettes to Canadian accounts therefore were not placed until February 1940, when contracts were let for fifty-four. Of these, only twenty-four, or perhaps thirty-four (roughly equivalent to first expansion phase) were intended for RCN service. The remainder were to be bartered for destroyers. Ten more corvettes were ordered by the RCN before the end of the month as replacements for war-weary ships and to maintain a steady rate of construction. By the end of February the issuance of contracts for what became known as the First Construction Program was completed: sixty-four corvettes and twenty four Bangor minesweepers ( for which it was not possible to find enough contractors until August 1940). Thus, when the barter scheme fell though in March 1940 because an exchange rate could not be agreed upon, the RCN found itself ‘holding contracts for considerably more corvettes than it intended to build.’ The contracts could have easily been cancelled, most had only just been signed. Fortunately, the RN agreed to take ten of the vessels built in Canadian yards, lowering the total for Canada down to 54, only seven more than what the navy had intended to have by 1942 anyway. For this reason, as well as political and economic ones, the orders were allowed to stand. Indeed, in August 1940 a further six corvettes were ordered along with ten more Bangors to maintain a steady rate of construction in the shipyards.

What this embarrassment of riches meant was an acceleration of the navy’s hitherto cautious expansion plans and the jamming of three years of careful growth into two. Personnel requirements quickly overtook projections, but NSHQ was not particularly troubled by the extra auxiliaries, particularly when the failure of the barter scheme was followed by the news that the British would allow Tribals to be built for the RCN in England. This ensured the desired main thrust of the expansion would go ahead and two would be ordered in early 1941 though none would be completed in time for the end of the first expansion phase. As an interim measure, the RCN requisitioned three small liners, Prince David, Prince Henry, and Prince Robert, and converted them to armed merchant cruisers (AMCs). They would remain Canada’s most powerful ships until the first Tribals arrived in 1943.

(HMCS Prince Robert in June of 1942. All three AMCs were converted to other purposes later in the war)

The matter of building Tribals in Canada was never wholly abandoned, as the navy was pleased to receive them from Britain but wanted more to fulfill its long term plans. Captain G.L. Stephens, Engineer-in-chief, advised against attempting such complicated building in Canada in the middle of a war. It was bound to be a long and expensive proposition, he warned, if for no other reason than that it was hardly worth tooling up industry to produce specialized steel plate and equipment for so small an order. moreover, Stephens believed, construction of Tribals was likely to tie up manpower and resources which could be better used. Nelles agreed with his engineer’s views but felt that if such ships could be built in Canada, the navy should not waste its time on smaller ‘stepping stones.’

The problem had also been considered by the government. Macdonald was under considerable pressure from politicians and the press in his home province to secure wartime capital investment in Atlantic Canada. Indeed, although Canada was prospering from the war, an incredibly small percentage of new capital investment found its way eastward. Of all the new contracts, only three had gone to Atlantic Canada and all to New Brunswick based Saint John Drydock and Shipbuilding. The prime minister wanted Halifax to get contracts for merchant ships, but Macdonald wanted Halifax to get contracts for destroyers. Macdonald sent a letter to C.D. Howe, Minister of Munitions and Supply, outlining how he felt the merchant ships would be useless without escorts to ferry them. Howe had barely survived the sinking of the SS Western Prince in December 1940, and was well aware of the need for escorts. Furthermore, Howe wanted some construction undertaken soon in order to stabilize the employment situation for ship-repair workers, and thereby establish a pool of skilled labour for use in an emergency. Owing largely to the need to retool industry, it was not until September 1942 that the first keel was laid, and in the rush to complete the hulls the Tribals drained manpower away from essential ship-repair tasks: quite the opposite of the original intention, and precisely the fear expressed by the navy’s senior engineer.

(Hull of R.C.N. corvette (probably H.M.C.S. “Moncton”) under construction at Saint John Drydock and Shipbuilding Ltd. 18 of August 1940)

Returning to Winter 1940, the Towns were being taken into service, the first corvettes arrived, and the navy’s River-class destroyers were returned to open ocean convoy escort duties. With the U-boats now operating from the Atlantic littoral and with the adoption of pack-tactics, losses to convoyed shipping had mounted during the second half of 1940. From the outbreak of war to February 1940, only seven of the one hundred and sixty-nine ships lost to enemy action had been sailing in convoys. In August, the U-boats began attacking at night and on the surface in the style of torpedo boats, losses jumped quickly. In September alone, forty of the fifty-nine U-boat attacks on shipping were directed at convoy targets. With the adoption of these tactics by the Germans the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’, as it captured the popular imagination and forms the basis of this study, finally began.The intensification of the U-boat campaign on Allied shipping eventually forced a reallocation of all ships to escort duty.