The Pittsburgh Press (April 18, 1945)

Famed war reporter killed by Jap bullet on Ie, off Okinawa

Ernie Pyle – He joins thousands of his beloved G.I. Joes.

WASHINGTON (UP) – Ernie Pyle, the greatest frontline reporter of this war, was killed in action this morning.

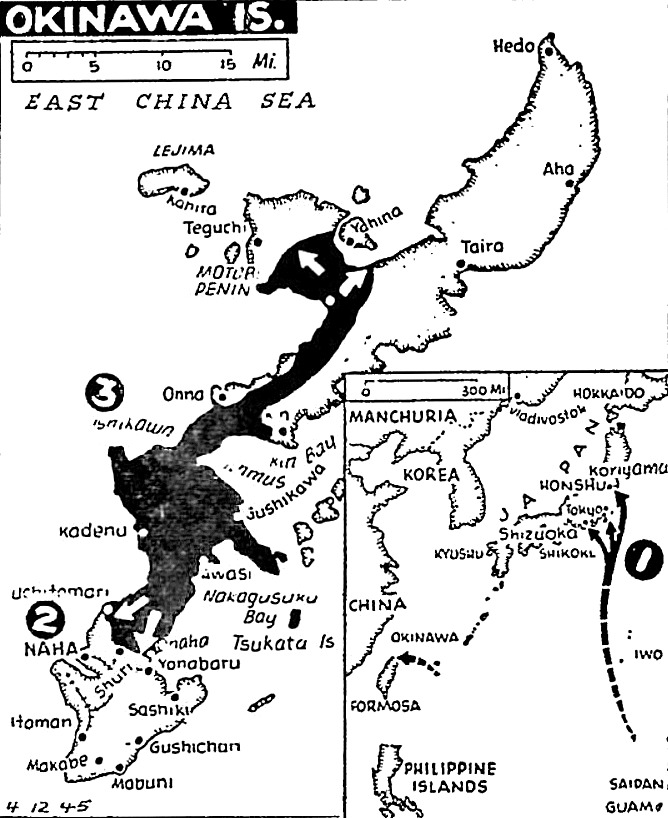

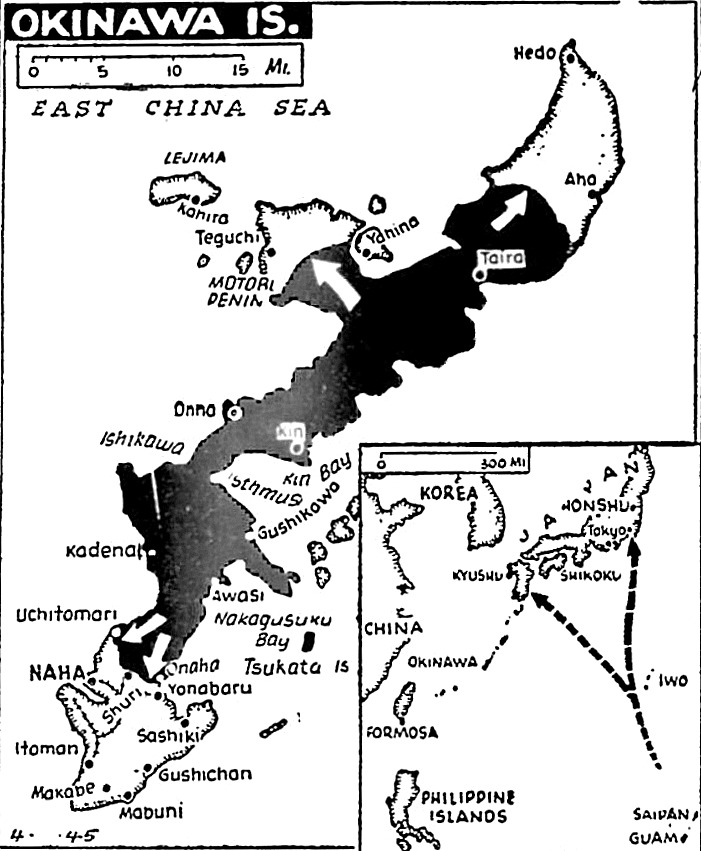

The skinny little Scripps-Howard and Pittsburgh Press war reporter – beloved of U.S. fighting men the world over – was killed by a Japanese machine gun bullet on the little island of Ie, off Okinawa.

He was killed, Secretary of the Navy Forrestal said, in the company of “the foot soldiers, the men for whom he had the greatest admiration.”

Vice Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner, commander of amphibious forces in the Pacific, reported from Guam that Mr. Pyle was killed outright about 10:15 a.m. Guam Time (Tuesday night ET) under Japanese machine gun fire on the outskirts of the town of Ie, on the island of Ie, four miles west of Okinawa.

Often close to death

He had come close to death countless times before – in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and France.

Mr. Pyle started covering the war in England and North Africa. He stayed with it, except for a brief furlough home, until the Americans were sweeping the Germans out of France.

Then he came home again, leaving the front, he explained, simply because he couldn’t stand the sight and smell of death any longer.

He didn’t want to go to war again, but he felt he owed it to America’s soldiers and sailors and Marines to report what they were doing in the Pacific.

He landed on Okinawa on what they called “Love Day” – the day of the first assault.

Truman expresses grief

The news of Mr. Pyle’s death saddened an already bereaved White House. A few moments after the report got out, President Truman said:

The nation is quickly saddened again by the death of Ernie Pyle. No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. More than any other man he became the spokesman of the ordinary American in arms doing so many extraordinary things. It was his genius that the mass and power of our military and naval forces never obscured the men who made them.

He wrote about a people in arms as people still, but a people moving in a determination which did not need pretensions as a part of power.

Nobody knows how many individuals in our forces and at home he helped with his writings. But all Americans understand now how wisely, how warmheartedly, how honestly he served his country and his profession. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen.

Mr. Pyle was a foxhole reporter. He said he knew nothing about strategy or tactics. What interested him was the G.I. in the dust and the muck. So that is what he wrote about.

He had spent the years before the war writing a rambling column about places he had seen and people he had met.

He lacked the physique for war. He was slight, weatherbeaten, gray-haired, and balding. He was ill much of the time. He was no longer young – he would have been 45 on August 3.

But he liked people. When he went to war, he kept on writing about people. The people he wrote about were in fox-holes, so Emie spent a lot of time in foxholes.

Secretary Forrestal said in a statement that Mr. Pyle “was killed instantly by Japanese machine gun fire while standing beside the regimental commanding office of Headquarters Troops, 77th Division, U.S. Army.”

Mr. Forrestal added:

Mr. Pyle will live in the hearts of all servicemen who revered him as a comrade and spokesman. More than anyone else, he helped America to understand the heroism and sacrifices of her fighting men. For that achievement, the nation owes him its unending gratitude.

Secretary of War Stimson was shocked into momentary silence by the news. Then he said:

I feel great distress. He has been one of our outstanding correspondents. This is the first I have heard of his death. I’m so sorry.

Speaker Sam Rayburn voiced the sentiment of his congressional colleagues: “I think he was one of the great correspondents of all time.”

Once in North Africa, some German Stukas began dive-bombing and strafing the place where Ernie was. He dived into a ditch behind a soldier.

When the raid was over, he nudged the soldier and said, “Whew, that was close, eh?” The soldier didn’t answer. He was dead.

Mr. Pyle, saying over and over again that he was constantly afraid, went from near-miss to near-miss, from North Africa to Ie.

Once at Anzio a bomb knocked him out of his bunk. He reported it, but most of the column for that day was about the others who were in the hut with him. He told how Robert Vermillion, United Press reporter, tried to get out from under the debris and couldn’t. Said Vermillion, “Hey, somebody get me out of here.”

In France, Mr. Pyle finally saw all the death he could stand for a while. He wrote candidly that he could no longer take it. He had to come home.

Soldiers wrote him letters telling him they knew just how he felt, and they didn’t blame him.

But Mr. Pyle couldn’t stay away from a war that he felt was his as much as it was the Joes fighting it. So, he went to Okinawa.

In the Pacific he went aboard an aircraft carrier n Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s task force. He covered two naval air attacks on Tokyo in February and the invasion of Iwo Jima.

But he couldn’t stay away from the foot soldier, so he asked to be assigned to the Marines for the Okinawa campaign.

Before he departed, he had his belongings packed. He left instructions for their shipment if anything happened to him.

Went in with Marines

He went ashore at Okinawa with the 1st Marine Division. Then he went with an Army division to invade Ie last Monday. He watched the Doughboys move quickly ashore and capture the island’s three-strip airfield and gain control of the western two-thirds of the island.

It was as the troops pushed eastward to root out Japs dug in on the Iefusugu Mountain north of the town of Ie that Mr. Pyle was killed.

Everywhere he went, Mr. Pyle found fighting men looking for him. They told him their stories, and he always got their names and addresses right.

If he slept on the ground with a bunch of exhausted soldiers, he wrote a column about them in the morning. If the bombs came close, he told how the men took it.

Told everything

If they were hungry and dirty and homesick and grumpy and sick of war, he told about that, too.

Ernie’s columns about combat troops won them an increase in pay. He didn’t pretend to be a molder of opinion, he just thought that if airmen and others got extra pay for combat duty, the men with the rifles ought to get it, too. He said it would be good for their morale Congress agreed.

Mr. Pyle didn’t know any long words. At any rate, he never used them. He could write with great feeling and sharp discernment, with poetic feeling, even.

Loved by all

What he wrote hit a day laborer as hard as it hit a college professor.

The ordinary people loved him; witness the stream of letters-to-the-editor which flowed constantly into the newspapers which carried his column.

The learned also loved him, and showed him their respect. Witness the honorary degree bestowed upon him by his alma mater, Indiana University. They called the degree “Doctor of Humane Letters.”

Born in 1900 on farm

Ernie Pyle was born August 3. 1900, on a farm near Dana, Indiana. His father, William C. Pyle, still lives there. His mother, about whom he wrote from time to time in his column, died while he was in England in March 1941.

His full name is Ernest Taylor Pyle. Taylor was his mother’s maiden name.

He was married July 7, 1925, to Geraldine Siebolds, then a Civil Service Commission government clerk in Washington. She came from Stillwater, Minnesota. Mrs. Pyle lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they built a home a few years ago.

Went to Indiana U

Ernie attended Indiana University for three and a half years and quit without graduating. He broke into the newspaper business on the La Porte (Indiana) Herald, then was moved to Washington, D.C., by the late Earl Martin, then editor of Scripps-Howard’s Washington Daily News.

He worked on The News from 1923 to 1926, when he was overcome by a yen for travel. He and “Jerry” drew out their savings, bought a Ford Model-T roadster, and the two of them drove clear around the rim of the United States in a leisurely way.

The trip wound up in New York, and Ernie worked as a desk man on The Evening World and The Evening Post for a year or two, until he was talked into returning to The Washington News as telegraph editor. There he worked up a terrific interest in aviation and started doing an aviation column on the side. It was a success and Ernie had an enormous acquaintance among airmen who are veterans of those days.

How column was born

He was made aviation editor of the Scripps-Howard Newspapers. Then in 1932 he was appointed managing editor of The Washington News.

Early in 1935, the Pyles took a vacation in Arizona. When they got back, the late Heywood Broun happened to be taking a vacation too, so Ernie wrote a dozen columns about his own vacation experiences to fill the Broun spot in The News. They made good reading and the eventual result was a decision by G. B. Parker, editor-in-chief of the Scripps-Howard Newspapers.

He and Jerry set out

So, Ernie and Jerry set out, by auto. The first of his columns appeared August 8, 1935, under a Flemington, New Jersey, dateline. He has been writing a piece a day ever since, except for an occasional timeout for rest.

Those early columns were leisurely copy, concerned with scenes and people and incidents encountered as he and Jerry drove around the country. He didn’t write “news.”

The Washington News ran the pieces regularly from the start, and has never missed one. Other Scripps-Howard papers gradually began using them, and eventually all were printing them as a fixed daily feature. The United Feature Syndicate began syndicating the column to non-Scripps-Howard papers.

Combed the continent

In those first few years Ernie, usually with Jerry traveling beside him, combed the United States, Canada, Mexico, Alaska, the Hawaiian Islands, Central and South America. He traveled by train, by plane, by boat, on horseback, muleback and by truck, but most of the time he drove a convertible coupe.

He spent several days at the leper colony on Molokai Island, went up the Yukon on a boat. flew to the Bering shore of Alaska, went down in mines and up on dams, drove from Texas to Mexico City before the famous highway was finished. He interviewed the great and the little.

His daily column contained human interest – whether whimsy or pathos, incident or personality. He eventually worked into it so much of his own personality that readers began to regard this stranger as an old friend.

Was in blitz

In 1940, Ernie went to England, and the blitz. Shortly after his arrival in London he went through the great firebombing during the holiday week of December 1940, and cabled home an account of “the most hateful, most beautiful single scene” he had ever witnessed.

Portions of the dispatch were cabled back to London and reprinted in London papers.

He spent some months in England and Scotland, and his dispatches from there were reprinted in book form.

Then he came back to the states for a rest. He was at Edmonton, Canada, preparing to shove off by plane over the new air route to Alaska, when word reached him that his wife was dangerously ill in Albuquerque. He flew to Albuquerque, and stayed with her for months until she recovered.

Just missed Pearl Harbor

Later he made all arrangements for a trip that would have taken him to Honolulu, Manila, Hong Kong and Australia. His clipper booking was cancelled to make room for propellers for the Chinese.

While he cooled his heels, this clipper arrived over the Hawaiian Islands during the Jap attack on Pearl Harbor.

In the early summer of 1942, he went to the British Isles, where he spent several months with our troops training in Northern Ireland and England.

Then came the invasion of Africa. He did not go in with the first wave, but arrived shortly thereafter.

Ernie spent much of his time living in the field with the troops. During the fighting in Tunisia, he went four and five weeks at a time without a bath, sleeping on the ground and on farmhouse floors, under jeeps and in foxholes.

Friends also killed

Many friends of Ernie’s have been killed in this war, including, aside from soldiers, Raymond Clapper of Scripps-Howard, Ben Robertson of The Harold-Tribune and Barney Darnton of The New York Times.

Ernie once wrote a friend:

I try not to take any foolish chances, but there’s just no way to play it completely safe and still do your job. The front does get into your blood, and you miss it and want to be back. Life up there is very simple, very uncomplicated, devoid of all the jealousy and meanness that float around a headquarters city, and time passes so fast it’s unbelievable. I didn’t have my clothes off for nearly a month, never slept in a bed for more than a month. It was so cold that my mind would hardly work and my fingers would actually get so stiff I couldn’t hit the keys.

Few of his readers knew it, but Mr. Pyle got a brief look at service life in the last war, although he never went overseas.

He enlisted in the Naval Reserve at Peoria, Illinois, on October 1, 1918. He was 18. He was released from active duty after the armistice but remained in the reserve and took a two weeks training cruise aboard the training ship Wilmette. He was honorably discharged on September 30, 1921, when the Navy cut down its reserve force for reasons of economy.

Mr. Pyle’s African dispatches were also published in book form.

In Sicilian invasion

Ernie was in on the invasion of Sicily, and soon after that came back to the states for a two-month rest. Then. he returned to the Mediterranean Theater, spent some months with the Fifth Army in Italy, and then went to England to await the invasion. He went into Normandy on D-Day plus one.

His column appeared in more than 300 newspapers, including the Army newspaper Stars and Stripes.

Ernie stayed in France through the battle of the breakout. He was almost killed by U.S. bombers at the time Lt. Gen. Leslie McNair was killed.

After the liberation of Paris, he decided he had “had it,” and came home for a rest in Albuquerque and a visit to Hollywood, where a film based on his experiences has just been completed.

He left early this year for the Pacific.

Gained wide honors

In 1944, Mr. Pyle was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for distinguished correspondence in 1943. He was voted the outstanding Hoosier of the year by the Sons of Indiana of New York. In October 1944, the University of New Mexico conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters.

In November 1944, the University of Indiana conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters.

Sigma Delta Chi awarded him their Raymond Clapper Memorial Award for war correspondence in 1944. In both 1943 and 1944, he received a Headliner’s Club award.

Mr. Pyle’s third book, Brave Men, was the December 1944 selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club.

Dreaded going back

Lincoln Barnett, in an article in Life Magazine last month, said the G.I.s’ own war correspondent didn’t want to go back to the war – any more than any other man who braves death in the battleline.

“I dread going back and I’d give anything if I didn’t have to go,” Mr. Pyle told the author after his return from Europe. “But I feel I have no choice I’ve been with it so long I feel a responsibility.”

Ernie Pyle’s five-foot, eight-inch frame carried only 112 pounds. Despite his appearance of fragility, the sparse-haired little man lived with the fighting men, lived as they lived – and he died as they die.

Mr. Barnett wrote that:

Ernie has come to be envisaged as a frail old poet a kind of St. Francis of Assisi, wandering sadly among the foxholes, playing beautiful tunes on his typewriter. Actually, he is neither elderly, little, saintly or sad.

Extracts from article

Extracts from Mr. Barnett’s article follow:

Success thrust itself upon him… he cares nothing for the money it has brought, and is embarrassed by the fame… but he keeps going because he feels that he must.

Although Pyle is America’s No. 1 professional wanderer, he is fundamentally a sedentary person who likes nothing better than to sit in an overheated room with a few good friends. Sometimes he appears to find conversation less pleasurable than the simple circumstance of being seated.

His apparent agoraphobia is a byproduct neither of war nerves nor a swelled head. He has always been self-effacing, and he finds himself uncomfortable in his current eminence as the nation’s favorite war reporter, Pulitzer Prize winner and author of two bestsellers.

Not timid

He has been called shy, but he is not timid. His reticence is marked by quiet dignity.

He likes people as individuals and writes only nice things about those he mentions by name in his column, “But there are a lot of heels in the world,” he says, “I can’t like them.”

The Life article points out that Ernie has always been an apostle of the underdog. Seven years ago, after visiting a leper colony, he wrote that “I experienced an acute feeling of spiritual need to be no better off than the leper.”

“And so in war,” says Mr. Barnett, “Pyle has felt a spiritual need to be no better off than the coldest, wettest, unhappiest of all soldiers.”

The article relates that when Ernie gave his consent to the making of the movie, The Story of G.I. Joe, he stipulated that (1) the hero of the picture must be the Infantry and not Pyle; (2) that no attempt be made to glorify him, and (3) that other correspondents be included in the story.

The movie, in which Capt. Burgess Meredith plays Ernie, will be seen by troops overseas in June and be released to the civilian public in July.

Huge earnings

In spite of his refusal to capitalize on his fame when he returned from the European fronts, Ernie has made close to half of a million dollars in the past two years, Mr. Barnett estimates.

While he was home, he wore one suit, which he bought for $41.16 when he landed in New York. His home is a modest house in Albuquerque, which cost about $5,000. He puts his money into war bonds and, according to Mr. Barnett, quietly bestows substantial sums upon “friends, relatives, G.I.’s and anybody else he likes.”

Hundreds pray for him

The article continues:

Although Pyle disdains his affluence, he is keenly appreciative of the aureole of national esteem and affection that now envelopes him.

The emotions Pyle evokes in his public go beyond detached admiration. He is probably the only newspaper columnist for whom any notable proportion of readers have fervently prayed.

For some time after D-Day, 90 percent of all reader queries that came into Scripps-Howard offices were: Did Ernie get in safe?

His success has been achieved without much push on Emie’s part, the article maintains.

It declares that he took journalism at the University of Indiana because someone told him it would be an easy course.

Two years after going to Washington, Ernie married Geraldine Siebolds, an attractive girl from Minnesota who had a job with the Civil Service Commission. Later, when he became a roving reporter, she was known to millions as “that girl.”

He goes to war

“A small voice came in the night and said Go,” Ernie wrote in the fall of 1940. It was the same voice that had spoken to him in the leper colony in Hawaii. So, he went off to war.

Pyle’s first overseas trip in the winter of 1940-41 multiplied readers of his column by 50 percent. Stirred by the spiritual holocaust of London and his own relentless instinct for self-immolation, he produced columns of great beauty and power. But it was not until he reached North Africa the following year that the Pyle legend began to evolve.

The article tells how Ernie, afflicted by one of his periodic colds, remained in Oran while the other reporters went to the front. There he met some obscure civilians who told him about the turbulent political situation in North Africa and he scored an important scoop.

The Doughboys’ saint

Gradually, as he moved about among the soldiers, covering the “backwash” of the war, he became the patron saint of the fighting foot soldier, the article relates. But he didn’t know it for a long time.

He thought, when he wrote it, that his famous column on the death of Capt. Waskow was no good.