On the morning of 27 May 1942, Lieutenant D. F. Parry overheard an exchange between a British ‘forward’ officer from 3rd Indian Brigade at the southernmost tip of the Gazala Line held by 8th Army covering Tobruk and Egytian Libyan border and a colleague embedded at XXX Corps headquarters at El Adem. Had it not been reported verbatim, the conversation might be presumed to have formed part of a Monty Python sketch forty years later.

OFFICER : There is a cloud of dust to the south; it has the appearance of a military formation.

REPLY FROM XXX CORPS : There are no, repeat no, troops to your south …

OFFICER : The cloud of dust is growing larger. It is undoubtedly a military formation.

REPLY ( slightly irritable ): We repeat, there are no, repeat no, troops to your south.

OFFICER : Through the haze I can now identify tanks, difficult to identify but possibly German Mark IVs.

REPLY ( irritably ): We repeat, there are no troops, repeat no troops, to your south.

OFFICER : I am counting Mark IVs – one, two, three, four, five, six, seven – there is no doubt, repeat no doubt, that this is a large German force. Mark IVs number over thirty, and there are also Mark IIIs and a large number of motorized infantry. This could be, I repeat, this could be the Afrikakorps moving at a speed of approximately 30 miles per hour towards El Adem.

REPLY ( with air of resignation ): There are no forces in your area.

OFFICER : I have been spotted by the enemy and am under fire. I repeat, it is a large enemy formation and probably the Afrikakorps moving fast northwards.

REPLY ( very bored ): There are no enemy forces in your area.

OFFICER : It is undoubtedly the Afrikakorps moving at speed towards El Adem. I am under … In the background it was possible to hear the sound of exploding shells …

Then there was silence. Rommel’s blitzkrieg – Operation Venezia – had been unleashed.

‘It will be hard, but I have full confidence my army will win it,’ Rommel had written to his wife the previous evening, ‘After all, they know what battle means. There is no need to tell you how I will go into it. I intend to demand of myself the same as I expect from each of my officers and men.’ Under cover of darkness he then took his place with the Afrikakorps, in a column, which along with the 90th Light Division and the XX Italian Corps, numbered 10,000 vehicles. ‘I was tense and keyed-up, impatiently waiting the coming day. What would the enemy do? What had he already done? These questions pounded my brain.’

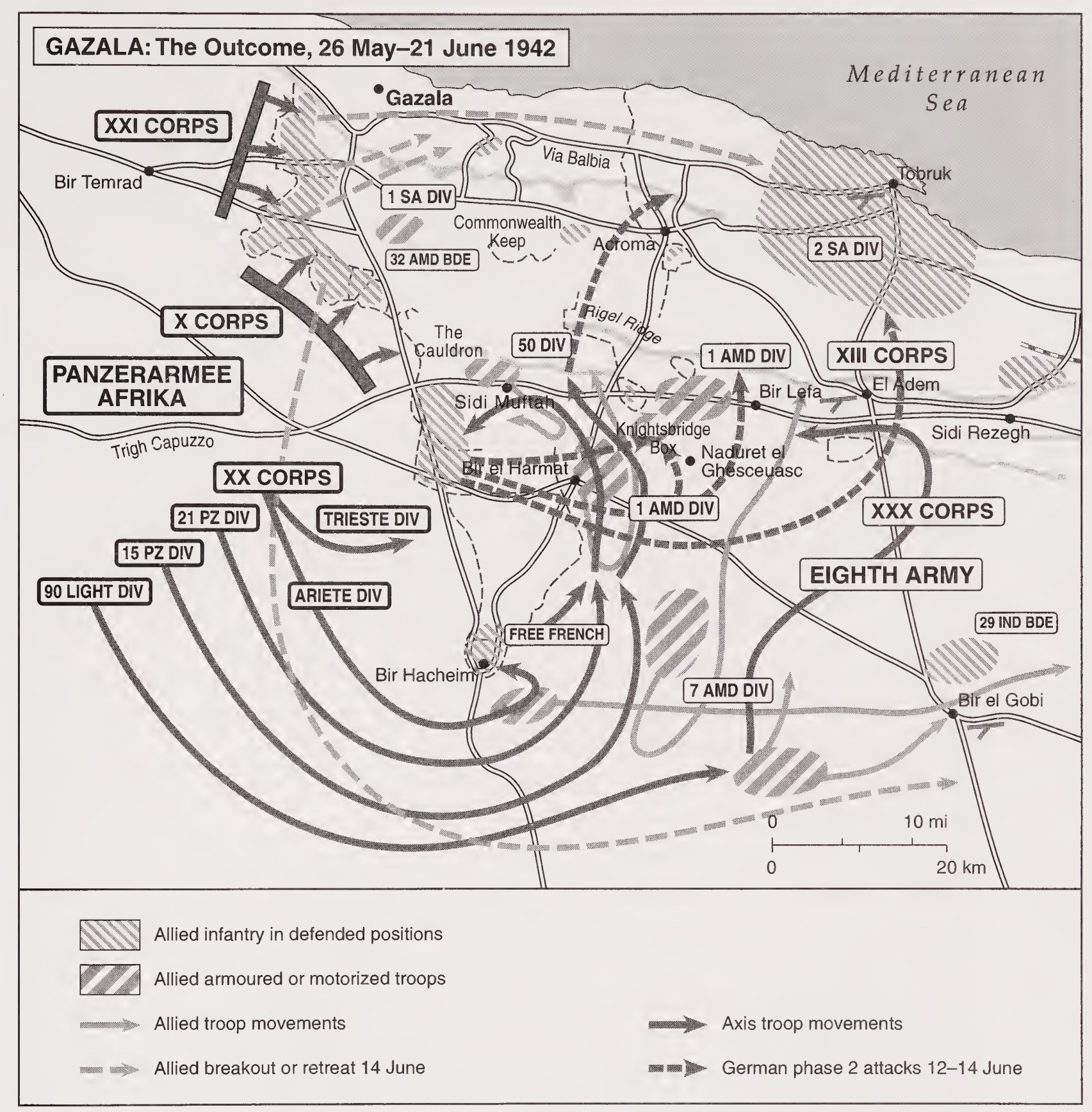

Six days earlier, General Claude Auchinleck commander of British Mediterranean and Middle East Theater , who was in Cairo, had sent a long letter to General Neil Ritchie commander of Eighth Army at Army headquarters. Clearly concerned about Ritchie’s well-attested limitations but anxious not to undermine his confidence (in this stage both Auchinleck and Ritchie were becoming strong candidates for worst Allied generals of war after Maurice Gamelin , Semyon Buıdyeni and Arthur Percival ) , Auk who had noidea how matters work in frontline thousands of miles away from Cairo wrote, ‘Do not think I am trying to dictate to you in any way, but this coming struggle is going to be so vital that I feel you must have the benefit of our combined consideration here.’ He identified two possible lines of attack that Rommel might open up. The first would be ‘to envelop our southern flank, seizing or masking Bir Hacheim en route, and then driving on Tobruk’; the second would be ‘a heavy attack on a narrow front … with the object of driving straight to Tobruk’. This, he warned, might be accompanied ‘by a feint against Bir Hacheim … with the aim of drawing off the main body of your armour to the south and so leaving the way open for the main thrust’. While he was careful to remind Ritchie that he should be prepared to face either option, he judged that ‘the second course is the one he [Rommel] will adopt, and is certainly the most dangerous to us’.

Unfortunately, Auchinleck had got it complately wrong. Rommel’s plan of attack was precisely the opposite of what the British commander-in-chief supposed. His feint was to the north, not the south. And Auckinleck having benefit of ULTRA intelligence about timing and general concentration of Panzer Army making that kind of blunder and not checking his errenous assumptions with air reconnicance (RAF grounded all of its recon flights before Axis offensive and neither British theater command nor Eighth Army command did not ask any recon flights ! till 26th May ) then misdirecting his less experienced and much more indecisive subordinate General Neil Ritchie (whom he kept in that position despite objections and votes of no confidence from his subordinates because Auckinleck assumed he could “hold his hand” and manage him and besides relieving his own staff officer Ritchie who had been loyal to him would look bad as a loss of face and demoralising) by interfaring his operations and planning , are a string of blunders made by a theater command rare in history of warfare. (In Red Army any theater commander made same mistakes and gaffes Auckinleck and Ritchie made , were relieved of command and executed immediately)

General Claude Auchinleck Commander in Chief of British Mediterranean and Middle East , strangely due to displaying a better image of British Army , his blunders and bad decisions in desert campaign were hushed by historians instead he was credited with halting Rommel’s already exhausted and out of breath and supply Panzer Army before Alamein Line which was impossible to outflank and under complate RAF air cover but none acknowledges or emphasizes his responsibility and misjudgements in defeat at Battle of Gazala , Fall of Tobruk and Mersa Matruh with 51.000 British and Commanwealth troops and vast amounts of supplies captured by a numerically inferior but way better led Panzer Army Africa that advanced all the way to Alamein before that. After First Battle of Alamein he was relieved of command finally and sent to India (where his heart was as an officer of Indian Army) as Indian Theater Commander in Chief. He should never been appointed to North Africa or Middle East in first place

General Neil Ritchie , both young and inexperienced , could not impose his authority on his subordinates , he should never been appointed to lead a multi national Eighth Army command which happened due to misjudgement of Auchinleck who assumed he could direct operations all the way from Cairo via Ritchie. Later Ritchie became an able if not outstanding corps commander in North West Europe Campaign.

Five hours before Rommel’s force headed for Bir Hacheim, his second-in-command, General Cruewell, launched a frontal attack with a German brigade and two Italian divisions for diversion to the north. But this was not ‘the main thrust’ towards the Gazala Line which Auchinleck had anticipated. His entire strength consisted of two small armoured units accompanied by camouflaged trucks, each mounted with whirring aero-engines that kicked up great clouds of dust which wafted across the desert to provide a convincing impression that a major onslaught was underway. Meanwhile Rommel’s ‘right hook’ advanced without impediment. Guided by dim lights concealed in used fuel cans planted in the sand, Rommel’s column swept south along a meticulously prepared route until, a little before dawn, they reached a location some twelve miles to the south-east of Bir Hacheim, the southern most fortress along the Gazala Line.

Destiny in Desert , The Road to El Alamein - Jonathan Dimbleby , BBC