“Hitler’s U-Boat War” , Clay Blair Jr.

“The War For All Seas” , Ewan Mawdsley

“World War II At Sea” , Craig L. Symonds

“The War With Hitler’s Navy” , Adrian Stewart

“Bismark” , William Shrier

“Pursuit” , Ludovic Kennedy

en. wikipedia

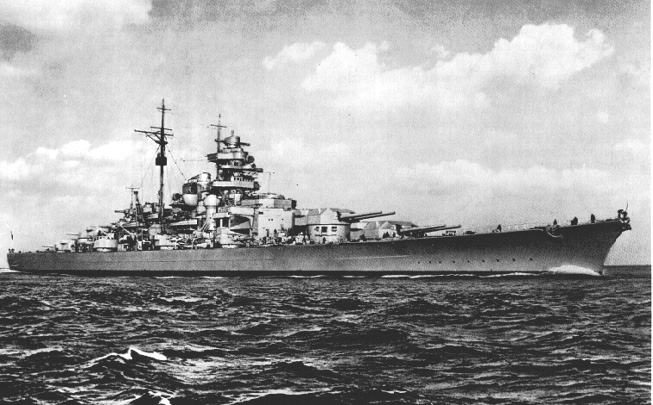

U-boat operations in the North Atlantic were interrupted on May 22 by the most dramatic event in the naval war to that time: the Atlantic sortie of the super battleship Bismarck. Admiral Raeder Commander in Chief of German Navy in Berlin despite objections of his staff , was planning a big operation with almost all capital ships of German Navy for a big merchant raiding maneuvere against British convoys in Atlantic , especially using newly constructed battleship , 42.000 ton Bismarck on her first battle sortie. Using almost all capital ships of Grman Navy was risky but Raeder with incoming Operation Barbarossa wanted to increase prestige of Navy i eyes of Hitler. The whole operation called Rheinubung and it involved both battlecruisers Scharnhost and Gneisenau in Brest (which made another commerce raiding in Atlantic in first months of 1941) , sailing from Brest and battleship Bismarck and Hipper class cruiser Prinz Eugen to break into Atlantic from Skajerak Strait and passing through North Sea and meanwhile by a miracle not to be detected by Royal Navy Home Fleet in Scotland.

Battleship Bismarck

Operation Rheinubung was fatally compromised before starting though. In Brest RAF Coastal Command determined to take out of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau with constant air raids , finally put a torpedo on Gneisenau on 6th April 1941 , severely damaging her. Scharnhorst also came up with machinery problems. As a result neither battleship could leave Brest yet and weight of whole operation fell on Bismarck and Prinz Eugen.

Accompanied by the new heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, Bismarck sailed from Kiel in the early hours of May 19. Bletchley Park could not read naval Enigma on a current basis in May; thus the British Admiralty had no advance warning from that source. But the British naval attaché in Stockholm learned of the sortie on the night of May 20 and alerted the Admiralty. The next day, RAF reconnaissance planes spotted the two ships near Bergen. Bletchley Park broke an old (April) Enigma message which stated that Bismarck had taken on board “five prize crews” and “appropriate charts,” which led the Admiralty to believe, correctly, that Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were embarked on a convoy-raiding sortie in the North Atlantic. When he got the news, Winston Churchill gave a simple—but legendary—order: “Sink the Bismarck!” All available capital ships of the Home Fleet and Force H from Gibraltar put to sea.

Bismarck and Prinz Eugen, equipped with primitive radar, entered fogshrouded Denmark Strait on May 23, hugging the ice pack off Greenland. Two 10,000-ton heavy cruisers, HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk, also equipped with primitive radar, were patrolling the passage. HMS Suffolk, which had better radar than Bismarck, found the Germans late that evening and brought up HMS Norfolk. Bismarck detected HMS Norfolk on radar and fired her first salvos of the war. She got no hits; moreover, the shock of her 15″ guns damaged her radar. As a consequence, Prinz Eugen moved into the van. Tracking by radar, HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk hung on tenaciously.

In response to the alert, the new commander of Royal Navy Home Fleet, Admiral John Tovey, sent the big (42,000-ton) battle cruiser HMS Hood and the new battleship HMS Prince of Wales, with destroyer screens, to intercept the German ships in the south end of the Denmark Strait. The four converging British ships significantly outgunned the German ships. HMS Hood, like Bismarck, had eight 15″ guns; HMS Prince of Wales had ten 14″ guns. HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk, like Prinz Eugen, each had eight 8″ guns. But HMS Hood was ancient (complated in 1918) and thinly armored, and newly built first King George V class battleship HMS Prince of Wales was still in workup and some of her guns were not yet firing properly. HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk, also ancient, were less well-armored than Prinz Eugen.

In the early morning hours of May 24, the opposing naval forces met. Admiral Holland commanding HMS Hood and HMS Prince of Wales made the mistake of opening the attack on a slanting course, which prevented them from bringing all guns to bear simultaneously, and which offered the Germans a better target. Mistaking Prinz Eugen for Bismarck, Hood opened fire on the former at a range of fourteen miles. Bismarck and Prinz Eugen responded immediately with deadly accurate fire. Taking a hit in her magazines, Hood blew up and sank within minutes. The British destroyer HMS Electra could find only three of her 1,419-man crew. Badly damaged by two hits and bedeviled with malfunctioning guns, HMS Prince of Wales disengaged and retired behind a smoke screen. But she had got two or three 14″ hits in Bismarck’s forward fuel tanks and a fuel-transfer station, which deprived Bismarck of a crucial thousand tons of fuel oil.

In view of the damage to Bismarck, the German commander, Admiral Günther Lütjens, changed plans. The Prinz Eugen was to separate from Bismarck and raid British shipping alone. Prinz Eugen’s engines malfunctioned at this moment so she couldn’t keep pace with Bismark anyway. (Prinz Eugen abandoned Operation Rheinenburg and reached Brest on 1st June 1941 without sinking a single ship) Bismarck was to go directly to St. Nazaire for repairs. Before the new plan could be executed, however, Lütjens had first to shake his shadowers, HMS Suffolk, HMS Norfolk, and the damaged HMS Prince of Wales, and the destroyers. He swung Bismarck at the shadowers—as if to attack—and during the resulting confusion, Prinz Eugen slipped away, southbound into the vast Atlantic.

When Dönitz learned that Bismarck had been hit, he volunteered the entire Atlantic U-boat arm to assist. Lütjens hastened to accept the offer and, as a first step, he requested that Dönitz set a submarine trap in grid square AJ-68, 360 miles due south of Greenland. The plan was that Lütjens would “lure” his shadowers into the square on the morning of May 25 so that the U-boats could attack them, causing sufficient diversion for Bismarck to elude them.

On the afternoon of May 24, Dönitz directed five boats to form the trap. Three of the boats were commanded by Ritterkreuz holders: Lüth in the old Type IX U-43, Endrass in the old Type VIIB U-46, and Kuppisch in the Type VIIC U-94, who had only a few torpedoes. The other two boats, fresh from Germany on maiden patrols, had not fired any torpedoes: the first Type IXC† to reach the Atlantic, U-66, commanded by Richard Zapp, age thirty-seven, and the VIIC U-557, commanded by Ottokar Paulshen, age twenty-five. Kleinschmidt’s IXB U-111 was to join the trap after refueling from one of Bismarck’s supply ships, Belchen. Two other boats, Helmut Rosenbaum’s U-73, fresh from Lorient, and Claus Korth’s U-93, took stations slightly to the east of the trap.

Dönitz set a second submarine trap in the Bay of Biscay, 420 miles due west of Lorient. It was comprised initially of four Type VII boats. Two of these U-Boats were out of torpedoes though. (U-98 , U-556) a total of fifteen boats, seven in western waters, eight in the Bay of Biscay were diverted from their patrol zones in Atlantic , and severely deplating German Navy combat power against merchant convoys (which would compound eventual fiasco and failure of Operation Rheinubung)

Late that evening, May 24, Bismarck’s shadowers drew the new aircraft carrier HMS Victorious onto her track. When HMS Victorious had closed to within 120 miles of Bismarck, she launched nine old Swordfish biplanes, each armed with a single 18″ aerial torpedo and fitted with primitive ASV radar. The Swordfish picked up a contact and prepared to attack, but the “blip” turned out to be cruiser HMS Norfolk, which by radio put the planes back on the correct course. A second “blip” proved to be three U.S. Coast Guard cutters, Modoc, Northland, and General Greene, on “neutrality patrol.” Immediately afterward, however, the planes found Bismarck. Courageously flying into a wall of antiaircraft fire, the Swordfish attacked within view of the Coast Guard cutters, scoring one hit. Astonishingly, all nine Swordfish survived and returned to HMS Victorious.

The single torpedo hit on Bismarck did no damage, but the attack had important consequences. During Bismarck’s violent maneuvering to avoid the torpedoes, the makeshift repairs to the damage sustained earlier in the day from HMS Prince of Wales fell apart and Bismarck lost more oil and took on tons of water, which slowed her. This mishap led Lütjens to abandon the plan to “lure” his pursuers into a submarine trap, and he headed directly for Brest, which was closer than St. Nazaire. Accordingly, Admiral Dönitz shifted seven of the eight boats (leaving U-111 to refuel) in western waters east toward the presumed track of Bismarck and moved the five boats in the Bay of Biscay trap farther to the north.

During the early hours of May 25, Bismarck shook her pursuers. The Germans rejoiced. If Lütjens could remain undetected and maintain speed, Bismarck would soon reach the Bay of Biscay U-boat patrol line and would be within range of Luftwaffe aircraft based in France, which could provide an aerial umbrella. The onset of nasty Atlantic storms would help Bismarck remain undetected. The British wept. The great prize had unaccountably slipped from their grasp. The stormy weather diminished hope that she could be found again.

Unaware of the severity of the damage to Bismarck and of her critical loss of fuel, the British did not know where she was going. South in the Atlantic? North back to Germany? East to France? Based on incorrect or botched plotting of DF fixes on Bismarck’s radio transmissions, Admiral Tovey leaned to the view that Bismarck was to break back to Germany via the Iceland-Faeroes passage, and wrongly deployed Home Fleet forces accordingly. At the same time, however, First Sea Lord Dudley Pound at the Admiralty directed Force H (the carrier HMS Ark Royal and the battle cruiser HMS Renown), coming up from Gibraltar, to deploy on the assumption that Bismarck was headed for France. Thus two of the three possibilities were covered, albeit thinly. But the nasty weather worked in Bismarck’s favor, restricting and blinding carrier- and land-based air patrols. During the desperate but fruitless hunt for Bismarck on May 25, the codebreakers at Bletchley Park, who were reading the Luftwaffe Red Enigma currently, but not naval Enigma, picked up an important message in Red that related to Bismarck. In response to a query from the chief of staff of the Luftwaffe, who was in Athens for the German airborne assault on the island of Crete, Berlin informed him that Bismarck was “making for the west coast of France.” Bletchley Park rushed this vital information to the Admiralty, but by that time both the British Admiralty and Admiral Tovey commander of Royal Navy Home Fleet had intuitively concluded that Bismarck was headed for France and were redeploying all naval forces accordingly. Nonetheless, the information from Bletchley Park was reassuring.

In the foulest possible weather, on the morning of May 26, the First Sea Lord Dudley Pound directed RAF Coastal Command and carrier-based air to concentrate reconnaissance along a presumed track to Brest. At 10:30—thirty-one hours after Bismarck had been lost—a newly arrived, American-built RAF Coastal Command Catalina piloted by RAF Flying officer F.A. Briggs found her. Ironically, its co pilot was a U.S. Navy ensign, Leonard (“Tuck”) Smith, who was “on loan” to indoctrinate RAF pilots to the peculiar flying characteristics of the Catalina. The British pilot, Briggs, got off a contact report in a simple code, which B-dienst quickly broke and transmitted to Bismarck and to Dönitz.

Bismarck was then 690 miles west of Brest—about thirty-five hours out—but Force H was only seventy-five miles to the east, blocking her way. The Force H commander, Admiral James F. Somerville (who bombarded French Fleet at Oran in July 1940) , directed a radar-equipped cruiser, HMS Sheffield, and a succession of ASV-radar-equipped Swordfish biplanes from carrier HMS Ark Royal to shadow Bismarck while he prepared to launch a flight of Swordfish with torpedoes. The first flight of fourteen Swordfish mistakenly attacked HMS Sheffield, which only escaped destruction by resorting to violent maneuvers. The second flight of Swordfish (fifteen aircraft), firmly guided by Sheffield, attacked Bismarck at 8:47 P.M., launching thirteen torpedoes. Two hit, one amidships on the armor blister to no effect, the other all the way aft, wrecking Bismarck’s steering gear, propellers, and rudder, leaving her unmaneuverable.

From the contact reports of British aircraft intercepted by B-dienst and one message from Lütjens on Bismarck, Dönitz was able to plot the probable track of Bismarck and her pursuers. He directed the Bay of Biscay submarine trap, which had been reinforced by Rosenbaum’s U-73 but less Topp’s U-552, which did not sail (making a total of seven boats), to the most likely point of action and by the evening of May 26, notwithstanding the gale-whipped, raging seas, all were within a few miles of Bismarck and Force H. At 8:00 P.M. the carrier HMS Ark Royal and the battle cruiser HMS Renown of Force H, making high speed, nearly ran down one of the boats, Wohlfarth’s U-556. But Wohlfarth, serving as a “lookout,” had no torpedoes! In frustration he logged: “If only I had torpedoes now! I should not even have to approach, as I am in exactly the right position for firing. No destroyers and no zigzagging. I could get between them and finish them both off. The carrier has torpedo bombers on board. I might have been able to help Bismarck.” He reported the contact and shadowed, but the big ships faster than U-Boats soon outran him.

When Dönitz got word that Bismarck could not maneuver, he ordered all seven boats of the Biscay trap (including Gysae’s U-98, critically low on fuel and out of torpedoes) to converge on Bismarck and defend her. Gysae in U-98 and Wohlfarth in U-556 were to continue as “lookouts” and guide other U-boats to the enemy. Homing on Bismarck’s beacon signals, Rosenbaum in U-73 found her first, shortly after midnight May 27. Bismarck was then under torpedo attack by a flotilla of five Royal Navy destroyers, commanded by Captain Philip Vian in destroyer HMS Cossack (same one who captured German supply ship Altmark off Norway she had a Type 286 radar), responding to HMS Sheffield’s shadow reports. Rosenbaum observed and reported this destroyer action. Bismarck was not hit by destroyer torpedoes , neither she hit attacking destroyers but these constant destroyer attacks wore down her crew to a breaking point with fatigue. The hunt was almost over. The prey was tracked down. Now hunters were coming in for the kill.