CIO union loses plant guard case

…

U.S. State Department (February 4, 1945)

Livadia Palace, USSR

| Present | ||

|---|---|---|

| United States | United Kingdom | Soviet Union |

| President Roosevelt | Prime Minister Churchill | Marshal Stalin |

| Secretary Stettinius | Foreign Secretary Eden | Foreign Commissar Molotov |

| Mr. Byrnes | Sir Archibald Clark Kerr | |

| Mr. Harriman | Major Birse | Mr. Vyshinsky |

| Mr. Bohlen | Mr. Gromyko | |

| Mr. Pavlov |

Yalta, February 4, 1945, 8:30 p.m.

Top secret

Before dinner and during the greater part of the dinner the conversation was general and personal in character. Marshal Stalin, the President and the Prime Minister appeared to be in very good humor throughout the dinner. No political or military subjects of any importance were discussed until the last half hour of the dinner when indirectly the subject of the responsibility and rights of the big powers as against those of the small powers came up.

Marshal Stalin made it quite plain on a number of occasions that he felt that the three Great Powers which had borne the brunt of the war and had liberated from German domination the small powers should have the unanimous right to preserve the peace of the world. He said that he could serve no other interest than that of the Soviet state and people but that in the international arena the Soviet Union was prepared to pay its share in the preservation of peace. He said that it was ridiculous to believe that Albania would have an equal voice with the three Great Powers who had won the war and were present at this dinner. He said some of the liberated countries seemed to believe that the Great Powers had been forced to shed their blood in order to liberate them and that they were now scolding these Great Powers for failure to take into consideration the rights of these small powers.

Marshal Stalin said that he was prepared in concert with the United States and Great Britain to protect the rights of the small powers but that he would never agree to having any action of any of the Great Powers submitted to the judgment of the small powers.

The President said he agreed that the Great Powers bore the greater responsibility and that the peace should be written by the Three Powers represented at this table.

The Prime Minister said that there was no question of the small powers dictating to the big powers but that the great nations of the world should discharge their moral responsibility and leadership and should exercise their power with moderation and great respect for the rights of the smaller nations. (Mr. Vyshinski said to Mr. Bohlen that they would never agree to the right of the small powers to judge the acts of the Great Powers, and in reply to an observation by Air. Bohlen concerning the opinion of American people he replied that the American people should learn to obey their leaders. Mr. Bohlen said that if Mr. Vyshinski would visit the United States he would like to see him undertake to tell that to the American people. Mr. Vyshinski replied that he would be glad to do so.)

Following a toast by the Prime Minister to the proletariat masses of the world, there was considerable discussion about the rights of people to govern themselves in relation to their leaders.

The Prime Minister said that although he was constantly being “beaten up” as a reactionary, he was the only representative present who could be thrown out at any time by the universal suffrage of his own people and that personally he gloried in that danger.

Marshal Stalin ironically remarked that the Prime Minister seemed to fear these elections, to which the Prime Minister replied that he not only did not fear them but that he was proud of the right of the British people to change their government at any time they saw fit. He added that he felt that the three nations represented here were moving toward the same goal by different methods.

The Prime Minister, referring to the rights of the small nations, gave a quotation which said: “The eagle should permit the small birds to sing and care not wherefor they sang.”

After Marshal Stalin and the President had departed the Prime Minister discussed with Mr. Eden and Mr. Stettinius further the voting question in the Security Council. The Prime Minister said that he was inclined to the Russian view on voting procedure because he felt that everything depended on the unity of the three Great Powers and that without that the world would be subjected to inestimable catastrophe; anything that deserved [preserved?] that unity would have his vote. Mr. Eden took vigorous exception to the Prime Minister and pointed out that there would be no attraction or reason for the small nations to join an organization based on that principle and that he personally believed it would find no support among the English public. The Prime Minister said that he did not agree in the slightest with Mr. Eden because he was thinking of the realities of the international situation.

In reply to an inquiry of the Prime Minister in regard to the American proposal to the solution of the voting question, Mr. Bohlen remarked that the American proposal reminded him of the story of the Southern planter who had given a bottle of whiskey to a Negro as a present. The next day he asked the Negro how he had liked the whiskey, to which the Negro replied that it was perfect. The planter asked what he meant, and the Negro said if it had been any better it would not have been given to him, and if it had been any worse, he could not have drunk it.

Soon thereafter the Prime Minister and Mr. Eden took their departure, obviously in disagreement on the voting procedure on the Security Council of the Dumbarton Oaks organization.

Sunday, February 4, 1945

Marshal Stalin and his party arrived early this morning. They came down from Moscow by rail to a point in the Crimea and from there motored to Koreiz Villa, about 6 miles south of Livadia, where they made their headquarters during the Crimea Conference.

1100: The President conferred with Mr. Stettinius, Mr. Harriman, Admiral Leahy, General Marshall, Admiral King, General Kuter, General McFarland, Mr. Matthews (H. Freeman Matthews, Director of Office of European Affairs, State Department), Mr. Hiss (Alger Hiss, Special Assistant to the Secretary of State) and Mr. Bohlen (Charles E. Bohlen, Special Assistant to the Secretary of State). The conference was held in the grand ballroom of Livadia.

1615: Marshal Stalin and Mr. Molotov called at Livadia and conferred with the President in his study. Mr. Bohlen and Mr. Pavlov were also present.

1630: The President conferred with Mr. Hopkins, Mr. Matthews and Mr. Bohlen in his study.

1710: The First Formal Meeting of the Crimea Conference was convened in the grand ballroom of Livadia. Present:

| For the U.S. | For Great Britain | For the USSR |

|---|---|---|

| The President. | The Prime Minister. | Marshal Stalin. |

| Mr. Stettinius. | Mr. Eden. | Commissar Molotov. |

| Admiral Leahy. | Field Marshal Brooke. | Admiral Kuznetsov. |

| General Marshall. | Air Marshal Portal. | Col. General Antonov. |

| Admiral King. | Field Marshal Alexander. | Air Marshal Khudyakov. |

| Mr. Harriman. | Mr. Vyshinski. | |

| General Deane. | Admiral Cunningham. | Mr. Maisky. |

| General Kuter. | General Ismay. | Mr. Gousev. |

| General McFarland. | Major Birse. | Mr. Gromyko. |

| Mr. Pavlov. |

This meeting adjourned at 1950.

2030: The President was host at dinner at Livadia to the Prime Minister, Marshal Stalin, Mr. Stettinius, Mr. Eden, Mr. Molotov, Mr. Harriman, Mr. Clark Kerr, Mr. Gromyko, Mr. Vyshinski, Justice Byrnes, Major Birse, Mr. Bohlen and Mr. Pavlov. The menu included: Vodka, five different kinds of wine, fresh caviar, bread, butter, consommé, sturgeon with tomatoes, beef and macaroni, sweet cake, tea, coffee and fruit.

The American people rejoice with me in the liberation of your capital.

After long years of planning, our hearts have quickened at the magnificent strides toward freedom that have been made in the last months – at Leyte, Mindoro, Lingayen Gulf, and now Manila.

We are proud of the mighty blows struck by Gen. MacArthur, our sailors, soldiers, and airmen; and in their comradeship-in-arms with your loyal and valiant people who in the darkest days have not ceased to fight for their independence. You may be sure that this pride will strengthen our determination to drive the Jap invader from your islands.

We will join you in that effort – with our armed forces, as rapidly and fully as our efforts against our enemies and our responsibilities to other liberated peoples permit. With God’s help we will complete the fulfillment of the pledge we renewed when our men returned to Leyte.

Let the Japanese and other enemies of peaceful nations take warning from these great events in your country; their world of treachery, aggression, and enslavement cannot survive in the struggle against our world of freedom and peace.

U.S. State Department (February 5, 1945)

Livadia Palace, USSR

| Present | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fleet Admiral Leahy | Rear Admiral McCormick | |

| General of the Army Marshall | Rear Admiral Duncan | |

| Fleet Admiral King | Brigadier General Roberts | |

| Major General Kuter | Brigadier General Bessell | |

| Lieutenant General Somervell | Brigadier General Everest | |

| Vice Admiral Cooke | Brigadier General Lindsay | |

| Major General Bull | Commodore Burrough | |

| Major General Deane | Colonel Peck | |

| Major General Anderson | Colonel Lincoln | |

| Major General Hull | Captain Stroop | |

| Major General Wood | Captain McDill | |

| Major General Hill | Commander Clark | |

| Secretariat | ||

| Brigadier General McFarland | ||

| Captain Graves |

Yalta, February 5, 1945, 10 a.m.

Top secret

The Joint Chiefs of Staff: Agreed to recommend approval of the conclusions of the Minutes of the 185th Meeting of the Combined Chiefs of Staff and the approval of the detailed record of the meeting subject to later minor amendments.

Admiral Leahy said that this was a memorandum from the British Chiefs of Staff which proposed that the Combined Chiefs of Staff complete all of their unfinished business at MAGNETO and abandon the plan to return to Malta. The suggestion was open to discussion.

General Marshall said that the proposal was agreeable to him as the next best thing to do. He preferred to have the United States Shipping Representatives sent to MAGNETO to complete their studies and, if necessary, to detach the necessary number from this place to provide space.

General Somervell explained that the point at issue was the agreement on a planning date for the end of the war with Germany. The dates of 1 April, 1 July, and 1 November had already been considered, but it was necessary to settle on one date. He suggested that an agreement be reached with the British on the date of 1 July for planning purposes. The only possible complication in such an arrangement would be the introduction of some other operation which would change planning.

Admiral King said that Russian concurrence should be obtained on the planning date.

General Marshall suggested that the course of action should be as follows:

a. Obtain Russian concurrence to a planning date of 1 July 1945 for the end of the war with Germany, and

b. Detach a suitable number of personnel from MAGNETO to make room for the shipping personnel ordered from CRICKET to complete the shipping studies at this place.

After further discussion, the Joint Chiefs of Staff:

a. Agreed to seek Russian concurrence on the date of 1 July 1945 as the date of the collapse of Germany.

b. Agreed to accept the proposals of the British Chiefs of Staff contained in their memorandum of 4 February 1945 and directed the Secretaries to take necessary action.

Reference: SCAF 198

Admiral Leahy said that this subject had been under consideration by the United States and British Chiefs of Staff in Washington. JCS 577/26 was the report of the Joint Logistics Committee on its own initiative, recommending the acceptance of the British proposal subject to certain amendments set forth in Appendix “A” of this paper.

General Marshall explained that JCS 577/26 is the last of a long series of papers pertaining to the controversy with the British concerning the Bremen-Bremerhaven area. General Macready wrote a letter to Mr. McCloy on 20 January offering an agreement. Mr. McCloy wrote a letter back saying that this agreement was acceptable providing its meaning was in accordance with specifications which he named.

The Joint Logistics Committee in this paper has proposed a 4¼ page memorandum to the British in which the argument is somewhat unbending and proposes an agreement which amounts to amending General Macready’s proposal to include Mr. McCloy’s interpretations. Mr. McCloy’s letter is not attached to the paper.

Failure to reach agreement on this paper is holding up the protocol on the zones of occupation in Germany. In an effort to make more certain that this controversy will be halted, it is recommended that the action adopted be substituted for the proposal by the Joint Logistics Committee. This action consists of a presentation to the British of a short memorandum, with the draft agreement proposed by the JLC, and General Macready’s letter to Mr. McCloy.

General Marshall then distributed copies of the memorandum to be presented to the British in lieu of the memorandum proposed by the Joint Logistics Committee.

After further discussion, the Joint Chiefs of Staff: Agreed to present to the Combined Chiefs of Staff the memorandum proposed by General Marshall, with the draft agreement proposed by the Joint Logistics Committee and General Macready’s letter to Mr. McCloy attached thereto (Subsequently circulated as CCS 320/35).

Admiral Leahy said that in the papers under consideration the Joint Staff Planners recommend memoranda bearing on the war against Japan to be presented to the Soviet General Staff. He questioned whether the Russians would understand the memoranda when they received them.

Admiral Duncan explained that the memorandum embodied in JCS 1176/11 had to do with a special U.S. planning staff in Moscow and would be understood by the Russians.

General Deane explained further that this planning group had already had one meeting with the Russian Staff in Moscow previous to this conference and this memorandum was intended to facilitate the work of the planning group. There has been delay in the work of the reconnaissance party mentioned therein due to the fact that some Japanese had been allowed to remain in Kamchatka. As soon as they have been removed the American planning staff would be permitted to travel in that territory. He suggested that the memorandum be approved and handed to the Russians at a bilateral meeting which he felt was necessary. He recommended further that the President should be asked to request from Marshal Stalin the Soviet answers to two questions of paramount importance. The basic question is whether the Russians will require a Pacific supply line. The next question concerns Soviet agreement to establishment of U.S. air forces in Eastern Siberia. These questions should be put to the Soviets and definite answers requested.

General Marshall agreed and recommended approval of the memorandum for transmission to the Russians, preliminary to a meeting with them. He recommended further that a memorandum be prepared for the President to present to Marshal Stalin as follows:

The following are two basic military questions to which the United States Chiefs of Staff would appreciate an early answer at this conference:

a. Once war breaks out between Russia and Japan, is it essential to you that a supply line be kept open across the Pacific to Eastern Siberia?

b. Will you assure us that United States air forces will be permitted to base in the Komsomolsk-Nikolaevsk or some more suitable area providing developments show that these air forces can be operated and supplied without jeopardizing Russian operations?

In reply to a question by General Marshall, General Deane said that the memorandum he had proposed was entirely satisfactory. He thought that after discussion of the two basic questions with the Russian Staff we should outline the main points and request the President to ask Marshal Stalin for a fiat approval or disapproval of them. The Russian Staff have already disapproved a U.S. move into Eastern Siberia and he felt that they would not change this decision without a direct approval from the highest level.

After further discussion, the Joint Chiefs of Staff:

a. Approved the recommendations of the Joint Staff Planners in JCS 1176/10 and 1176/11.

b. Agreed to send to the President the memorandum proposed by General Marshall, with a request that it be presented to Marshal Stalin.

Yusupov Palace, USSR

| Present | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | United Kingdom | Soviet Union | ||

| Fleet Admiral Leahy | Field Marshal Brooke | General of the Army Antonov | ||

| General of the Army Marshall | Marshal of the Royal Air Force Portal | Marshal of Aviation Khudyakov | ||

| Fleet Admiral King | Admiral of the Fleet Cunningham | Fleet Admiral Kuznetsov | ||

| Major General Kuter | ||||

| Vice Admiral Cooke | Field Marshal Alexander | |||

| Major General Deane | General Ismay | Lieutenant General Gryzlov | ||

| Major General Bull | Rear Admiral Archer | |||

| Major General Anderson | Vice Admiral Kucherov | |||

| Major General Hull | Commander Kostrinsky | |||

| Secretariat | Interpreters | |||

| Brigadier General McFarland | Captain Lunghi | |||

| Brigadier Cornwall-Jones | Captain Ware | |||

| Captain Graves | Lieutenant Chase | |||

| Commander Coleridge | Mr. Potrubach |

Leningrad, February 5, 1945, noon

Top secret

At the suggestion of General Antonov, Field Marshal Brooke agreed to take the chair.

Sir Alan Brooke suggested that the meeting should begin by considering the coordination of the Russian and U.S.-British offensives. At the Plenary Meeting on the previous day, General Antonov had put forward certain Russian requirements. He had asked, first, that during the month of February the Allied armies in the West should carry out offensives. As General Marshall had explained, the Allied offensive in the West would start in the North on the eighth of February and some eight days later the Ninth U.S. Army would also start an offensive. These operations would be carried out during most of February. In addition to these operations in the North, operations were now being carried out by United States and French armies to push the Germans back to the Rhine in the Colmar area. It was therefore clear that the immediate coordination of Allied and Russian offensives was already being carried out. It was necessary, however, to look into the matter of coordination of offensives in the spring and summer months. As far as operations in the West were concerned these would be more or less continuous throughout the spring. There were, of course, bound to be intervals between operations, though such intervals would not be of long duration. For instance, after clearing the western bank of the Rhine on the northern part of the front, preparations would have to be made for the final crossing of the Rhine. From a study of conditions of the river it was hoped to effect a crossing during the month of March. After establishing the crossing it would have to be widened and improved before the final advance into the heart of Germany could be undertaken.

Should operations in the North aimed at the Ruhr be held up, it was the intention to carry out further operations in the South. It was safe to say, therefore, that during the months of February, March and April, active operations would be in progress during almost the entire time.

The actual crossing of the Rhine presented the greatest difficulties and it was during the period of this crossing that the Allies were anxious to prevent a concentration of German forces against the armies in the West. It was therefore hoped that during March operations on the Eastern Front would be able to continue. Sir Alan Brooke said he appreciated the difficulties in March and early April due to the thaw and mud which would interfere with communications. He also realized that after their present great advances the Russian armies would want to improve their communications. He would much like to hear General Antonov’s views on what operations could be undertaken by the Soviet armies during March and April.

General. Marshall said that during the Tripartite Plenary Meeting on the previous day the number of divisions, the amount of artillery, and the number of tanks on the Eastern Front had been enumerated. In considering the Western Front it was important to bear in mind that operations must be conducted to meet the special conditions existing. In the West there was no superiority in ground forces. There were delicate lines of sea communications, particularly in the Scheldt Estuary. The Allies, however, did enjoy a preponderance of air power, but in this connection the weather was an important consideration. If the Allies were unable to take full advantage of their air superiority they did not have sufficient superiority on the ground to overcome enemy opposition. Operations must therefore be conducted on this basis. Another restriction arose from the fact that there were only a small number of favorable locations for crossing the Rhine. It was therefore most important to insure that the enemy could not concentrate strongly at the point of attack.

The enemy were now operating behind the Rhine and the Siegfried line and therefore had great freedom of maneuver. We must therefore arrange to occupy the Germans as much as possible to prevent them from concentrating against us on the very narrow bridgehead area available to us.

With regard to air forces, on the Western Front some 3,000 to 4,000 fighter-bomber sorties could be undertaken each day. There was about one-third of this strength on the Italian Front. This did not include the power of the great four-engine bombers with their escorting fighters.

General Antonov said that, as Marshal Stalin had pointed out, the Russians would continue the offensive in the East as long as the weather permitted. There might be interruptions during the offensive and, as Sir Alan Brooke had said, there was the need to reestablish Russian communications. The Soviet Army would, however, take measures to make such interruptions as short as possible and would continue the offensive to the limit of their capacity.

In connection with the western offensive in February, it was not believed that the Germans could transfer forces from the Eastern Front to the West in large numbers. The Soviet Staff, however, was also interested in the Italian Front, from where the Germans had the opportunity of transferring troops to the Eastern Front. In view of this, the Soviet General Staff would like to know the potentialities of the Allied armies now fighting the Germans in Italy.

Sir Alan Brooke said that the situation on the Italian Front was being carefully examined as it developed. Kesselring’s forces had now been driven into northern Italy where the country was very well suited for defense or for systematic retirement. There was a series of rivers which could be used for rear-guard actions while withdrawing his forces gradually. The enemy would have to retreat through the Ljubljana Gap or the passes of the Alps. The coast in the Bay of Venice was not suitable for amphibious operations, and therefore outflanking operations in the Adriatic did not appear fruitful. So far there had been continuous offensive operations which had driven the enemy out of the Apennine line and into the Valley of the Po. Winter weather and floods had, however, brought these offensive operations almost to a standstill.

At present our troops were preparing for further offensive action when the weather improved. It had, however, been decided that it would be better to transfer some of the forces now in Italy to the Western Front, where at present we did not have sufficient superiority in ground forces. Five divisions were therefore now to be transferred from Italy to France and certain air forces would accompany them. The forces remaining in Italy had been instructed to carry out offensive operations and to seize every opportunity to inflict heavy blows on the enemy. Their object was to retain as many of Kesselring’s forces as possible by offensive action. However, owing to the topography of the country, it was believed that Kesselring could carry out a partial withdrawal without the Allies being able to stop it. The rate of withdrawal was estimated at some one and one-half divisions per week. Thus, any withdrawal which he did undertake could only be gradual.

To sum up, it was proposed to take what action was possible to stop the German withdrawal in Italy, though it was not thought that this could be entirely prevented. For this reason, it had been decided to withdraw certain forces from Italy to the vital front in Northwest Europe.

General Marshall said that he agreed with Sir Alan Brooke’s summary of the position but felt that a reference should be made to the value of our air power in Italy.

General Antonov asked the number of German troops believed to be in Italy.

Field Marshal Alexander said that at present the German forces in Italy consisted of 27 German divisions and 5 Italian divisions.

Sir Alan Brooke said that all these forces could not be held down in Italy by offensive action. If the Germans decided to retire to the line of the Adige, it was estimated that they would be able to withdraw some ten divisions from Italy.

Sir Charles Portal said that on the Western and Italian Fronts together the United States and British air forces consisted of some fourteen thousand aircraft. This figure did not include the reserve behind the front line. Should the land campaign have to halt, the war in the air would continue, so far as weather permitted, even more strongly than before. Everything possible would be done, as General Marshall had stated, to bring the greatest possible air assistance to the vital points of attack in the land offensive. Such air assistance included the operations of a number of airborne divisions, for which the necessary transport was available.

So far as the requirements of the land battle permitted, it was the intention to concentrate the strategic bomber forces on the enemy’s oil supply. Evidence was available almost daily that the destruction of his oil production capacity was imposing limitations on the enemy’s operations. It was believed that the destruction of enemy oil was the best contribution which the air forces could make, both to the offensive on land and in the air. Much had been done and would continue to be done to disorganize the enemy’s rail communications, but it was our experience that an attempt to cut all railways in the middle of Germany to stop troop movements would produce disappointing results in view of the relative ease with which the enemy could repair such destruction.

It was known that the Germans intended to assemble a strong force of jet-propelled fighters during the course of the present year. It had therefore been decided that, in order to maintain our air superiority into the summer, a proportion of our air effort must be devoted to attacks on the German jet-propelled fighter manufacturing plants. Nevertheless, it was an agreed principle that when the land offensive began, everything in the air that could contribute to its success should be so used.

Before the advance of the Soviet armies, Allied air power had been brought to bear as far afield as Koenigsberg, Danzig, Posen and Warsaw. The great range of our strategic air forces made it most necessary that Allied air operations should be coordinated with the advance of the Soviet armies both to prevent accidents and to obtain the best value from our bomber effort.

General Marshall invited Field Marshal Alexander to comment on the capability of air forces in Italy to prevent a German withdrawal.

Field Marshal Alexander said that it had been his experience in Italy that our greatly superior air forces were a most powerful weapon while the enemy was withdrawing, if it was possible to force the pace of his withdrawal. If, however, he was in a position to withdraw at his own pace the air forces were less effective since the withdrawal could be undertaken mostly under cover of darkness.

In the Valley of the Po there was a series of extremely strong holding positions and it would therefore be difficult to force the enemy to withdraw faster than he planned. Nevertheless, when the weather improved from May onwards, considerable damage could be done to the withdrawing German forces and to their lines of communication. However, in February, March and April the weather was bad, with low clouds, which hindered the air effort to a great extent. Further, the Germans had destroyed nearly all the bridges over the River Po and had replaced them with some 30 to 40 pontoon bridges which were not kept in position during the day but were hidden along the banks. The destruction of these bridges was therefore extremely difficult.

To sum up, the better the weather the more damage could be done to the enemy by air action but however successful the air action, he did not believe that it would be possible entirely to prevent a German withdrawal by this means.

General Marshall said that at the Tripartite Plenary Meeting on the previous day the desire had been expressed that every effort should be made to stop the movement of German forces from west to east by air action and, in particular, to paralyze the vital rail junctions of Berlin and Leipzig. In this connection a report he had received that day summarizing Allied air operations in the last few days was of interest. On Friday, the second of February, the Royal Air Force had flown 2,400 sorties, concentrating on rail and road targets in Euskirchen and Coblenz. The latter, in particular, was of vital importance in the transfer of German forces to the East. Similar destruction of rail targets had taken place east of Alsace. On the same night a thousand of our bombers had attacked Wiesbaden, Karlsruhe and synthetic oil plants elsewhere. On the following day, Saturday, the third of February, four-engined United States bombers had attacked Marienberg railway yards and 550 RAF bombers had attacked targets in the same area.

In relation to the destruction of communications and the interference with enemy movements the following data had been received relating to the effect of air attacks carried out on the 22nd and 23rd of January: On these two days alone 2,500 motor cars and trucks had been destroyed and 1,500 damaged; a thousand railway cars had been destroyed and 700 damaged; 93 tanks and self-propelled guns had been destroyed and a further 93 damaged; 25 locomotives had been destroyed and 4 damaged; 50 horse-drawn vehicles had been destroyed and 88 damaged. In addition, 62 known gun positions had been wiped out and 21 marshalling yards damaged. These very large results had been obtained on the two days he had referred to, but similar attacks were carried out on almost every fine day by the Allied air forces. He had referred on the previous day to the thousand-bomber attack on Berlin carried out on the third of February. There was also ready a plan to carry out a similar attack on Leipzig.

Marshal Khudyakov said that, as Marshal Stalin had pointed out, more than 8,000 Soviet planes were being used in the main thrust. In spite of weather conditions, between the 12th of January and the first of February 80,000 sorties had been flown in support of the Russian advance. More than a thousand enemy planes had been captured on airfields which had been overrun by the Russian troops. These aircraft had been prevented from flying away by bad weather. In addition, 560 planes had been shot down in air combat. If better weather prevailed air operations could be carried out on objectives further in the enemy rear but fog at this time of year rendered such deep operations to the west of Berlin almost impossible. He agreed with Sir Charles Portal that there were too many railroads in Germany to destroy all of them. He hoped that Field Marshal Alexander’s operations could be aimed at hampering the movement of German divisions from Italy to the Eastern Front.

Field Marshal Alexander said that this object was contained in his directive.

Marshal Khudyakov said that he was glad to hear of this. In Italy there were fewer railways to assist the enemy withdrawal.

Field Marshal Alexander explained that the Germans in Italy largely used roads for their withdrawals.

General Antonov said that in addition to the Soviet offensives in the North, offensives would also continue in the direction of Vienna and west of Lake Balaton. It was for this reason that Allied action in Italy was of importance to the Soviets. It seemed to him expedient that Allied land offensives should be directed toward the Ljubljana Gap and Graz. He now understood that this was not possible.

Sir Alan Brooke said that it must be remembered that the Allies had no great superiority in land forces. They had come to the conclusion that in conjunction with the vital death blows being dealt by the Soviet armies in the East, the correct place for the western death blow was in Northwestern Europe. For this reason, it had been decided to transfer divisions from Italy to the Western Front and to limit operations in Italy to holding as many German forces in that theater as possible. In the event of a German withdrawal from northern Italy, we had forces strong enough to take advantage of such a withdrawal, and possibly at a later date to be able to operate through the Ljubljana Gap. Such action, however, must remain dependent on the withdrawal of a proportion of the German forces at present in the north of Italy.

General Antonov said that the Germans were transferring forces from Norway to Denmark. He asked if there was any way in which such a movement could be stopped.

Sir Andrew Cunningham said as far as was known, these movements were being carried out by rail and road to Oslo and not by sea. The troops were then being moved across the short sea passage to Denmark. It was not possible in view of heavy mining to operate surface forces in the Skagerrak and thus prevent the enemy making this short sea passage.

Sir Charles Portal said that the action of the air forces in this connection could be divided into two parts: firstly, by such attacks as could be made on shipping in the Kattegat, and with four-engined bombers operated on almost every fine night in an endeavor to bomb enemy ships. Several ships had recently been set on fire in this area. The second form of air action was by minelaying aircraft. Approximately 1,000 mines were being laid by this method each month. Each aircraft carried some six mines. Sir Andrew Cunningham had just told him that recently these mines had sunk or damaged four enemy transports. German minesweepers did endeavor of course to sweep up our mines but it was now planned to increase the number of air attacks made on these minesweepers. However, there were so many varying tasks for the air forces to carry out that all could not be undertaken equally well.

Sir Alan Brooke said an examination had also been made of the possibility of stopping the movement of German forces from Norway by land action in Norway itself. There were, however, insufficient forces to undertake this without weakening our main effort on the Western Front.

General Antonov said he felt it would be interesting to exchange information with regard to the method of carrying out operations in the autumn, winter and spring when, by reason of weather, it was not always possible to make use of air power. On these occasions the role of artillery became one of particular importance. As Marshal Stalin had said on the previous day, the Russians were establishing special artillery divisions of some 300 to 400 guns each, which were used for breaking through the enemy line. This method enabled a mass of artillery of some 230 guns of 76 millimeters and upwards to be concentrated on a front of one kilometer. He would be very glad to know what degree of artillery density would be used on the Western Front when the February offensive commenced.

General Bull said that the northern army group, which would take part in the next offensive, possessed some 1,500 guns of 105 millimeters and upwards, and the United States Army group which would also take part in the offensive, had some 3,000 guns of similar calibers. The army commanders concerned, by concentrating their artillery power on a narrow front, would be able to use some 200 guns to the mile in the area of the break-through. To this offensive power should be added the power of the air forces. In the three days preceding the attack on the eighth of February, it could be expected that some 1,600 heavy bombers would be used, capable of delivering 4,500 tons of bombs on the first day. For the remaining two days before the offensive, a slightly less weight of bombs could be dropped, but closer to the point of attack. Not only would communications behind the front be bombed, but also positions known to be strongly held.

On the day of the attack itself, “carpet bombing” would be used, and some 4,000 tons could be dropped on an area two miles square. He felt the effect of the air attack and the artillery concentration should produce a breakthrough, thus allowing our armor to operate in the enemy’s rear. A similar pattern of attack had been used on previous occasions with great success.

Marshal Khudyakov asked what action would be taken if it was found that weather prohibited the air [forces.?] from operating on the day of attack.

General Bull explained that the attack was normally timed for a day on which it was predicted that the weather would enable “carpet bombing” to be carried out. During the actual attack the bombing was carried out some 2,000 yards ahead of our own front line, but earlier bombing on targets further behind the line could be undertaken through overcast.

Marshal Khudyakov explained that all Russian operations in winter were planned on the supposition that bad weather would exist, and no air operations would be possible. He felt that the Allies should bear this point in mind in planning their own operations.

General Marshall said that he had endeavored to explain that the Allies did not possess the same superiority in ground forces as did the Russians. The Allies did not have 300 divisions, nor was it possible to produce them. It was therefore essential to make full use of our air superiority. He would like to point out the advance across France had, in fact, been accomplished with the same number of divisions as the enemy himself had. This was made possible by a combination of ground and airpower.

General Antonov said that he now had a very clear picture of Allied offensive intentions. Were there any questions which the British or United States Chiefs of Staff would like to ask?

Admiral Leahy said that in view of the very frank discussion of plans which was taking place, he would like to bring up the question of liaison between the Eastern and Western Fronts. The distance between the two armies was now so short that direct liaison was a matter of great importance. He had been directed by the President to bring up this question of liaison before the British, Russian and United States Chiefs of Staff. It was the opinion of the United States Chiefs of Staff, who had not yet discussed it with their British colleagues, that arrangements should be made for the Allied armies in the West to deal rapidly with the Soviet commanders on the Eastern Front through the Military Missions now in Moscow. He would be glad to take back to the President the views of the Soviet and British Chiefs of Staffs on this matter.

Sir Alan Brooke said that the British Chiefs of Staff were equally anxious to have the necessary liaison in order that plans could be concerted. They felt that such liaison required organizing on a sound basis. Military Missions were already established in Moscow, and these should, he felt, act as a link on a high level between the United States, British, and Soviet Chiefs of Staffs. In addition to this, closer liaison was required between the commanders of Allied theaters with the commanders of the nearest Russian armies. For example, on the Italian Front, Field Marshal Alexander required direct liaison with the Russian commander concerned.

In the case of the Supreme Commander on the Western Front, he would require direct liaison with the commanders of the Russian, armies in the East. Thus, there would be coordination between the high commands dealing with future action and in addition, direct coordination between the Allied and Soviet armies, who were closely in contact, on such matters as the employment of air forces and the coordination of day-to-day action.

General Antonov said that the question of liaison between the general staffs was very important and, as had already been mentioned, could be undertaken through the Missions in Moscow. In the present state of the offensives, this should be perfectly satisfactory until the forces came closer into contact with each other. Later, as operations advanced, the question of liaison between Army commanders could be reviewed and adjusted. These proposals would be reported to Marshal Stalin.

General Marshall said that he had not entirely understood the necessity for limiting liaison.

General Antonov explained that his proposal was to limit liaison to that through the General Staff in Moscow and the U.S. and British Missions. Such arrangements, however, could be revised and adjusted later to meet changing conditions.

General Marshall pointed out that difficulties and serious results had already occurred in air operations from Italy over the Balkans. Such operations were directed from day to day and even from hour to hour, depending on weather and other conditions. If contact had to be maintained between the armies concerned through Moscow, difficulties would be certain to arise.

If this roundabout method of communications through many busy people had to be adopted, there was a risk that our powerful air weapon could not be properly used.

General Antonov said that the accident to which General Marshall referred had occurred not because of lack of liaison but due to the pilots concerned losing their way. They had, in fact, made a navigational mistake with regard to the correct point for bombing.

General Marshall said that he recognized this. However, the bombline at that time excluded roads crowded with retreating Germans who could not be bombed by the Allied forces without an approach being made through Moscow. A powerful air force was available and good weather existed but the Allied air force was unable to act and the Germans profited thereby.

Sir Alan Brooke said he entirely agreed with General Marshall that, through lack of liaison, we are losing the full force of the air power at our disposal.

General Antonov said that at the present time no tactical coordination was required between Allied and Russian ground forces. We should, he believed, aim at planning the strategic requirements of our air forces. The use of all Soviet air forces was dictated by the Soviet General Staff in Moscow. It was for this reason that the coordination of the air effort should, in his view, be carried out through the Soviet General Staff in Moscow, who alone could solve the problems. It was possible to agree on the objectives for strategic bombing irrespective of a bombline.

Sir Charles Portal said that in the British view there were two distinct problems with regard to liaison. The first was the necessity for the form of liaison referred to by General Antonov, i.e., the coordination of the Allied long-range bomber effort over eastern Germany and its relation to the advance of the Red Army. The Allied long-range strategic bomber force was not controlled by the Supreme Commander in the West except when it was undertaking work in close cooperation with the ground forces but was controlled by the United States and British Chiefs of Staff. It was right, therefore, that the United States and British Chiefs of Staff or their representatives should deal direct with Moscow on this matter.

The second problem was in respect to the constant air operations out from Italy in relation to Russian operations in the Balkans and Hungary. In that theater liaison was required, not so much on policy as on an interchange of information. The British Chiefs of Staff entirely agreed with the United States view that it was inefficient for liaison between Field Marshal Alexander and the Russian commanders to be effected through Moscow. It was, therefore, essential that some machinery should be set up to deal with day-to-day liaison between General Alexander and the Russian headquarters which controlled the southern front. Without such direct liaison it was impossible to take advantage of the many opportunities presented to hit the Germans from the air.

Marshal Khudyakov said that concerning air action into Germany itself, this could be done through the General Staff in Moscow as suggested by Sir Charles Portal, using the U.S. and British Military Missions. This liaison on policy was one which took time to arrange and was not a matter for great speed. With regard to direct liaison between Field Marshal Alexander and the Russian left wing he felt this was a matter which should be reported to Marshal Stalin.

General Antonov asked if it could not be agreed that a bombline should be established running from Berlin to Dresden, Vienna and Zagreb, all these places being allotted to the Allied air forces. Such a line could, of course, be changed as the front changed.

Admiral Leahy and Sir Alan Brooke asked that this matter be deferred one day for consideration.

Admiral Kuznetsov asked if plans had been made for any naval operations in direct assistance to the land attack which was shortly to be carried out. He referred not so much to the normal naval operations in the defense of communications and day-to-day operations of the fleet to control the seas but rather to direct operations in support of a land offensive.

Sir Andrew Cunningham explained that projected operations were too far inland to be directly affected by any operations which could be carried out by the fleet except the routine operations of keeping open communications. He asked if Admiral Kuznetsov had any particular operations in mind.

Admiral Kuznetsov said he had no particular operation in mind but rather the possibility of some operation in the neighborhood of Denmark that would not have any direct tactical connection with the army operations but would have a strategic connection.

Sir Andrew Cunningham said that possible operations to outflank the Rhine had been studied. However, landing on the coast of Holland would prove extremely difficult and the necessary land forces were not available to enable an operation against Denmark to be undertaken.

Sir Alan Brooke said that owing to the difficulty of forcing a crossing of the Rhine when that river was in flood, a very detailed examination had been carried out of the coastline from the Scheldt to the Danish coast, but operations in this area had not been found practicable since: firstly, large areas of Holland could be flooded and, secondly, operations further to the north would be too far detached from the main thrust to be of value.

Admiral King asked if Admiral Kuznetsov would outline the successes which the Soviet Fleet had been able to obtain in amphibious operations or operations to interfere with the transport of troops from the Baltic states to Germany.

Admiral Kuznetsov said that operations of the Soviet Fleet to cut German communications in the Baltic had been undertaken by submarines and naval aircraft. When the area of Memel was reached, it became possible to transfer torpedo boats to augment Russian naval activity in that area. However, all operations were at present hampered by ice conditions and, further, the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga were heavily mined by the enemy, and mine clearance was hampered by weather conditions and ice.

Admiral King said that he appreciated that ice conditions were now limiting operations but had asked this question in view of earlier Soviet communiqués mentioning the damage or destruction of German shipping.

Admiral Kuznetsov said that the earlier destruction of German shipping had been carried out by naval air forces and submarines.

Admiral Leahy said that the United States Chiefs of Staff were engaged in making logistic plans for that phase of the war following the collapse of Germany. It had been suggested that such plans should now be based on a probable date of the first of July for the earliest possible collapse of Germany. Before deciding on such a date, he was anxious to have the views of the Soviet Staff on this matter.

General Antonov said that until the eastern and western offensives developed it was difficult if not impossible to predict the date of the collapse of Germany.

Admiral Leahy said he entirely appreciated the uncertainty but for planning purposes he would be glad to know if the Soviet Staff regarded the first of July as the earliest date as a reasonable assumption.

General Antonov said he regarded such assumptions as being difficult to make. He could assure Admiral Leahy that the Soviet General Staff would concentrate every effort on the earliest possible defeat of Germany.

General Marshall explained that a year ago it had been necessary to assume a date for the defeat of Germany on which to base calculations on such matters as production and the construction of shipping. It was necessary to revise this date from time to time, particularly in connection with the handling of shipping throughout the world. It had been proposed to take two target dates, one the earliest and one the latest likely date for the defeat of Germany. Such dates were now under consideration between the United States and British Chiefs of Staff who were in agreement that the first of July was the earliest likely date but differed by two months with regard to the latest likely date. The United States assumption in this connection was the 31st of December. Did General Antonov regard the first of July as improbable as the earliest likely date?

General Antonov said that he regarded the summer as the earliest date and the winter as the latest. The first of July should be a reasonably certain date for the defeat of Germany if all our efforts were applied to this end.

A brief discussion took place on future business.

Sir Alan Brooke suggested that a meeting should be held on the following day at 12 noon in the Soviet Headquarters, and that the following subjects should be discussed: (1) Coordination of Air Operations; (2) Shuttle Bombing; and (3) A Short Discussion on the War in the Far East.

Admiral King said he would be prepared to make a statement on operations taking place in the Pacific and his conception of the future development of the war in that theater. He would welcome any questions which the Soviet Staff might wish to ask on this subject.

General Antonov said he would be glad to listen to a description of the situation in the Far East and operations in that area, but as far as discussion of the matter was concerned the Soviet General Staff would prefer that this should take place after the war in the Far East had been considered by the Heads of Government.

Oberdonau-Zeitung (February 5, 1945)

Sechs Millionen Arbeitssklaven für Sibirien – Das würde unser Schicksal sein!

…

Salzburger Zeitung (February 5, 1945)

Es wird unseren Feinden nicht gelingen, das deutsche Volk von seiner Führung zu trennen

…

Führer HQ (February 5, 1945)

In Ungarn wurden südlich des Velencesees feindliche Angriffe bis auf geringe Einbrüche abgewehrt. Nördlich Stuhlweißenburg und im Nordteil des Vértesgebirges warfen unsere Truppen den Feind nach Osten zurück. Die tapfere Besatzung von Budapest wurde in ihrem schweren Kampf durch deutsche Jagd- und Schlachtflieger fühlbar entlastet.

Im südlichen Grenzgebiet der Slowakei sowie zwischen den Westbeskiden und der Oder scheiterten zahlreiche Angriffe der Bolschewisten. Beiderseits Brieg trat der Gegner aus seinen Oderbrückenköpfen mit starken Kräften zum Angriff an. Schwere Kämpfe sind hier im Gange.

An der übrigen Oderfront hat sich die Lage nicht wesentlich verändert. Gegen den Verteidigungsring von Frankfurt an der Oder sowie gegen Küstrin und Posen setzten die Sowjets ihre heftigen Angriffe fort, ohne nennenswerte Erfolge zu erzielen.

Im südlichen Pommern wehrten unsere Verbände zwischen Pyritz, Deutsch-Krone und im Raum nordwestlich Jastrow erneute feindliche Angriffe ab. Die Marienburg und die Stadt Elbing stehen im Brennpunkt erbitterter Kämpfe.

In Ostpreußen blieb den mit überlegenen Kräften bei Wormditt, Bartenstein und beiderseits Königsbergs anstürmenden Bolschewisten der Durchbruch dank der Tapferkeit unserer Truppen und ihrer Führung versagt. 53 Panzer und 63 Geschütze wurden vernichtet.

Deutsche Seestreitkräfte griffen wiederholt in die Kämpfe an der ostpreußischen Küste ein und brachten den Verbänden des Heeres Entlastung.

In Kurland flaute die Kampftätigkeit infolge der hohen Verluste des Feindes an den Vortagen ab.

Schlachtflieger, unterstützt von Jägern, griffen mit guter Wirkung in die Erdkämpfe in Ungarn, in Schlesien und in der Neumark ein. Insgesamt wurden gestern durch die Luftwaffe im Osten 73 Panzer, 44 Geschütze außer Gefecht gesetzt, über 900 Fahrzeuge vernichtet und 26 Flugzeuge zum Absturz gebracht.

Im Westen dauern vor der Rurfront die feindlichen Bewegungen und starkes Artilleriefeuer an.

Im Gebiet von Schleiden brachten unsere Truppen die amerikanischen Durchbruchsversuche vor der Urftalsperre wieder zum Stehen und zerschlugen südlich davon weiterer Angriffe. In den südwestlichen Ausläufern der Schnee-Eifel konnte der Gegner in eine Bunkergruppe eindringen, blieb dann jedoch im Abwehrfeuer liegen.

Die Eckpfeiler unseres Brückenkopfes im oberen Elsass waren auch gestern starken feindlichen Angriffen ausgesetzt. Die in der Rheinebene zwischen Breisach und Kolmar angreifenden Amerikaner wurden nördlich Neubreisach abgewiesen, südlich Kolmar nach geringem Vordringen wieder aufgefangen. 14 feindliche Panzer wurden dabei vernichtet. Im Raum nördlich Mülhausen stehen unsere Truppen in heftigen Abwehrkämpfen vor Ensisheim und Sulz.

Der Artilleriekampf um Dünkirchen und Lorient hat sich verstärkt.

In den gestrigen Abendstunden warfen britische Terrorverbände Bomben auf mehrere Orte in Westdeutschland. Besonders in den Wohnvierteln von Bonn und Godesberg entstanden Schäden.

Das Vergeltungsfeuer auf London dauert an.

Im Monat Jänner verloren die Anglo-Amerikaner durch Jäger und Flakartillerie der Luftwaffe 1.389 Flugzeuge, in der Mehrzahl viermotorige Bomber.

In hartem Kampf gegen den feindlichen Nachschub torpedierten unsere Unterseeboote in den Gewässern um England 7 Schiffe mit 54.400 BRT und 2 Geleitfahrzeuge. Das Sinken von 3 Frachtern mit über 13.000 BRT und einem Bewacher wurde beobachtet. Mit dem Untergang weiterer Schiffe, unter denen sich ein 20.000 BRT großer Truppentransporter befand, ist zu rechnen.

In Schlesien haben seit dem 14. Jänner zahlreiche Volkssturmbataillone, insbesondere im oberschlesischen Industriegebiet, den feindlichen Ansturm bis zum Eintreffen der Reserven des Heeres und der Waffen-SS aufgehalten und damit durch ihre vorbildliche Einsatzbereitschaft und Tapferkeit entscheidenden Anteil an dem Aufbau einer gefestigten Abwehrfront.

Supreme HQ Allied Expeditionary Force (February 5, 1945)

FROM

(A) SHAEF MAIN

ORIGINATOR

PRD, Communique Section

DATE-TIME OF ORIGIN

051100A February

TO FOR ACTION

(1) AGWAR

(2) NAVY DEPARTMENT

TO (W) FOR INFORMATION (INFO)

(3) TAC HQ 12 ARMY GP

(4) MAIN 12 ARMY GP

(5) AIR STAFF

(6) ANCXF

(7) EXFOR MAIN

(8) EXFOR REAR

(9) DEFENSOR, OTTAWA

(10) CANADIAN C/S, OTTAWA

(11) WAR OFFICE

(12) ADMIRALTY

(13) AIR MINISTRY

(14) UNITED KINGDOM BASE

(15) SACSEA

(16) CMHQ (Pass to RCAF & RCN)

(17) COM ZONE

(18) SHAEF REAR

(19) AFHQ for PRO, ROME

(20) HQ SIXTH ARMY GP

(REF NO.)

NONE

(CLASSIFICATION)

IN THE CLEAR

Allied forces northeast of Monschau gained up to 3,000 yards to reach the edge of Rührberg, and our infantry advanced 3,500 yards to the south shore of the Urftstausee, the large lake formed by the Urft River Dam. Southwest and south of the lake, we have cleared the enemy from the towns of Einruhr, Wollseifen and Morsbach, and have pushed one-half mile east of Morsbach.

Southeast of Monschau, in the vicinity of Hollerath, we have encountered rifle and machine gun fire from enemy pillboxes, and a number of pillboxes just west of the town have been neutralized. In the area two miles southeast of Udenbreth, a group of enemy infantry forming for a counterattack was dispersed by our artillery.

Roth, 11 miles northeast of St. Vith, has been cleared of the enemy, and our infantry elements have advances into the Schneifel Forest east of Buchet.

On the eastern edge of the Hardt Mountains we entered Rothbach, inflicted casualties and took prisoners. Then, we withdrew to positions southwest of the town.

Near the Rhine in the Haguenau area, fighting continued in Oberhöfen. Farther east, advances were made in the Drusenheim Forest, northeast of Rohrwiller.

In the Colmar sector, Wolfgantzen, one mile west of Neuf-Brisach, was cleared after hard fighting, and mopping up was in progress in Biesheim to the north. South and west of Colmar, the towns of Obermorschwihr, Voegtlinshoffen, Turckheim and Labaroche were liberated.

Farther south, Cernay was completely cleared while Steinbach and Uffholtz in the same area were occupied.

East of Cernay, we crossed the Thür River near Staffelfelden, which was occupied. The advance here reached Berrwiller, two miles northwest of Staffelfelden.

Weather curtailed air operations yesterday, however fighter bombers strafed enemy motor transport and troops in the Colmar area, hit the railway bridge at Breisach and bombed targets in Bremgarten and Grissheim, villages on the German side of the Rhine southeast of Breisach.

Other fighter-bombers attacked railway yards at Offenburg, Rottweil, Donaueschingen and Steig.

Last night, heavy bombers in strength, were over Germany with Bonn as the main objective. Light bombers attacked road and rail targets over a wide area in western Germany.

COORDINATED WITH: G-2, G-3 to C/S

THIS MESSAGE MAY BE SENT IN CLEAR BY ANY MEANS

/s/

Precedence

“OP” - AGWAR

“P” - Others

ORIGINATING DIVISION

PRD, Communique Section

NAME AND RANK TYPED. TEL. NO.

D. R. JORDAN, Lt Col FA2409

AUTHENTICATING SIGNATURE

/s/

U.S. State Department (February 5, 1945)

Yusupov Palace, USSR

| Present | ||

|---|---|---|

| United States | United Kingdom | Soviet Union |

| Secretary Stettinius | Secretary Eden | Foreign Commissar Molotov |

| Mr. Byrnes | Sir Alexander Cadogan | |

| Mr. Harriman | Sir Archibald Clark Kerr | Mr. Vyshinsky |

| Mr. Page | Major Theakstone | Mr. Maisky |

| Mr. Gromyko | ||

| Mr. Gusev | ||

| Mr. Pavlov |

Leningrad, February 5, 1945, 1:30 p.m.

Top secret

Mr. Molotov opened the luncheon by proposing a toast to the leaders of the three countries. Upon being informed by Mr. Harriman that Manila had been captured, Mr. Molotov immediately proposed a toast to this victory of the Allied armies.

After a brief toast by Mr. Eden to Mr. Molotov as Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union and Chairman of the 1943 Moscow Conference, Mr. Stettinius also proposed a toast to Mr. Molotov. He said that he hoped that he would be able to carry on the fine work of his predecessor, Secretary Hull. He stated that Mr. Hull, who was now in a hospital but was recovering, had asked him to present his compliments to Mr. Molotov. He concluded by stating that he looked forward to the day when he, Mr. Molotov and Mr. Eden would have frequent meetings.

Mr. Molotov immediately rose and proposed a toast to the recovery of Secretary Hull. He requested Mr. Stettinius to convey to Mr. Hull the sympathy and best wishes of all those present at the luncheon. He then proposed a toast to the British Ambassador, who reciprocated by toasting the “Moscow Commission” and its continued cooperation. This was followed by toasts on the part of Mr. Stettinius to his Dumbarton Oaks colleagues (Messrs. Gromyko and Cadogan); to the health and success of bis ally, Mr. Harriman, by Mr. Molotov, and a toast to the important head of the Drafting Committee who asserted such control over the “Moscow Commission,” Mr. Vyshinski, by Mr. Harriman.

Mr. Justice Byrnes then proposed that the guests drink to the Great Armies of the Soviet Union and Ambassador Gromyko toasted Mr. Byrnes as a great American who had served in the three most important branches of the American Government.

Mr. Vyshinski suggested that Messrs. Strang and Winant, the co-workers on the European Advisory Commission be the subject of a toast.

Mr. Stettinius then raised his glass to Ambassador Gromyko, whom he described as an able and effective representative of the Soviet Union in Washington who had won the respect and admiration of the American people.

Mr. Molotov remarked that there had been enough toasts to the diplomats. He wished to raise his glass to Mr. Byrnes who held one of the most important positions in the United States Government. He said that it was hard for the average person to imagine just how important Mr. Byrnes was.

Mr. Eden then toasted the men who were fighting the war.

After a toast to the success of the present conference, Mr. Maisky was requested to make a few remarks. He raised his glass to the closest possible unity between the peoples, governments and chiefs of the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union and remarked that the future of mankind depended upon this unity.

During the course of the luncheon Mr. Molotov proposed a toast to the “Crimean Conference.” After a brief discussion it was suggested that the Conference should be so-called.

Mr. Eden inquired of Mr. Molotov as to what the Russians had in mind to discuss this afternoon.

Mr. Molotov replied that the Russian Delegation was prepared to discuss any question the United States or the United Kingdom Delegations so desired. This included those relating to the breaking up of Germany as well as political and economic matters relative to that country.

Mr. Eden stated that the general subject needed further study before any final decisions could be made.

Mr. Molotov remarked that in his view the Americans and British were considerably ahead of the Russians in their studies on this question.

Mr. Eden replied that although the British had studied the matter on a technical level, there had yet been no Cabinet discussions on the question. He stated that the President, the Prime Minister, and Marshal Stalin would in all probability be unable to come to any final decisions today on the subject of the treatment of Germany and suggested that the matter be the subject of a joint study on the part of the three countries.

Mr. Molotov favored this idea.

Mr. Eden continued with the suggestion that the Prime Minister, the President and Marshal Stalin discuss the treatment of Germany in general terms at today’s meeting, that they refer the question to the three Foreign Ministers for further study and that they instruct them to report back to the Big Three in two or three days with definite proposals.

Mr. Molotov indicated his approval of this proposal.

Mr. Stettinius stated in an aside remark to Mr. Molotov that the United States Government believed it very important that agreement be reached on certain economic considerations with respect to Germany.

Mr. Molotov indicated that the Soviet Government expected to receive reparations from Germany in kind and hoped that the United States would furnish the Soviet Union with long term credits.

Mr. Stettinius stated that his Government had studied this question and that he personally was ready to discuss it at any time with Mr. Molotov. This could be done here as well as later either in Moscow or in Washington.

Mr. Molotov indicated that now that the end of the war was in sight it was most important that agreement be reached on these economic questions.

Livadia Palace, USSR

| Present |

|---|

| President Roosevelt |

| Mr. Hopkins |

| Mr. Matthews |

| Mr. Bohlen |

Matthews in 1954: “I do not recall the subject but most such meetings were to inform the President of the results of our morning Foreign Ministers meeting and to prepare him for the afternoon agenda.”

Livadia Palace, USSR

| Present | ||

|---|---|---|

| United States | United Kingdom | Soviet Union |

| President Roosevelt | Prime Minister Churchill | Marshal Stalin |

| Secretary Stettinius | Foreign Secretary Eden | Foreign Commissar Molotov |

| Fleet Admiral Leahy | Sir Archibald Clark Kerr | |

| Mr. Hopkins | Sir Alexander Cadogan | Mr. Vyshinsky |

| Mr. Byrnes | Sir Edward Bridges | Mr. Maisky |

| Mr. Harriman | Mr. Dixon | Mr. Gusev |

| Mr. Matthews | Mr. Wilson | Mr. Gromyko |

| Mr. Bohlen | Major Birse | Mr. Pavlov |

Leningrad, February 5, 1945, 4 p.m.

Top secret

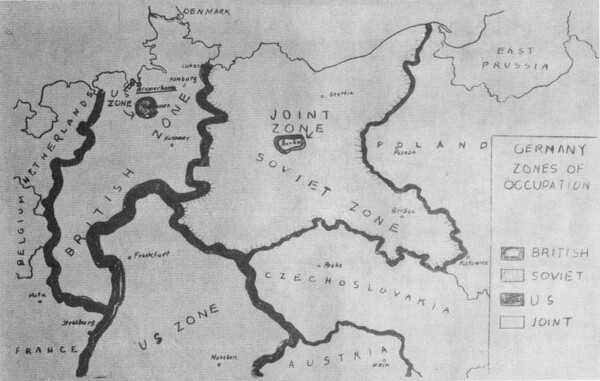

The President opened the meeting by stating that it was his understanding that political matters affecting Germany would be discussed today. He said that they would not cover the map of the world and discuss Dakar or Indochina, but confine themselves to the political aspects of the future treatment of Germany. He said that the first question was that of the zones of occupation, which he understood had been agreed upon in the European Advisory Commission. He said there was one question still open and that was the desire of France to have a zone of occupation and French participation in the control machinery for Germany. He emphasized that the question of zones did not relate to the permanent treatment of Germany.

The President then handed a map of the agreed tripartite zones to Marshal Stalin, pointing out that although these zones had been agreed upon in the European Advisory Commission they had not yet been signed by the three governments.

Marshal Stalin said that in the discussion of Germany he would like to include the following points:

The question of dismemberment of Germany. He said that at Tehran they had exchanged views on this subject and later at Moscow he had talked this subject over with the Prime Minister. From these informal exchanges of views he had gathered that all were in favor of dismemberment, but nothing had been decided as to the manner of dismemberment. He said he wished to know first as to whether the President or Prime Minister still adhered to the principle of dismemberment.

Marshal Stalin inquired whether the three governments proposed to set up a German government or not and if there was a definite decision on dismemberment whether or not the three governments would set up separate governments for the various parts of Germany.

Marshal Stalin inquired as to how the principle of unconditional surrender would operate in regard to Germany; for example, if Hitler should agree to surrender unconditionally, would we deal with his government?

Marshal Stalin said his last point dealt with the question of reparations.

The President replied that, as he understood it, the permanent treatment of Germany might grow out of the question of the zones of occupation, although the two were not directly connected.

Marshal Stalin replied that what he wished to find out here was whether or not it was the joint intention to dismember Germany or not. He said that at Tehran, when the question had been discussed, the President had proposed the division of Germany into five parts. The Prime Minister, after some hesitation, had suggested the division of Germany into two parts with a separation of Prussia from the southern part of Germany. He said that he had associated himself with the views of the President, but the discussion at Tehran had only been an exchange of views. He added that at Moscow with the Prime Minister they had discussed the possibility of dividing Germany into two parts with Prussia on the one hand and Bavaria and Austria on the other, with the Ruhr and Westphalia under international control. He said that he thought that this plan was feasible but that no decision had been taken since the President was not there. He inquired whether the time had not come to make a decision on the dismemberment of Germany.

The Prime Minister stated that the British Government agreed in principle to dismemberment but he felt that the actual method and a final decision as to the manner of dismemberment was too complicated to be done here in four or five days. He said it would require elaborate searchings by experienced statesmen on the historical, political, economic and sociological aspects of the problem and prolonged study by a subcommittee. He added that the informal talks at Tehran and Moscow had been very general in character and had not been intended to lay down any precise plan. In fact, he added, if he were asked to state here how Germany should be divided, he would not be in a position to answer, and for this reason he couldn’t commit himself to any definite plan for the dismemberment of Germany. The Prime Minister said, however, that personally he felt that the isolation of Prussia and the elimination of her might from Germany would remove the arch evil – the German war potential would be greatly diminished. He added that a south German state with perhaps a government in Vienna might indicate the line of great division of Germany. He said that we are agreed that Germany should lose certain territories conquered by the Red Army which would form part of the Polish settlement, but he added that the question of the Rhine valley and the industrial areas of the Ruhr and Saar capable of producing armaments had not yet been decided; should they go to one country, or should they be independent, or part of Germany, or should they come under the trusteeship of the world organization which would delegate certain large powers to see to it that these areas were not used to threaten the peace of the world. All this, the Prime Minister said, required careful study, and the British Government had not yet any fixed ideas on the subject. Furthermore, he said, no decision had been reached on the question as to whether Prussia after being isolated from the rest of Germany should be further divided internally. He said that we might set up machinery which would examine the best method of studying the question. Such a body could report to the three governments before any final decision is reached. He said we are well prepared for the immediate future, both as to thought and plans concerning the surrender of Germany. All that was required was a final agreement on zones of occupation and the question of a zone for France.

Marshal Stalin replied that it wasn’t clear to him as to the surrender. Suppose, for example, a German group had declared that they had overthrown Hitler and accepted unconditional surrender. Would the three governments then deal with such a group as with Badoglio in Italy?

The Prime Minister replied that in that case we would present the terms of surrender, but if Hitler or Himmler should offer to surrender unconditionally the answer was clear – we would not negotiate under any circumstances with any war criminals and then the war would go on. He added it was more probable they would be killed or in hiding, but another group of Germans might indicate their willingness to accept unconditional surrender. In such a case the three Allies would immediately consult together as to whether they could deal with this group, and if so terms of unconditional surrender would immediately be submitted; if not, war would continue and we would occupy the entire country under a military government.

Marshal Stalin inquired whether the three Allies should bring up dismemberment at the time of the presentation of the terms of unconditional surrender. In fact, he added, would it not be wise to add a clause to these terms saying that Germany would be dismembered, without going into any details?

The Prime Minister said he did not feel there was any need to discuss with any German any question about their future – that unconditional surrender gave us the right to determine the future of Germany which could perhaps best be done at the second stage after unconditional surrender. He said that we reserve under these terms all rights over the lives, property and activities of the Germans.

Marshal Stalin said that he did not think that the question of dismemberment was an additional question, but one of the most important.

The Prime Minister replied that it was extremely important, but that it was not necessary to discuss it with the Germans but only among ourselves.

Marshal Stalin replied that he agreed with this view but felt a decision should be made now.

The Prime Minister replied that there was not sufficient time, as it was a problem that required careful study.

The President then said that it seemed to him that they were both talking about the same thing, and what Marshal Stalin meant was should we not agree in principle here and now on the principle of dismemberment of Germany. He said personally, as stated by him at Tehran, that he was in favor of dismemberment of Germany. He recalled that forty years ago, when he had been in Germany, the concept of the Reich had not really been known then, and any community dealt with the provincial government. For example, if in Bavaria you dealt with the Bavarian government and if in Hesse-Darmstadt you dealt with that government. In the last twenty years, however, everything has become centralized in Berlin. He added that he still thought the division of Germany into five states or seven states was a good idea.

The Prime Minister interrupted to say “or less,” to which the President agreed.

The Prime Minister remarked that there was no need, in his opinion, to inform the Germans of our future policy – that they must surrender unconditionally and then await our decision. He said we are dealing with the fate of eighty million people and that required more than eighty minutes to consider. He said it might not be fully determined until a month or so after our troops occupy Germany.

The President said he thought the Prime Minister was talking about the question of dismemberment. In his view he said he thought it would be a great mistake to have any public discussion of the dismemberment of Germany as he would certainly receive as many plans as there had been German states in the past. He suggested that the Conference ask the three Foreign Ministers to submit a recommendation as to the best method for the study of plans to dismember Germany and to report within twenty-four hours.

The Prime Minister said the British Government was prepared to accept now the principle of dismemberment of Germany and to set up suitable machinery to determine the best method to carry this out, but he couldn’t agree to any specific method here.

Marshal Stalin said he wished to put a question in order to ascertain exactly what the intentions of the three governments are. He said events in Germany were moving toward catastrophe for the German people and that German defeats would increase in magnitude since the Allies of the Soviet Union intend to launch an important offensive very soon on the Western Front. In addition, he said that Germany was threatened with internal collapse because of the lack of bread and coal with the loss of Silesia and the potential destruction of the Ruhr. He said that such rapid developments made it imperative that the three governments not fall behind events but be ready to deal with the question when the German collapse occurred. He said he fully understood the Prime Minister’s difficulties in setting out a detailed plan, and he felt therefore that the President’s suggestion might be acceptable: namely, (1) agreement in principle that Germany should be dismembered; (2) to charge a commission of the Foreign Ministers to work out the details; and, (3) to add to the surrender terms a clause stating that Germany would be dismembered without giving any details. He said he thought this latter point was important as it would definitely inform the group in power who would accept surrender unconditionally, whether generals or others, that the intention of the Allies is to dismember Germany. This group by their signature would then bind the German people to this clause. He said he thought it was very risky to follow the plan of the Prime Minister and say nothing to the German people about dismemberment by the Allies. The advantage of saying it in advance would facilitate acceptance by the whole German people of what was in store for them.

The Prime Minister then read the text of Article 12 of the surrender terms agreed on by the European Advisory Commission, in which he pointed out that the Allied governments have full power and authority over the future of Germany.

The President said that he shared Marshal Stalin’s idea of the advisability of informing the German people at the time of surrender of what was in store for them.

The Prime Minister said that the psychological effect on the Germans might stiffen their resistance.

Both the President and Marshal Stalin said there was no question of making the decision public, and Marshal Stalin added that as far as he knew the surrender terms which Italy had accepted had not yet been made public.