The Pittsburgh Press (September 24, 1944)

Air army patrols reach British; gliders land more men in Holland

Arnhem battle called decisive struggle of west by Germans

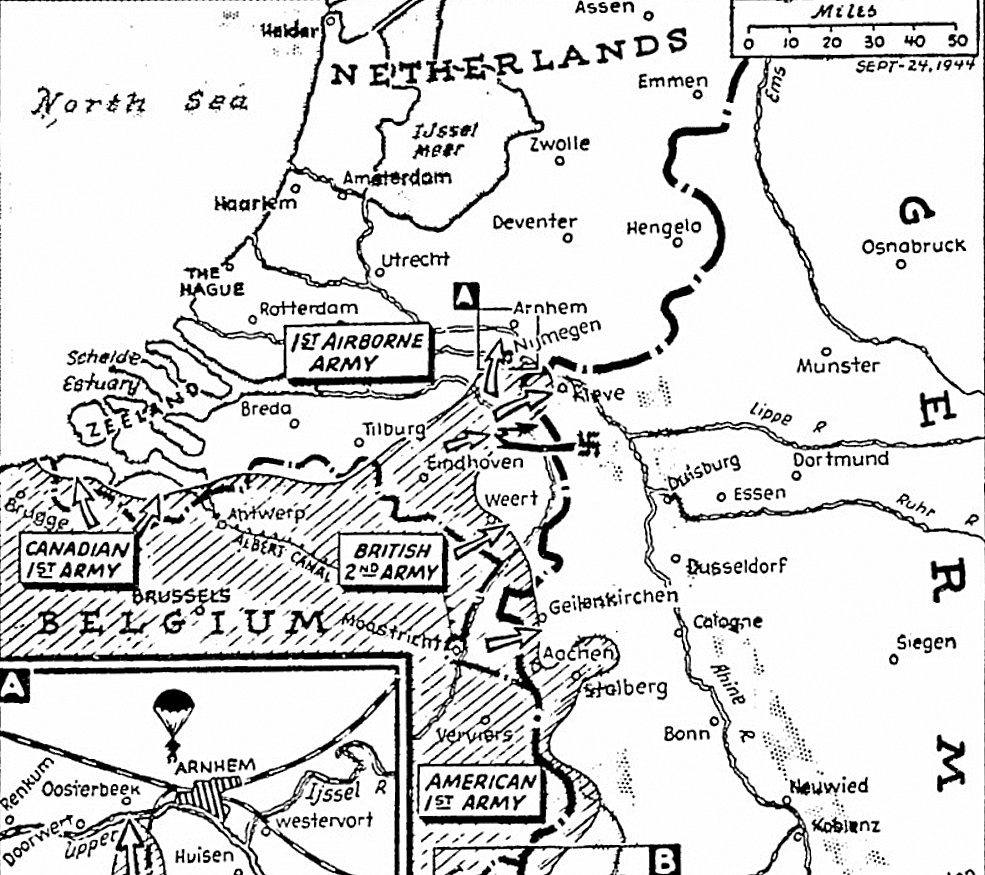

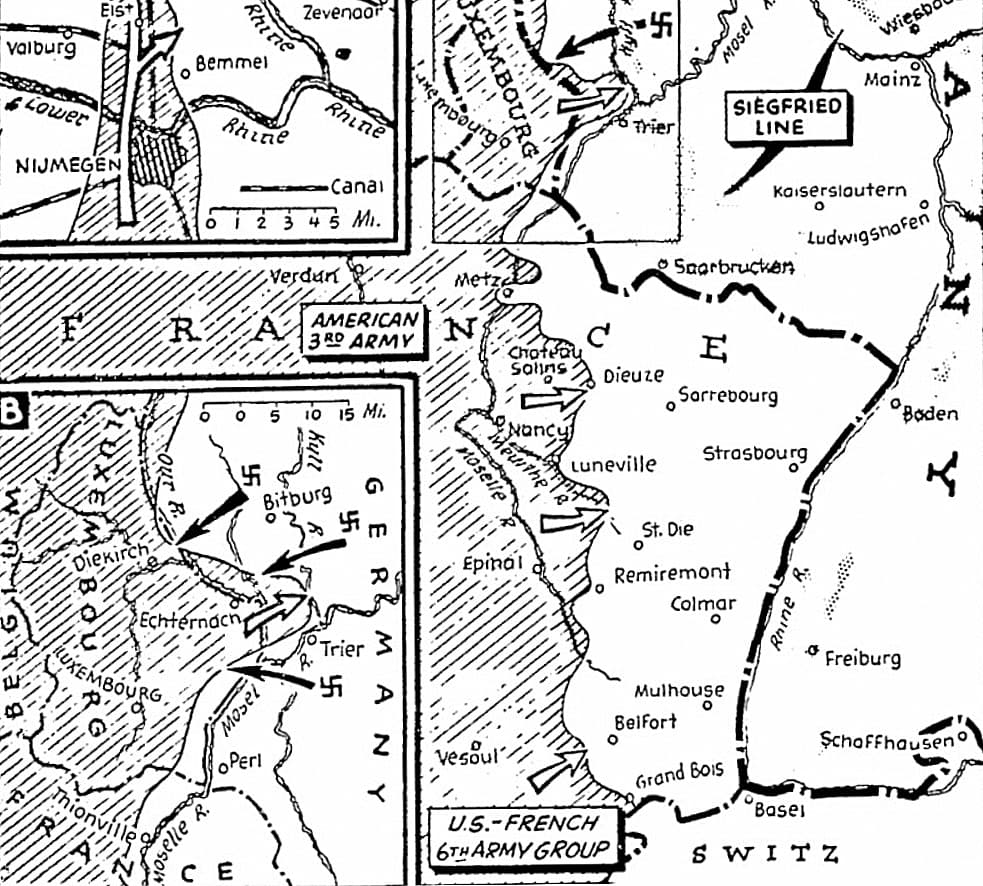

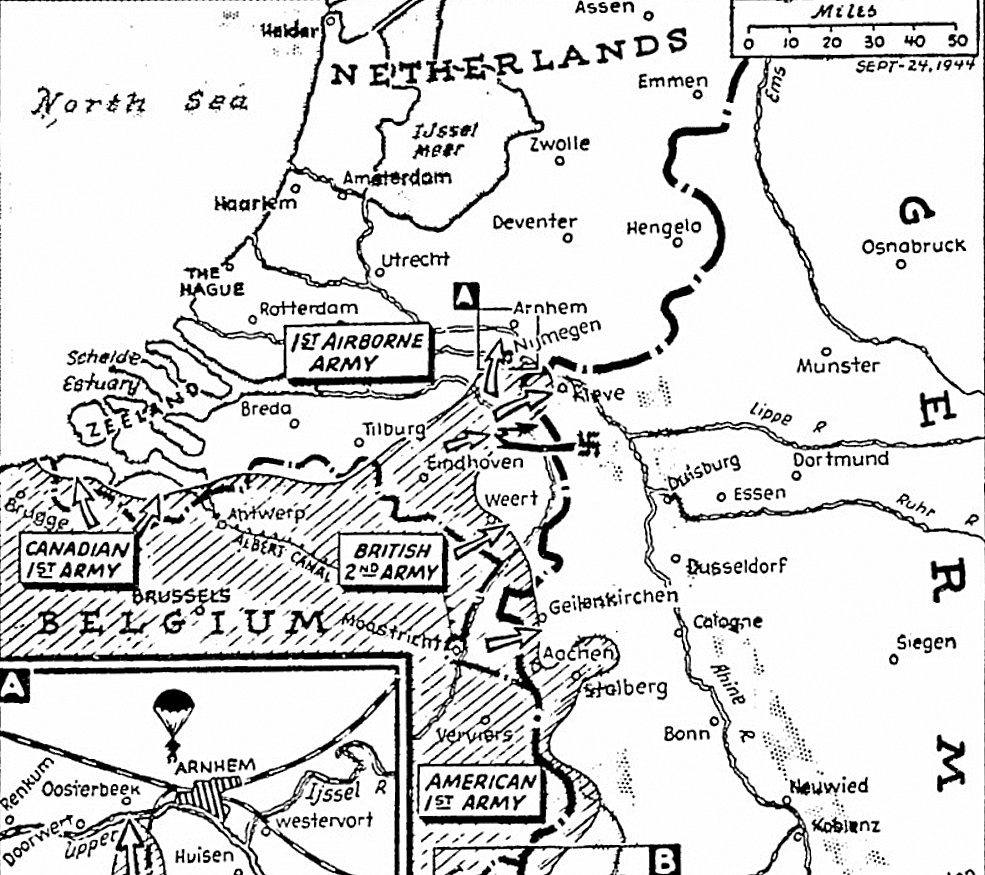

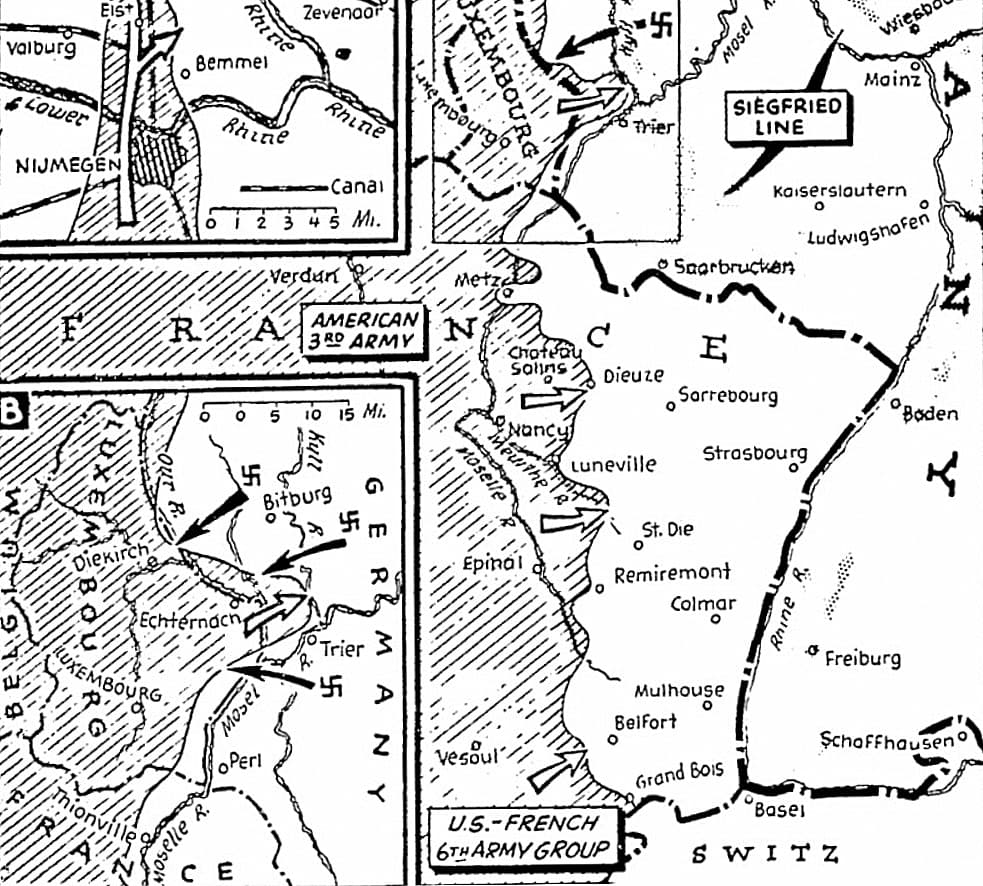

Still holding out in the Arnhem area on the north bank of the upper Rhine (inset map A), encircled airborne army patrols pushed to a junction with the British 2nd Army, which had driven to the south bank of the river and was reinforced by a new glider-borne force. A German tank force which thrust a wedge across the British corridor between Eindhoven and Nijmegen was repulsed. The U.S. 1st Army, while falling back across the Luxembourg border in the Diekirch area (inset map B), to the north captured the German industrial city of Stolberg. The U.S. 3rd Army smashed Nazi tank attacks in the area bounded by Château-Salins, Dieuze and Lunéville east of the Moselle River, and the Allied 6th Army Group drove against the Belfort Gap on the south.

SHAEF, London, England (UP) –

Patrols from the heroic Allied parachutist band cut off around Arnhem fought their way south across the upper branch of the Rhine Saturday and established contact with the British 2nd Army as a new sky army of thousands of Anglo-American troops swept down by glider to join the crucial battle.

Berlin called the struggle at Arnhem the decisive test of the war in the west and in an attempt to nip off the allied corridor Adolf Hitler sent 200 tanks lunging against its base 25 miles to the south. They were hurled back after temporarily cutting the vital Eindhoven–Nijmegen highway and driving a wedge in the salient.

Patrols pushing across the river from the airborne “island” established the “barest sort” of contact with the British rescue force, Allied headquarters said, but the fact that they were able to get across sent hopes soaring that a full junction would soon be made.

Furious battles raged along the 60-mile length of the Allied salient across Holland, but despite waves of counterattacks by crack SS and panzer units, the Allies were able to widen the corridor in at least two sectors.

Westward of Eindhoven, gains of four to five miles were made on a 12-mile front, while in the Nijmegen sector along the main branch of the Rhine, Lt. Gen. Sir Miles C. Dempsey’s 2nd Army infantry pushed eastward three miles, capturing Beek on the German border.

A sky train 170 miles long – extending unbroken from British bases to Holland landed the new sky army. Scores of DC-3 “Dakota” transport planes towed hundreds of big gliders bulging with troops and supplies. The reinforcements were landed successfully despite strong opposition from enemy ground defenses and also from the Luftwaffe, headquarters announced.

RAF and U.S. fighter planes in strength provided cover for the landings.

The reinforcements apparently were landed outside the pocket of airborne troops on the north bank of the river, since a special bulletin announced specifically that they descended in support of the 2nd Army’s drive.

Berlin said that reinforcements were landed between the two branches of the river but were not able to smash open the German “bolt” position north of Nijmegen on the southern branch or break through to the rescue of the parachutists around Arnhem.

Main bridge intact

Linking up with a smaller airborne force on the south bank of the river, the British found the main bridge to Arnhem still intact but it was unclear in late reports which side controlled the crossing.

The Arnhem area became the flaming local point of virtually the entire 250-mile front as sharp but inconclusive battles were fought along the West Wall inside Germany and battered enemy panzer forces withdraw to the Moselle sector after losing 317 tanks in 11 days.

The capture of Stolberg, five miles east of Aachen, was formally announced although strongpoints in the main city and industrial suburbs remained to be mopped up. With a population of 17,000, Stolberg is the largest German city yet taken.

Detour Nazi roadblock

Driving on four miles beyond Elst after detouring a German roadblock at that Dutch town, the British 2nd Army breasted withering fire from their flanks to reach the upper Rhine, a smaller branch of the main stream which had been forced at Nijmegen.

Against fanatical resistance from SS and other crack units, the British were now battling to effect a crossing and bring full relief to the paratroopers, mostly British units but including two groups of Polish reinforcements. Although they had been fighting against increasing odds for six days, the airborne troops’ commander messaged that morale was still high especially with rescue apparently so near.

Beyond the upper Rhine, which nearer the sea becomes the Lek, there is only the small tributary, Ijssel, separating the Allies from the rolling plains of Northwest Germany and the Ruhr, and the battle for the Reich was being fought along the water barriers rather than the already partly-turned West Wall.

Dispatches from Berlin via Zürich quoted a German War Office spokesman as calling the battle for Holland “decisive for the entire war in the west,” and said that Adolf Hitler had rushed suicide units of his own private guard to the Arnhem area.

Despite the short distance separating the 2nd Army from the main airborne force across the river, only several hundred yards, the situation of the parachutists was still described at headquarters as “touch and go.”

Meanwhile, a huge panzer force backed by crack infantry groups lashed out at the narrow British corridor through Holland in the area between Veghel and Uden, respectively, 12 and 15 miles north of Eindhoven. In a surging, bloody battle the enemy succeeded in smashing across the main Eindhoven–Nijmegen road, jugular vein for the units across the Rhine, but with the help of low-flying typhoon rocket planes British infantry succeeded in stemming the assault and clearing the road.

Batteries rain heavy fire

German batteries were still raining down heavy fire on the supply artery, however, and official dispatches said the German attack had achieved “a certain amount of success.”

A similar but smaller attack from the west, where some 70,000 to 100,000 Germans have been cut off by the British drive, was smashed and the British went on to widen their corridor to 18 miles in the Eindhoven area on a 12-mile front.

United Press writer Ronald Clark reported that the whole of Central Holland had become a series of separate battlefields, with the Germans fighting fiercely from small, bypassed villages, utilizing whatever local forces were still intact.

Rain and low clouds prevented the air forces from joining in the main Arnhem battle early Saturday but later in the day huge forces of fighters and bombers were reported heading for Holland.

First Army breaks attack

On the 1st Army front, U.S. artillery drove back a counterattack northwest of Geilenkirchen where the Yanks had driven across the frontier from Dutch Maastricht, and another counterblow was beaten back in the Büsbach area southeast of Stolberg, costing the Germans 40 percent of the forces involved.

Heavy enemy resistance was encountered in the Hürtgen Forest in the same general area, where the Germans had thrown up an elaborate system of pillboxes and roadblocks behind the breached main defenses of the Siegfried Line.

The Americans were forced to give ground for the second straight day east of Diekirch, which is in Luxembourg, where dispatches indicated Friday the Yanks had been thrown back from German soil.

A German communiqué asserted that the Americans had been cleared from their own river bridgehead at the Luxembourg frontier in the Echternach area, with heavy casualties inflicted on the U.S. 5th Armored Division.

Front dispatches said the Germans lost 60 more tanks in the Moselle River in 24 hours in contrast to “considerably smaller” U.S. losses and the enemy was reported withdrawing from the Lunéville–Château-Salins area to a new defense line behind the Seille River.

Taking advantage of rain and mud which hampered American efforts to disrupt the defense preparations, the Germans were reported digging in strongly behind the 40-foot-wide Seille, which parallels the Moselle south of Metz and joins it above the citadel.

The Germans were apparently still determined to hold Metz at all costs and were strengthening its perimeter forts.

Sixth consolidating gains

Units of the 6th Army Group which had thrown a number of bridgeheads across the Moselle farther south were consolidating their gains despite counterattacks which at one point numbered nine in 24 hours. Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch’s 7th Army from the south was working closely with the U.S. 3rd Army in these operations.

On the Dutch southwest coast, 1st Canadian Army troops bottled up the German remnants on the south side of the Schelde estuary between the sea and the Leopold Canal while Polish troops on their right cleared out the Axel-Hulst nearer Antwerp. Northeast of the port, a Canadian unit fought its way across a canal just northeast of the city in a drive to clean out the troublesome enemy garrison in Fort Mexem.

It was announced that the Canadians captured more than 9,000 prisoners at Boulogne.

Arnhem battle crucial, Washington believes

Washington (UP) –

Military observers, confident of a final Allied victory in the great battle now raging along the Rhine for the Arnhem bridgehead, said tonight that this campaign may be the most decisive of the war.

Whatever chance the Allies have of ending the war before next spring may be lost, they said, if the Germans succeed in holding off our heavy armor long enough to annihilate the airborne army now hanging on to the Rhine positions.

If the Allies break through the enemy positions in force, they would have a chance to end the war before winter, the observers said. This breach would mean that the West Wall had been outflanked, the barrier of the Rhine River bridges and the Ruhr road to Berlin thrown open.

The battle is now in its most delicate stage for the Allies, seesawing and swirling with such rapidity that it is impossible to get a clear picture of it here. However, some decision should become apparent within the next week, it was believed.