Editorial: The Republican platform

The two-party system under which American democracy operates requires compromise. Both the Republican and Democratic parties are in fact coalitions to many minor parties. If they are to avoid being pulverized into fractions, their right wings and their left wings must somehow get together. The extreme position is not practicable and cannot be expected. But this does not mean that a party platform ought to be a mere bundle of promises to catch votes. There are certain broad principles and major issues on which the electorate is entitled to expect clear and unequivocal declarations, and that is particularly true in times like these. It is in the light of its positions on such principles and issues that a platform should be judged.

Foreign policy

The Republican Party pledges (1) “prosecution of the war to total victory,” (2) “full cooperation with the United Nations,” (3) “Pan-American solidarity,” (4) “maintenance of post-war military forces and establishments of ample strength” (but without mention of a system of compulsory military service for this purpose), (5) restoration to “sovereignty and self-government” of the victims of aggression, (6) treaties for our enemies “based on justice and security,” (7) no American membership in “a world state,” but instead (8) “responsible participation by the United States in post-war cooperative organization among sovereign nations” which “should develop effective cooperative means to direct peace forces to prevent or repel military aggression.” To this, the party adds a demand that all treaties and commitments be ratified under the present constitutional requirement for a two-thirds vote of the Senate.

There are two points here which we find disappointing. We are sorry that the Republican Party did not take this excellent opportunity to propose a constitutional amendment for the ratification of treaties by plain majority vote, so as to put an end to the evils of minority obstruction which have bedeviled American foreign policy for a generation. And we are sorry that the party lacked either the foresight or the courage to propose a democratic system of post-wat compulsory military service; for without the aid of such a system, it is simply not going to be possible for the United States to maintain military forces “of ample strength” for its post-war responsibilities. But considering the program as a whole it seems clear that the action proposed is about what the American people expect and will approve. Certainly, this country is not ready now (nor is any other major power) either for membership in a “world state” or for an “international police force” in the sense of a military establishment independent of existing sovereign governments. There is no issue here between Republicans and Democrats. President Roosevelt has already taken the same position, regarding the fundamentals of organizing peace, which the Republicans now take.

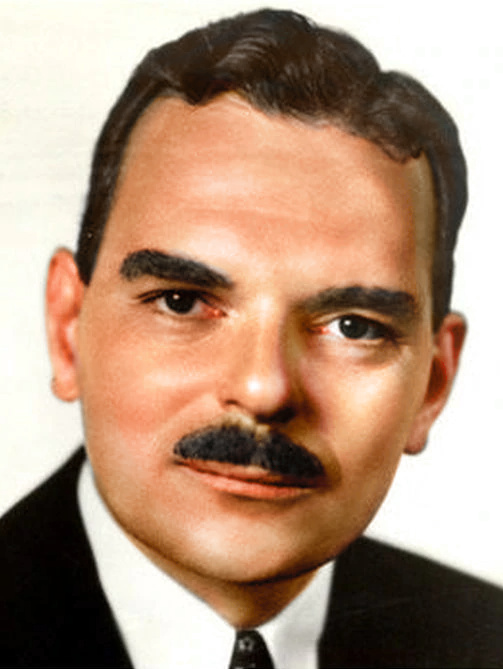

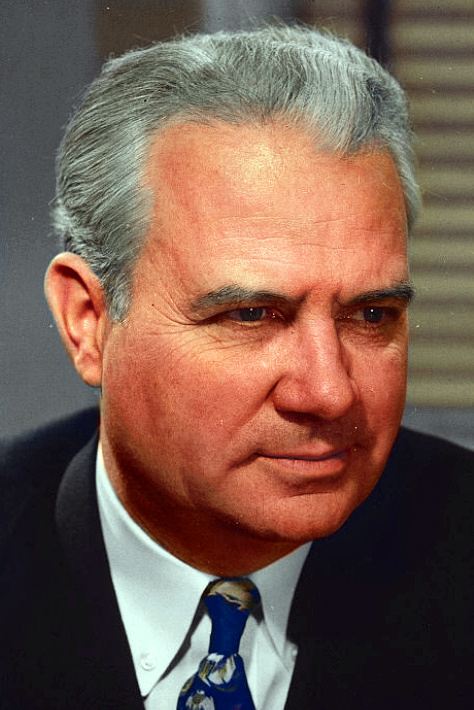

It is true that the formula in which the Republican Party has stated its own method of organized peace – “responsible participation in post-war cooperative organization among sovereign nations to… develop effective means to direct peace forces” – is a jumble of words into which it is impossible to read any concrete meaning. It is also true that there are holes in this pledge as wide as several barn doors, through which Mr. Dewey, if elected, could make an easy exit if he chose to make an exit. But there are three things to be said here. First, it is difficult for a minority party, out of power and lacking a benefit of conferences with the governments of other nations, to write a very concrete plan for so large and complex a problem as the organization of world peace. Second, no platform pledge, in any case, can be made so tight as to leave no loophole if the party does not really mean to keep its word. And third, the real meaning and degree of integrity of this particular pledge can only be gauged by the interpretation and the emphasis which Mr. Dewey gives it.

By this, we do not merely mean what Mr. Dewey says when he goes to Chicago to accept the nomination. We mean what Mr. Dewey continues to say, in speech after speech, as the campaign develops. For it is clear that there are sections of the country in which strongly isolationist Republican newspapers and Republican Senators with monumentally isolationist records will attempt to whittle away the platform pledge until it means nothing. They will dwell long and lovingly on such words as “sovereignty,” “no world state” and “looking out for American interests and resources.” And they will

Mr. Dewey will have no alternative but go into these newspapers and Senators on their home ground, if he wishes either to give real meaning to his party’s pledge or to obtain a mandate from the electorate for position action in the event of his election.

Domestic policy

On the domestic side, the best sections of the platform are those which deal with the question of post-war reconversion and which put their emphasis on the necessity of encouraging a revival of the private enterprise system which has always provided the great bulk of employment in this country and for which government-sponsored projects can never provide a satisfactory substitute.

For the rest it must be said that the domestic platform consists largely of special inducements to special groups, plus a liberal borrowing of planks from the New Deal itself. Prominent among the former group, and presumably designed to win the support of American farmers and some American industrialists, is a proposal which would seem to jeopardize the whole structure of Secretary Hull’s tariff agreements, since it implies that in future such agreements should be restricted only to those directly “approved by Congress” – which would mean, as experience has proved, no agreements at all. Among the issues borrowed from the New Deal are practically all of the major legislative enactments of the last ten years, plus a plentiful sprinkling of new subsidies and public works. At the same time, though the government’s responsibilities and activities would be larger than ever, if this program were adopted in its entirety, expenditures are to be cut, taxes reduced as soon as the war ends and the “sprawling, overlapping bureaucracy” somehow diminished.

All this is disappointing because, instead of sharpening differences between present administration policies and proposed Republican policies and proposed Republican policies, its net effect is to blur them. the section on labor is an outstanding illustration of this. The administration’s labor policy is extremely vulnerable and the Republican platform is thoroughly justified in criticizing the conflicting jurisdictions of federal labor agencies. But the Republicans show no courage whatever in dealing with basic issues of policy. There is no demand for union responsibility, for example, commensurate with union privileges. So far from any demand for amendment of the Wagner Act, the platform “accepts the purposes” of that act by name, together with the Wage and Hour Act. It appears that it is the “perversion of the Wagner Act by the New Deal” that is the evil. Rather than any unbalance in the act itself. Going further, the platform demands that the Secretary of Labor “should be a representative of labor” – that is, a union leader, presumably named by the unions themselves. On the same pressure theory of government, the Secretary of Agriculture should be named by the farm organizations, and the Secretary of Commerce should be a representative of business named by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce or the National Association of Manufacturers.

But in the scramble for the “labor vote” the worst declaration of all is this: “We condemn the freezing of wage rates at arbitrary levels and the binding of men to their jobs as destructive to the advancement of a free people.” This is written as if there were no such thing as a total war going on, no such thing as an inflation danger, and no such thing as a price-control policy. To remove the wage controls would blow off the price ceilings. The greatest danger to the anti-inflation program at this time is that the administration may be tempted for political reasons this fall to break the Little Steel formula. Instead of standing firmly against such a step, the Republicans in this declaration actually put pressure or the President to take it. What will the Republican Party itself have left to say if he does it?

We have become accustomed to national platforms intended as a catch-all for votes. The present one is unfortunately typical of these. But as the nominee of his party, Mr. Dewey will still have the opportunity to improve the platform by a sensible interpretation of ambiguous pronouncements and by courageous supplement of his own.