Marines at Tarawa buried Japs, prayed

…

The Pittsburgh Press (May 22, 1944)

By Ernie Pyle

A B-26 base, England –

“My crew” of two officers and three enlisted men have been flying together as a team in their B-26 bomber since before leaving America more than a year ago.

Every one of them is now far beyond his allotted number of combat missions.

Every one of them is perfectly willing to go through another complete tour of missions if he can just be home for a month. I believe the same thing is true of almost everybody, at this station. And it’s a new experience for me, because most of the combat men I’ve been with before wanted to feel finished forever when they went home.

Every one of “my crew” has the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal, with clusters. They have had flak through their plane numerous times, but none of them has ever been hit. They expect it to be rough when the invasion starts, but they’re anxious to get it over with.

In the past they have usually flown one mission a day over France, with occasionally two as the tempo of spring bombings increased. But during the invasion they will probably be flying three and sometimes four missions a day.

They will be in the air before daylight and they will come home from their last mission after dark. They will go for days and maybe weeks in a frenzied routine, eating hurriedly between missions, snatching a few hours of weary sleep at night, and being up and at it again hours before daylight to shuttle back and forth across the Channel. They and thousands of others like them.

Fighting purely an air war – as this one here has been up to now – is in some ways so routine that it is like running a big business.

Usually a B-26 crewman “works” only about two hours a day. He returns to a life that is pretty close to a normal one. There is no ground war to confuse him with its horror. His war is highly technical, highly organized, and in a way somewhat academic.

Because of this, it is easy to get bored. An air crewman has lots of spare time on his hands. Neither the officers or the enlisted fliers have any duties whatever other than flying.

When not flying they either loaf around their own huts, writing letters or playing poker or just sitting in front of the fire talking, or else they take leave for a few hours and go to the nearby villages. They can go to dances or sit in the local pubs and talk.

And every two weeks they get two days’ leave. That again is something new to us who have been in the Mediterranean. Down there fliers do get leave to go to rest camps, and even to town once in a while if there is a town, but there’s nothing regular or automatic about it. These boys up here get their two days’ leave twice a month just like clockwork. They can do anything they want with it.

Most of them go to London. Others go to nearby cities where they have made acquaintances. They go to dances at nightclubs and shows. They paint the town and blow off steam as any active man who lives dangerously must do now and then. They make friends among the British people, and they look up those same friends on the next trip to town.

They do a thousand and one things on their leave, and it does them good. Also, it gradually creates an understanding between the two people that the other is all right in his own peculiar way.

After a certain number of missions, a crew is usually given two weeks’ leave. Most of them spend it traveling. Our fliers often tour Scotland on these leaves. It’s amazing the number of men who have been to Edinburgh and who love the place. They have visited Wales and North Ireland and the rugger southwestern coast, and they know the Midlands and the little towns of England.

These two-week leaves don’t substitute in the fliers’ mind for a trip back to America. That’s all they live for. That’s what they talk about most of the time.

A goal is what anyone overseas needs – a definite time limit to shoot for. Naturally it isn’t possible right at this moment to send many people home, and the fliers appreciate and accept that fact. But once the invasion is made and the first period of furious intensity has passed, our veteran fliers hope to start going home in greater numbers.

A LIFE editor at Aitape reports on, among other things, a Jap prisoner ‘fished’ from dugout

By Noel F. Busch

…

Before stampeding to Dewey, the delegates should consider the claims of the Midwest

As a magazine, LIFE is neither Democrat nor Republican. If and when this magazine comes out for a candidate in the 1944 campaign, it will do so from a nonpartisan base. Thus, in giving some advice to the Republican Party, which we now propose to do, we are not adopting that party, or asking it to adopt us. We are giving it the kind of advice which any outside has the right to offer to any party whose affairs are, after all affected with a public interest.

The delegates to the Republican National Convention seem at the present moment to be hellbent on nominating Governor Dewey as fast as possible and then hellbending home. This may turn out to be a good thing for them to do. But our advice is: think it over. A case can be made that the best thing the Republicans can do is nominate a Midwesterner. And not only the best thing for the Republicans, but – more to the point – the best thing for the country in case they win the election.

The Republican renascence

The average delegate entraining for Chicago next month knows there is a widespread reaction against Washington bureaucracy, against OPA, against 12 too-exciting years of personal and theatrical government. he figures it’s a Republican year, so what the hell. It is true that this may be an anti-Roosevelt year. But if it is also a Republican year, what made it so? What and who revived the Republican Party? How does it happen that the anti-Roosevelt sentiment, instead of skulking through the streets, has a respectable vehicle?

The mainspring of the Republican renascence is the Midwest. Here, in the birthplace of the Republican Party, the land of corn, wheat and Lincoln, the Republican renascence got its start. Since 1938, the Midwest has been returning Republicans to Congress in an ever-widening stream. It gave Willkie 68 of his 82 electoral votes in 1940. Even those Midwestern states that went for Roosevelt that year went Republican in their state governments. To be sure, other sections did their share to keep the party together, notable New England. Nevertheless, the spearhead of Roosevelt’s Congressional opposition is 22 senators from the Midwest. The Midwest is the one section which can be counted on to go Republican this year.

For that very reason, many leading Republican politicians feel that it is unnecessary to take the Midwest’s mood into account. They concentrate their calculations on the problematical East and West. Hence: “Dewey and Warren.” Although the Midwest would support this ticket, it would rather have some recognition for its years of loyalty and hard work. But quite apart from that, there are serious national reasons why a Midwesterner, if the country goes Republican, should take the responsibility that goes with the victory the Midwest will have earned.

Whoever is President during the next four years will not have an easy time. While he is trying to conclude the peace treaties with one hand, the other will have to deal with a turmoil of demobilization. For a while the economic pie will be smaller; inevitably there will be renewed bitterness over who gets what. In that bitterness, group and sectional rancors will come boiling to the top.

Of sectional prejudice, the Midwest has perhaps a little more than its share. At its worst, it is suspicious of foreigners, of the East, of big cities (including its own), of Wall Street and of Big Business. The only thing the Midwest completely trusts is itself. The Midwest is just like the rest of America, only more so.

How can the Midwest be kept at its best during the next four dangerous years, instead of at its worst? By giving it responsibility, which is the surest antidote to prejudice. With 22 Senators, the Midwest is bound to exercise a great deal of power, of it does not enjoy responsibility commensurate with this power, it may become more self-sufficient, self-regarding and exclusively regional than ever.

Republican foreign policy

Among the serious consequences of such a withdrawal would be its effect on U.S. foreign policy. This would be the first target of the Midwest’s suspicions.

A lot has happened in the last few weeks to change the Republican position on foreign policy. Soon after Willkie’s withdrawal from the race, Governor Dewey came out for Secretary Hull, Governor Bricker came out for post-war credits abroad, and both came out for a joint peacekeeping deal with Britain, Russia and China. Meanwhile Senator Taft has written a blueprint for a new League of Nations and, of course, ex-Governor Stassen went on record with his famous seven-point program way back in January 1943. Throw in progressives like Senators Ball and Burton and throw out the Illinois crowd (who though powerful are not candidates) and you emerge with a wholly new Republican orientation: its leaders, even without Willkie, are all on record against anything that could remotely be termed “isolation.”

Now, the Midwest is the old home of isolation. The Midwest today is not against America’s participating in world affairs; but it is still very skeptical about any program of participation that has been offered to it to date. It is still isolationist in a relative sense; it is capable of supporting an active foreign policy, but only after its doubts about the motivation of that policy are completely removed. And the doubts of the Midwest spring from its prejudices – its suspicions of all foreigners and their supposed influence on the East.

A vocal handful of diehard Willkieites may say, “The Midwest is hopeless. No appeasement!” That is tantamount to saying that on foreign policy, the Republican Party without Willkie has no case.

But the Republicans have a foreign policy case. Their case is that internationalism will be not so much an issue as a fact of post-war life. Given this fact, U.S. foreign policy should be one of enlightened and responsible selfishness. Their case is not that Roosevelt is too inclined to make commitments, but that he cannot make his commitments stick. Congress will probably be Republican and certainly anti-Roosevelt; therefore, only a Republican President can make any foreign policy responsible and effective.

The Republican case is that when a Republican President sits down with Stalin, Churchill, Chiang Kai-shek and whoever else, the meeting will get somewhere; for Stalin et al. will know that the presidential signature on a treaty will not be written in vanishing ink.

Keep it clean

But if this is a good case for a Republican President, why is it not an even better case for a Midwestern Republican President?

If a Republican foreign policy were administered by a Midwesterner, its selfishness would never be open to doubt. For the Midwest trusts its own – especially those whom it has elected to office. With both the selfishness and the responsibility of our foreign policy assured, the debate could then be conducted on one level only: is it enlightened? This debate will go on forever. Our problem will be not to end it, but to keep it on this high plane.

The best way to keep it on this high plane is to stage it at the corner of Main and Elm. To the Midwestern eye, America is merely an extension of these two streets, and maybe the Midwest is right. In any case, they are long, straight streets, and they can lead to all parts of the world.

By naming a Midwestern candidate, the Republicans will assure the country that the great post-war debate will not degenerate into a sectional brawl. Yet to name a Midwesterner would not turn the Republicans into a sectional party, or an isolationist party, or otherwise narrow its base. There are at least four candidates – Bricker, Burton, Stassen, Taft – who are not only representative Midwesterners, but also men with a national viewpoint, and an expressed realization of America’s need to participate in world affairs.

The political case for Dewey is a strong one: his state is doubtful, while the Midwest is not, and any party has to figure things very closely when it is up against The Champ. But the delegates to Chicago will perform a patriotic service if they delay the stampede at least long enough for the Midwest’s case to be heard.

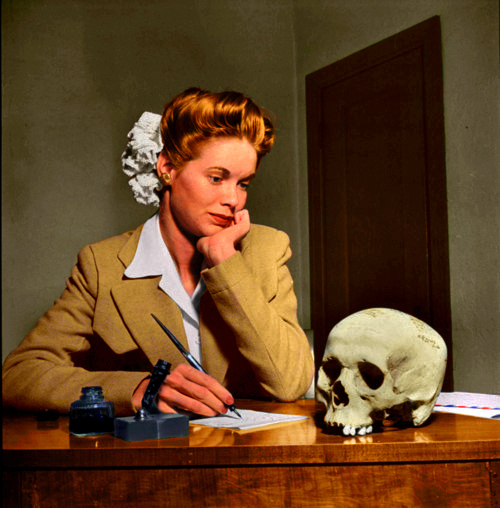

Arizona war worker writes her Navy boyfriend a thank-you note for the Jap skull he sent her.

When he said goodbye two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Arizona, a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap.

Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends, and inscribed: “This is a good Jap – a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach.” Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The armed forces disapprove strongly of this sort of thing.

An American student was sole eyewitness at killing of Reinhard Heydrich

By Harold Kirkpatrick as told to Gerald Frank and James D. Horan

…

A distinguished historian recalls the past of two recently captured Pacific groups

By Samuel Eliot Morison

…

U.S. Navy Department (May 23, 1944)

For Immediate Release

May 23, 1944

Army, Navy, and Marine shore‑based aircraft dropped 230 tons of bombs on Wotje Atoll on May 21 (West Longitude Date). Liberator and Mitchell bombers of the 7th Army Air Force, Dauntless dive bombers and Corsair fighters of the 4th Marine Aircraft Wing, and Navy Hellcat fighters flew 207 sorties in the coordinated attack. Specific targets were strafed by Mitchell bombers and Corsair fighters. Antiaircraft fire was meager. All of our planes returned, although ten suffered minor damage.

Corsair fighters of the 4th Marine Aircraft Wing bombed Mille Atoll on May 21.

The Brooklyn Eagle (May 23, 1944)

U.S. battleships shell enemy in support of drive

By Reynolds Packard

…

‘Largest air fleet ever assembled’ reported bombing targets in Reich

…