Editorial: War information – sometimes

…

His backers say Willkie’s boom ‘collapsed,’ plan draft

By Thomas L. Stokes, Scripps-Howard staff writer

…

U.S., British and Canadian fliers help convoys below Iceland

By James McGlincy, United Press staff writer

…

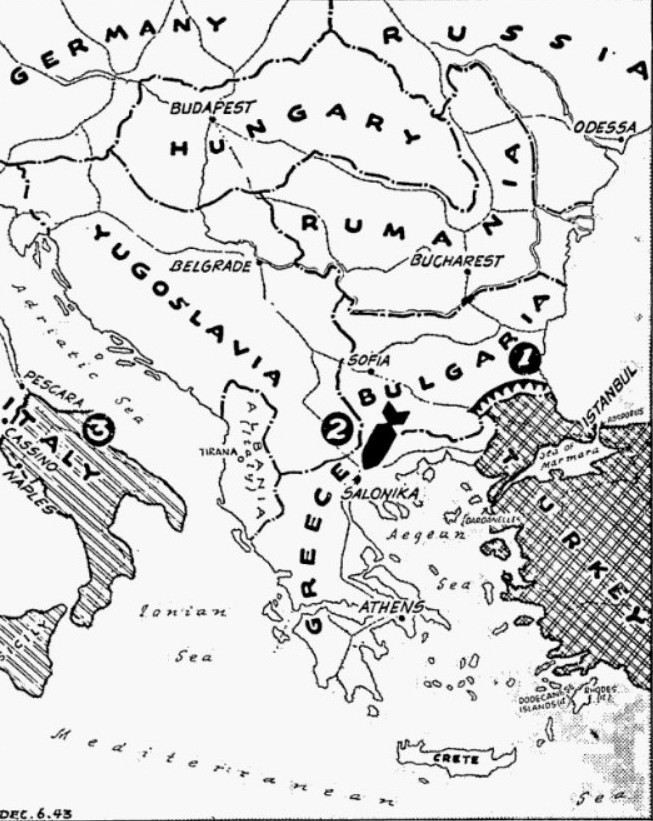

Invasion of the Balkans was hinted today as one of the possible Allied blows mapped at the Tehran Conference. Berlin, evidently fearing that Turkey might be drawn into the war, was reported massing troops on the Bulgarian-Turkish border (1). Allied planes bombed Salonika, Greece (2). Meanwhile, in Italy (3) Yanks seized three more heights dominating the main road to Rome.

Pacific conference site converted into spy-proof, enemy-proof and reporter-proof perimeter

By Richard Mowrer

Cairo, Egypt –

One bright morning, in the second week of November, an indignant British major stomped into the office of the manager of the swank Mena House hotel, famous tourist establishment within an easy walk or camel ride of the Sphinx and the Pyramids and, since the war, the favorite residence of GHQ officers.

“What’s the meaning of this?” the irate major demanded, thrusting a piece of paper at the manager.

“This,” was a short notice of request to the client to leave Mena House and find residence elsewhere.

Sixth to protest

The hotel manager barely bothered to look up from his desk.

Glancing at the crowns on the major’s shoulder, he said:

I am very sorry, sir. You are the sixth client to have protested this morning and four of them were brigadiers. Sorry.

This, according to the story, was the first intimation of the impending Mena conference. The following day, Cairo newspapers carried an item stating that Mena House was being closed down for repairs and cleaning, probably preparatory to the arrival of important personages.

Things move fast

At Mena, things began to move fast. Twenty British and American officers, assisted by 200-300 enlisted men, started the job of converting Mena House and 43 private villas near there into a strongly-protected, spy-proof, enemy-proof, reporter-proof perimeter.

Residents of Mena House having been dismissed, all the hotel staff was fired. Each servant was checked by security officers and in most cases rehired. The inside of Mena House, meanwhile, was revamped, bedrooms on the first, second and third floors being converted into 80 officers, while halls and salons on the ground floor became conference rooms.

Delegates were to live outside the hotel in villas.

One gets 1,500 pounds

Acquiring the needed villas was not easy. Owners were offered monetary compensation in return for immediate evacuation for a one-month period, from Nov. 18 to Dec. 18. One villa owner declared that he was damned if he would move out of his own home for anybody. The officers mentioned compensation. The obdurate subject remarked jokingly, “make it 1,500 pounds, Egyptian.”

One of the officers pulled out a checkbook and wrote out a check for that sum. They got the villa.

On the other hand, some villa owners were most gracious about the business. An Egyptian woman, when told the reason why her house was wanted, refused any compensation, declaring she was glad thus to contribute to the cause of the United Nations.

In the area enclosed by the Mena conference perimeter lived Egyptian peasants. There were checked by security officers and permitted to remain.

Trenches dug

Not since the gloomy days of El Alamein, when the enemy was still heading for Alexandria and Cairo felt directly threatened, has there been so much barbed wire in Mena and the Pyramids area. Each villa was surrounded by barbed-wire entanglements. Air-raid shelters and slit trenches were dug.

Mena House swimming pool was fitted with two pumps and kept filled with water in case of fire. Numerous anti-aircraft batteries were set up; searchlight emplacements were prepared. There were several British Army camps within the perimeter. An American camp to house 1,080 American drivers, MPs, guards and other personnel was also built.

On Sunday night, Nov. 21, after the arrival of Mme. Chiang Kai-shek and the Generalissimo and before the arrival of President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, the perimeter’s searchlights swept the skies for half an hour while a place droned overhead. Everything was all set for the conference.

‘A grand looking outfit,’ Roosevelt tells Elliott

By Robert Vermillion, United Press staff writer

Allied air base, North Africa – (Dec. 4, delayed)

The man in the gray fedora rode slowly in a jeep past a mile-long array of soldiers, swung back and stopped in front of the colonel commanding.

The colonel stepped forward two paces and saluted. The man in the fedora returned the salute and stuck out his hand.

The President of the United States said to his son:

It’s a grand looking outfit; you’ve done a good job, Elliott.

“Thank you, sir,” the colonel replied.

Marshall in party

The presidential review of Col. Elliott Roosevelt’s photo reconnaissance wing took place on a North African airfield where Mr. Roosevelt and his party, including Gens. George C. Marshall and Dwight d. Eisenhower, paused on their way east for the conferences at Cairo and Tehran with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Marshal Joseph Stalin.

The President’s plane descended at a specially-guarded airdrome near his son’s base early in the morning. The review was delayed for security reasons and it was sunset when the jeep rolled onto the field and started down the double line of Americans, British and French. The long shadows flickered across the President’s jeep as it moved down the field.

‘Chees, it’s the President’

Pvt. James M. Bettersby, 19, of Kewanee, Illinois, who was in the front rank, described the amazement of the troops this way:

We all figured it was somebody big but I was looking straight ahead. Then up the line I heard another guy kind of whisper “Chees, it’s the President.” I felt like I had stepped on a live wire.

Then he drove by. You couldn’t miss him, sitting up there in front with that same old hat turned up at the brim and that black Navy cape. I swear he must have looked every man in the eye. It left me kind of limp.

Arnold trails

Lt. Col. Charles Marburg of Baltimore said Gen. Eisenhower and Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz sat in the back seat of the President’s jeep and Gen. H. H. Arnold trailed – a four-star general in a jeep with a brigadier general’s single star.

Maj. Philip Kennedy of San Rafael, California, said of the President:

He didn’t move a muscle of his face. His white hair moved in the breeze. I never felt so darned proud in all my life.

Pittsburgher in line

Cpl. Thomas Mackey, 25, of Vallejo, California, said all the men turned a little to watch the President go by. Pvt. Thomas Coll of Pittsburgh vowed he saw the President’s Scottie, Fala, on the front seat of a command car. Sgt. Robert Lowry, 24, of Cincinnati, Ohio, said the presence of Mr. Roosevelt in Africa loosened a mass of rumors.

2nd Lt. E. C. Curry of Joplin, Missouri, told of a South African flight lieutenant of Norwegian birth who got so excited telling about how the MPs stopped him and the President shook hands with him on the road to the field that he lapsed into excited Norwegian. The pilot said he was so excited he didn’t see the President’s bestarred companions.

By Ernie Pyle

Allied HQ, Algiers, Algeria – (Dec. 6, by wireless)

We flew two nights and three days and then we were here. It was my fourth flight across the Atlantic. I’ve got to the point where I imagine I can see tracks in the sky from my previous crossings.

My good luck held out for the whole trip and we never had a single air bump worth mentioning in 8,000 miles. We came in Army planes all the way – some of them big, comfortable stratoliners, some of them workhorse planes with tin bucket seats. Only three of us who left the original airports in the States came clear through together.

At various times during our trip, we had as fellow passengers an American general, a Chinese major, some French fliers, a Yugoslavian and a half-dozen American girls going to far-scattered places to work as government secretaries.

Everybody thought the girls were a show troupe, and at one stop the commanding colonel was going to take them off the plane and make them give a show for his troops.

Initiated by Chinese major

The girls were good travelers and didn’t seem to mind the discomforts of flying all day and all night without rest. As soon as the plane would get off the ground, they would take off their shoes. On one of the big planes, the pilots took them up one by one and gave them the thrill of sitting in the pilot’s seat.

When we crossed the equator, the Chinese major, who was quite a cutup, got a tumbler of water and sprinkled the heads of everybody who never crossed before. Also, first-timers got themselves initiated into the Shortsnorters and started collecting bills from every country.

There were some fantastic collections of Shortsnorter bills along the ferry route. I even saw one with both Roosevelt’s and Churchill’s names on it. People paste their bills together with Scotch tape and as the string gets longer and longer, they make a roll out of it. Last spring, I saw a role in Cairo 35 feet long, but they say Adolph Menjou on a recent African trip build up one to 52 feet. Being a non-hobbyist, I hardly ever ask anybody to sign mine, but on the way over I’m sure I must have signed 500 for other people.

The man from Nebraska

In the five-day trip, we spent three nights on the ground and flew all night on two nights. At one midnight stop, American Army hostesses met us, took us to their quarters for a 15-minute refresher and some Cuba libres. At another stop in the hot tropics we were given breakfast by Maj. Bill Marsh, who asked me to put in the paper that at last I’d met somebody in the Army from Nebraska, and not only from Nebraska but Tekamah, Nebraska.

Believe it or not, Maj. Marsh couldn’t produce any proof there really is such a place, but he did have an honest face.

At another field, the starter on one of our motors broke down so they just wrapped a rope tightly around the propeller hub, tied the loose end of the rope to a jeep and then started the jeep driving away at right angles to the plane thus spinning the motor. Just the old spool-and-string principle on a larger scale. Worked beautifully every time, too.

A day’s quota of bombers

The Army’s vast ferry route to Africa is now beautifully organized. It runs with almost the precision of commercial airlines. Much of the scheduled flying is actually done by airlines on contract to the government while flying along side by side is a great flow of combat planes being taken to the front by their youthful Air Corps crews.

For security reasons, I can’t tell you the route we took or name any of the places along the way although it is already fairly well known to the public. You’d be impressed if you could see the hordes of bombers along the way. At one tropical airdrome, the field was covered by big planes and I asked the commandant why they needed so many bombers stationed there.

He said:

Oh, they’re not stationed here. They just came in this morning and are about ready to leave. That’s just our daily quota going through the front.

He sleeps to Africa

Of my four ocean crossings, this last one was the simplest and quickest. We made the actual overwater hop in a converted bomber and in only 10 hours, crossing against headwinds.

We passengers sat in old-fashioned hard seats like the first airlines used to have. The plane was cold and draughty so we all wrapped up in blankets. The front cabin was stacked full of cargo. There was a small toilet in the tail, right out in the open. Since there were two girls aboard, nobody ever went to the toilet.

It was nighttime when we took off. The dispatcher gave us a lecture on what to do in case we crashed at sea and made us put on Mae West lifejackets which we had to wear for 10 minutes after the takeoff. As soon as the 10 minutes were up, I took off mine and went sound asleep. When I awakened, we were only half an hour from Africa. That’s the way to cross the ocean.

U.S. State Department (December 7, 1943)

Cairo [?], December 7, 1943

After discussing this matter with the British military authorities I consider it inadvisable to reopen the matter at this time.

FDR

Roosevelt arrived at the airport at 8:05 a.m. and bade goodbye to Churchill and to certain Americans (Steinhardt, Kirk, Royce, and others), after which he embarked in the plane at 8:20 for the return journey.

Roosevelt discussed certain subjects with Churchill apparently on the last day of Roosevelt’s stay at Cairo. These subjects, which may have been discussed at the airport, were:

- Italian priests and nuns interned or detained in Egypt and in Ethiopia

- The question of seeking bases in Ireland

- British gold and dollar balances.

Cairo, December 7 (?), 1943

[I]

Some time back, in different circumstances from the present, the President approved a line of policy which would permit the British gold and dollar reserves to reach some figure between $600 million and $1,000 million. There was no agreement by the British to limit their reserves to this figure.

For some little time past the British reserves have exceeded $1,000 million, and may be increasing at a rate of some $600 million a year. This includes gold and represents their total resources against growing liabilities in all parts of the world, which amount to six or seven times these reserves.

This increase in the British reserves does not reflect an improvement in their financial position. Their quick liabilities, largely caused by heavy cash outgoings in the Middle East, are increasing at four or five times the rate at which the reserves against them have increased. Their net overseas position, in fact, is deteriorating at a rate of about $3-billion a year.

The increase in their gold holdings is due to certain receipts from South Africa and Russia. The increase in their dollar balances is due to their receiving the dollar equivalent of the local currency provided to meet the pay of American troops within the sterling area. Indeed, if it were not for the pay of the American troops the British dollar balances would be going down.

Apart from certain raw materials, the British are already giving reciprocal aid to the fullest extent of American Government requirements. They have now offered raw materials purchased by the U.S. Government in Great Britain and the Colonies on reciprocal aid terms. This would retard the growth of their balances by about $100 million a year, and by $200 million if India and Australia join in.

The British argue that some growth of their reserves is indispensable to the delicate system they are operating by which they finance the war on credit throughout a large part of the world, and that the retention of some part of the above receipts, as a support to this credit system and an offset to a much larger increase of liabilities, is not open to legitimate criticism. They point out that the Russians are believed to hold gold reserves nearly double the total reserves of the British and have no significant liabilities against them. But, in the case of Russia, it is not at present proposed to require them to surrender any part of their reserves as a condition of further Lend-Lease assistance.

The British feel that they ought not to be asked to agree to a ceiling to their balances, since their reserve position must be their own concern. Nevertheless, if the British argument is accepted as valid, the position could be regularised by a new Directive, which would set up a revised formula for the guidance of American Departments. If the figure given by the new formula was being approached, then the whole question could be re-opened.

The new formula might provide that an increase in British reserves is not unreasonable if the increase does not exceed, say, 30 per cent, of the increase of British liabilities.

Figures furnished to Congress hitherto have not disclosed the full burden of British overseas liabilities, or their rate of growth. It might be necessary to justify the new arrangement to provide that the information given to Congress in future should be fuller, and should show in some fashion, which would not be dangerous to British credit, the growth of liabilities as well as the growth of reserves.

26 October 1943

[II]

There is a matter affecting our financial relations with the United States of America which I think I must bring prominently to your notice at this particular juncture. We have reason to believe that the President is about to give a decision which is of absolutely vital importance to our financial capacity to get through the transitional period and, indeed, to our diplomatic independence during that time.

We are all concerned by the mounting accumulations of sterling balances in the hands of other countries. These represent a post-war liability upon us to convert the sterling into gold or other foreign exchange which the holders of the balances may need.

It looks indeed as though we may come to the end of the war with external liabilities of not less than £2,500,000,000 (ten billion dollars).

On the other side, after being almost cleaned out by the middle of 1941, we have been gradually building up a modest reserve. Our free balances of gold and dollars have now reached £300,000,000, and there is a reasonable hope of their reaching £500,000,000 (two billion dollars) by the end of the war, or about one-fifth of our assumed liabilities at the same date. These balances represent our only quick assets against the liabilities and constitute in fact the central reserve of the whole Commonwealth, since they include dollars turned over to us under the sterling area arrangements by the Dominions and other countries in the sterling area.

These balances will be absolutely essential to see us through the difficult transition period after Lend-Lease has ceased, and before the measures we shall have to take to restore the balance of our external trade have had time to bear fruit.

Early in the year we heard, almost accidentally, that the President had authorized a directive to the effect that the British reserves were not to be allowed to rise beyond a billion dollars (£250,000,000). It is not clear that this directive was ever issued in such explicit terms, and we were certainly not consulted about it. But the U. S. Treasury maintain that this alleged directive puts the Departments under orders to cut off Lend-Lease as soon as our total reserves exceed the limit of a billion dollars.

In course of time, this figure has been passed. Our reserves are now more than $1,200 million. From now on they are likely to increase, owing to our receiving the dollar equivalent of the pay of the American troops in the sterling area. According to present estimates of the numbers of American troops who will be drawing their pay in those areas, our reserves may increase by as much as $600 million in the next year.

This does not mean, however, that we are getting richer. Our liabilities are increasing five or six times as rapidly as our reserves, and we are constantly getting deeper into the pit of net indebtedness. Indeed, I doubt if we can maintain our external financial fabric on its present basis, unless some moderate proportion of our increased liabilities is covered by reserves against them.

All this has been explained in great detail to the American Administration. The late Chancellor of the Exchequer wrote a long letter to Mr. Morgenthau, rather more than two months ago, which the latter acknowledged and promised to answer. No reply has been received. When our Delegation was recently in Washington in connection with the currency and commercial talks, Lord Keynes and his colleagues submitted a memorandum to the State Department, the Lend-Lease Administration and the American Treasury on our balances and on our liabilities, asking the American Government to recognise that, in view of our growing external liabilities which arose directly from the war, the position of our balances should not be regarded as open to criticism. This view received strong support in some of the American Departments, though not in all. Mr. Stettinius and the State Department are wholly convinced that, in the circumstances, there should be no reduction of Lend-Lease, and that this small mitigation of our growing indebtedness should be allowed to accrue to us. The Lend-Lease Administration (at any rate before they were merged in the new body) were of the same opinion. The U.S. Treasury, on the other hand, has been taking up a sticky line, for reasons which have never been explained to us. They have shown a disinclination to discuss the matter with any of our representatives or to give any reasons.

Some elements in the Administration maintain that Congress was given to understand that Lend-Lease was only to apply to the extent to which the recipient countries were utterly unable to pay for imports, whether of food or military equipment. In other words, however great our liabilities, we are not entitled to Lend-Lease as long as we have a dollar in the till. This view might have been sustainable in some quarters before Pearl Harbour. But it is, of course, utterly contrary to the principle of the pooling of resources between Allies, and also to the principle that the most convenient supplier shall provide the materials, irrespective of financial liability.

Moreover, it is a doctrine apparently to be applied to us only, for no such suggestion has been made to Russia. Nor, of course, do we apply it in giving reciprocal aid to the Americans or to any other country.

To resolve the difference of opinion between his own advisers, the President set up, several months ago, an interdepartmental, ministerial Committee, to report to him. Owing to the difference of opinion on this Committee, no report emerged, and sundry meetings of the Committee were adjourned when the time came to call them. This position has gradually become intolerable from our point of view. As the U.S. Treasury takes the line that the existing Presidential directive must be followed until it is superseded, the Lend-Lease Administration is reluctantly and half-heartedly falling in with this by proposing to cut off various items of Lend-Lease, though on nothing like a large enough scale to keep our balances down to the prescribed figure. We have been urging, therefore, on the American Departments concerned that the matter should be brought to a head. During Lord Keynes’s recent visit, the State Department and the Lend-Lease Administration both agreed that this was the right course. Colonel Llewellin and Sir Ronald Campbell urged Mr. Harry Hopkins to bring it to a head. As a result, the President has instructed Mr. Morgenthau to expedite the Committee’s report.

It may be that this report is already in the President’s hands. In any case, it is absolutely vital to us that he should make the right decision when it reaches him.

There are several reasons for hoping that he will:

The force of our case, to anyone who takes the trouble to understand it, is overwhelming.

Russia’s gold and dollar reserves are nearly twice ours, and they have no liabilities against them. The Americans are not proposing to tackle the Russians with a similar proposal. We, however, are thought to be easier game.

A change of policy sufficient to keep our balances down to one billion dollars would have to be a very drastic one. The Americans will either have to ask us to meet the pay of their troops throughout the world (at a rate approximately double ours); or they will have to cut off Lend-Lease from some major item, such as food. At the very same time that the President has been emphasising the importance of our mutual aid, and when we have only just offered them raw materials, it would be a bit stiff to take either of these measures.

A favourable decision could take various forms. In no circumstances, of course, should we agree, on our side, to allow the amount of this country’s reserves to be settled by the Congress of the United States. But that is no reason why the President should not give instructions to his own Departments to the effect that they need not begin to worry about our reserves until they exceed a certain figure.

The most satisfactory revised directive would be one that fixes no limits, but asks that we should keep in consultation with the Administration about liabilities and balances. Failing that, if there is to be a ceiling, it should be raised to something not less than $2,000 million.

Apart from our post-war liabilities, which, as I have said, are likely to approach five times that amount, our adverse balance of trade in the first two or three years after the war will by itself exceed it. It is about the same amount as the Russian reserves, and they, as I have said, have no corresponding liabilities.

I attach a brief version of our case in a form which may have reached the President. This was prepared by Lord Keynes for Mr. Dean Acheson and Mr. Harry Hopkins, so that they could have something brief in their hands for use at an appropriate opportunity.

I again emphasise that an adverse decision would have the gravest consequences to our financial independence; whilst a favourable decision would remove a constant source of anxiety and friction.

JA

11 November 1943

[III]

Prime Minister

Great George Street, SW1

Secret

Thanks to gold from South Africa and pay to American troops in the U.K. and the Empire, our gold and dollar balances have increased to $1200 million and may rise to $2000 million by the end of the war. Much of the increase is not really ours at all but represents profits of Empire countries who choose to use us as their banker. Actually our reserves are far outweighed by our liabilities, especially in India and the Middle East, which are rising about five times as fast as our reserves and may amount to $10,000 million by the end of the war. Thus our net overseas position is deteriorating rapidly and our reserve when the war ends is likely to be only one fifth of our liabilities.

Certain Americans, ignoring these liabilities, claim that supplies on Lend/Lease should now be reduced and that we should be made to pay with our gold and dollars for goods supplied. Why they should pick on us for such treatment is not clear; it is never suggested that Russia and France with their enormous gold balances should pay for goods supplied to them.

The Lend/Lease administration who, with the State Department, are favourable to us, are reluctantly proposing to cut supplies since the United States Treasury maintain that the President issued a directive limiting British reserves to $1000 million.

The President has appointed a Committee to examine the matter, whose report may be already in his hands. It is vital to us that he should make the right decision. If our Lease/Lend supplies are cut off and our balances reduced to $1000 million, it will be almost impossible for us to tide over the difficult post-war period while we are building up our export trade.

CHERWELL

12 November 1943

| Present | ||

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | Turkey | |

| Prime Minister Churchill | President Inönü | |

| Foreign Secretary Eden | Foreign Minister Menemencioğlu | |

| Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen | Mr. Açikalin |

740.0011 EW 1939/12–2443

December 7, 1943

Most secret

The Prime Minister put to President Inonu the proposal that by February 15 all measures should be taken to render possible the fly-in of the 20 Allied squadrons. The Prime Minister would be ready after February 15 to consult with the Turkish government before the fly-in is carried out. By that time the situation may have evolved. The Balkan satellites may be on the point of falling out of the war. We should expect all measures to have been taken by February 15 to render the fly-in possible. It would not be possible to forecast enemy action between now and February 15. The President of the United States had said that Germany would be given no excuse to attack Turkey in this interval. Germany would not consider excuses but only whether it was worth her while to attack Turkey. Therefore by February 15 we shall know more about the German reaction. We have agreed on the preliminary steps and the work on the airfields must be finished as quickly as possible. After that on February 15 if the preparations are complete, he will ask whether the squadrons can come in and the matter can be discussed as between friends and allies. If after February 15 Turkey will not receive the allied squadrons and wishes to prolong the discussions of the equipment of the Turkish army, then the Prime Minister will be forced to think of other plans. The allied squadrons cannot be wasted, they would have to be used elsewhere. February 15 will be the critical and serious moment. But if we are forced, after that, to send the squadrons elsewhere, the question cannot be reopened with Turkey. It must be closed. We should have to tell our other allies that our policy with Turkey had failed. If the Turkish answer is favorable we would begin as quickly as possible to send in further material. But before February 15 Turkish communications would be blocked with the material for the airfields. It was the Prime Minister’s opinion that Bulgaria would not attack and it was even uncertain whether the Germans would push Bulgaria to attack, because if Bulgaria did so she would have to withdraw her nine divisions from Yugoslavia and this would create difficulty for the Germans.

President Inönü understood that the Prime Minister had resumed [rèsumèed] the conversations of the last 2 or 3 days.

M. Menemencioğlu said that the Turks had said all they had to say in the last three days.

President Inönü said that he had the impression that on the essential question both sides had reserved their own opinions. The Turks had foreseen two periods (i) preparation and (ii) effective cooperation. This had been accepted by the National Assembly and had formed the subject of the answer of November 17 given by the Turkish Government. On the other hand the Prime Minister considered the first period as purely one for preparation especially as regards the airfields.

The Prime Minister explained that this was because he did not regard invasion as a serious danger.

President Inönü asked whether he had rightly understood that the Prime Minister had not excluded the supply of other goods either before or after February 15.

The Prime Minister said certainly not. The quicker the supplies were sent the better.

President Inönü asked whether the Prime Minister thought that these supplies should be complete before action was taken.

The Prime Minister said that it was not necessary that the supplies for the army should be complete by February 15th, and for the Turks to insist on this would be the same as saying that they would not come in. To complete supplies for the Turkish army is to adjourn the final Turkish decision indefinitely. On that basis the chance of shortening the war by Turkey’s entry would be lost.

President Inönü said that he thought the difference between the two sides was in their appreciation of German strength. The Allies thought that in the present situation Germany could not do much harm to Turkey.

The Prime Minister said that this applied only to land attack: air bombardment was very possible.

President Inönü said that all war risks were natural and would have to be taken. The Turkish government saw Germany as stretching from the Crimea to Rhodes and with Turkey encircled and they felt that Germans [Germany?] had fresh forces with which she could attack. If in these circumstances Turkey was left without a minimum of the essential supplies she would be seriously menaced on land. He explained a weak point in the present Turkish military position. At the beginning of November one class had been released from the colours. A new class of recruits was now being called up. On the basis of a decision by February 15th, Turkey would have to strengthen the army by 2 or 3 classes. Another point was that at the present date, the period of mud in Thrace had not yet begun. The President went on to say that he had explained the situation as he saw it. His technicians were not with him and he could not go further into detail. It was a serious question for the government to give a positive answer on matters which went against the decision of the Grand National Assembly. As to the political question in the preparatory period, it was necessary to work for a closer definition of the political situation. If he had understood the Prime Minister rightly, Mr. Churchill required his answer now, or soon, so that the situation to be taken up in the future could be defined. He would do all he could to give a clear and accurate answer in 3 or 4 days.

The Prime Minister said that the final answer was not required till February 15th, but that in the interval we must at once begin preparations.

President Inönü understood the position. The answer he proposed to give in 3 or 4 days was to the question whether and in what manner he would engage in the preparations. He would tell us the conditions in which Turkey would come in or take the risks likely to bring her in. After having considered the Prime Minister’s statement Turkey must give an answer. The President asked that an expert should be sent to Angora to study the technical questions more closely. The Turkish answer had been given in principle. The Turkish government thought that a general plan was necessary, not for the sake of prolonging the discussions but for practical reasons. It was the Prime Minister’s opinion that the preparations proposed up to February 15 were sufficient. In the interval it would be quite possible to form a general plan.

The Prime Minister said that if the President envisaged a long programme of reequipment taking into account the difficulty of communications and so forth, that was the same as saying that the negotiations were ended. It would be easy for Turkey to make prohibitive conditions and in that case the Allied forces must be sent elsewhere.

President Inönü said that this was a serious statement touching a fundamental point. He would define the position as follows:

a) given that the Turkish answer is a simple acceptance of the Prime Minister’s proposal, namely to go on with the preparations till February 15 and taking the final decision then, that would be the best answer that the Prime Minister could require.

b) alternatively to consider Allied needs and add the Turkish need for a plan which both sides could accept. If Turkey accepted, the preparations could continue; if not, the Prime Minister would have the right to change his plans.

The Prime Minister remarked that this would mean a complete change of policy. In that event the war would move westwards and Turkey would lose the chance of coming in and of reaping the advantages which entry into the war would promise her.

M. Menemencioğlu asked whether by change of policy the Prime Minister was referring to the Anglo-Turkish Alliance.

The Prime Minister replied that the Alliance would cease to have any value for war purposes. The moment would have gone when Turkey could render the great service we asked. Turkey would stay where she was. Friendship would remain, but as an effective ally for the war Turkey would count for nothing. We should win, but without Turkey. Turkey’s entry into the war was important for us as it gave a chance of including Turkey with the Allies in the future.

President Inönü said that for Turkey fidelity to Great Britain was an essential conception both during and after the war. If this was also the British view he thought it was not impossible to find a solution.

The Prime Minister mentioned the line of procedure as subsequently handed to the President and shown here as Annex A.

Mr. Eden said that as regards the Alliance we were faithful to our engagements and wished to work with our Turkish friends. But if the time for Turkey’s entry into the war came and went, it was inevitable that the spirit of the Alliance would be affected.

The Prime Minister expressed the view that Bulgaria would not attack Turkey when she knew that this would entail a Russian declaration of war on her.

M. Menemencioğlu asked whether the Russian declaration of war would be given equally if Bulgaria allowed Germany all facilities in and through Bulgaria for an attack on Turkey.

Mr. Eden undertook to put this question to the Soviet government.

The Prime Minister said that he could not guarantee that the Germans would not bomb Istanbul and Smyrna. But if our squadrons were there the Germans would have serious losses. He thought it very possible by the end of February that the situation would be reassuring for Turkey. It would be easier to see clearly then than now and in the interval the preparations did not commit Turkey to give a favourable answer to our appeal to send air squadrons after February 15. The President was quite free to say yes or no without reproach. All that would have happened would be that we had sacrificed war material for nothing. If Germany did not attack Turkey but remained in relations with her, we should not ask Turkey to declare war. Time would thus be gained for sending in further supplies. In this way Turkey would be in a very strong position and would emerge unexhausted with the advantage of cooperation with the victorious allies. The Prime Minister wanted Turkey to be strong after the war and to be friends with Great Britain, the United States and Russia. Turkey and Great Britain had common interests and the Prime Minister wanted to protect them. The Prime Minister then handed the annexed paper to President Inonu who read it and said that it was clear and that there was nothing more to say. The Prime Minister pointed out that there were two things to be done. The President would consult the National Assembly and give his answer in 4 or 5 days. Those days could also be employed in pressing on with preparations and sending in specialists. This was agreed to and the number of specialists was limited to 250. At this point the Chiefs of Staff joined the meeting and handed the Prime Minister a paper which showed that between now and February 15th, in addition to the supplies required for the AA guns and airfields, a total of 58,900 tons could be sent to Turkey by rail for Turkey’s own use, given the full cooperation of the Turkish railways and in addition as many more supplies as could be carried by sea. It was agreed that the next steps should be the following:

British experts should go to Angora. This was agreed to by the Turks.

General Kiazim Orbay and General Ceffik Cakmak and a naval representative of the Turkish General Staff should come to Cairo. The Turks reserved their final answer to this question till their return to Angora.

Matters should then be followed up by the despatch of more British officers to Angora to continue the conversations.

ANNEX A

15 February. Allies ask permission to “fly in.”

if reply negative.

Allies direct all resources to another theatre and must abandon hope of wartime cooperation with Turkey.

if reply “Yes.”