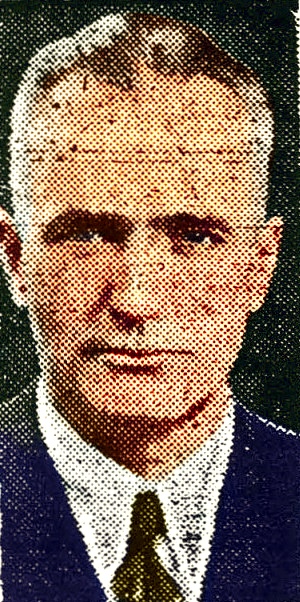

Clapper: Battle eve

By Raymond Clapper

The following dispatch from Mr. Clapper, written on the eve of the Marshall Islands battle in which he lost his life, was received a few hours after word of his death.

Aboard an aircraft carrier, somewhere in the Pacific – (by wireless)

On the night before a battle everybody gets a big holiday dinner. For breakfast on the morning of a battle beefsteak is served.

Everybody aboard knows when the time of battle is approaching. You begin to count the days as “D minus four,” “D minus three,” meaning four days or three days before the action is to begin. Sometimes, instead of calling it “D-Day,” they call it “Dog Day.” And for some time after a battle begins, the days are known as “D plus one day,” or “D plus two days,” instead of by the days of the week or month. The calendar is forgotten, and all time is counted as before or after the beginning of the battle.

A slow, almost imperceptible rise of tension takes place as D-Day approaches. But it is nothing very marked. Men begin to think more about their steel helmets, and to place them where they can be picked up quickly. At night you begin to have your red waterproof flashlight always within reach, and always in your pocket when you are moving about the ship. Some men keep heavy leather gloves in their pockets, because these are good to out on if you have to slide down a rope going overboard.

Always study landmarks

You are always studying the location of ladders, hatches and bulkheads, and making mental notes of little landmarks around the ship so that you can find your way in a hurry in the dark with only a dim red flash to guide you. It is surprising how different ship passageways seem when you try to find your way around them with the lights out, and when many of the openings are closed.

Some 3,000 men are aboard this ship, and when the call to battle stations is sounded, they must get to their places within seconds, or minutes at the most. Some of them must go the whole length of the ship, which is as far as a golf ball is ordinarily driven. Men are rushing both up and down narrow ladders. Hatches are being slammed. There is intense activity everywhere, with the general-quarters gong clanging its unmistakable warning of approaching danger.

Formerly ships would throw huge quantities of things overboard before going into action – all the mattresses, bedding, and other inflammable material. Now, with the vast improvement in fireproofing materials, and with greater fireproof construction and firefighting equipment, seldom is anything thrown overboard. there is very little around to burn.

Precautions at sea

Before I left Washington, one of the survivors of the carrier Wasp, LtCdr. William C. Chambliss, gave me a copy of his article, “Recipe for Survival,” which has been issued by the training division of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics. I find that many of his suggestions are being commonly adopted aboard this carrier, such as waterproof flashlights, heavy gloves, a large steel knife in a scabbard hitched to the belt – which is useful, as Cdr. Chambliss says, in cutting yourself clear of lines or other impediments with which you may become involved in the water, and also for discouraging sharks or for opening emergency ration cans.

Those are the kind of normal little preparations everyone makes, although the conversation seldom touches on the possibilities of action. The laughing and joking go on as usual at mess and around the ship, with boys scuffling on the flight deck and the hangar deck, or playing cards, or sleeping under the planes, during slack times.

You always snatch a nap if you can, because in a combat area you are up long before dawn and until late at night, and there is considerable tension, at least subconsciously.

During battle, when the men are held at their stations for long hours, mess attendants carry sandwiches and coffee to them frequently, also hot soup, lemonade, fruitcakes, and various small items they can put into their pockets and nibble at while beside their guns.

The briefing lectures

For several days before an action, the pilots spend hours listening to briefing lectures concerning the impending battle. They are told what they need to know in order to carry out their part of the battle. Especially they are given lectures about the territory they are to bomb or strafe. They are told about the history of the locality, the characteristics of the natives, the estimated strength of the enemy, and they make a careful study of aerial photographs and maps to mark the location of enemy airfields and other installations that may be targets.

But there is not the high tension that you might expect. Sometimes, when a report of exceptionally heavy enemy strength is given, there will be raucous shouts of “Wow!” Once when the briefing showed our own forces to be far in excess of what the enemy would have, somebody shouted from the rear of the room:

Let’s go on to Tokyo while we’re at it!

But mostly the pilots are slouched down in their chairs, their favorite position being with both feet up on top of the high back of the chair in front. They act much like a bored classroom taking in a lecture with as little effort as possible, instead of fighting men some of whom will not come back from the missions under discussion.

You have a sense of living in a world apart from what you knew at home, and there is almost no talk of life back in the States now. You live only minute by minute through the routine that carries you smoothly, as if drifting down a river, toward the day of battle.