WPB denies plan to cut production of American flags

…

His submarine, damaged by air bombs, trails convoy and scores on 3 vessels

…

Celebrating the 4th

It is now 167 years since a small group of men, representing 13 Colonies stretched along the Atlantic Seaboard, declared as a fundamental principle of government that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

On this anniversary of the birth of democracy in a new land, the American people may appropriately give some thought to the question of how faithful they have been to the ideals which found such brave expression in the moving words of Thomas Jefferson.

Have they been worthy of the men who pledged their all in order to build a new world based on an untried theory and of the men with flintlock guns who fought at Saratoga and Monmouth and Yorktown to translate this dream of freedom into reality?

Have the Americans of today, the inheritors of bright traditions, met the challenges of their times with the same spirit displayed in other crises – New Orleans, Gettysburg, Shiloh and the Argonne – when the cause of liberty hung in the balance and could be saved only by the shedding of the blood of young men on fields of battle?

These questions may be asked today without fear and answered truthfully and with pride. There has been no change in the breed of Americans since that memorable day in 1776, when 56 valiant men gathered in Philadelphia, cast off the yoke of kings and decided to fight for the fulfillment of their dreams.

The answers are to be found in the presence of eight million young Americans on a score of battlefronts in all parts of the world and in camps and on training grounds in their own land. They do not wear buff and blue or buckskin. They do not carry powder horns and long guns. Nevertheless, they are the spiritual kindred of these earlier Americans who, 167 years ago, shook the complacency of kings and gave a lift to the tired spirits of oppressed men everywhere.

This Independence Day of 1941 assumes a new significance and a new poignancy. Wherever the day is known – in the conquered lands of Europe, in China, even in Germany and Italy – it symbolizes freedom and democracy.

When the war has been won and a new world order has been shaped, something far different from that conceived in the mind of Hitler, who envisioned a master race and one of slaves, the dream of freedom that animated the 56 men in Philadelphia will become a thing of reality to millions who now live under the oppressor’s heel.

The Pittsburgh Press (July 4, 1943)

By Ernie Pyle

North Africa –

The Red Cross has a few critics but they are few indeed. The wonder is that it gets its job done at all, considering the conditions under which it has to work.

When the Red Cross opens up a new war theater, its growth has to be as fast as the growth of the Army. The way clubs spring up overnight in newly-occupied centers, the way restaurants and dances and movies and clubmobiles and hospital workers mushroom into life all over a new country, is something that still astounds me.

Bill Stevenson, the Red Cross delegate to Africa, wouldn’t admit this himself, but actually his job is to do things for the Army in spite of the Army. Not that anybody is against the Red Cross. It isn’t that. But the Red Cross has depended on the Army for a great many things – for jeeps, and boat priorities, and requisitioned buildings, and permissions of many kinds – and each of these is guarded by some individual whose job is to conserve things for strictly military use. The result is a fine art of wheedling on the part of Mr. Stevenson. But things do get done.

We who have written about the Red Cross in the past have usually centered upon the fine clubs it operates in all the big centers where troops are stationed. And yet actually – and I didn’t know this until a few days ago – the club part comes third in the list of things the Red Cross does in Africa.

First and foremost is the hospital program. The Red Cross has women workers with every hospital in this theater – five each at the big ones, three at the smaller ones.

Second is the field program. This is run by men, who live and work with combat outfits. They dole out books, towels, toilet sets, writing paper – all the little things the soldiers lose in battle. They are horns of plenty and father confessions and Johnny Fixer-Uppers.

They are the ones who wire home to see if Pvt. Joe Smith has become a papa yet. They bring the sad news that a soldier’s mother has died at home. They talk things over and get a neglectful boy to write home.

Through these field workers, the soldiers have direct contact with America in cases of family emergency. It’s surprising the number of cases they handle. Every day, 250 cables and 300 letters start across the oceans, solving soldier’s problems – it takes seven American girl stenographers typing constantly to keep these messages flowing.

The field men conduct 26,000 interviews a month with soldiers, advising them about allotments and other things.

The most spectacular Red Cross activity, although third on the program, is the club service. Today the Red Cross has more than 40 clubs in North Africa. These aren’t just little reading-room affairs – they’re hotels of four or five stories, serving meals, providing beds, and equipped with snack bars, lounge rooms, dances, and movies. Running all this is in a minor way the same as running an army. It’s a terrifically big business.

The Red Cross has 365 Americans over here now, and 100 more are due shortly. It has hundreds of local employees. 60% of the Americans are women.

No matter what deep services the Red Cross may perform, Stevenson says it’s the touch of femininity that does the soldiers the most good. Despite his metropolitan background, Bill has been naïve all his life about the influence that women wield in this world. He has found out in Africa.

Bumpy (Mrs. Stevenson) laughs and says that’s the outstanding thing Bill has learned in his war career – he has awakened to the powerful existence of womanhood.

He has found it out in two ways – one, the touching approval and desire of the soldiers for female companionship, even if it consists of nothing more than standing and looking at an American girl behind a counter; and, two, the rather laughable troubles he has with his staff in matters of the heart.

Bill has what he calls “colonel trouble.” It seems his gals are always getting engaged to colonels. You’d think a man old enough to be a full colonel would either be well married and settled or else determined to be an old bachelor. But no. Colonels moon around the Red Cross workers like country swains and the first thing you know they’re betrothed, begorra.

There’s no rule against Red Cross girls getting married while overseas, but there is a rule that they can’t be stationed in the same area as their husbands. One general, who has a colonel about to get married on him, says he will consent only on condition that they will be stationed a thousand miles apart.

Bill Stevenson wonders whether it’s going to be the general’s duty to keep the colonel-husband away from his wife, or his [Bill’s] duty to keep the Red Cross wife away from her husband. I suggest that Bill and the general make up a pot between them and hire a small Arab boy to stand watch.

LIFE (July 5, 1943)

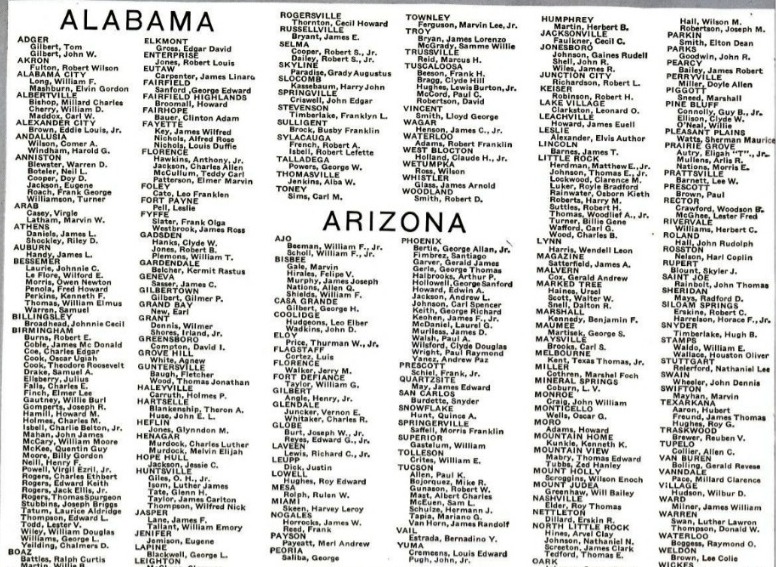

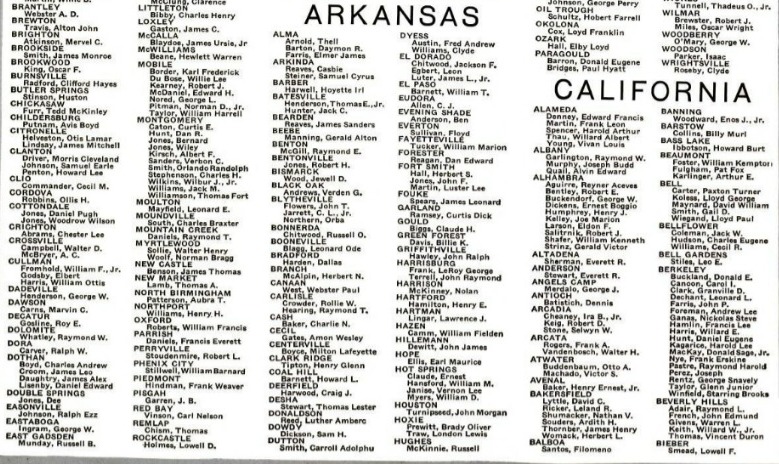

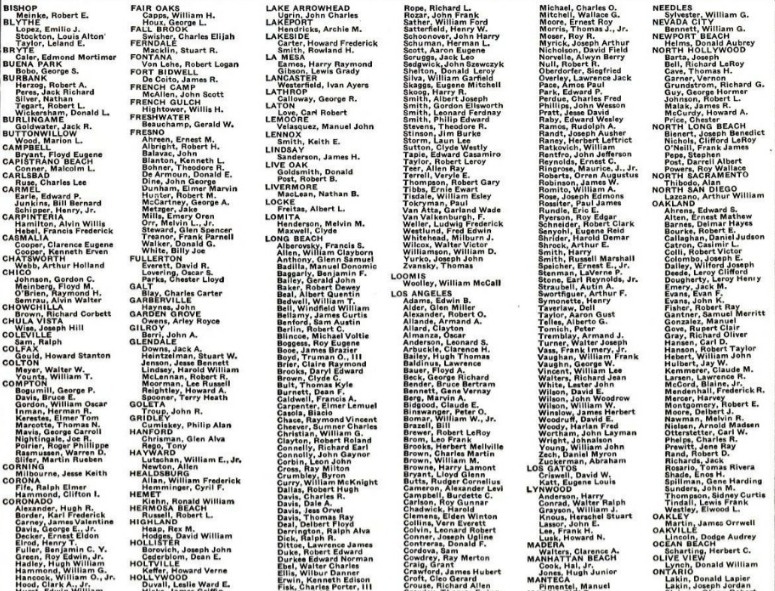

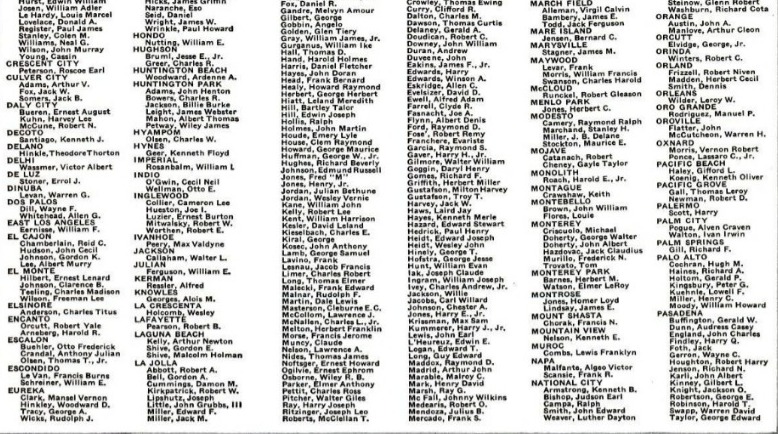

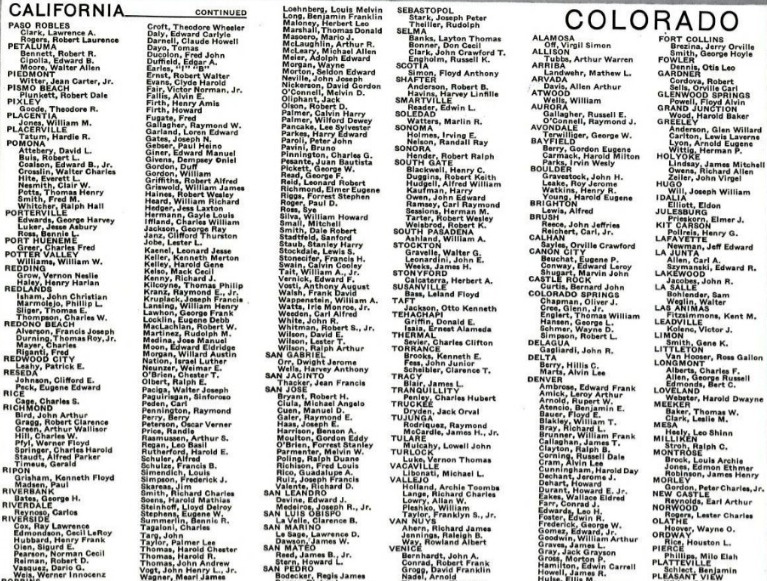

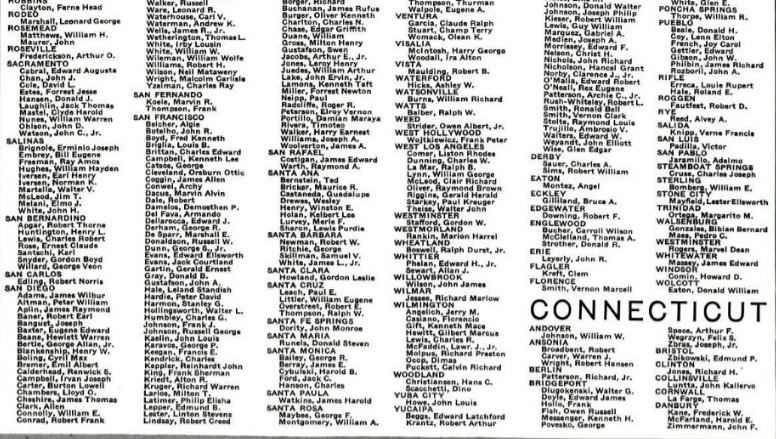

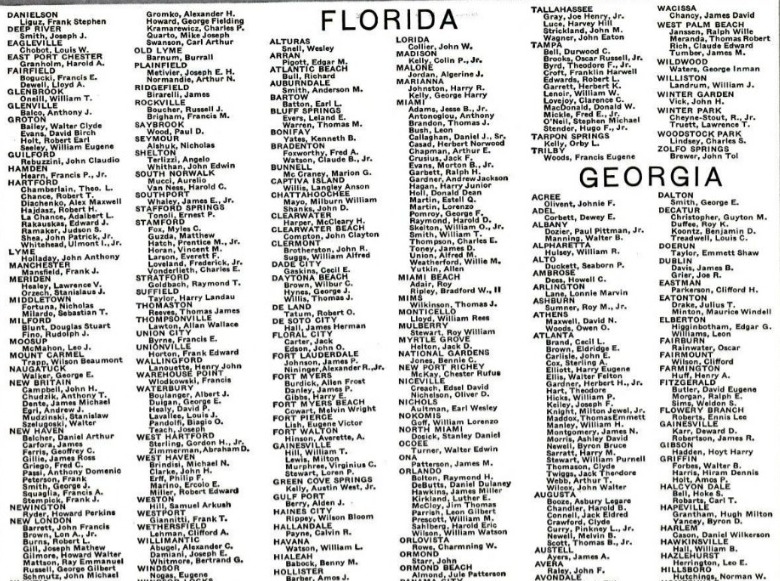

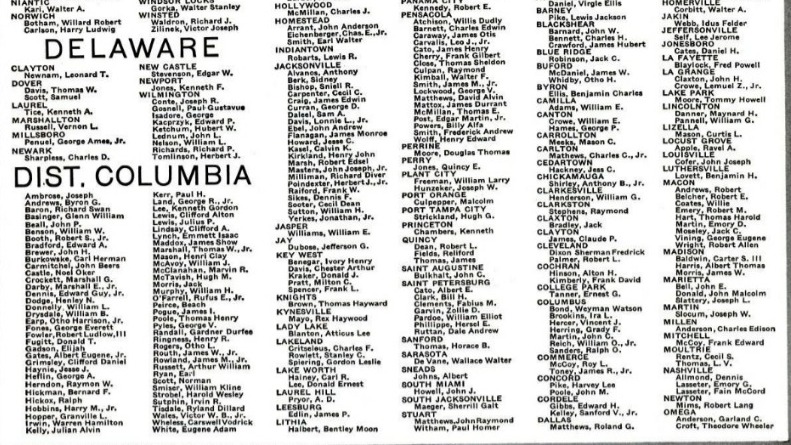

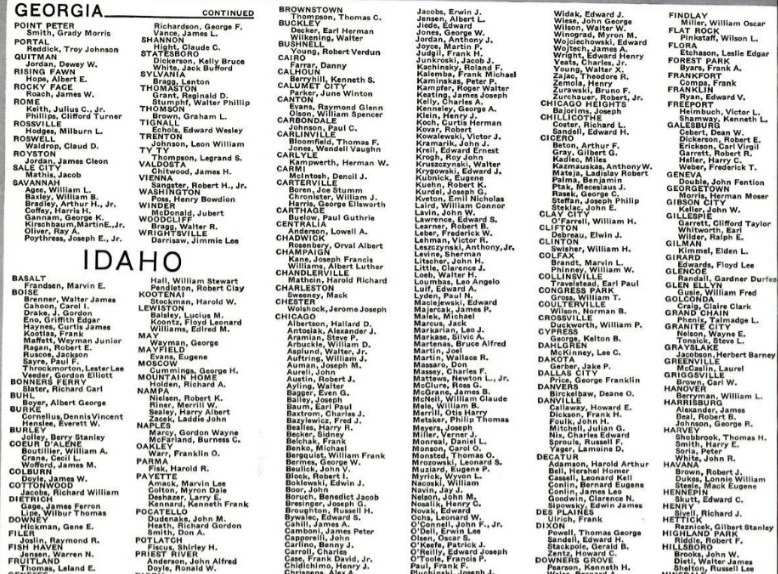

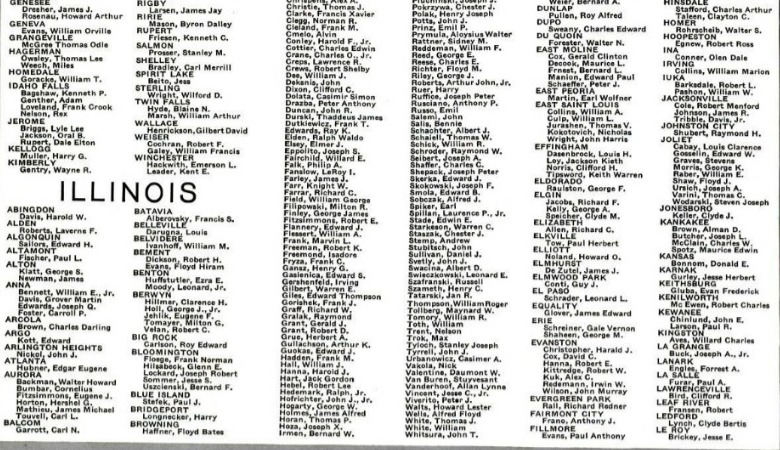

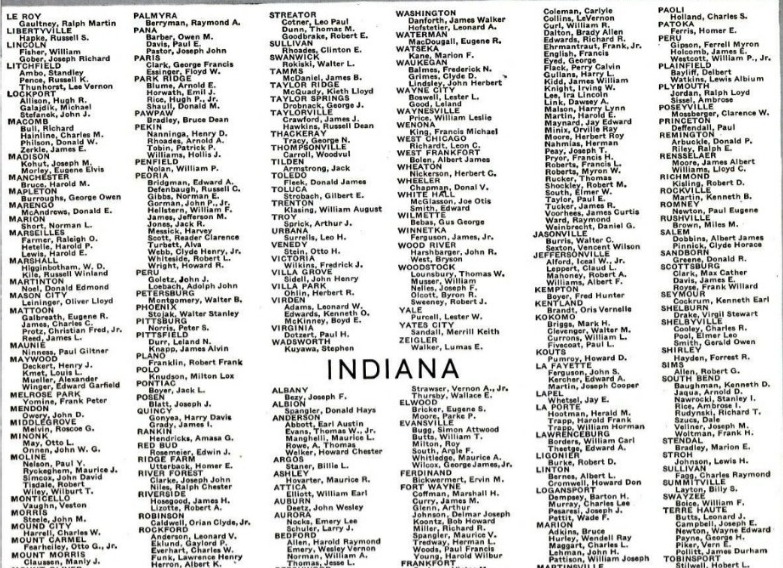

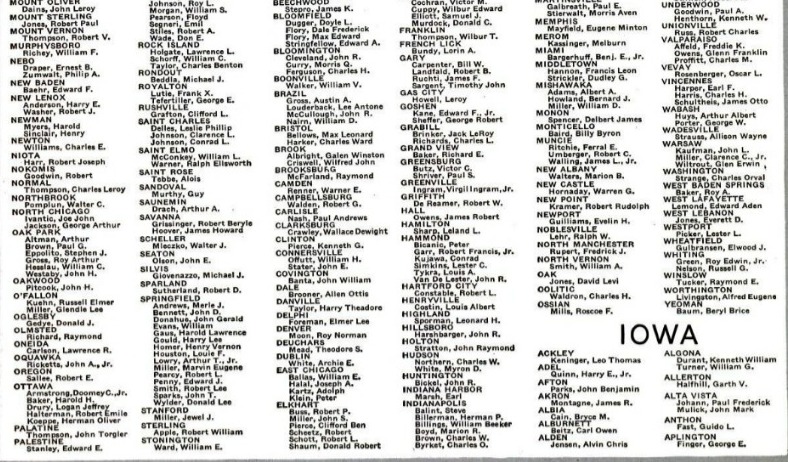

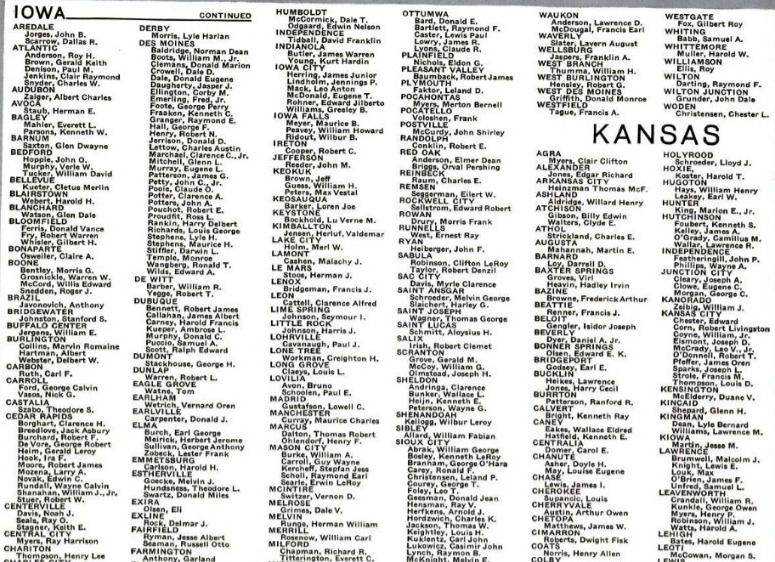

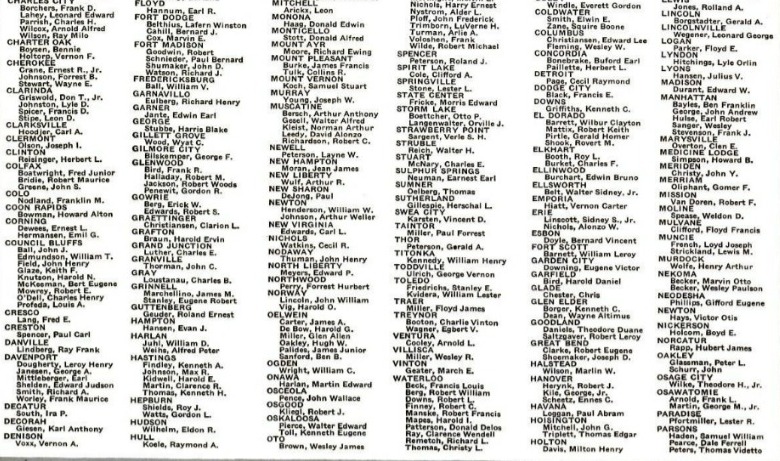

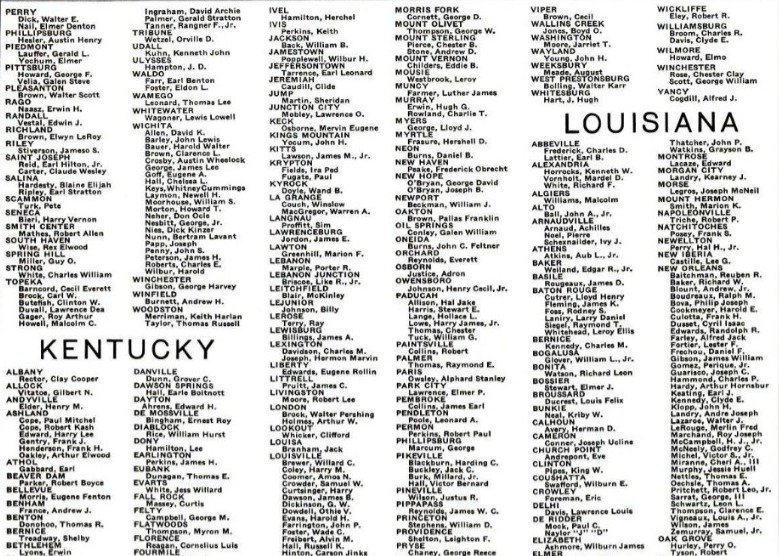

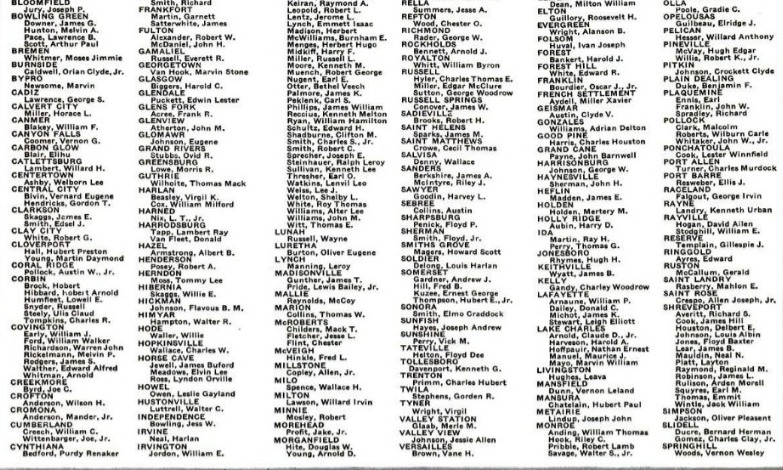

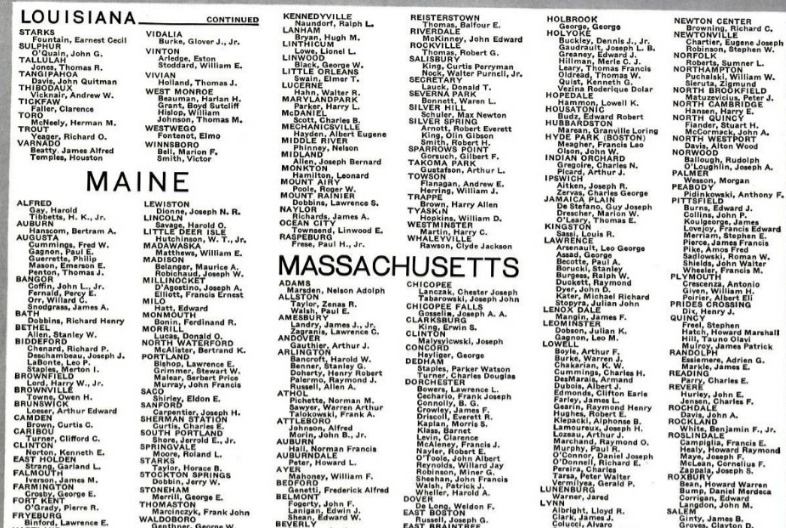

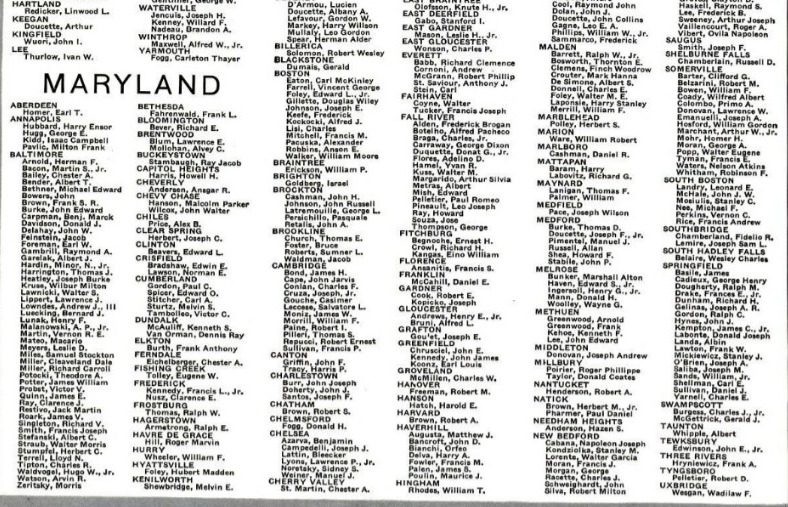

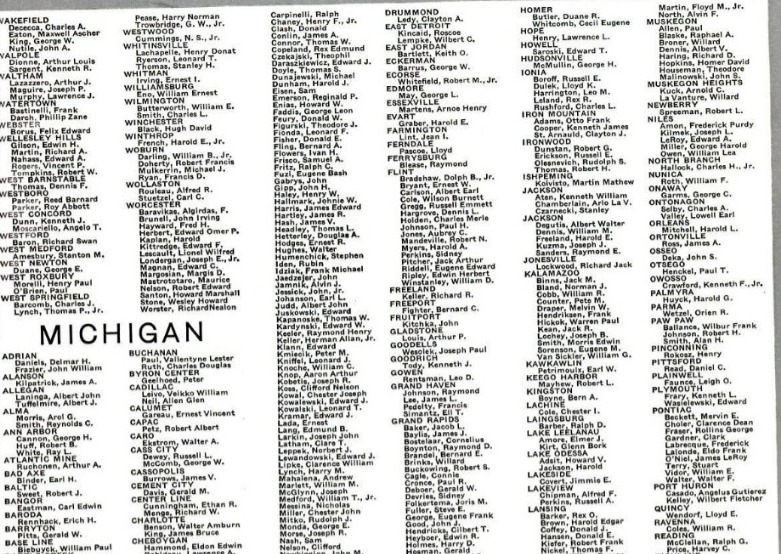

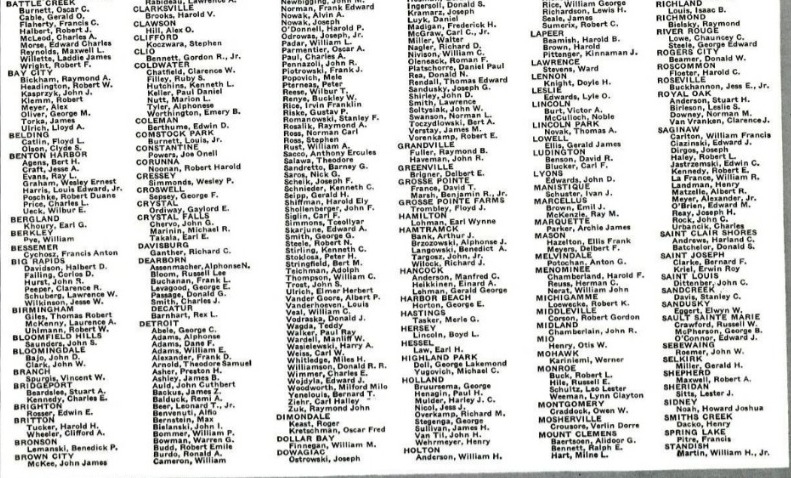

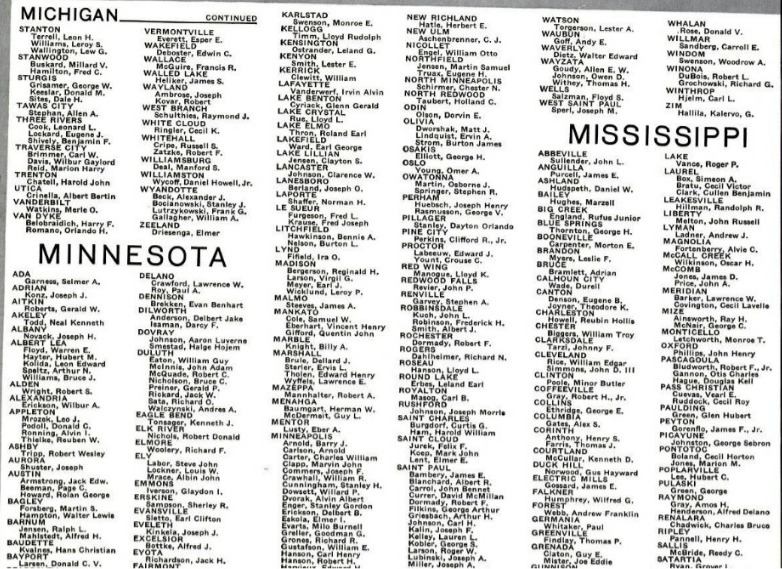

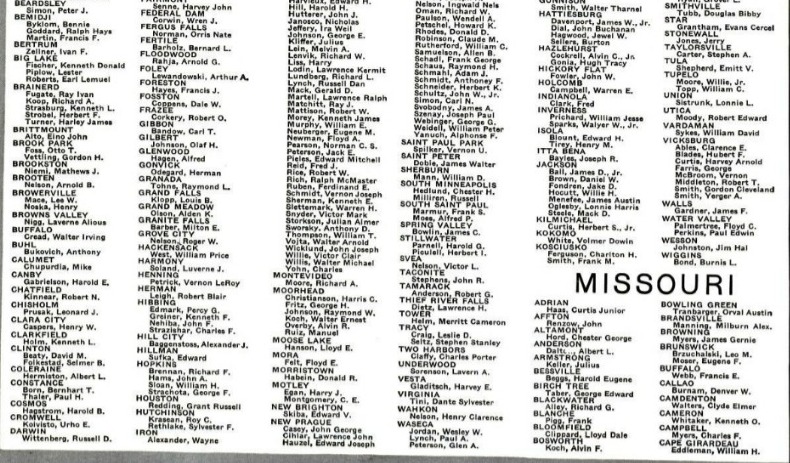

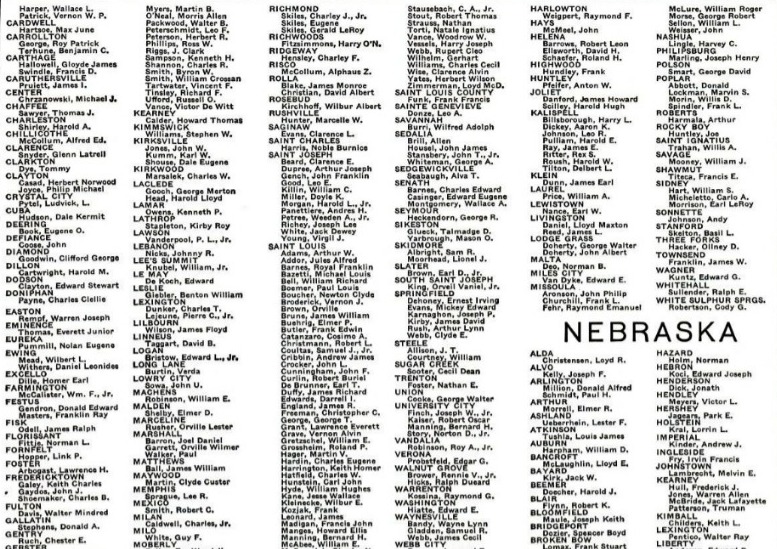

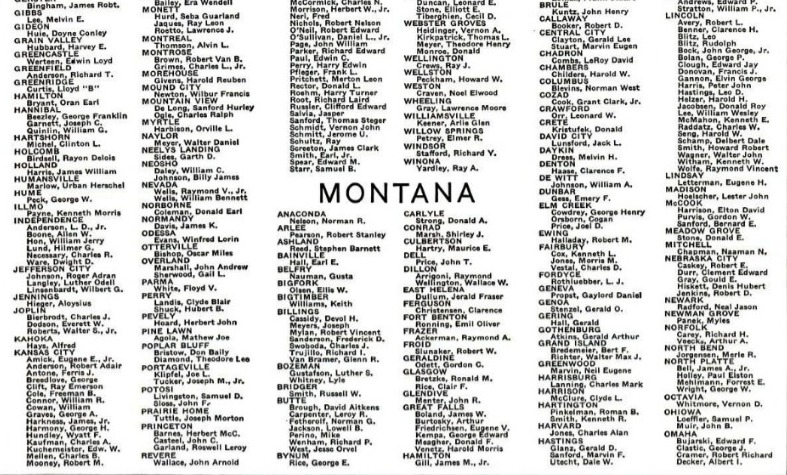

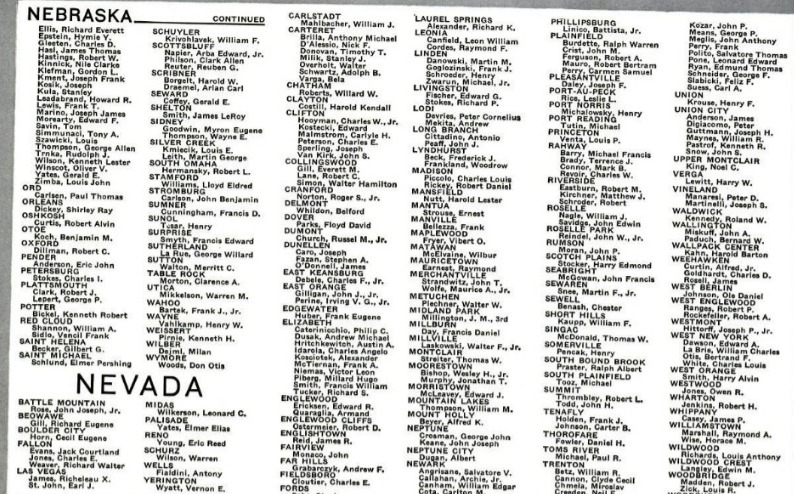

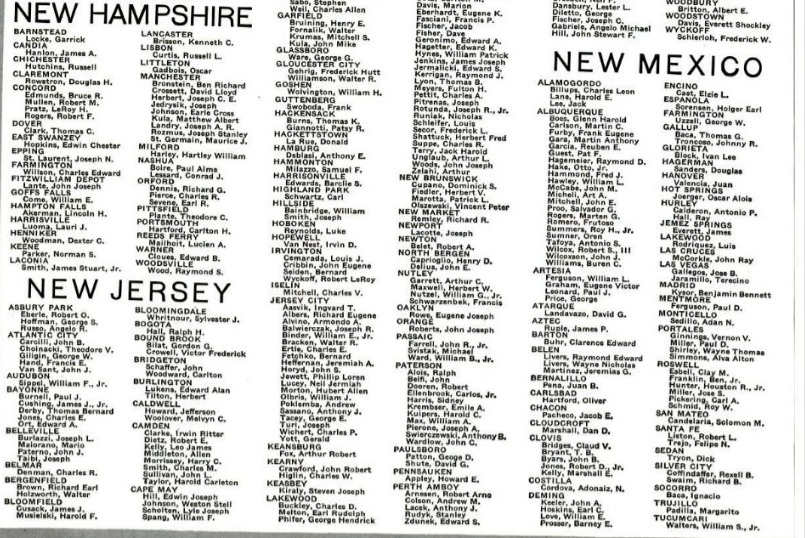

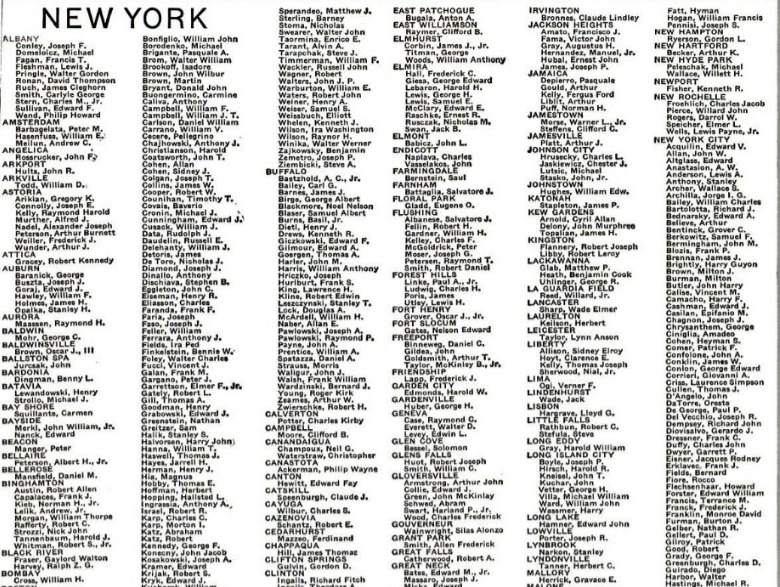

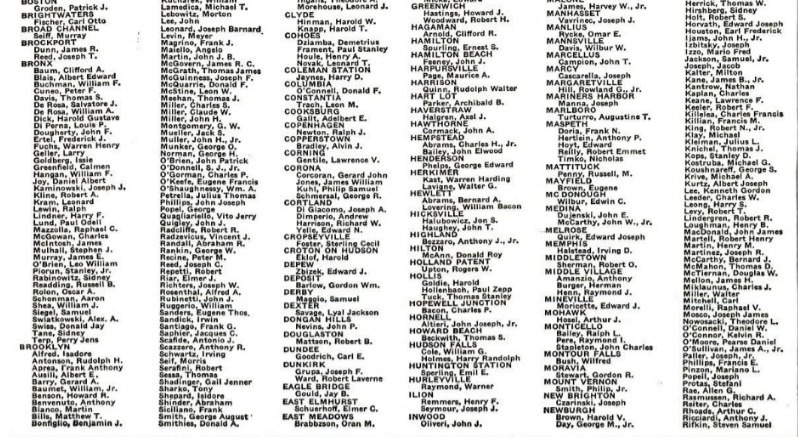

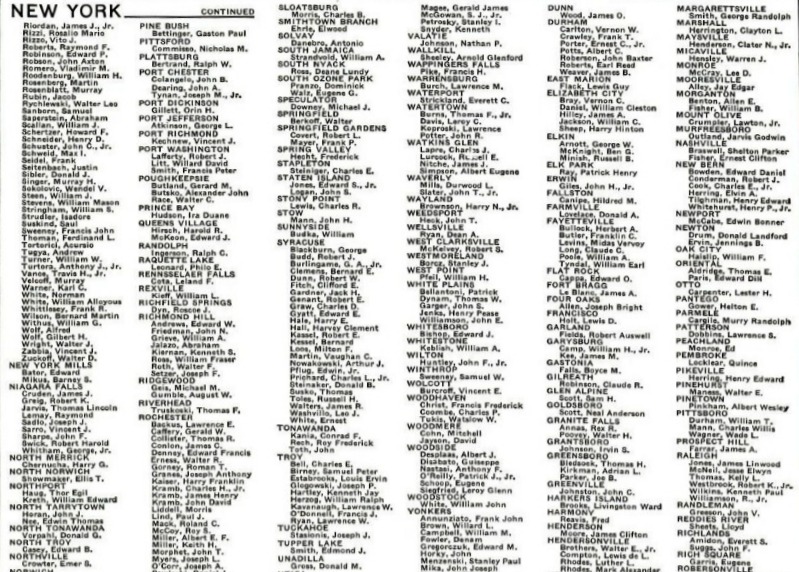

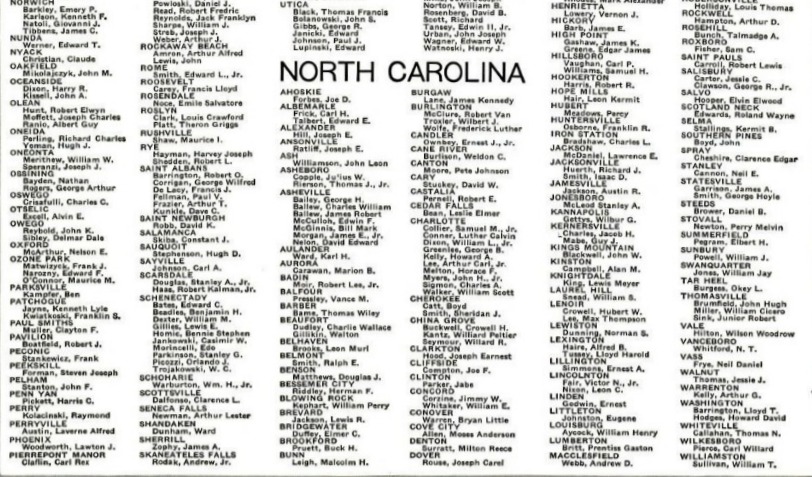

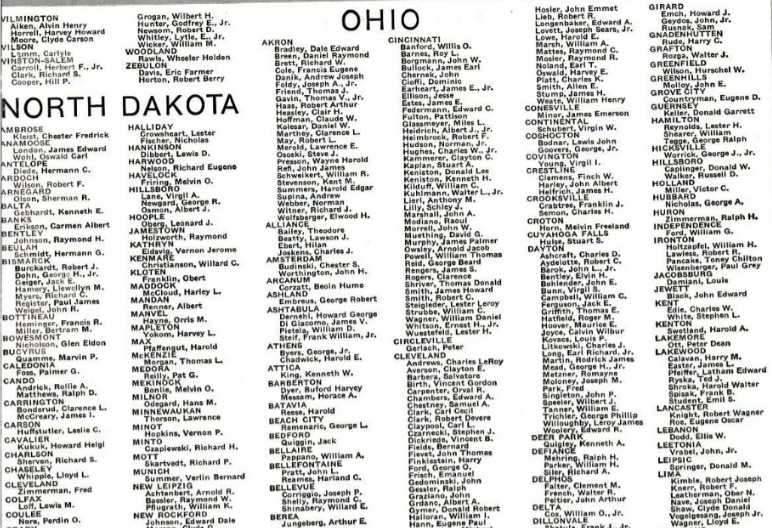

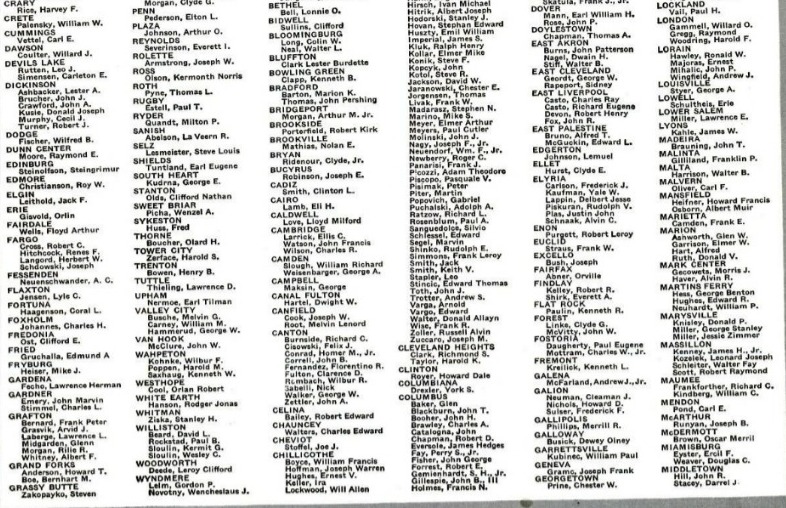

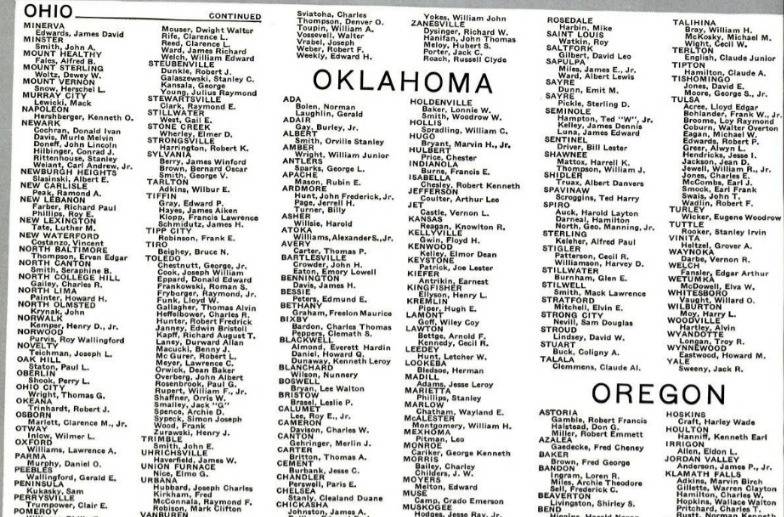

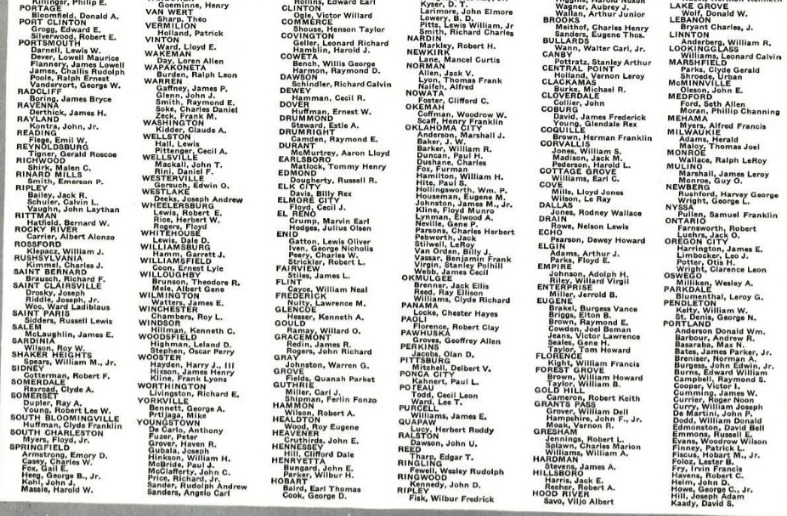

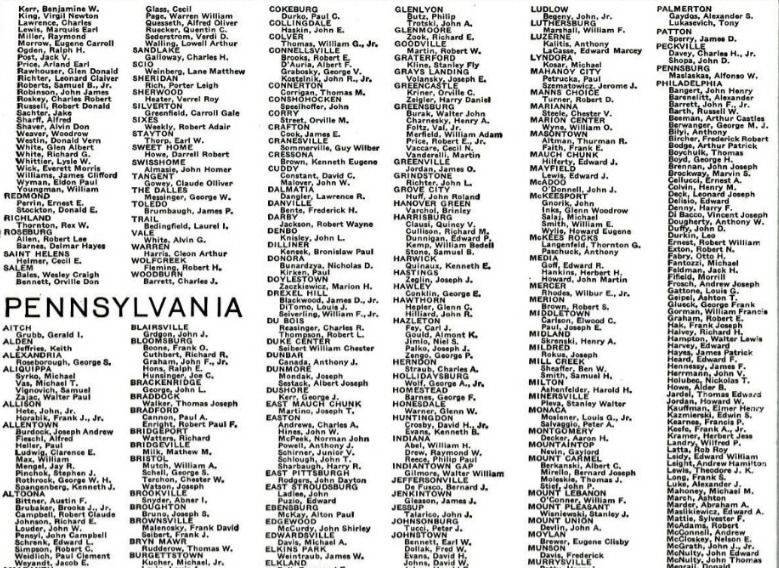

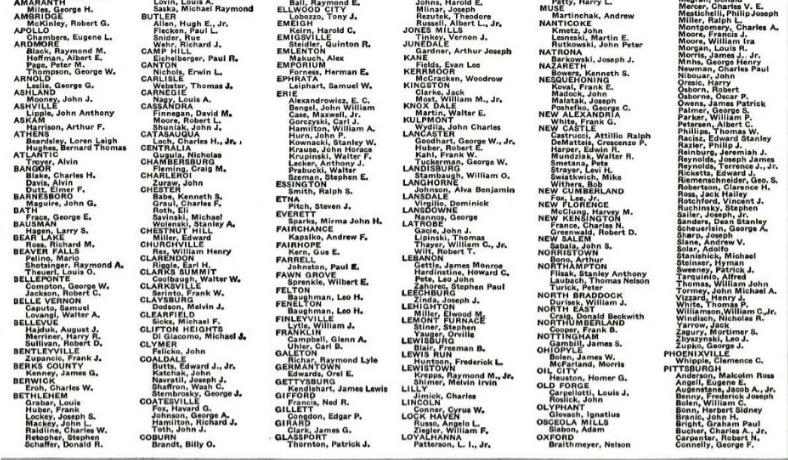

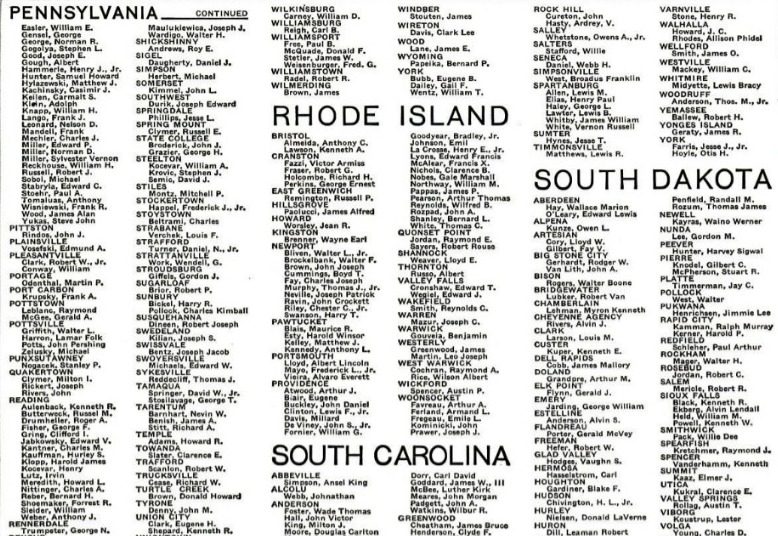

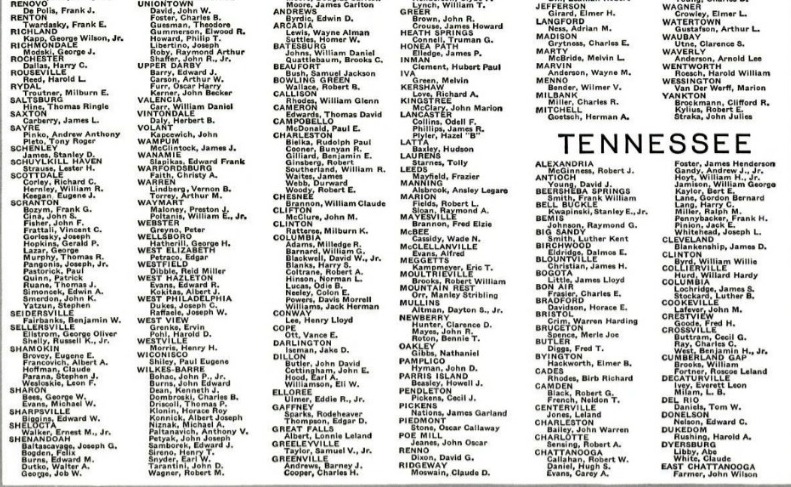

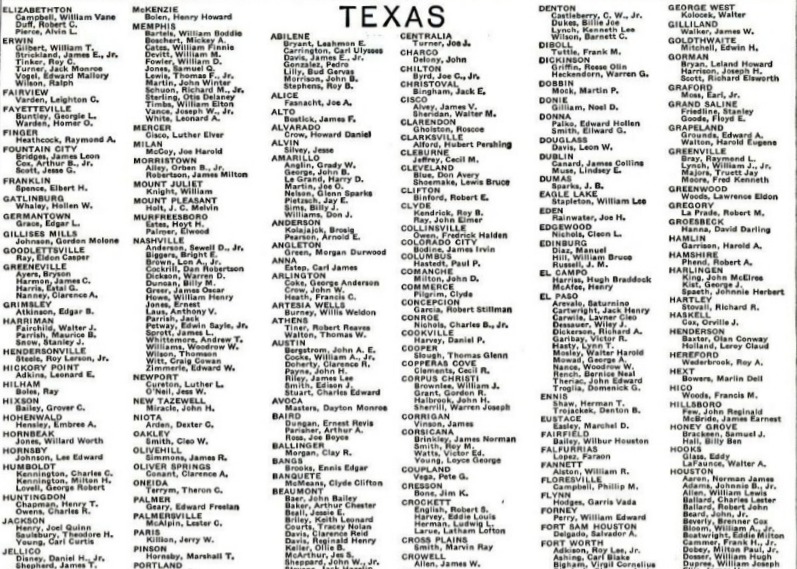

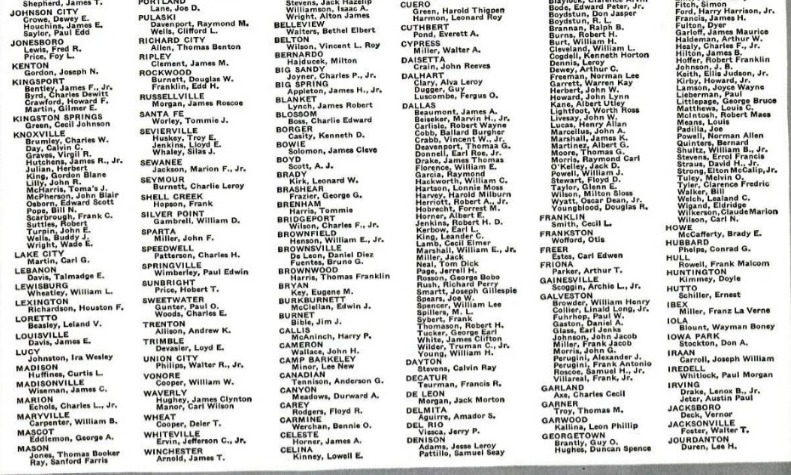

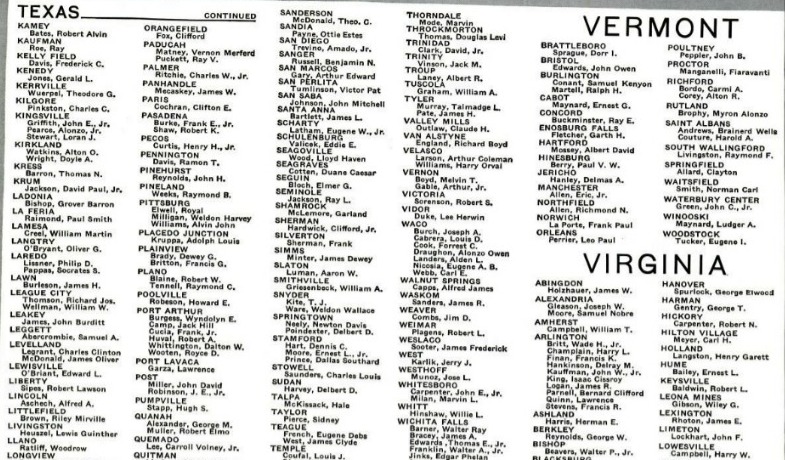

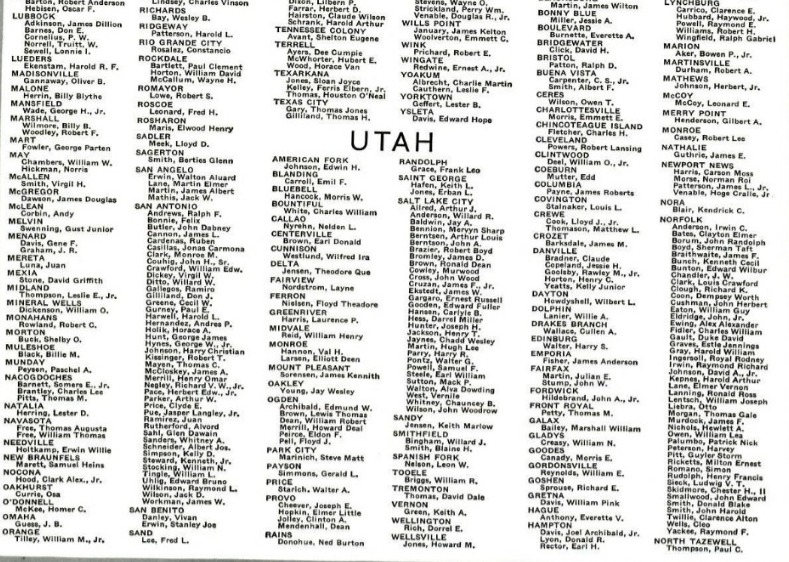

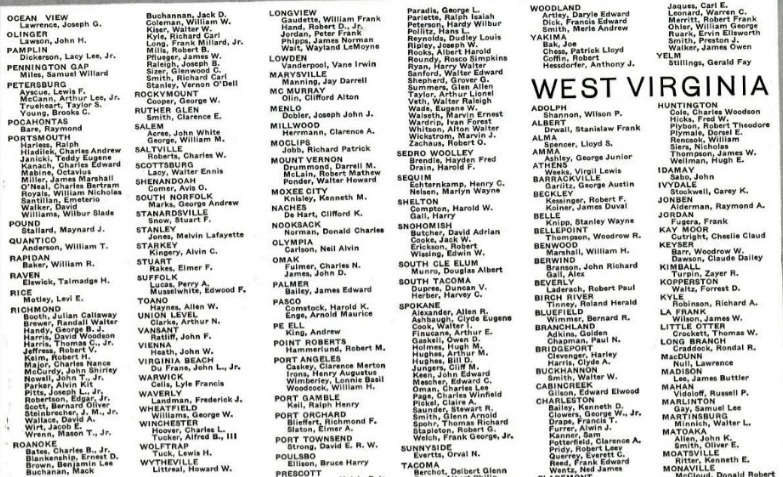

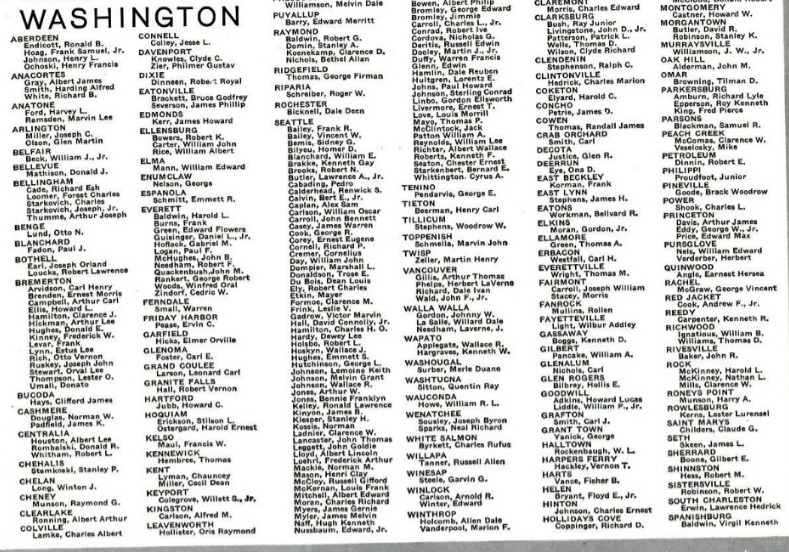

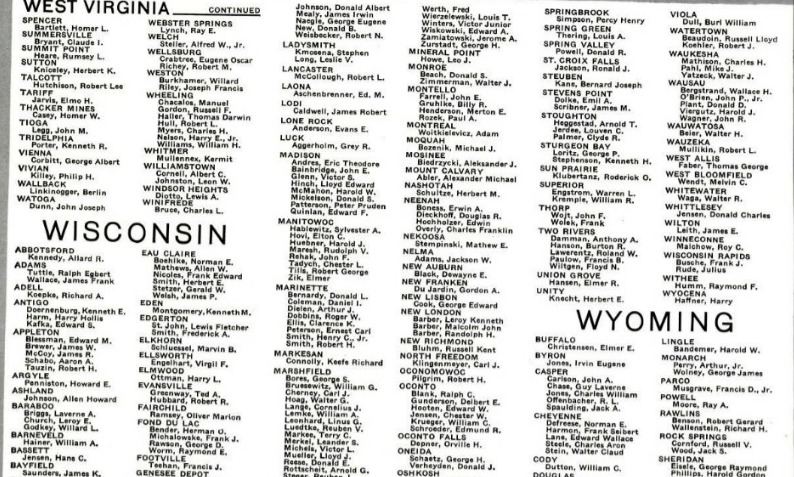

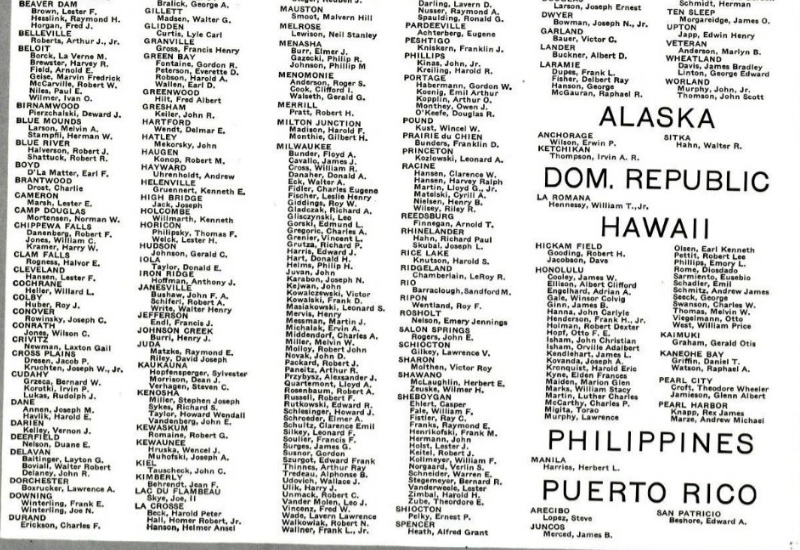

LIFE lists names of servicemen who gave their lives for their country in war’s first 18 months, with next-of-kin addresses

In a field of Tunisian wheat, CH Herbert Ricke conducts funeral service for a U.S. pilot. Friends bow their heads in prayer.

On the next 23 pages, LIFE compiles from official Army and Navy announcements and prints by state and town the names of American soldiers, sailors and Marines who gave their lives for their country during the first 18 months of war. With each name is listed the address of his next of kin – which is not always the last address of the dead man. The list includes only men killed in action with the enemy, those who died of wounds and those who did in enemy prison camps. It does not include men who died of non-combat accidents or disease, either abroad or in the continental United States. Nor does it include men who are reported missing in action.

On the list are 12,987 names. Last week, Washington announced that 15,132 men had been killed in action – 7,528 in the Army, 7,604 in the Navy. The difference between LIFE’s list and the Army-Navy list is that the Army and Navy release casualty figures before they release the names and addresses, which are never publishable until the next of kin have been notified. In addition, a few names were received too late for inclusion on LIFE’s list. Furthermore, the list may have some mistakes because it is often very difficult to identify all the dead after a battle.

As a nation, the U.S. is not accustomed to big war casualties. Not since the Civil War has its manpower been seriously weakened by battle losses. In World War I, in which it was a participant for just 19 months – almost the same length of time as covered by the lists on the following pages – it had a total of 126,000 combat dead. Its full AEF casualty list, including dead, wounded, missing and prisoners, was only 364,000, approximately 8% of the men in its Armed Forces. This compares with 75% casualties for Russia, 73% for France, 65% for Germany, 39% for Italy and 36% for the British Empire.

As of last week, total announced U.S. casualties for World War II, including dead, wounded, missing and prisoners, were 90,860. Comparatively it is a small figure. Great Britain has lost close to 600,000 men, the Russians 5,000,000, the Germans approximately 4,000,000. But the U.S. has been in the war only a year and a half. During most of that time it has been on the defensive, fighting only when necessary, building up its strength. When the great, offensive battles come, its casualties will mount.

It lives in the hearts of those who have received the telegrams from the Adjutant General

That is the list. Those are the boys who have gone over the Big Hill.

Those are the names in the telegrams flashed over the long, sagging wires:

Regret to inform you… your son… killed in action…

Along the crooked stone walls of Connecticut and over the lush valleys of Pennsylvania and down into the sultry cottonlands of Georgia:

And around the rippled lakes of Wisconsin to the cool, blue northland, and in straight lines out over the hazy Dakotas, over Kansas:

Leaping and bounding across the Rockies to the yellow deserts of Arizona, and onward, to the miraculous, green Pacific orchards, where the water pumps chug all day in the sun:

The roll call of the Adjutant General.

Maybe you haven’t got this message yet, maybe you haven’t heard from the Adjutant General: well, you are just lucky – you can’t know what it is to have your boy go over the Big Hill:

You can’t know what it is to open the door of the garage and see the car he helped out buy – or to sit on the bed in his old room and see the picture of his girl there on the dresser, and his empty shoes in the closet – or to wander down into the cellar, as if looking for him, and see the holes he drilled in the cellar stairs when he was just a kid, and you bawled him out for it. You can’t know any of this.

But maybe it would be a good idea to try to imagine it. For the people who get these telegrams ask a question: and this question is one that everybody in America must answer, and this question is, WHY?

What is it that called them over the Big Hill? What is the purpose?

When you talk about purpose, though, you have to make a distinction. It doesn’t make any sense to mix up the purposes of the dead with the purposes of the living. The boys didn’t go over the Big Hill in a philosophical mood. They didn’t say, This or that is at stake, so now I am going to die for it. That isn’t the way it happens at all.

It happens unexpectedly, when he is doing something he learned at Fort Benning, and learned all over again on maneuvers in Alabama, over and over and over; and he is swearing at the machine gun, which has jammed, or at the heat, or at the cold, and he wants to tear the guts out of that damned bastard in the pillbox across the gully – and then it happens, suddenly, so that even if he gave a hoot in hell about the purpose, he wouldn’t have time to think about it, let alone say what it is.

And if there was even an instant when he had a chance to think, his thoughts would have been so simply that we could understand them, let alone write them down:

For in that instant, he would see his home, and he would see Mom bending over the stove and hear the kid brother in the yard; he would see his whole town and the movie theater and the baseball diamond and the cars, and hear the voices of the girls, and remember the first girl he kissed, and even more the last one; he would all in an instant relive that life and know that it was a good life, and if they wanted to call that life “freedom,” that would be Okay with him:

But it doesn’t matter what he himself would call that life, or how he would define the purpose, because he is not a part of it anymore, it goes on without him, and whatever he was in that community is lost, except the monument with his name on it, and the memory of him and what people do in the name of his memory.

And yet this is not true of us who are living. We still have the town and the movie theater and the baseball diamond, and we have his memory. So, it matters a great deal what we say the purpose is, it makes all the difference in the world; indeed, it is for us to decide whether he died for the fulfilment of a purpose, like the boys of the American Revolution, or whether he died for the fulfilment of practically nothing, like the boys of World War I. The dead boys will become what we make them.

So, we who are living must know our purpose and pursue it.

And the chief fact that we must face in pursuing it is that the U.S. has always been different from other countries. And the chief decision we have to make is whether we intend to maintain this difference, or to abolish it.

The U.S. differs from other countries because it was founded for the purpose of achieving a particular and definite goal in the evolution of man. For until the U.S. was established, men found their highest purposes in the Church, in the arts, in institutions of various kinds, and they expected their nations to support these purposes, but they never conceived of a nation having such a special purpose of its own:

This was the new and unique idea introduced by the U.S. into the family of nations – a purpose stated in the very beginning, and stated over and over again by the leaders of our people;

And this purpose for which our nation was founded, and in which our nation has persisted, is TO MAKE MEN FREE;

Yes, that is what the Declaration of Independence says, that is what they signed 167 years ago, that all men are created free and equal – not just our own people, but all people:

And that is what Thomas Jefferson said:

Nor are we acting for ourselves alone, but for the whole human race.

And, later, Andrew Jackson said the same thing – he said:

Providence… has chosen you as the guardians of freedom to preserve it for the benefit of the human race.

And, still later, Abraham Lincoln called the cause of freedom in the U.S. “the last best hope of earth;” and when Mr. Lincoln spoke about the boys who died at Gettysburg, he summed up the destiny of the U.S. in words that every American knows almost by heart: He said:

It is for us, the living… to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Yes, this is the dream we have always had, that in founding the United States of America we were summoning all the people of the earth into the green pastures of liberty.

And only in the last 25 years, only since the World War, have we abandoned this dream; only in our generation have we said, To hell with this purpose. Even the boys who are listed here might have said that. We taught them to.

And we must decide now whether that is the course to follow; whether to abandon the dream and try to be like other nations.

Or to rekindle within ourselves the great purpose of liberty, the great light that shone behind the Big Hill for all the American boys who have gone over it except these particular boys of ours.

And surely our only answer can be, Rekindle the light! For otherwise we shall be sending them over the Big Hill into darkness.

For there is such a thing as freedom in the world, and there is such a thing as slavery; and to abandon now the American dream is to say that we don’t care whether we are surrounded by slavery, or not;

But our inescapable purpose is to strengthen freedom; to strengthen it first at home, where the boys see it so clearly – and to push it also outward, to other nations, farther and always farther, around the smoking and tumultuous earth.

This is the answer to the question that is raised by the people who get these telegrams from the Adjutant General.

And these people know this answer, they know what Lincoln meant, they know what our purpose is, they cannot doubt it:

For these telegrams aren’t really written on paper at all, but on the hearts of the people who get them;

They are written on the hearts of the mothers and fathers, the sisters, the brothers, the wives, the sweethearts – the lonely people – of the U.S.:

And when these people open the telegrams, it becomes perfectly clear, in an instant, that the Adjutant General doesn’t really send them anyway – that he only signs them;

That God sends them, about His own boys, for His own reasons, and will continue to send them and will give us no respire and no rest until we have discovered His reasons and done a job for the reasons we have discovered.

The great light of America is rekindled in the breasts of those who have clutched these telegrams in their fists in that terrible moment when they come.

This strange form of Broadway jargon is coloring the speech of our Armed Forces

By George Frazier

…

Americans maul and murder each other as Hitler wins a battle in the nation’s most explosive city

…

U.S. Navy Department (July 5, 1943)

South Pacific.

On July 4‑5, during the night, a number of U.S. surface units bombarded Japanese installations at Vila, Kolombangara Island, and Bairoko in Kula Gulf, New Georgia Island. A number of fires were started.

On July 5, in the morning, a formation of Army Hudson (Lockheed A‑29) light bombers attacked Rekata Bay, Santa Isabel Island.

The following information has been announced in the South and Southwest Pacific:

On July 3, it is reported that Vura Village on Vangunu Island in the Wickham Anchorage area was captured by U.S. forces.

On July 4, in the early afternoon, U.S. planes intercepted and attacked an enemy formation of 18 bombers and 20 Zero fighters over Rendova Island, New Georgia Group. Five enemy bombers and four Zeros were shot down. No U.S. losses were sustained.

South Pacific.

Brief reports from the South Pacific indicate that a naval battle is in progress in Kula Gulf, north of New Georgia Island.

No details of the action have been received.

U.S. Navy Department (July 6, 1943)

South Pacific.

On the night of July 4‑5, the U.S. destroyer STRONG (DD-467) was torpedoed and sunk while engaged in the bombardment of Japanese positions on New Georgia Island. The next of kin of the casualties aboard the STRONG will be notified as soon as possible.

On the evening of July 5, Army Liberator (Consolidated B‑24) heavy bombers attacked Japanese installations on Ballale Island, Shortland Island Area. Five fires were started. About 12 Zero fighters attempted to intercept but were driven off. No U.S. losses were sustained.

On July 6, in the early morning, a U.S. surface task force engaged Japanese surface units in Kula Gulf off New Georgia Island. (Previously reported in Navy Department Communiqué No. 434). Sufficient details have not been received to give the results of this engagement, but it is believed that, while some damage was suffered by the U.S. force, considerable damage was inflicted on the enemy.

Völkischer Beobachter (July 6, 1943)

Eigener Bericht des „Völkischen Beobachters“

…

Brooklyn Eagle (July 6, 1943)

U.S. ships damaged in Kula Gulf clash

…