Huge numbers of U.S. fliers reach Britain

By Nat A. Barrows

…

Orders in civilian life and military have same meaning but get different results

By Ruth Millett

…

By Ernie Pyle

Allied HQ, North Africa – (by wireless)

Another friend, whom I’ve mentioned before in these columns, is among the missing. He, we know almost definitely, is a prisoner.

He is Capt. Tony Lumpkin, of Mexico, Missouri. Tony was headquarters commandant of a certain outfit – a headquarters commandant being a sort of militarized hotel manager.

Just before he disappeared, Tony got to going by the nickname of “Noah” Lumpkin, because he always seemed to pick out such a miserably wet place for a command post. On their last move before he was captured, the commanding general – a swell guy with a sense of humor – called Capt. Lumpkin over, stood with him outside a tent looking out over the watery landscape, and congratulated him on locating them in the center of such a beautiful lake.

Tony wanted to do some shooting

Tony Lumpkin needn’t have been captured at all if he had been content to stick to his comparatively safe “hotel managing.” But he wanted to get a crack at the Jerries himself. He is an expert gunner, and he finally talked the commander into letting him take five men and a small gun on wheels and go out to see what he could pick off.

The first day they got one German truck plus something that turned out later to be a camel, although it looked like a truck at the distance they were firing from. The second day they moved farther into the mountains to get into a better shooting position, but bagged nothing. On the third day they went even farther into the hills, hunting a perfect spot for firing.

Capt. Lumpkin used to share a tent with Maj. Chuck Miller of Detroit, and with their assistant, Cpl. William Nikolin of Indianapolis, both of whom I’ve written about before. They formed an intimate little family.

That third night Maj. Miller came in late. He was astonished, and a little bit concerned, to see Tony’s cot empty. When he woke up next morning there was still no Tony.

He knew something had happened. He went to the general and got permission to start out with a squad of his own military police and hunt for his lost companion.

Tony really gets lost

They covered all the ground Tony had covered, and finally, by studying the terrain and talking with others who had been nearby, and interviewing German prisoners, they pieced together what had happened. The hill that Capt. Lumpkin had been trying to get to had been simply lousy with German machine-gunners. The Germans saw him all the time. They sent out a party that worked behind and surrounded him. A German who was captured later said that a captain with a Tommy gun killed one German and wounded another before being taken. That is all we will know until Tony comes back to us.

There isn’t grief in the little Lumpkin-Miller-Nikolin family, but there is a terrible vacancy.

Maj. Miller says:

We were a perfect team. Tony was slow and easygoing, and I’m big and lose my temper too quickly. We balanced each other. I’d keep him pepped up and he’d calm me down. We sure miss him, don’t we, Nicky?

The two who remain, the officer and the corporal, seem drawn even close together than before. When there are guests, Nicky is called in to be part of the company. Nicky waits on the 6’4” major as though he were a baby, and the major treats Nicky with an endearing roughness.

They’d give a lot to have him back

Maj. Miller went on:

Nicky always woke us up every morning by bringing in hot tea. Then the damn intellectual would ruin the day for me by sitting down while we drank the tea and starting an argument along the line of who was the greater writer, Tolstoy or Anatole France. That kind of stuff throws me.

Tony would argue with him, and relieve me of the horror of such a subject at such an hour. But now that Tony’s gone, I have to bear the load all by myself. It’s awful.

And Nicky stands and grins while the major talks.

Our conversation drifted off onto other things, and a long time afterwards, out of a clear sky, Maj. Miller said:

Damn it, I’d give a month’s pay – no, I’d give six months’ pay – no, I’d give a year’s pay if only old Tony were back.

And Nicky would gladly do the same.

Mills readjust schedules to meet ‘various changes in strategy’

…

Those accepted to be given ratings of TSgts.; educational and physical requirements may be waived

…

doesn’t it make sense for to take old grandmoms to tailor stuff? They make it with love.

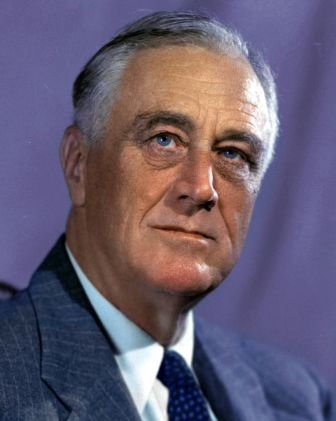

It gives me great pleasure to welcome to the White House you who have served so splendidly at the epoch-making United Nations Conference on Food and Agriculture.

I use that word “epoch-making” advisedly. The Conference could not have failed to be significant, because it was the first United Nations Conference; but it has succeeded even beyond our hopes. It is truly epoch-making because, in reaching unanimity upon complex and difficult problems, you have demonstrated beyond question that the United Nations really are united – not only for the prosecution of the war, but for the solution of the many and difficult problems of peace. This Conference has been a living demonstration of the methods by which the conversations of nations of like mind, contemplated by Article VII of the Mutual Aid Agreement, can and will give practical application to the principles of the Atlantic Charter.

You have been dealing with agriculture, the most basic of all human activities; and with food, the most basic of all human needs. Twice as many people are employed in work on food and agriculture as in work in all the other fields of human activity put together. And all people have, in the literal sense of the word, a vital interest in food.

That a child or an adult should get the nourishment necessary for full health is too important a thing to be left to mere chance.

You have recognized that society must accept this responsibility. As you stated in your declaration:

The primary responsibility lies with each nation for seeing that its own people have the food needed for health and life; steps to this end are for national determination. But each nation can fully achieve its goal only if all work together.

And on behalf of the United States, I gladly accept this declaration.

You have gone beyond the general recognition of principles, to deal in specific terms with specific tasks and specific projects.

You have examined the needs of all countries for food and other agricultural products, both as they will exist, or rather, to put it this way, as they will exist in the short-run period of recovery from the devastation of war – the few years when the fighting stops – and as they will exist over the longer run, when our efforts can be fully devoted to expanding the production of food, so that it will be adequate for health the world over, and all through the years to come.

You have surveyed with courage and with realism the magnitude of these problems, and you have reached unanimous agreement that they can, and must – and will – be solved.

It is true that no nation has ever had enough food to feed all of the people as we now know that human beings should be fed. But neither have nations representing over 80% of the world’s two billion inhabitants ever before been joined together to achieve such an aim. Never before have they set out to bend their united efforts to the development of the world’s resources so that all men might seek to attain the food they need.

For the short run, you have pointed out steps that have to be taken, both in increasing supplies and in maintaining the economy of use and coordination of distribution.

In considering our long-range problems, you have surveyed our knowledge of the inadequacy in the quantity and the quality of the diet of peoples in all lands. You have pooled our knowledge of the means of expanding our output, of increasing our agricultural efficiency in every nation, and of adjusting agricultural production to consumption needs. In the fields of both production and consumption you have recognized the need for the better utilization of the knowledge we now have, and for extending still further the boundaries of our knowledge through education and research.

You have called upon your governments individually and collectively to enlarge and improve their activities in these fields.

For the perfection and the rapid execution of these plans, you have recommended the creation of a permanent United Nations organization, and for that I specially thank you. To facilitate and hasten the creation of that organization, and to carry on the work that you have begun until it is permanently set on its feet, you have established an Interim Commission. The government of the United States is honored that you have asked that the Interim Commission have its seat in Washington, and will be glad to take the preliminary action for the establishment of that Commission which you have entrusted to it.

Finally, you have expressed your deep conviction that our goal in this field cannot be attained without forward action in other fields as well. Increased food production must be accompanied by increased industrial production, and by increased purchasing power. There must be measures for dealing with trade barriers, international exchange stability, and international investment. The better use of natural and human resources must be assured to improve the living standard; and, may I add, the better use of these resources without exploitation on the part of any Nation. Many of these questions lie outside of the scope of the work that you have undertaken, but their solution is none the less essential to its success. They require, and I think they shall receive, our united attention.

In the political field, these relationships are equally important. And they work both ways. A sound world agricultural program will depend upon world political security, while that security will in turn be greatly strengthened if each country can be assured of the food it needs. Freedom from want and freedom from fear go hand in hand.

And so I think that our ultimate objective can be simply stated: It is to build for ourselves, meaning for all men everywhere, a world in which each individual human being shall have the opportunity to live out his life in peace; to work productively, earning at least enough for his actual needs and those of his family; to associate with the friends of his choice; to think and worship freely; and to die secure in the knowledge that his children, and their children, shall have the same opportunities.

That objective, as men know from long and bitter experience, will not be easy to achieve. But you and I know, also, that throughout history there has been no more worth-while, no more inspiring challenge.

That challenge will be met.

You have demonstrated beyond question that free peoples all over the world can agree upon a common course of action, and upon common machinery for action. You have brought new hope to the world that, through the establishment of orderly international procedures for the solution of international problems, there will be attained freedom from want and freedom from fear. The United Nations are united in the war against fear and want, as solidly and effectively as they are united on the battlefront in this world war against aggression.

And we are winning that war by action and by unity.

U.S. Navy Department (June 8, 1943)

South Pacific.

On June 7, during the morning approximately 40 or 50 Japanese Zeros and torpedo bombers were attacked by U.S. fighter planes in the vicinity of the Russell Islands. Nineteen Zeros were shot down and six damaged. U.S. losses were seven planes, but three of the pilots were saved.

North Pacific.

On June 7, an additional 8 Japanese were killed on Attu Island. Eleven more of the enemy killed themselves with grenades after being surrounded by U.S. Army troops in Chichagof Valley. The total known enemy dead as of June 7 is 1,826.

The Pittsburgh Press (June 8, 1943)

3-way smash at Europe hinted

By Harrison Salisbury, United Press staff writer

…

U.S. loses 7 aircraft in Solomons air battle

…