New attacks on Tokyo promised as Army tells of Doolittle Raid

Hornet revealed as ‘Shangri-La’ used by bombers

By Sandor S. Klein, United Press staff writer

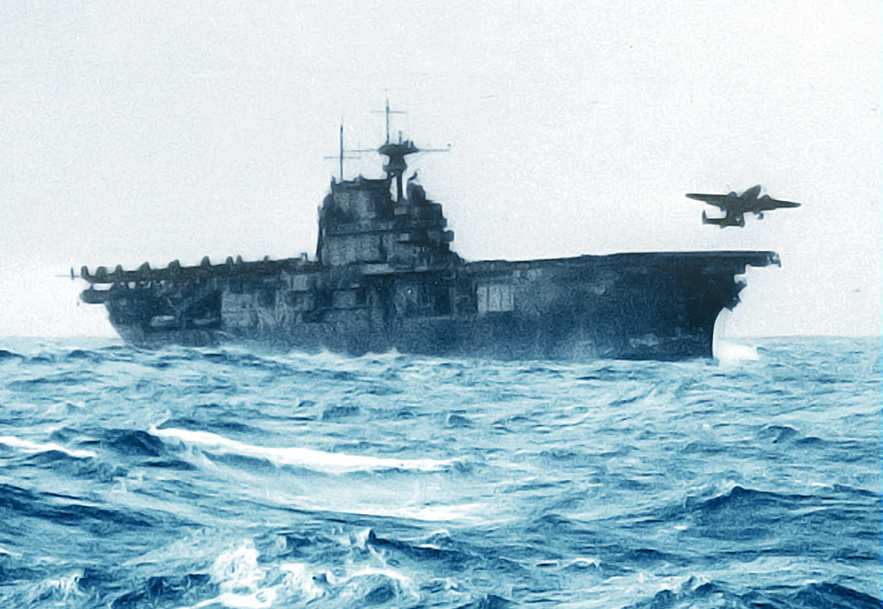

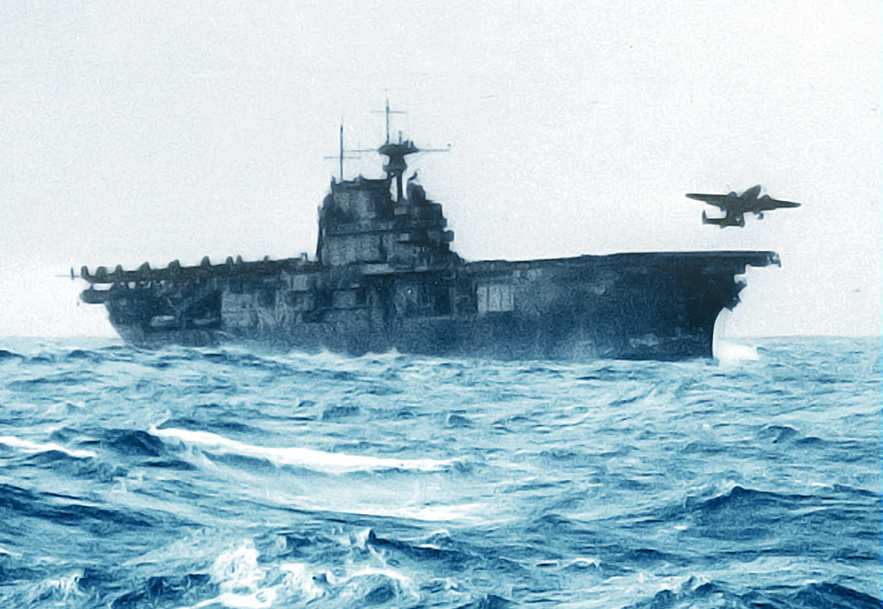

First off for Tokyo, Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle “bounces” his B-25 bomber off the U.S. aircraft carrier Hornet, as the ship rides in heavy seas, to lead his flight of bombers on the April 1942 raid on Tokyo. The other Billy Mitchell bombers can be seen on the aft flight deck of the Hornet.

Washington –

Japan will be bombed again and again.

This warning was held out to the Japs by the War Department in making public for the first time the official story of the bombing of Tokyo by Maj. Gen. James H. Doolittle’s 80 handpicked raiders.

It was a story of heroism and success; of hardships and hard luck at the beginning and end.

Aside from officially confirming that the “Shangri-La” from which the 16 Army medium bombers were launched was the aircraft carrier Hornet, the most interesting part of the long-awaited account of the raid was what happened to its participants and their planes after they had completed their mission over Japan.

15 of planes wrecked

The story with the happy climax came to a sour ending. The planes were supposed to have landed on airfields in Free China when their job of destruction was done. But this is what happened:

All but one of the 16 planes were wrecked in forced or crash landings in China or off the Chinese coast. The exception was a plane that landed in Russian Siberia.

Of the 80 participants, eight are prisoners or presumed to be prisoners of the Japs. One was killed after a parachute landing in mountainous Chinese terrain. Two others are missing, with no clue to their fate. Five are interned in Russia. The remaining 64 gained the safety of unoccupied China. Seven of these were injured.

And there is an anti-climax to the story. Of the 64 who got away, nine were subsequently killed or are missing in action and one is a prisoner of Germany.

Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., now U.S. commander in the South Pacific, commanded the task force that carried the planes to within 800 miles of Tokyo. Adm. Halsey had planned to carry the fliers to within 400 miles of Japan, but an encounter with an enemy patrol vessel – which was sunk – spoiled that plan.

Accomplish mission

Gen. Doolittle was the first to take off from the Hornet in one of the specially-equipped, twin-engined North American “Mitchell” bombers at 8:20 a.m., on April 18, 1942. Shortly, all 16 were in the air headed toward Tokyo after takeoffs in a heavy sea that sent waves over the carrier’s bow and forced the pilots to time their takeoffs with the upbeat of the flight deck.

The primary objective of the mission – to bomb the Jap mainland – was accomplished “with complete success,” the War Department said. Not a single U.S. plane was lost in Japan proper.

What is more, the War Department assures, Tokyo is due to be hit again. The report said:

If the secrecy [of Shangri-La] could always have been kept from the Japanese – which in the end was impossible – it would naturally have added to the tension with which Japan awaits the attacks that still lie ahead.

Besides its destructive and psychological effects, the War Department emphasized, the raid:

…resulted in freezing, within Japan, enemy airplanes and other forces which might have been used in offensive operations elsewhere.

This was one of the deciding factors in the decision to keep details of the American operations a secret for more than a year. This was why President Roosevelt referred to the raid base as “Shangri-La,” a mythical place.

Months ago, the Japs claimed to know the secret of Shangri-La. They named the Hornet. They had already had their revenge on that gallant ship, sending her to the bottom in the Battle of Santa Cruz on Oct. 26, 1942.

Had fate been more kindly, the aftermath of the raid might have been a happier one. But almost from the start, hard luck intervened. After evading two enemy patrol vessels, the Hornet ran into a third. This was 800 miles off Tokyo. The takeoff had been planned at a point about 400 miles from the enemy capital. It was to have been just before dark, so that the attack could be carried out at night and the planes could continue on to land at specified Chinese airfields in the morning.

Start ahead of time

But fear that the third patrol vessel, which was sunk, might have radioed a warning caused the immediate launching of the planes – 10 hours ahead of schedule.

What happened over Japan has already been told by Gen. Doolittle himself. The planes flew in so low – 15 or 20 feet above sea level – that they were almost skimming the wave tops.

There was anti-aircraft fire, some heavy, but no real damage was done. And there were at least 30 pursuit planes aloft but they could not lay a finger on the hedge-hopping Americans.

Upon leaving Japan, the scattered planes ran into a storm. The official account said:

Their already-depleted gasoline reserves were drained further as they bucked the winds. Darkness was coming on and the unfamiliar terrain added to the difficulties. There were no light beacons or landing flares. Unable to go farther, there in the darkness, 6,000-10,000 feet above a strange land, the great majority of the men bailed out.

Most of the men landed in unoccupied China and succeeded in reaching Chungking, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s capital. But some less fortunate landed in occupied China. This led to the capture of eight. Others managed to make their way out of enemy territory with the aid of friendly Chinese who had several of them for long periods.

The only known dead was Cpl. Leland D. Faktor, of Plymouth, Iowa, who made a getaway in his parachute but may have been killed by a fall after landing in mountainous territory. His body was found later.

Lands in Siberia

The only plane to make a safe landing was piloted by Capt. (now Maj.) Edward J. York, of San Antonio, Texas. After bombing Tokyo, his plane had so little gas left, he headed for Siberia and landed 40 miles north of Vladivostok. The ship and crew were interned by the Russians.

One of the planes, piloted by Lt. Ted W. Lawson, of Los Angeles, crashed in the China Sea within three miles of Jap forces. Cpl. David J. Thatcher, of Billings, Montana, was cited for his initiative and courage in tending his companions.

The War Department said that the preoccupation in bringing American fliers to safety was a principal reason why no detailed statement was issued after the raid.

The idea of the raid on Tokyo was conceived first in January 1942, when the desire for revenge on the Japs for the Pearl Harbor attack was barely a month old. Whose idea it was, the War Department did not reveal, but Gen. Doolittle, who was then a lieutenant colonel, took charge of the preparations.

Selects crews

He personally selected the men who were to accompany him. They were all volunteers. There followed months of intensive, specialized training. Much of it was at Eglin Field, Florida.

Using white lines on the field to measure, the fliers concentrated on taking off in the shortest possible distance, because the flight deck of the Hornet-type carrier is approximately 800 feet long.

In order to preserve the secret of the Norden bombsight should any of the B-25s be forced down in Japan, the Norden sight was replaced with a simple 20¢ sight devised by Capt. (now Maj.) C. R. Greening, of Hoquiam, Washington.