Ace Negro stars aid U.S. hour

Bill Robinson and screen’s Hattie top guests

By Si Steinhauser

America’s great Negro stars will contribute to tonight’s Treasury Hour on KQV at 8 o’clock. Bill Robinson, Hattie McDaniel, one of the stars of “Gone with the Wind;” Fats Waller, ace pianist-maestro, and the Deep River Boys are included.

Quartermaster General Edmund Gregory of the Army will speak.

Other entertainers will include Franchot Tone as MC, Zorina, Victor Moore and Billy Gaxton of the musical show “Louisiana Purchase;” Marcel Hubert, cellist and Hildegarde, nightclub singer.

![]()

The Missing Heirs program celebrates its third year of continuous broadcasting tomorrow.

![]()

The Cavalcade of America will repeat its Christmas presentation of “Green Pastures” on December 22.

![]()

Rep. Oscar Youngdahl will occupy tonight’s Public Affairs period (WJAS, 10:15) with a talk on “National Unity.”

![]()

Henry C. Wolfe will tell what he saw in the Philippines when he was there as a reporter and screen star Bob Montgomery, now a naval aide in London, will report about England on tonight’s We, the People broadcast.

![]()

Some time ago this column said that NBC would split up its subsidiaries among its present brass hats. A group headed by Alfred H. Morton, television chief, has just taken over the NBC Artists Bureau and will set up headquarters at NBC’s old address, 711 Fifth Avenue, New York City.

![]()

NBC executives from all parts of the nation were called to New York to discuss separating the Red and Blue Networks. Then the Japs started things and the conference broke up, the big shots scattering to their respective stations.

![]()

Every office window in Radio City has a new opaque blackout curtain. Studios have no windows.

![]()

Amos ‘n’ Andy are starting movie shorts called “Unusual Occupations.” Three little words for those shorts: better be good.

![]()

In two and a half years, 110 characters have supported Elizabeth Reller and Alan Bunce, stars of “Young Dr. Malone.”

![]()

Edna May Oliver will be on hand to welcome John Barrymore back to the Rudy Vallee Program, Thursday night.

![]()

Sammy Kaye’s band has a booking record, engagement having been signed to keep the gang busy to January 1943.

![]()

Ilka Chase, head lady of radio’s Penthouse Party, smart-cracked “Without big weddings, you can’t have little ones.”

![]()

All-time radio stunt: Barbara Weeks announced her own death when she played the part of an elderly woman on her death bed, then doubled as the nurse who pronounced the woman dead.

![]()

Jack Benny has no greater admirer than this scribe but we do wish he would quit talking for the benefit of his intimate friends and leaving his listening audience puzzled. The Tom Harrington he talked about Sunday night is the radio chief of a big New York agency.

Million-dollar cast heard on Bill of Rights program

Cpl. Stewart

NEW YORK (UP) – A lowly Army corporal n one-day leave from camp introduced the president of the United States last night in one of the most unusual radio programs ever heard in this country.

It was the Bill of Rights broadcast which was put on the air from Hollywood and then switched to Washington for an address by President Roosevelt.

One of the features of the broadcast was that acting talent which would cost a million dollars a year at a conservative estimate participated without pay and, in most cases, anonymously. The talent included Cpl. Jimmy Stewart of Moffet Field Air Station, who hurried away from the studio after the broadcast to catch a train so he wouldn’t overstay his leave.

Proposed by MacLeish

The Bill of Rights broadcast started in the mind of Archibald MacLeish, Librarian of Congress and a well-known poet, who took the idea to President Roosevelt and obtained his approval. The Office of Civilian Defense was instructed to prepare a broadcast and Mr. Roosevelt agreed to participate with a brief address.

Radio time was arranged on all networks and Norman Corwin, a radio scriptwriter, prepared all the material except the president’s speech. Mr. Corwin went to the West Coast to supervise the broadcast.

W. B. Lewis, vice president of the Columbia Broadcasting System and now on loan to the Office of Facts and Figures in Washington, was placed in charge of obtaining talent. He lined up the following “million-dollar” cast: Lionel Barrymore, Edward Arnold, Walter Brennan, Bob Burns, Walter Huston, Edward G. Robinson, Rudy Vallee, Orson Welles, Marjorie Main and Cpl. Stewart.

The actors’ parts were not identified and the listening public could not be certain who was enacting which role until the end of the broadcast.

Studio audience banned

In an attempt to improve the quality of the performance, it also was agreed that there should be no studio audience. Even the executives of the radio networks were not present.

The only persons to witness the show were technicians in the control booths. Several of them were deeply affected and said they almost were in tears at some stages of the show, particularly when Cpl. Stewart gave his description of Washington.

Barrymore opened the broadcast and then turned it over to Cpl. Stewart as narrator. The narrator traced the development of the Bill of Rights and then Cpl. Stewart introduced President Roosevelt.

Hero in Hawaii tells how he shot down 4 Jap bombers as ‘hell broke loose’

HONOLULU, Hawaii (UP) – Lt. George Welch, 22, of Wilmington, Delaware, was credited today with shooting down four Japanese planes December 7, although he was outnumbered 10 to 1.

“All hell broke loose, and before we knew it, the air was full of Japanese planes,” he said. “I picked up the nearest and went after him. I got a good bead, and the next thing I knew, he was going down in flames.

“I looked for another enemy plane, and discovered I was over a pineapple field and nearly out of ammunition, so I went back to the field. About that time, Lt. Kenneth Taylor [of Hominy, Oklahoma] came up. He shot down a bomber too, and was low on ammunition.

Shot through arm

“We loaded up all the rounds we could carry and took off again. Taylor bagged one more, but got shot through the arm and had to come down. I went over Barber’s Point and shot down three more bombers. When I came back to the field, I had three bullet holes in my own ship – one in the propeller, one in the motor and another just back of the pilot’s seat.

“It was a funny feeling. I was plenty excited and I know I was mad because they caught us on Sunday morning, so we went up and fixed them.”

An official recheck disclosed that Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short’s Army forces knocked down 29 raiders, despite the surprise of the first attack, and the Army announced that “the search for other planes believed to have been shot down is still in progress and the possibility exists that even more bombers bearing the emblem of the Rising Sun will be added to the toll.”

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox said in Washington that a total of 41 Japanese planes had been shot down in Hawaii.

A week after Japanese bombs shattered the Sunday morning quiet, the territory was comparatively calm and quiet again. Evacuees return to their homes. Bathers returned to the beaches. Stoicism replaced tense excitement. Liquor sales were forbidden, and clubs were closed over the weekend.

Aliens must have permits to visit friends or relatives, to change their places of abode, to travel from the places of their businesses or occupation, to move from place to place on the island.

There are approximately 110,000 Japanese living on the Hawaiian Islands, many of them American citizens.

As Honolulu began to relax, some of the most amusing incidents which had been lost in the first tense of days of war began to emerge.

A civilian guard, for instance, who had been posted at the entrance to an engine room, held an officer and five men at bay until he was informed – and he wouldn’t take their word for it – that they had been assigned to run the engine.

A little later, he saw a Japanese go behind a lumber pile.

“Come out with your hands up!” he yelled.

Thirty Japanese came out. The civilian thought he was another Sgt. York until he learned that they were aliens who had already been rounded up and had taken refuge behind the lumber from an air raid. They were already under guard.

Flyspecks on a monstrous ocean –

Mowrer: Marines on Wake, Midway still hold out – but how?

By Edgar Ansel Mowrer

WASHINGTON – “The Marines on Wake and Midway Islands are still holding out.”

This is not Guam. Guam was too big for its garrison. Wake and Midway are flyspecks in a monstrous ocean. You never quite understood how the Pan-American pilots could find them at all, especially after dark. But they did.

There on Wake, with a million birds overhead, with the little brown rats running among the scaevola vines that cover the bare sand, the Marines, their machine guns (and field pieces, if they have any) half-buried in the sand, on the shore are holding a section of the outer defense screen of Pearl Harbor.

Holdout boon to Hawaii

Every day they can hold is a boon to Hawaii and to Uncle Sam. For, if they have any airplanes, every Japanese ship or bomber that strikes at Midway or Oahu further east, takes a long chance on being attacked from the rear.

Wake might have been a strong position, had defense labor been started in time. Last September it had hardly begun. In November a dredge, towed all the way from Seattle, was churning up the lagoon; all sorts of concrete foundations had been laid, and workmen were busy.

These workmen were better paid than most newspaper correspondents. But at that, it was hard to find people to go to Wake Island. And being American, despite entertainment of various sorts, these workmen were always giving up and returning home to the USA. For Wake is the loneliest spot in the world, and few descendants of the Pioneers can stand loneliness.

No grass, lots of sand

Imagine a sand crescent like the thumb and first finger of a hand, a lagoon in the center and a coral reef all around. A few low trees of the rare varieties that will grow in pure sand in the tropics. Sand dunes hardly over 10 feet high at the most. No grass, but the sand half-covered by scaevola vines with big leaves.

High over the island, unless they have been frightened away by the bombs and the firing, tens of thousands of sooty terns, handsome black and white birds with voices like a bandsaw going through an oak knot, turn and wheel day and night; when some are tired, more rise from the ground and take their places.

Among the sooty terns are others, slightly smaller, pure white, with tiny black eyes, a black pointed beak and dainty black feet; fairy terns or love birds. They used to sit over the tennis court all day long in pairs and kiss, or drop onto the shoulder of the onlooker.

Countless little brown rats

Under the scaevola leaves, more timid than the birds but bold for all that, are the countless little brown rats, the myriad descendants of some that came ashore in a derelict ship long ago, and prospered. Presumably the birds live on fish and the rats live on the eggs and young birds, though the latter show no fear of them. There is nothing else to eat and the rats often used to come indoors in broad daylight and run under your feet.

In the center was the charming hotel of Pan American Airlines and behind it the workmen’s dormitories, the power plant, and all the rest. Presumably nothing is left of them now. I can see the Marines flat on their bellies on the beaches, tin hats discarded as too hot, machine guns firing until red hot, gasping for air and water. (Have the Japanese destroyed the fresh water supply and are they digging for brackish salty stuff sulphurous with the rotted eggs of the million birds?)

How are planes concealed?

Where are the American airplanes – if any? How are they concealed? For surely the Japanese have mastery of the air most of the time. How are the Japanese trying to land? From ships in small boats, from the air by parachute, on the American airfield itself? Our Navy has not told us. It has only said, “The Marines are holding out.” The workmen must be running the supply services, they, too, half hidden in vague caves in the dunes in the half-destroyed foundations of buildings under the low trees.

Can relief come by air or by ship? And if not, can they hold out long enough, there is the loneliness of Wake Island, well over 2,000 miles from Honolulu, but less than 600 miles from the nearest Japanese base?

The United Press pointed out that the question of reinforcing Wake and Midway was an obvious military secret, but said naval sources hinted privately that “you wouldn’t lose if you bet that no chances are being passed by for lifting the sieges.”

Chairman Tom Connally, D-Texas, of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, said, “I hope the garrisons at Wake and Midway can be reinforced. The defenders of those islands have shown high courage and lofty patriotism.”

And why, why was not the work of transforming Wake, Howland, Jarvis, Canton and other tiny islands of the outer defense screen of Pearl Harbor, begun in time?

British face back-to-wall fight at Singapore base

London residents asking many questions regarding sudden successes of Jap attacks in Pacific

By William H. Stoneman

LONDON – Having lost naval superiority upon which they had depended for the defense of Malaya, the British forces around Singapore are now confronted by the prospect of a desperate back-to-the-wall defense of that all-important citadel.

The defense of Hong Kong, Britain’s more advanced but less important naval base, is now so difficult that it seems virtually impossible.

Desperate efforts will doubtlessly be made to defend Singapore since its loss would upset the whole strategic position of the Allies in the Western Pacific and would force them definitely to assume a defensive role in that area. It can be assumed that reinforcements will be rushed to that area by sea and air and that the base itself will be in a position to hold out for a long time.

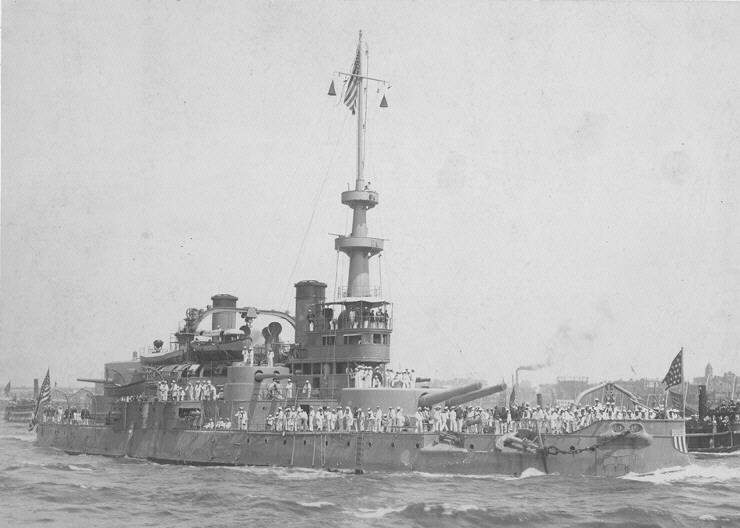

The advance of Japanese troops in northern Malaya, their seizure of airdromes and destruction of Great Britain’s two great capital ships, HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, will expose Singapore to violent attacks from land and air and will greatly limit its activity.

A great many questions are being asked by ordinary British citizens about the manner in which the Japanese were allowed to gain possession of so many strategically vital points with such rapidity.

They want to know why two great battleships put to sea without fighter protection and why the important air base of Kota Bharu was not defended by heavy forces protected by fighters and anti-aircraft guns. They are particularly puzzled because the commander-in-chief at Malaya is Air Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, a Royal Air Force officer, who could be expected to concern himself with air defense before anything else.

They are also concerned by the story of an American eyewitness of the sinking of the Repulse in which he stated that the British naval commander refused to break the radio silence by calling for air support, even after his ships had been sighted by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft.

All these matters may be expected to be aired in Parliament.

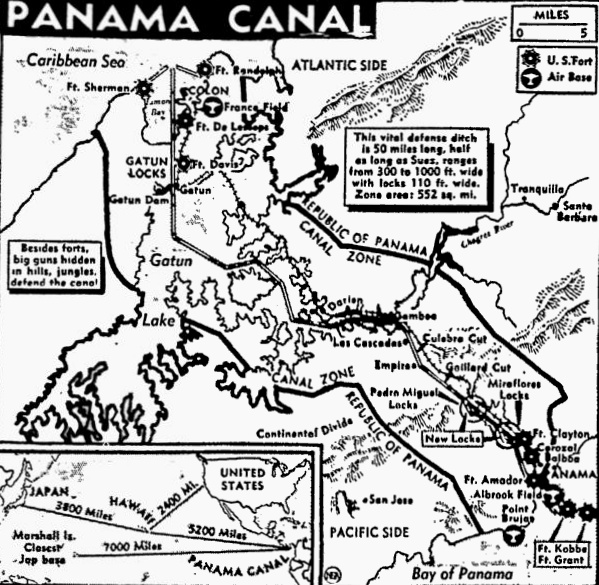

Potential target of enemy saboteurs, warships or bombers is the Panama Canal, the strategic shortcut that saves U.S. warships a 10,000-mile trip around South America. The canal is now one of the most closely-guarded zones in the world.