American Navy’s victory at Midway Isle far more decisive than at first imagined

Casey watches biggest fight of all time

By Robert J. Casey

Ace war reporter Bob Casey seems always to be in the thick of things. Most recently, he has witnessed the Battle of Midway, and here he tells, in the first of a series of articles, the story of that “greatest naval battle of all time.”

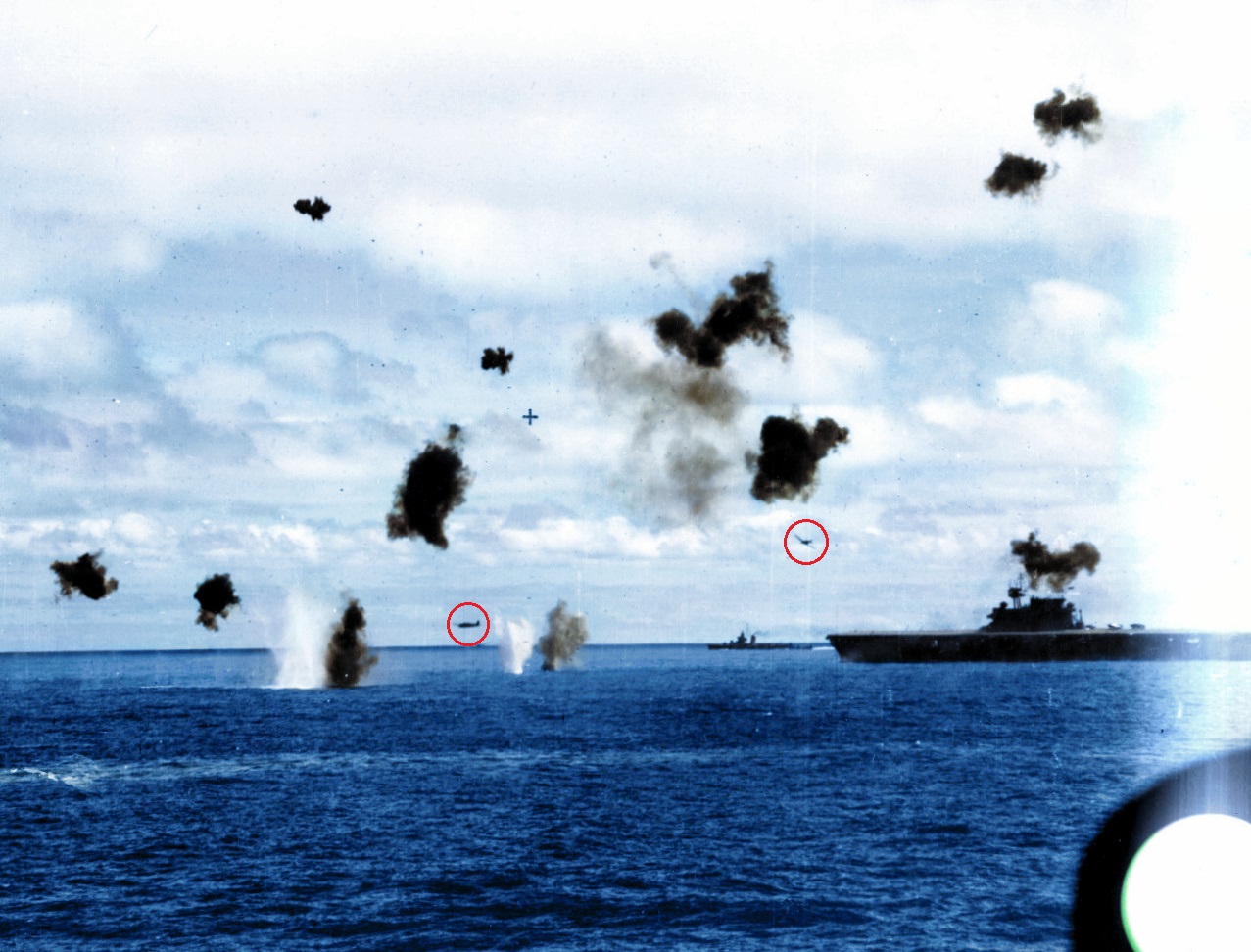

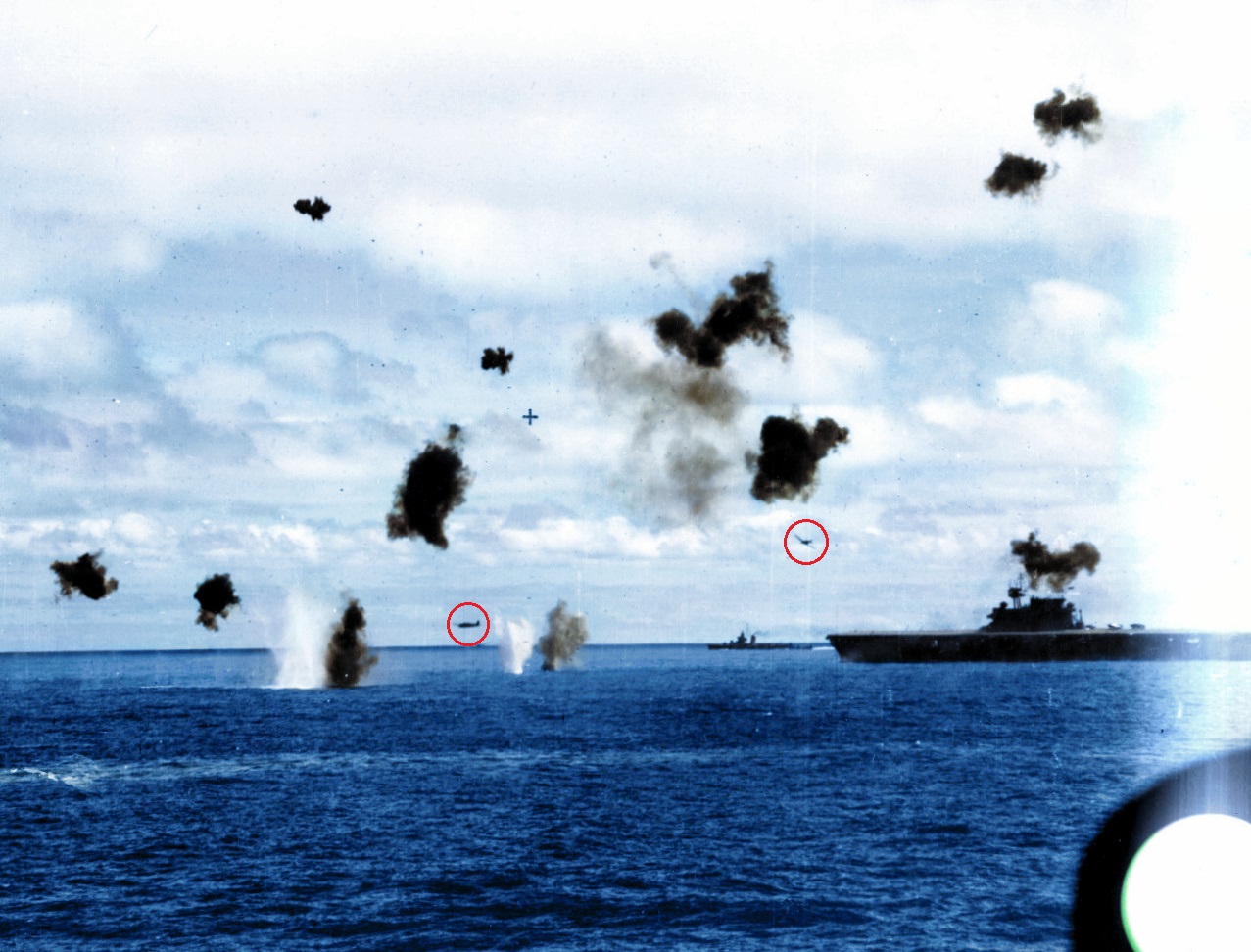

U.S. ‘flattop’ under attack

American anti-aircraft guns etch a pattern of shell bursts in the Pacific sky during the Battle of Midway. An unidentified U.S. aircraft carrier, at right, is being attacked by two Japanese “Zero” fighters (circled). A third Jap plane has just crashed into the sea (at left).

With the Pacific Fleet off Midway Island – (June 4)

A few hours ago, the fleet moved in to snipe a carrier or two out of the overwhelming force that Hirohito, Heaven’s son, was mustering against Midway, Hawaii and points east.

Our force was considerably outnumbered from the beginning, a few hours ago – and it turns out we have fought a major engagement – one of the biggest naval engagements of all time. We have wrecked the best portion of the Japanese fleet and we have diminished the threat of any concentrated attack on Hawaii and the Pacific mainland.

The other night, when definite contact was made, everybody felt that a lot of us would be at the bottom by noon today – that seemed the only certain thing about the whole performance. So it’s no wonder most of us now look at the score in dizzy unbelief.

Obviously, by the time this gets to print, the basic details of Midway will be news to nobody. Probably the record will stand at four carriers, three battleships, four cruisers, four transports, damaged or sunk – with a footnote observing that three of the carriers were definitely on the bottom and the fourth burning and headed down when last seen – that one battleship was left with rudder shot off, endlessly circling, and another set afire.

The conservatism that has governed the issuance of Navy communiqués since the beginning will probably hold down our claims to somewhere around those figures.

But, as a matter of fact, you can write your own ticket about the Japanese losses. Nobody, not even the bomber pilots, can tell you how many Jap ships went to the bottom in the murderous counterattack of our carrier planes – nobody but the Japanese and it will be a long time before they get around to telling.

Attack by individuals

As for the bewildering battle, it will be a long time before anybody gets that straight either.

It was, in the nature of things, an attack by individuals, each of whom saw only his own little sector with his own eyes.

There wasn’t any unusual activity the night when word was received that Navy patrol planes had located the main body of the Jap fleet northwest of Midway. The cribbage game went on as usual. A few nighthawks went on reading stale magazines and most of the ship’s men went to sleep. Tomorrow’s worries would have to stand in line and take their turn.

Descriptions vary

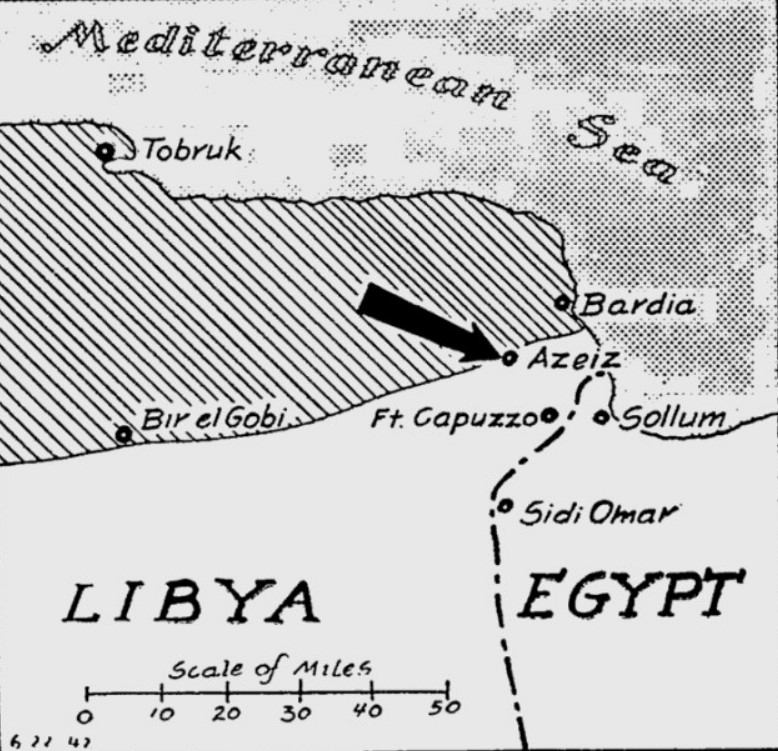

Down from the northwest was coming one of the most powerful armadas ever put to sea in this or any other war. So strong was the force and so cocksure its operators that it moved with no attempt at concealment. It was spotted by patrols and finally by Flying Fortresses based on Midway.

Accurate descriptions of the invasion fleet vary, because no one observer saw all of it at any one time. But it is generally believed that four battleships were in the array, and five carriers (and quite possibly six), 10 cruisers and a train of perhaps 20 transports, tenders and supply ships. Maybe there were only two battleships and two battlecruisers, or two pocket battleships, maybe only four carriers in all, but the figures are reasonably close.

No matter how you rearrange them, this was still one of the strongest naval outfits ever mustered in the Pacific. In the new order of things with aircraft carriers ranking definitely as capital ships, this was as heavy a battle line as has been sent into action since the invention of the dreadnought. And it was obvious, therefore, that the battle would be knockdown-dragout.

Opportunity seized

The Japs had apparently grown tired of the menace of bombers based on Midway and the increasing strength of the Pacific Fleet operating out of Pearl Harbor. It was getting to be evident – particularly after Admiral Yamamoto had gone back on his heels in the Coral Sea – that Japan could not win the war in the Pacific until she took Hawaii.

So, they took this opportunity, when the bulk of the United States Pacific Navy was occupied elsewhere, to move in on Midway.

Some were worried

Some of us were a little concerned when we heard what we were up against – more so than on other occasions when all we had to worry about was land batteries, and high-altitude bombers. We thought that for once, maybe, we were giving away a little too much weight.

By day, we zigzagged in the general direction of nowhere and by night, we listened to destroyers dropping ashcans on things that made noises in the deep – submarines, maybe.

Our chief problem was to keep moving while standing still, apparently. We couldn’t get too far away from Midway if we were to defend it. We couldn’t get too close. Then came the morning the officer came into the wardroom with a message from the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet:

Enemy planes attacking Dutch Harbor.

And somehow everybody aboard ship seemed pleased about it – not that anyone felt cheered about the attack on Dutch Harbor per se, but the Jap appearance in the Aleutians indicated action.

Air alarms sound

The navigator looked up from his waffle.

He said cheerfully:

We ought to be getting into it. Fine opportunity–

We went out after that to attend an air raid alarm and never for a long time thereafter did we get much chance to sit down. The alert lasted a couple of hours while our scout planes ranged around a couple hundred miles tracing down a report that apparently had come from one of the Midway patrols.

But no hostile plane came near us and our roving fighters did not run into any. At noon, one of our naval patrol planes spotted the first of the incoming Jap fleet and reported it a powerful occupation outfit.

At the present rate of speed, they would be within striking distance of Midway at dawn and we, by taking a westerly course, would arrive at the same time within striking distance of their carriers.

Officers imperturbable

One should have thought the conversation of the officers at dinner might take notice of the shortness of man’s days. Instead, the executive officer was orally disturbed over an ancient cartoon that had to do with the population of China – the caption had read somewhat to the effect that if all the Chinese in the world were marched past a given point, they would never finish the parade.

We arose before daybreak, on June 4, to look at a clotted sky with thin, oddly gray moonlight struggling through it. Somebody mentioned that sunrise was late. He was reminded that we were keeping on War Time.

Along about 8:20, “Donald Duck” issued a call to general quarters with an accompanying bee-beep that made it official. As we started for battle stations, we heard the bad news. The Japs had attacked Midway. While we were still upbound on the ladders, the ship heeled into the wind to launching formation and we didn’t have to be told that our bombers would be taking a crack at their carriers. We crossed fingers.

From a perch on the foremast, it was evident that we were starting the ride into battle at the fastest speed this force had worked up yet. From here, the sea appeared crowded with ships – we might not have as heavy a force as the enemy but we were not entirely helpless.

Undetected as yet

We began to have great respect for the handling of this fleet. It got more and more apparent as we drove on toward Midway that we had not been detected. It was a miracle, but there it was. But we were not so strong that we were bragging about it. Half of the Jap Navy was out there ahead of us.

Someone said:

This is the big chance. If we can sink their carriers and battleships – if we can only sink their carriers, the heat is off in the Pacific.

His cheeriness didn’t seem out of order. Of course, the dice might roll the other way. But somehow optimism seemed reasonable.

From the foremast, you could look down on the ack-ack guns beyond the flight deck, all of them with their muzzles in the air as if expecting attack momentarily. Marines manned these guns.

Sky fills with planes

Planes were coming off at short intervals. The sky was filling with them. They circled about in twos and then in quartets and finally were winging under the high clouds in squadrons of 15.

The “Goonies” came to join them – the little albatrosses that always seem to know when trouble is, and are much more skillful at finding us than the Japanese. It began to be evident pretty soon that the carriers were sending up everything they had.

From the signal yard, the flags went up, the flags came down – red, yellow, white, blue; crossed, striped and checkered, a fine sight in the stiff breeze even if their message probably had to do with nothing but course changes. It was all spectacular and thrilling.

During most of the morning, we had been traveling through clouds and rain, but at 9:30, as the last of our planes were turning about overhead for their dash, we came out of the fog bank and into a region of brilliant sky and glowing blue sea. We were now heading due south and the shining planes were slipping over the horizon on our starboard quarter. Everybody in sight was standing motionless as they went out of sight.

The ship’s bell tinkled the hour – as if it made any difference to anybody.

Tense hours of waiting

There followed the usual tense hours of waiting – waiting for our planes, waiting for theirs, nobody was certain which. News came from somewhere that local garrison planes were beating off the Midway attack, that our planes had discovered another force south of the one throwing the planes at the island and had dropped a clunk on a carrier.

The air was filled with alerts, sometimes ours, sometimes relayed to us from other ships. They signified nothing but were sometimes disconcerting.

About 11:30, some fighter planes, presumably part of our protectors patrol, began to come in, tumbling down our skyline like a swarm of mayflies. We began making zigzag patterns all over the sea again.

At noon, somebody brought some sandwiches to the charthouse, and there, a couple of officers and visitors, who had gathered about the messboy, heard the first word of the troubles that had fallen upon the Japs.

Run low on gas

Our fliers, sometime in locating the enemy, had found themselves low on gas. One officer discussed the feasibility of withdrawing from the attack to refuel. But he added that he didn’t think much of the idea.

He said:

There are four carriers here. And they haven’t any air cover. Not air cover at all.

And the reply of the task force commander was something even Japanese competition couldn’t jam off the radio:

Attack immediately.

Conversation fills air

The air by now was filled with scraps of the conversation of our pilots talking to one another on the interplane radio. And, save for the importance of the action and the size of the targets, this was Marcus Island all over again. Here, as there, you could see what the bombers were doing almost as well as if you had been with them.

You take the one on the right, I’ll take the left one.

The AA battery’s out on the stern of the first carrier. Come in from behind the ship.

Something went through this thing, but she’s holding together. Guess she’ll take the dive.

Briefly and succinctly came the orders to the torpedo planes to slide in. You gathered from repeated directions of squadron commanders that all this becomes as simple and as deliberate as a bit of target practice.

Jap pilot heard

Jap fliers on the same wavelength tried to jam these conversations as the bombing planes hurried home from Midway to learn the bad news at their carriers. One was apparently on the edge of the attack and for some reason was coming our way. He kept mixing his Japanese message with good San Francisco English.

Come in, please.

Acknowledge.

And then, apparently, he came up over the horizon too far away for him to see us. It is said that in excitement, people talk the language to which they are most accustomed. And so did he.

Then, in a very few minutes, the conversations were over and so was the bombing. It was almost frightening to think that this encounter, which had taken on the edges of a decisive battle, had been taken on and finished in a matter of moments.

If we had succeeded in sinking the carriers, we had won; and the Jap planes were now flocking back from what had seemed like a big push and were looking for a landing place they would never find.

One of our aviators mentioned it, a bit awed and as he spoke, you could almost count the unfortunate pilots, the pick of Hirohito’s Navy, dropping into the drink by twos and threes. A ghastly joke indeed to play on a conqueror who was only coming back for a tankful of gas and another load of bombs.

Knew it had happened

At 2 o’clock, we knew that everything has turned out just about that way and, meanwhile, the Army bombers attacking the force of the south had been polishing off some heavy ships – they mentioned battleships. They reported that they had dropped a clunk of a carrier in that vicinity. They said it seemed to be without planes. We did not get the significance of that until later.

There, save for the finishing touches that were to come in two more days of pursuit and slaughter, was virtually the status of the battle as it finished. Whatever else might be done to it, the Jap fleet had been put out of action between dawn and noon.

The smash at Midway and Hawaii was over and the invading force was streaking for Tokyo at its best speed. The big events of the fight were over so far as we were concerned, save one: the carrier load of Jap planes, unable to go home, had wasted the last of its gas in a despairing gesture. They came through our outer patrol in mid-afternoon, spilling a few planes on the way. They met a considerable force of our fighters on the edge of our fleet. That may be what determined them to attack the nearest carrier.

The fight was on and instantly the protecting craft swept into cover. In a few seconds, the sky was black with ack-ack barrage, and threading the smoke balls came the Jap divers performing high-speed hari-kari. The fighters contrived to drive off that attack despite the motivation of despair.

Happened quickly

All this had happened in so few seconds that many of the men in the nearby ships had not even seen it. The fleet went on unperturbed. In the meantime, the Japs, with nowhere to go, flew over the horizon somewhere out of sight, then came back.

The resulting ack-ack was probably the heaviest put over a ship since this war began and we stood open-mouthed as Jap dive bombers came popping out of the black spots trailing peacock tails of flames, then knifed into the sea. Our fighters closed in. The Japs went back over the horizon, some to be shot down by pursuers, some to escape to the dubious alternative of death on the friendless ocean.

But their finish was not entirely useless. They had got a hit on a carrier – a reasonably severe hit. The smash came too late to affect the outcome of the fight. But as a token of what might have happened to us and what actually happened to the Japs all over this area, it was a significantly impressive incident. An escort was left with the ship and we went on, this time suiting our course to the whim of the Japanese.

It was two days before the Japs, running at their best speed, finally got the battered remnants of their fleet over the horizon. Whether some of these, or any of these, were able to get all the way home is something I cannot say.