The Syonan Shimbun (August 6, 1945)

Nippon forces occupy Myitkyi; Pegu in imminent danger, foe admits

Major Nippon successes in Burma fighting

…

Latest U.S. casualties

LISBON (Domei, Aug. 3) – In its weekly war casualty report, the United States War Department yesterday revealed that the American armed forces have now incurred a total of 1,080,727 casualties, according to a Washington dispatch. The latest announcement shows an increase of 18,085 casualties as compared to last week’s figure.

Salzburger Nachrichten (August 6, 1945)

Amerika schreitet voran

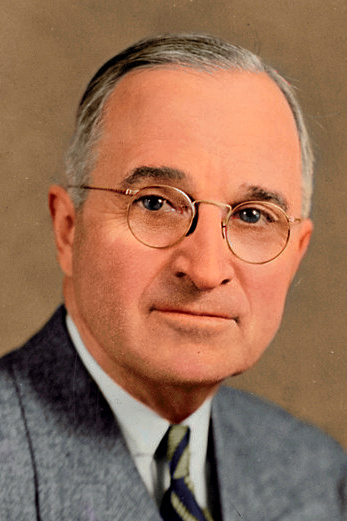

Präsident Truman unterzeichnet drei vom Kongress ratifizierte Gesetze von Weltbedeutung

…

Erklärung Präsident Trumans

KREUZER „AUGUSTA“ (Radio Paris) – Präsident Truman erklärte an Bord des Kreuzers „Augusta“ Zeitungsberichtern, dass auf der Potsdamer Konferenz kein Geheimvertrag irgendwelcher Art abgeschlossen worden sei.

Italien über Potsdam begeistert

ROM (PW) – Italiens Ministerpräsident Parri brachte in einer Erklärung seine Befriedigung über das Potsdamer Kommuniqué, das einen Friedensvertrag mit Italien vorsehe, zum Ausdruck. „Italiens ehrliche Bestrebungen,“ so sagte er, „sich an die Seite der Vereinten Nationen zu stellen und sein Leben auf demokratischer Grundlage zu gestalten, sind anerkannt worden und ich bin glücklich über diese Anerkennung.“

Göring-Prozess im September

LONDON (BBC) – Die Prozesse gegen deutsche Kriegsverbrecher sollen am 1. September in Nürnberg beginnen. Der Hauptanklagevertreter der Vereinigten Staaten, Richter Jackson, wird sein Hauptquartier in etwa zehn Tagen in Nürnberg aufschlagen. Es wurde beschlossen, die Verhandlungen im Justizpalast durchzuführen. Göring, Ribbentrop und andere Nazi werden während der Verhandlungen im städtischen Gefängnis untergebracht. Die Verhandlungen werden einige Wochen dauern.

Falschmünzer verhaftet

BERLIN (OWI) – Korrespondent Raymond Daniell berichtet, dass 45 deutsche Zivilisten wegen Druckens Millionen falscher Markscheine verhaftet worden seien. Die Razzia gegen diese Falschmünzer ist ein schlagender Beweis für die ständigen Maßnahmen, die in dem amerikanisch besetzten Teil Berlins gegen den schwarzen Markt und andere illegale Handlungen ergriffen werden.

Rommel beging Selbstmord

LONDON (BBC) – Generalfeldmarschall Rommel hat, wie von seinem Sohn Manfred Rommel eidesstattlich erklärt wurde, Selbstmord begangen. Rommel wählte diesen Weg, um dem sicheren Todesurteil des Nazigerichtshofes wegen Teilnahme an dem Attentat auf Hitler am 20. Juli 1944 zu entgehen. Die Nazis versuchten lange Zeit, Rommels Tod geheim zu halten. Schließlich setzten sie unter anderem das Gerücht in Umlauf, Rommel sei auf der Fahrt in einem Militärkonvoi während eines britischen Fliegerangriffes verwundet worden.

Statement by President Truman Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima

August 6, 1945, 11:30 a.m. EWT

Sixteen hours ago, an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British “Grand Slam” which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.

The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid manyfold. And the end is not yet. With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development.

It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East.

Before 1939, it was the accepted belief of scientists that it was theoretically possible to release atomic energy. But no one knew any practical method of doing it. By 1942, however, we knew that the Germans were working feverishly to find a way to add atomic energy to the other engines of war with which they hoped to enslave the world. But they failed. We may be grateful to Providence that the Germans got the V-1s and V-2s late and in limited quantities and even more grateful that they did not get the atomic bomb at all.

The battle of the laboratories held fateful risks for us as well as the battles of the air, land and sea, and we have now won the battle of the laboratories as we have won the other battles.

Beginning in 1940, before Pearl Harbor, scientific knowledge useful in war was pooled between the United States and Great Britain, and many priceless helps to our victories have come from that arrangement. Under that general policy the research on the atomic bomb was begun. With American and British scientists working together we entered the race of discovery against the Germans.

The United States had available the large number of scientists of distinction in the many needed areas of knowledge. It had the tremendous industrial and financial resources necessary for the project and they could be devoted to it without undue impairment of other vital war work. In the United States the laboratory work and the production plants, on which a substantial start had already been made, would be out of reach of enemy bombing, while at that time Britain was exposed to constant air attack and was still threatened with the possibility of invasion. For these reasons Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt agreed that it was wise to carry on the project here. We now have two great plants and many lesser works devoted to the production of atomic power. Employment during peak construction numbered 125,000 and over 65,000 individuals are even now engaged in operating the plants. Many have worked there for two and a half years. Few know what they have been producing. They see great quantities of material going in and they see nothing coming out of these plants, for the physical size of the explosive charge is exceedingly small. We have spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history-and won.

But the greatest marvel is not the size of the enterprise, its secrecy, nor its cost, but the achievement of scientific brains in putting together infinitely complex pieces of knowledge held by many men in different fields of science into a workable plan. And hardly less marvelous has been the capacity of industry to design, and of labor to operate, the machines and methods to do things never done before so that the brain child of many minds came forth in physical shape and performed as it was supposed to do. Both science and industry worked under the direction of the United States Army, which achieved a unique success in managing so diverse a problem in the advancement of knowledge in an amazingly short time. It is doubtful if such another combination could be got together in the world. What has been done is the greatest achievement of organized science in history. It was done under high pressure and without failure.

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war.

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

The Secretary of War, who has kept in personal touch with all phases of the project, will immediately make public a statement giving further details.

His statement will give facts concerning the sites at Oak Ridge near Knoxville, Tennessee, and at Richland near Pasco, Washington, and an installation near Santa Fe, New Mexico. Although the workers at the sites have been making materials to be used in producing the greatest destructive force in history, they have not themselves been in danger beyond that of many other occupations, for the utmost care has been taken of their safety.

The fact that we can release atomic energy ushers in a new era in man’s understanding of nature’s forces. Atomic energy may in the future supplement the power that now comes from coal, oil, and falling water, but at present it cannot be produced on a basis to compete with them commercially. Before that comes there must be a long period of intensive research.

It has never been the habit of the scientists of this country or the policy of this Government to withhold from the world scientific knowledge. Normally, therefore, everything about the work with atomic energy would be made public.

But under present circumstances it is not intended to divulge the technical processes of production or all the military applications, pending further examination of possible methods of protecting us and the rest of the world from the danger of sudden destruction.

I shall recommend that the Congress of the United States consider promptly the establishment of an appropriate commission to control the production and use of atomic power within the United States. I shall give further consideration and make further recommendations to the Congress as to how atomic power can become a powerful and forceful influence towards the maintenance of world peace.

Report by Frank Phillips (BBC):

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (August 6, 1945)

Lawrence: Japs also interested in size of our army

By David Lawrence

…

U.S. State Department (August 6, 1945)

740.00119 PW/8-645

Memorandum by the Director of the Office of Far Eastern Affairs to the Under Secretary of State

[Washington,] August 6, 1945

Subject: COMMENTS ON MEMORANDUM FORWARDED BY SECRETARY OF WAR HENRY L. STIMSON ON ‘OBSERVATIONS ON POST-HOSTILITIES POLICY TOWARD JAPAN’

-

The memorandum forwarded by Secretary of War Stimson raises the basic question as to whether the Japanese are to have the major responsibility for running their own country immediately following hostilities with the Allies remaining in the background and exerting a minimum of control, or whether the Allies are to assume supreme authority over Japan in line with a strict interpretation of the term “unconditional surrender” and hence assume the responsibility for all matters in Japan following surrender. The Department of State has in its planning for the post-hostilities treatment of Japan been influenced by the basic fact that until recently this Government has insisted on a rigid interpretation of “unconditional surrender” for Japan and that this policy has been reiterated on several occasions by both President Roosevelt and President Truman. Consequently there was worked out, in conjunction with the War and Navy Departments, basic policy documents and terms of surrender for Japan predicated on the assumption that we would obtain supreme authority over Japan upon its “unconditional surrender” or total defeat.

-

With the issuance at Potsdam on July 26, 1945 of the statement by the Heads of the Governments of the United States, United Kingdom and the Republic of China on terms for Japan which would be acceptable to us at the present time, the possibility of a fundamentally different policy program has been raised and the necessity arises for considering a policy from a different point of view.

-

The Department has been fully aware of the necessity, as clearly set forth in the memorandum forwarded by Secretary Stimson, of advocating policies (a) which would be particularly applicable to Japan as distinct from Germany; (b) which would be politically acceptable to the American people; (c) which would require a minimum period of control over Japan consistent with the fulfillment of our basic objectives; and (d) which would be compatible with our basic war aims. Consequently, it has been recognized in the Department that any policy for Japan to be successful (1) must rely on the Japanese themselves for the development of democratic institutions; (2) must not interfere with the institution of the emperor so long as the Japanese people demand its retention; and (3) must permit the emergence of Japan as a peace-loving nation and its eventual participation in world trade. The Department attempted to reconcile these basic concepts with our declared intention of the unconditional surrender of Japan in document SC-138a entitled “Initial Post-Defeat Policy for Japan,” approved by the Staff Committee on June 26, 1945.

-

In reference to the memorandum forwarded by Secretary Stimson, it should be noted that the views expressed therein are closer to those of the British Foreign Office, as communicated in a memorandum delivered by Mr. Balfour, and are more in line with the Potsdam announcement of July 26, 1945 than are the policies advocated in “Initial Post-Defeat Policy for Japan.” There are obvious disadvantages to both a plan which envisages complete control over Japan by the Allies and to one in which the role of the Allies is largely supervisory. The memorandum forwarded by Secretary Stimson points out many of the weaknesses in the former plan. On the other hand, it must be realized that if a United States policy program is based entirely on the assumption that the Japanese will develop, largely on their own initiative, “a genuine democratic movement” and such a movement does not develop, the Allies will be faced with the choice of either stepping in and taking over more control or leaving the Japanese to develop internally as they see fit. It is doubted, moreover, if the philosophy of militarism can be completely and permanently discredited in the minds of the Japanese people unless the extent of their defeat is brought home to them by the occupation, even if only for a brief period, of a substantial part of their territory. Furthermore, recent public opinion surveys in this country show that a third of those questioned advocate the execution of the Emperor after the war, a fifth voted for his imprisonment or exile, a sixth wanted a court to decide his fate, while only three percent supported his use by the Allies. It is questionable, therefore, whether or not it would be politically practicable for the Allies to use the Emperor to the extent suggested in the memorandum. However, if Japan accepts in the near future the terms as defined at Potsdam on July 29 [26?] 1945, many of the suggestions made in the memorandum forwarded by Secretary Stimson would be more appropriate.

-

On the other hand, if Japan does not accept the Potsdam terms and the Allies are forced to fight their way into the main Japanese islands and to defeat the Japanese Army in the homeland, it may be that no central Japanese authority will be in existence and that the Allies may be forced to assume the supreme authority of Japan and to exercise that authority for a limited period.

-

If Japan capitulates before an invasion of the homeland or the defeat of her armed forces in the field, however, a compromise plan might be preferable which contained parts of the old concepts of supreme authority and the new concept of a surrender based on specific terms and with the Allies exercising only partial control.

-

Such a partial compromise is in fact under consideration by the State, War, Navy Coordinating Sub-Committee for the Par East. Tentative plans for the control of Japan envisage three main periods. The first of these, which would probably not exceed 18 months, would be one in which the Supreme Allied Commander for Japan would assume authority over Japan and would enforce disarmament and demobilization. These military aspects of Japanese surrender might be carried out either through partial or complete occupation of the home islands. The Japanese administrative structure would be used to the fullest possible extent but all policies would be decided by the supreme commander. The Emperor and his immediate family would be placed in protective custody so that the Institution of the Emperor would, in reality, be continued. The second period, as at present envisaged, would be characterized by the transfer of authority in Japan from the supreme commander to an Allied Supervisory Commission, composed of civilian representatives from the major Allies at war with Japan. The policies of the Commission would be implemented by the Japanese themselves. The Commission would support such measures as would facilitate development by the Japanese of democratic institutions. Limited Allied military, naval and air forces would be stationed at points from which the policies of the Supervisory Commission could be enforced when necessary. As the Japanese developed a willingness to follow the suggestions of the Supervisory Commission and increasingly cooperated with the Allies, authority would be turned over to the Japanese. This second period should likewise be limited in duration and such controls as were necessary for a more extended period could be exerted through the control of exports and imports. It is envisaged further that basic differences in policies between ourselves and our Allies could be settled in the proposed Far East Advisory Commission.

-

If circumstances warranted it, a more complete compromise might be preferable under which the Allies would exercise supreme authority over Japan during a short initial period with only partial occupation. At the beginning of the second period of control, however, authority in Japan might be transferred from the supreme commander to Japanese governmental authorities and any Allied Supervisory Commission which might be formed to continue control over Japan would have only limited authority. It is believed that such a compromise plan would meet many of the points raised in the above-mentioned memorandum, would be closer to the ideas expressed by the British Foreign Office, would be workable from a practical point of view and would, at the same time, give us reasonable assurance that our basic objectives towards Japan could be achieved.

In summary:

-

The United States early announced that it would demand the unconditional surrender of Japan;

-

The Potsdam Proclamation, July 26, 1945, announced terms of surrender, which might bring about an early capitulation of Japan;

-

The memorandum presented by Secretary Stimson presents a plan which is along the line and in amplification of the Potsdam Proclamation and in harmony with the present views of the British Foreign Office.

-

If the Japanese Government should in the near future offer to surrender, the terms of the Potsdam Proclamation, possibly amplified along the lines of the submitted memorandum, would be applicable;

-

If, however, it is necessary to invade and conquer Japan, it is possible that, as in the case of Germany, no Japanese Government will be in existence. In such a case the early plans of the Department would naturally come into operation;

-

If Japan should surrender at some time before the complete conquest of the main islands, the terms of surrender to be enforced on Japan would depend upon the conditions, political, military and economic, existing at the time.

J[OSEPH] W. B[ALLANTINE]