In part 4 we return to the continuing development of RAF Coastal Command and its attempts to combat the growing U-boat menace as the Battle of the Atlantic continues through 1941 and into 1942.

Sources:

“The Far Distant Ships” by Joseph Schull, ISBN-10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

“North Atlantic Run” by Marc Milner, ISBN-10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Joseph Schull’s work, published 1985)

“Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War: Volumes 1 & 2” ISBN-10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

“The Corvette Navy” by James B. Lamb, ISBN 0-7737-3225-X, (A shorter book that contains personal anecdotes of Mr Lamb’s service aboard corvettes during the Battle of the Atlantic, and later his involvement in the D-day landings)

“The Essential Aircraft Identification Guide: Allied Bombers 1939-1945” by Chris Chant, ISBN 978-1-905704-70-5

“The World Encyclopedia of Bombers” by Francis Crosby of the Imperial War Museum, Duxford. ISBN 10 1780192053

“The Essential Aircraft Identification Guide: Luftwaffe Squadrons 1939-45” by Chris Bishop, ISBN 1-904687-62-8

“Military Aircraft Visual Encyclopedia” published by Amber Books, ISBN 978-1-906626-71-6

“The Crucible of War: 1939-1945, The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force Volume III” Written by Brereton Greenhous, Stephen J. Harris, William C. Johnston, and William G.P. Rawling. ISBN 0-8020-0574-8

Pictures are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Library and Archives Canada, Uboat.net, The Rooms Provincial Photo Archive, and other sources. I only use photos that exist in the Public Domain unless otherwise stated.

Coastal Command, 1941-42

The end of 1940 saw a number of changes come to Coastal Command. Most of the Avro Ansons in service to CC were replaced with newer Bristol Beauforts. It should be noted that the Beaufort was primarily used on anti-shipping missions as a torpedo bomber. It excelled in this role and would become the de facto anti-shipping strike craft for the remainder of the war. I make note of this here because I feel that British anti merchant shipping operations against German vessels is a little known contribution to the war, and as a reminder that Coastal Command had other priorities besides ASW and convoy coverage. Coastal Command was preparing to acquire their first Consolidated Catalinas/Cansos, as well as more Bomber Command hand-me-downs in the form of Armstrong Whitworth Whitleys (two squadrons) and Vickers Wellingtons (one squadron). The Hudson had also continued to trek its way from the US to Canada to Newfoundland to Britain, and there were more arriving every month. There was also a single squadron of the much anticipated B-24 Liberator in the process of forming.

Sidenote: Coastal Command also changed up their aircraft camouflage scheme to the white and gray scheme that would define them for the rest of the war.

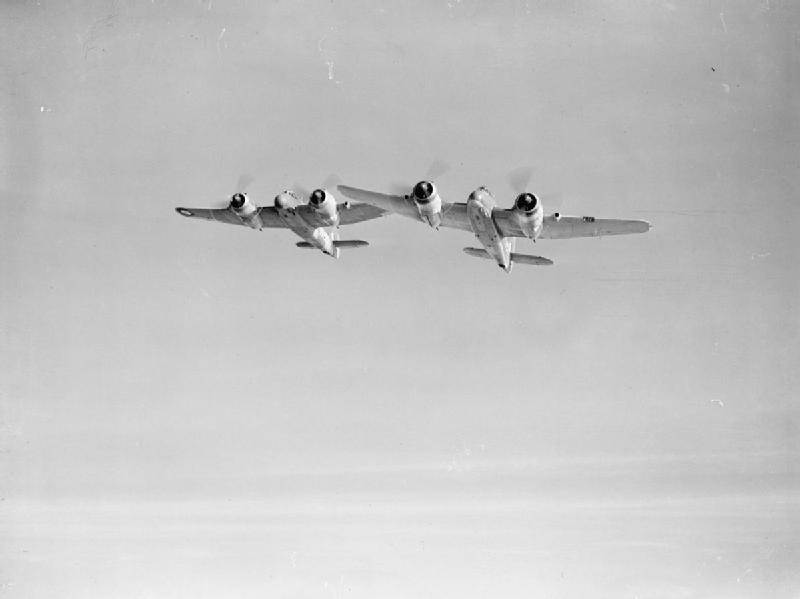

(Coastal Command Vickers Wellingtons in Gibraltar. Date unknown)

1941 would be a year of crisis for Coastal Command, without much visible hope for improvement in sight. There were, however, a few notable successes, the beginnings of greater capability, and a more effective concentration of effort. Coastal Command wanted a number of things to improve their ability to hunt and kill U-boats. They wanted a depth charge more suited to aerial attack, more radios to facilitate better ship/aircraft communication, more reliable/longer ranged radar, and the means to illuminate U-boats at night (slow-dropping flares or searchlights). A tall order to fill to be sure, but all of it was deemed essential in order for CC aircraft to be effective in their work. The start of 1941 was marked by dreadful weather, which was as much a hindrance to U-boats and the Luftwaffe as it was to Coastal Command. Convoy losses declined from Happy Time highs, and the British were afforded a little more breathing space.

The breathing space evaporated as the weather improved and by mid-February losses increased as Germany devoted more U-boats and aircraft, not to mention a few more surface raiders, to the task of destroying Allied merchant shipping. That Spring saw the introduction of the aforementioned 250-lb Mark VII depth charge. Although this weapon would ultimately be declared the CC charge of choice, this early version was not yet that weapon. Its charge was Amatol, and had only 30-50% the explosive power of a Torpex weapon. The pressure-sensitive detonators were also still set to a minimum of only 50 feet, much too deep to destroy submarines that were only just below the surface. They had also not yet caught on to the effectiveness of the “Total Release” tactic.

Losses continued to rise. In April 1941, losses amounted to 654,304 tonnes, many to Coastal Command’s new FliegerKorps Atlantik counterpart in France. Germany’s U-boat fleet was around thirty boats, with around twelve of them on patrol (in the Atlantic) at any one time. Plans were in the works for expansion and higher operational tempo, however, and that number would be sixty boats by the end of the Summer, with thirty-nine deployed in the Atlantic.

By June 1941, Coastal Command had (after losses, replacements, and reshufflings) around 340 aircraft all told. Although this was not a great increase in raw numbers, they had many more “capable” aircraft at their disposal. The medium bombers they received from Bomber Command all had decent range and the payload capacity for depth charges, but there were other issues present. They had, after all, been deemed lesser aircraft by Bomber Command and were beginning to be superseded by superior ones. The greatest improvement came in the form of long-range General Reconnaissance squadrons who could directly cover the convoys. The B-24s in the works for Coastal Command were modified for precisely this purpose. Equipment not strictly needed for ASW was removed, and additional fuel tanks were added in its stead. These were the first VLR (Very-Long-Range) Liberators, armed with eight depth charges, they could range anywhere from 800-1000 miles out from base and still spend at least one third of their flying time over the convoy, on a sortie lasting up to 14 hours long.

(This picture, taken October 8th 1943, depicts U-643 down by the bow after being depth charged by Liberators of Coastal Commands No. 86 Squadron. This submarine was part of a pack attack on SC-143, but the timely arrival of the Liberators saw three of the attacking U-boats destroyed on the same day. This picture was taken from a Liberator that arrived on the scene after the battle was over.)

The Catalina flying boat was also much anticipated, as they would finally allow the retirement of the Stranraers and Lerwicks. The Catilina’s 25 hour endurance allowed it to provide convoy escort up to six hundred miles from base, although it’s rather slow cruising speed of only 115 miles per hour was a disadvantage. The first Catalinas arrived at the end of April 1941.

German tactics at this point in the battle revolved around lone subs locating a convoy and shadowing it whilst other boats were vectored in for a group attack. The initial contact submarine had to maintain an effective shadow of the convoy during the daytime, constantly noting changes in the course and speed of the convoy in order to ensure that the highest number of U-boats could participate. This crucial aspect could only be attained by U-boats on the surface. Modern submarines can give people the wrong ideas, but World War II era U-boats were very slow when submerged, usually slower than the convoy, and even if they were not, it was extremely difficult to keep track of the convoy from beneath the waves. Thus, the objective of Coastal Command convoy escort planes was mostly suppression of the shadowing boat. If the submarine could be driven back again and again, he could lose the convoy, and the entire pack would be thrown off the scent. It was a hard thing to get down on paper for posterity’s sake. Coastal Command could never keep track of how many convoys were not attacked because of their actions, only the ships that were sunk when they failed. I will not go into full details here, as that information is available if you go looking for it. Suffice to say that even during the climax of the Atlantic Battle, Coastal Command was still seen as a lesser service by some in RAF command.

In the Fall of 1941, things changed again. The U-boats began pushing further out into the Atlantic, further and further beyond the range of Allied aircraft. By this point, the area known as the mid-atlantic air gap was starting to take shape. The establishment of squadrons at RCAF Stations Torbay and Gander, Squadrons in Iceland, and longer ranged aircraft at home in Britain had carved out great swathes of the ocean that could now be considered “safer” than they had been earlier in the war. The convoy routes were also, at this time, still cutting far to the north near Greenland in their attempts to route around U-boat packs. This had the secondary effect of keeping them within range of land-based aircraft for longer periods of time. Coastal Command also now had an updated ASV (air to surface vessel) Radar ready for issuing to squadrons for the purpose of detecting submarines on the surface, and they also began instruction in the “Total Release” tactic. Both were met with considerable doubts. Air crews were aware of the fickle nature of radar, and the Total release tactic dedicated all the ordnance onboard into a single attack on a single U-boat, expending everything they had with one shot and removing the ability to attack further contacts that may threaten a convoy. ASV Mark I had been in service before the war, but was unsuitable for U-boat detection and convoy escort crews put little faith in it. ASV Mk. II was greatly improved in terms of reliability, but not capability. It still had serious difficulty detecting U-boats even when they were fully surfaced. With decks awash, it was hopeless. In fairness, there were a few attacks conducted at night thanks to the new system, which no doubt unnerved U-boat commanders who assumed they were at their safest when night fell. Development of better systems was constantly ongoing behind-the-scenes, and I will cover the development of better systems in a later part.

Autumn of 1941 also saw Coastal Command finally lay out exactly what they wanted in terms of aircraft numbers and types. They were finished with poorly timed hand me downs and half measures, and wanted 150 Catalinas and 76 Sunderlands to equip 26 Flying-Boat squadrons, 32 Liberators and 32 Whitleys or Wellingtons to equip four long-range General Reconnaissance squadrons, 64 Mosquitoes and 150 GR Hudsons to equip 15 medium to long range units, 128 Beauforts to equip 8 torpedo bomber squadrons, and 160 Beaufighters to equip 10 long range fighter-squadrons. They had already hit some of these markers. The Ansons were gone, all replaced by Beauforts. Catalinas and more Sunderlands were in the works.The Liberators and Whitley/Wellingtons were coming up to full strength, and they now had more than enough Hudsons to fulfill the 150 that were deemed necessary. The Beaufighters also finally gave Coastal Command a weapon capable of engaging the Condors.

(A pair of Coastal Command Beaufighters of No. 252 Squadron in flight. Picture taken January 1941)

Up until this point, Coastal Command did not really have an aircraft capable of directly engaging them. The Sunderlands were the only aircraft that had the firepower but could not catch up with the far speedier Luftwaffe craft. By late 1941 there had only been five recorded actions between Coastal Command Aircraft and the Condors. The results were two RAF aircraft lost for two condors destroyed and one damaged. The Beaufighter came with four 20-mm cannons and a top speed 160 km/h faster than the Condors’ top speed. With a suitable long range heavy-fighter in place, it quickly changed the situation in the RAFs favor. Condor operations became more and more dangerous as 1941 moved into 1942 and then forward into 1943. A Condor alone was no match for a group of the new aircraft, and the Luftwaffe began losing aircraft much more frequently. The introduction of the famed Mosquito into Coastal Command service, and their en masse use over the Bay of Biscay signalled the death of the Condor menace, with further operations deemed ‘suicidal’.

(A Condor of KG. 40 sinking in the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland. This aircraft was shot down by a Lockheed Hudson Mk. V of No. 233 Squadron. Picture taken July 23rd, 1941.)