In Part 3 I will be discussing the rugged beginnings of Allied air strength on the other side of the Atlantic. This part will mostly be early war, and will contain a lot of general information on the formation and growth of the RCAF. The US air contribution will be discussed somewhat here, as it relates to RCAF development, but they will primarily be discussed in a later part, once I have passed the point of their entry into the war.

EDIT: My new book arrived, and has mountains of information for me to go over, I will update this page accordingly.

Sources:

“The Far Distant Ships” by Joseph Schull, ISBN-10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

“North Atlantic Run” by Marc Milner, ISBN-10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Joseph Schull’s work, published 1985)

“Reader’s Digest: The Canadians at War: Volumes 1 & 2” ISBN-10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

“The Corvette Navy” by James B. Lamb, ISBN 0-7737-3225-X, (A shorter book that contains personal anecdotes of Mr Lamb’s service aboard corvettes during the Battle of the Atlantic, and later his involvement in the D-day landings)

“The Essential Aircraft Identification Guide: Allied Bombers 1939-1945” by Chris Chant, ISBN 978-1-905704-70-5

“The World Encyclopedia of Bombers” by Francis Crosby of the Imperial War Museum, Duxford. ISBN 10 1780192053

“The Essential Aircraft Identification Guide: Luftwaffe Squadrons 1939-45” by Chris Bishop, ISBN 1-904687-62-8

“Military Aircraft Visual Encyclopedia” published by Amber Books, ISBN 978-1-906626-71-6

“The Crucible of War: 1939-1945, The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force Volume III” Written by Brereton Greenhous, Stephen J. Harris, William C. Johnston, and William G.P. Rawling. ISBN 0-8020-0574-8

Pictures are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Library and Archives Canada, Uboat.net, The Rooms Provincial Photo Archive, and other sources. I only use photos that exist in the Public Domain unless otherwise stated.

The RCAF, 1939-1941

It will probably surprise none of you to hear that the RCAF was underfunded and undermanned at the start of the war, possessed too few aircraft, and most of what it had was outdated. Most of what it had was also not really intended for actual military use, as the RCAF spent the inter-war years mostly performing missions for other government services, such as forest patrolling, aerial photography, and police liaison. There were attempts to remedy this in the late 1930s, with 1938 seeing the RCAF begin the transition to actual military work. Like the government’s pre-war efforts to increase naval strength, this was too little too late. Fortunately, and also like the navy, it was in line with the governments political aims to promote the air force as a primary contribution to the allied war effort, and men and money flooded into an organisation that was willing to welcome it, but lacked the facilities necessary to house and train them all, nor a real plan to spend this cash.

The RCAF command actually had done some work on a planned, measured increase in size and capability over the first two years of the war. Events soon overtook that and, like the navy, this pre-war planning went right out the window. Suddenly blooming budgets brought a rather haphazard rush to replace outdated airframes, sometimes with aircraft that, while technically more up to date, were just as obsolete as their predecessors.

Discussing strength and disposition of forces, my sources state that on August 31st 1939, the RCAF possessed 4061 personnel, all ranks, of whom only 3048 were regulars. Of this number only 298 were Permanent Force Officers, and of these only 235 were pilots. One fifth of that number had only completed training in the last months of 1938. So slow was promotion and so small was the officer corps that in 1939, the highest ranking officer who was not a World War 1 veteran was C.R. Slemon, who had joined in 1924, and was only a squadron leader serving as a staff officer at Western Air Command HQ. This left policy and direction to the Great War flyers who had joined the fledgeling RCAF between 1919 and 1923, when the only requirement was a good flying record under the RAF during the previous conflict. While most of them had finished high school, only four of them had university degrees (all from the Imperial Defence College in London) and they all filled technical positions. Around twenty or so had been to the RAF Staff College at Andover. While this education was surely a benefit to them, the IDC taught geopolitics and the principles of imperial defence, and Andover taught the theory of air power with a heavy emphasis on strategic bombing. None of that was very helpful when it came to dealing with the problems they were faced with in 1939. They needed to know how to mobilize, organize, train, and equip not only what they already had at their disposal, but the massive influx of new recruits.

(The men of No.3 Squadron RCAF, posing for a picture in front of their Westland Wapiti aircraft, circa 1938)

270 aircraft were organized into twenty full-time operational squadrons, though many of these squadrons were undermanned, and in reality they only had about eleven full squadrons worth of aircraft and men. That number grew to twenty three by October of 1939, but given the undermanning of many of them, it is more accurate to think of fifteen as a real marker of operational strength. Nevertheless, of the twenty squadrons available in August 1939, twelve were dedicated to homeland defense (auxiliary/reserve), and eight were for overseas service (active). RCAF Command presented Cabinet with a new expansion plan on September 5th, outlining how many squadrons they planned to add in the future, how current units would be consolidated, and how new forces would be divided between home defence and expeditionary service. These plans made no mention of what aircraft these new squadrons were to be equipped with. Concerning indeed, considering the fact that the RCAF was hamstrung by the most mish-mash combination of aircraft of all forces discussed so far, outstripping both Coastal Command and the Luftwaffe at twenty different aircraft types, all obsolete save a few modern bombers and fighters.

Moving directly to information relevant to the Battle of the Atlantic from here onward.

For my purposes, the RCAF also possessed relatively few military facilities from which to range out over the Atlantic for maritime patrols. There was an RCAF Station at St. Hubert, Quebec, an RCAF Station at Saint John, New Brunswick, and RCAF Stations at Sydney, Halifax, and Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. St. Hubert was too far inland (although in a good position to patrol the St. Lawrence River), Saint John was not a terrible location but was extraneous in light of the better options in Halifax. For those of you who are not aware, Dartmouth is only just across the water from Halifax, so the two bases were essentially the same area, well placed for patrolling the Gulf of St Lawrence and the Cabot Strait but not for ranging far out to sea. Sydney was much in the same boat, but aircraft based from there could theoretically patrol the Strait of Belle Isle.

(RCAF Station Gander in 1944.)

The Island of Newfoundland once again appears as an essential base for Atlantic operations. The Newfoundland Airport (now Gander International) was one of the few “proper” civil airports in the maritimes and was singled out as a possible location from which to base aircraft. While the airport was not “officially” placed under Canadian military control until 1941, practically speaking it was an RCAF facility in all but name from 1940 onwards, and military aircraft were a common sight. Indeed, Gander Airport would go on to serve as a base for both RAF Ferry Command and the US Air Transport Command, and around 20,000 Allied bomber and fighter aircraft passed through on their way to Europe, mostly for maintenance and refueling. In November 1940, Captain D.C.T Bennett left Gander for Europe, leading the first flight of seven Lockheed Hudson’s across the Atlantic. The first flight of Ferry Command. A strong Canadian Army presence was also established.

There were a few other promising options. While not a proper airport facility, Botwood, Newfoundland was already a developing base for seaplane flights, with both PanAm and BOAC using Botwood as a terminal for their Atlantic crossings. The first Trans-Atlantic passenger flight left Botwood on June 27th, 1939, with Yankee Clipper flying to Foynes, Ireland. The RCAF saw the potential and quickly made plans to begin construction of a military installation. Canadian Army troops garrisoned the town and constructed facilities of their own. Additions included:

- A concrete slipway

- A tarmac

- Four bunkers

- Two hangars

- Full size barracks

- A water system

- Full scale military hospital

As at Gander, the Army was also responsible for protection, and gun installations were built on Phillip’s Head and Wiseman’s Cove. 10-inch gun emplacements to protect the entrance to the harbour. The Army also built a number of anti-aircraft gun batteries throughout the community. At its peak the base was home to 10,000 RCAF and RAF personnel. Celebrity visitors who overnighted included Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Bob Hope (who performed for RCAF Coastal Command).

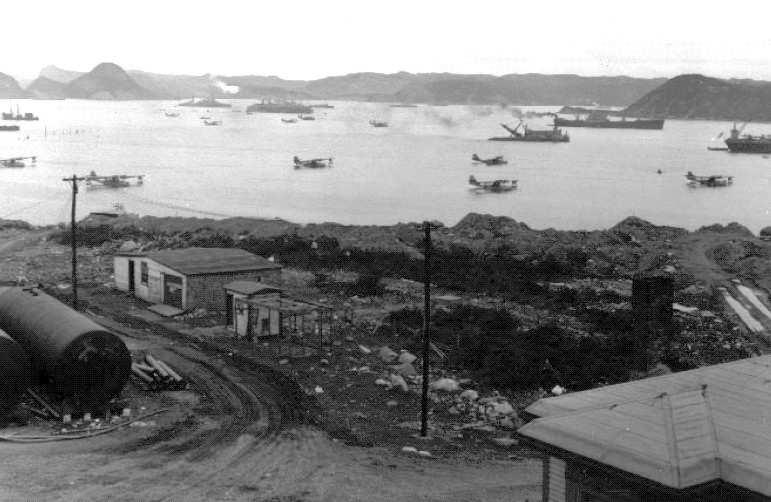

Botwood and Gander were important installations, and more would be forthcoming as the war progressed. As part of the Destroyers-for-Bases deal, the US constructed a number of military facilities of its own which would increase capabilities. Naval Station Argentia hosted naval flying boats, and the Army Air Forces built four bases of their own including Pepperell Air Field (north of St. John’s), Army Air Field Stephenville (West Coast of Newfoundland) , Army Airfield Goose Bay (in Labrador, still exists as an RCAF base for SAR), and Army Air Field McAndrew (which was the USAAF component of Argentia).

Canada itself would add further strength, with the construction of RCAF Station Torbay (present-day St John’s International Airport) beginning in April 1941 after agreements were made with the Newfoundland Government. The first aircraft would not begin using Station Torbay until October 18th, 1941 (it was an emergency landing, the base was not yet officially open).

(US Navy ships and flying boats in Placentia Sound off Argentia, Newfoundland, circa 1942.)

The RCAF Home Defence was divided in two different areas of operation. RCAF Eastern Air Command (EAC) and RCAF Western Air Command (WAC). Eastern Air Command was responsible for Atlantic/European operations and was HQed at Halifax, Nova Scotia. A number of squadrons were disbanded just before the war, and aircraft and personnel transferred to “buff up” other squadrons. No.3 Squadron for example, was merged with No.10 Squadron on September 5th, 1939.

It’s order of battle on September 10th, 1939 was as follows:

- No. 1 Squadron (flying Hurricane fighters)

- No. 2 Squadron (flying the Armstrong Whitworth Atlas biplanes. Army Cooperation was apparently their function)

- No. 5 Squadron (flying our old friend the Supermarine Stranraer flying boat)

- No. 8 Squadron (flying Northrop Delta transport aircraft)

- No. 10 Squadron (flying Westland Wapiti general-purpose biplanes)

- No. 116 and No. 117 Squadrons had no aircraft, and were both disbanded before the end of 1939)

Of these squadrons, only No. 5 and No. 10 were coastal patrol squadrons at the start of the war, designated Bomber Reconnaissance under RCAF organizational structure. No.8 Squadron was strictly a Bomber squadron when the war broke out, but practically speaking its aircraft (the Northrop Delta) was just as capable of reconnaissance.

It had been brought into RCAF service for the purpose of long range survey missions over the vast Canadian wilderness, something it proved extremely good at, and most of them had been built in Canada under license by Canadian Vickers Limited. It had a range of 2655 Km and could be fitted for wheeled, ski, or float undercarriages, making it one of the more useful aircraft in Canada’s inventory. It carried no armament however, and the rough ocean swells and saltwater corrosion quickly revealed the aircraft’s unsuitability for seawater landings. It was reverted to wheeled undercarriage within two months of the outbreak of war. They were all removed from active service by 1941, but saw new life as instructional airframes at training schools.

The Supermarine Stranraer has already been discussed in my Coastal Command post. Suffice to say, it was outdated, but Canada could not replace it as quickly as Britain could, and they remained in service far longer.

The Westland Wapiti was not a dedicated coastal patrol aircraft, but in fact a general military biplane that could be used on floats for water takeoff and landing. It had a pitiful range of only 580 Km, and an equally useless armament of one forward firing Vickers machine gun, one rear firing Lewis gun mounted on a Scarff Ring, and up to 580 lbs of ordnance. The RCAF quickly purchased 20 Douglas B-18 ‘Bolo’ aircraft from the US to replace them, and by mid-1940 the Wapitis were gone. The Canadian Bolos were renamed Digby Mk.1s and served in the anti-submarine role until 1943.

The Digby was a step up from the Wapiti, with a range of 1450 Km and an ordnance capacity of 4400 lbs. They have one U-boat kill to their credit in service with No.10 Squadron. On October 30th, 1942, a Digby flown by Flying Officer F. Raymes attacked and sank U-520 with depth charges off the east cast of Newfoundland.

(A Douglas Digby in RCAF service. Picture taken April 6th, 1941.)

To summarize, by the Fall of France, No.5 Squadron was flying Stranraers from Dartmouth, No.8 Squadron was flying Deltas from Sydney, and No.10 Squadron was flying Digby’s from Halifax. None of the aforementioned bases built in Newfoundland were yet available for use except Gander Airport. By late 1940 No. 10 Squadron had moved to Gander to begin operations over the Atlantic, and remained there until 1945. No. 5 Squadron and No.116 Squadron (reformed in 1941) would occasionally reinforce them from time to time, but it was never on a permanent basis. RAF, USAAF, and USN anti-submarine patrol squadrons would all call Gander home over the course of the war.

Sorry for the lack of information on this particular area. There is very little information regarding the history of the RCAF (in the ASW role) in the early war, as most of my sources focus very much on its overseas service during the Battle of Britain and beyond, or on the BCATP (British Commonwealth Air Training Plan).

I am expecting a new book in the mail which will hopefully give me more information on this subject.