Thread to analyze one of the most controversial battle in the Korean war. A myth created by the Chinese state media.

Forgotten by the Americans, and the Chinese just made a film about it.

Thread to analyze one of the most controversial battle in the Korean war. A myth created by the Chinese state media.

Forgotten by the Americans, and the Chinese just made a film about it.

Unlike in the West, where the Korean War is often called the “forgotten war,” in China, the conflict has been actively promoted for decades. If you ask a Chinese person, they’ll probably say the Korean War was fought to stop American imperialist expansion. Some might even argue that the sacrifices of the brave People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) troops in Korea helped China secure its seat on the UN Security Council. Recently, Chinese state media released several major films depicting their “great victories” in Korea:

And finally, - The Volunteers: The Battle of Life and Death, released just a month ago, centred on the Battle of Cheorwon.

But where even is Cheorwon? For Western historians, the “Battle of Cheorwon” (铁原保卫战) might be an unexpected reference. Could it be a translation error? No way this was never heard of.

Ask any Chinese person, and they will likely tell you that the Battle of Cheorwon is regarded as the most heroic engagement of the Chinese army, with the last stand of the People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) 63rd Corps forever changing the course of the war. According to the narrative put forth by the Chinese Communist Party, this battle inflicted 15,000 casualties on U.S. forces and marked the point at which further UN advances north were effectively stopped for the remainder of the conflict.

Origin:

In the 2000s, a patriotic Chinese blogger named Sa Su shared a story about a battle between the U.S. military and the Chinese 63rd Corps before the occupation of Cheorwon. He wrote an article titled Burning Iron (铁在烧), which highlighted the bravery of Chinese Volunteer Army in Cheorwon, and brought the “forgotten battle” into the public eyes. Sa Su’s work resonated with many readers. To emphasize the importance of this battle, some even shared a story suggesting that “U.S. Far East Commander General Matthew Ridgway faced criticism from the American public due to his challenges at Cheorwon.”

This story soon gained traction, and many people, including some official media commentators, began to mention the 63rd Corps and the “Cheorwon Blocking Battle” as if it played a key role in holding back American advances. Sa Su’s work even inspired the PLA TV Propaganda Center to produce a five-part documentary titled Burning Iron: The Cheorwon Battle Records of the 63rd Corps.

For a time, articles and discussions about the “Battle of Cheorwon” became widely popular online, focusing on the courage of Chinese Volunteers and the challenges faced by American forces. However, historically, this battle was part of the failed PVA Spring Offensive (fifth phase offensive), which was ultimately a strategic defeat and withdrawal for the Chinese forces. During the ceasefire negotiations, the Chinese and North Korean sides requested the return of Cheorwon—a goal that was difficult to achieve through diplomacy alone, given the battle’s outcomes. After the war, North Korea lost approximately 4,000 square kilometres of territory, including Cheorwon.

Why is Cheorwon Important?

Cheorwon is located in central Korea, approximately 40 kilometres north of the 38th parallel and was part of North Korea before the war. The Kwartal Labor Party Office, situated in the area, served as the headquarters for the Workers’ Party of Korea and is regarded as a revolutionary “holy site” similar to Yan’an in China. Due to its relatively flat terrain, Cheorwon is a crucial junction for the Gyeongwon Railway Line, which connects Seoul and Wonsan, making it the most significant transportation and communication hub in central Korea. Furthermore, Cheorwon has historically served as a gathering point for Chinese and North Korean forces launching offensives south of the 38th parallel and as a rear supply base.

What is the Background of the Battle of Cheorwon?

In the wake of the catastrophic defeat suffered by the Chinese Volunteers Army during the Fifth Phase Offensive, the entire PLA army retreated in disarray, prompting the UN forces to execute their planned push to the “Kansas Line.” General Matthew Ridgway, commander of the Eighth Army, recognized Cheorwon as a vital logistical base and strategic transportation hub from which Chinese and North Korean forces had repeatedly launched their attacks. He believed that capturing Cheorwon was essential to prevent the Chinese and North Koreans from regrouping and launching further offensives.

To achieve this objective, General Ridgway ordered the allied forces on the central front to launch an offensive northward, advancing 25 to 30 kilometres from the Kansas Line to seize two crucial positions at the southern edge of the “Iron Triangle”—Cheorwon and Kimhwa. This would enable the Allies to control the central nerve center of Chinese and North Korean strategic operations. The operation was codenamed “Operation Piledriver,” initially scheduled to commence on June 1, 1951, but was later postponed to June 3 due to heavy rain.

The U.S. 3rd Infantry Division was tasked with the main assault on Cheorwon, advancing through the Han Tan River Valley towards their target. Simultaneously, two regiments from the 1st Cavalry Division (the 5th and 7th Cavalry) were to clear the area southwest of Cheorwon and encircle it along Highway 33, with the operation expected to be completed within two weeks.

Had General James Alward Van Fleet adhered to strict orders and halted the advance at the outskirts of Cheorwon (the Kansas Line), this battle might have been celebrated by the Chinese media as another tremendous propaganda victory just like the Battle of the Triangle Hill.

After capturing Cheorwon, the UN forces briefly occupied Pyonggang to the north before General Ridgway ordered a withdrawal, allowing the Chinese Volunteer Army to retake Pyonggang. This turn of events has been portrayed in the Chinese narrative as a monumental victory in a life-and-death struggle, despite the fact that it was the UN’s decision to pull back that facilitated the Chinese reclaiming of territory. This irony highlights the way the conflict has been framed in terms of heroism and triumph.

Why Was the 63rd Corp Forced to Engage?

The 63rd corps, part of the 19th Army, originally hailed from the 3rd Corps of the North China Field Army (华北野战军的3纵 ). Following the Xinfeng Campaign, it was bolstered by a substantial influx of veterans from the former 35th Corp of the National Revolutionary Army, resulting in a combat unit known for its exceptional prowess—one of the finest in North China.

By early 1951, the 63rd Corps had fully modernized its arsenal with Soviet-style equipment and heavy weaponry, deploying over 50,000 troops to Korea to take part in the Fifth phase offensive. Yet, right from the outset, the 63rd Corps encountered formidable resistance; upon crossing the Imjin River, it faced fierce opposition from British forces. Three divisions found themselves locked in a grueling 50-hour standoff against a single British battalion of around 700 men at Snowy Horse Ridge, demonstrating both the tenacity of the enemy and the challenges ahead.

When Peng Dehuai ordered a withdrawal on May 23, the 63rd Army, acting on its own initiative, retreated a day early, preserving its strength and successfully returning to its starting point north of Cheorwon. However, this decision proved to be a fatal blow to the nearby 60th Corps and resulted in the total annihilation of the PVA 180th division.

Enraged by this insubordination, Peng Dehuai commanded the 63rd Corps along with the 65th Corps’ 194th Division, to turn back immediately and defend Cheorwon. He insisted that they hold their ground at all costs, even if it meant sacrificing everything, and forbade any further retreat. This unwavering order set the stage for a fierce and desperate fight, underscoring the gravity of their situation and the relentless spirit that would define their engagement in this pivotal conflict.

The Battle of Cheorwon

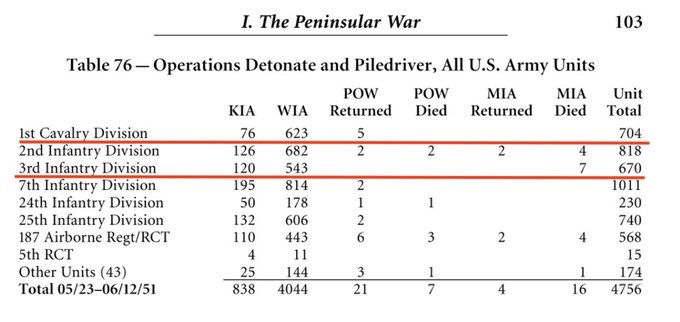

According to Chinese military history, the 63rd Corps, along with the attached 194th Division of the 65th Corps, engaged in a 13-day defensive battle at Cheorwon against 50,000 U.S. troops, reportedly inflicting 20,000 casualties on the enemy. However, U.S. military records present a different picture. In reality, only five U.S. regiments (the 5th and 7th Cavalry, the 7th, 15th, and 65th Infantry) participated in this engagement over those 13 days, with total U.S. casualties amounting to just 165, including the loss of Puerto Rican soldiers from the 65th Infantry.

Notably, the attack on Cheorwon occurred without the participation of South Korean forces, meaning there were no South Korean casualties during this battle. If we consider the KATUSA (Korean Augmentation to the United States Army) personnel within the U.S. forces and apply a 20% casualty estimate, the KATUSA losses would be approximately 32 soldiers. When factoring in the Philippine battalion and other attached units, including four artillery battalions, the total fatalities for the coalition forces would not exceed 250.

According to the international norm of a 3:1 casualty ratio, if we extrapolate the wounded based on the reported deaths, the total number of casualties for the UN forces during the 13 days of the Cheorwon offensive would not surpass 1,000. This disparity in reported casualties explains why historians of the U.S. military rarely mention this battle when recounting the bloodshed of the Korean War.

(It’s not worth it to be considered as a separate battle, the US just sees it as a segment of operation piledriver”).

U.S. Casualty from Operation Piledriver

Note:

The casualties for the 65th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division primarily resulted from combat with the 15th Corps of the Chinese Volunteers at Chipori.

From May 23 to June 1, the 65th Corps bore the brunt of the fighting against coalition forces, with some casualties from the 1st Cavalry Division stemming from these engagements.

In summary, the coalition forces sustained a maximum of about 1,500 casualties in their battles with the 63rd Corps in the Yeoncheon and Cheorwon regions.

What Delayed the U.S. Occupation of Cheorwon: Weather or the Heroic Resistance of the Volunteers?

The U.S. military was a mechanized force, and weather conditions and road conditions significantly affected their offensive capabilities. Let’s examine the weather reports and casualty statistics from the Eighth Army over these critical days:

May 28: Heavy rain. The U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 65th Regiment and the 1st Cavalry Division’s 7th Regiment each reported 1 KIA.

May 29: Heavy rain. The U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 15th Regiment reported 1 fatality, and the 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 5 fatalities.

May 30: Heavy rain. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 5 fatalities; the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division reported no loss.

May 31: Heavy rain. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 8 fatalities, the 8th Regiment 1 fatality, and the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 7th Regiment 3 fatalities.

June 1: The rain stopped and the weather turned clear. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 3 fatalities; the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division reported no loss.

June 2: Clear weather. The 1st Cavalry Division’s headquarters reported 1 KIA, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 7th Regiment reported 5 fatalities, and the divisional medical unit reported 1 death.

June 3: Heavy rain. The battle for Cheorwon commenced: the 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 5 KIAs, the 7th Regiment 5 fatalities, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 65th Regiment 15 killed, and the flanking 7th Regiment 8 killed.

June 4: Heavy rain. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 4 fatalities, the 7th Regiment 5 fatalities, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 65th Regiment 27 KIAs, and the 15th Regiment 1 fatality, as they broke through the first line of the 63rd Corps.

June 5: Heavy rain. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 5 fatalities, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 65th Regiment 6 deaths, the 7th Regiment 1 fatality, and the 15th Regiment 1 fatality; the attached U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 10th Combat Engineer Battalion reported 1 KIA.

June 6: Weather cleared. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 7 fatalities, the 7th Regiment 4 killed, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 65th Regiment 2 fatalities, and the 7th Regiment 3 fatalities.

June 7: Clear weather. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 5th Regiment reported 5 fatalities, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 7th Regiment 6 killed, and the 15th Regiment 7 killed.

June 8: Clear weather. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 7th Regiment reported 2 fatalities, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 7th Regiment 4 fatalities, as the PVA began to withdraw in scattered formations.

June 9: Clear weather. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 7th Regiment reported 2 KIAs, the 8th Regiment 1 KIA, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 15th Regiment 1 fatality, and the PVA withdrew unit by unit.

June 10: Clear weather. The 1st Cavalry Division’s 7th Regiment reported 1 KIA, and the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 7th Regiment 1 fatality. The battle concluded.

June 11: Clear weather. The U.S. 3rd Infantry Division’s 15th Regiment and the attached Philippine battalion entered the city of Cheorwon.

The only mention of the impact of heavy rain on the Cheorwon resistance from the Chinese sources came from the diary of Cai Changyuan, the commander of the former 189th Division of the 63rd Corps. His division faced severe casualties on the front lines and had been reduced to five battalions. The torrential rains caused flash floods that inundated the troop shelters and hiding places dug into the hillside, prompting Cai to furiously criticize the meteorological department. Although Cai did not explicitly detail the floods’ effects on his division, he revealed a horrifying truth: the 189th Division had entered Korea with 14,000 men. By the evening of June 3, they still had 5 battalions (over 4,500 men) left, but after the torrential rains of June 4, only 2,800 remained. This indicated that over 1,700 men had perished due to floods drowning their shelters, and a deputy commander from the 562nd Regiment drowned. Consequently, the unit was forced to abandon their front-line positions and withdraw, replacing themselves with the reserve 188th Division.

The Battle of Cheorwon for the 63rd Corps was essentially a military “delay operation,” aimed at prolonging the enemy’s actions. This mirrors how the 63rd Corps was delayed for over 50 hours by the British Gloucester Regiment at the banks of the Imjin River just a month prior. The outcome of such tactics resulted in significant losses; as the defending side, they could not inflict substantial damage on the enemy. In comparison to other significant battles in the Korean War, the casualties in this battle (around 170 KIA) do not rank among the top twenty in terms of losses. The 63rd Corps’s ability to delay the U.S. forces for 13 days was critically influenced by weather factors during the conflict.

PVA losses in the battle

Unfortunately, the extent of the fatalities sustained by the 63rd Corps during the Battle of Cheorwon remains a mystery. Unlike the U.S., which meticulously recorded daily casualties for every unit, China’s military historical archives have been less precise, often opting for vague language and obscured details.

Many veterans of the 63rd Corps, seasoned from previous battles, managed to withdraw swiftly after the Spring Offensive’s defeat, preserving most of their strength. However, post-Cheorwon, fewer than 3,000 troops remained, and even the commander, Fu Chongbi, was injured, indicating a significant weakening of their combat capacity.

Based on Peng Dehuai’s post-battle promise to Fu Chongbi to replenish the division with 20,000 troops, it is estimated that the irreversible losses of the 63rd Corps (including fatalities and serious injuries leading to disabilities) were no less than 20,000—this figure does not account for the losses incurred by the 65th Corps’s 194th Division or the temporary reinforcements from the 19th Corps deployed before the battle.

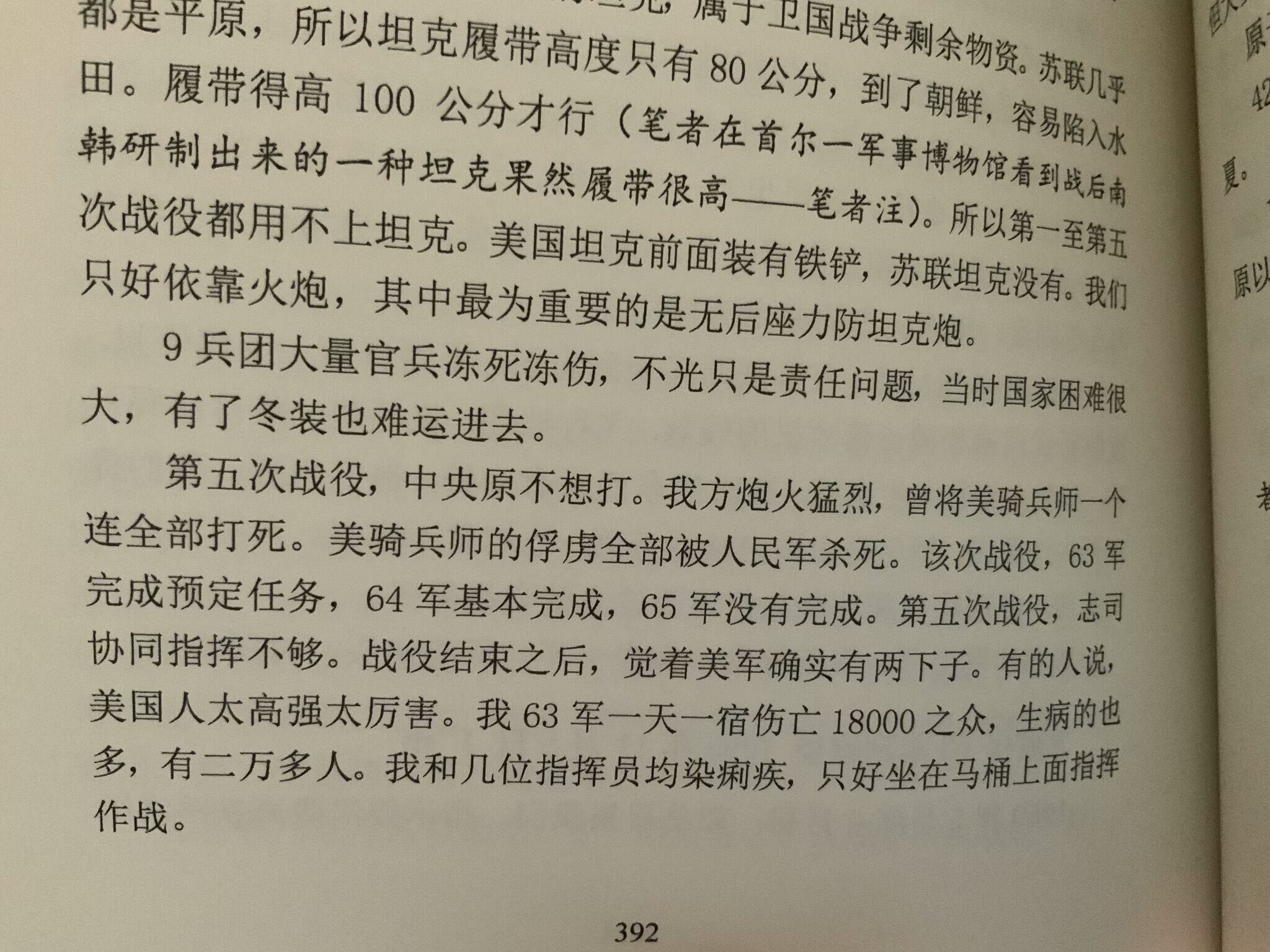

In his memoir, the political commissar of the 63rd Corps stated that the troops suffered 18,000 casualties during a single day and night of battle. Additionally, 20,000 soldiers fell ill, including himself; he was forced to command the battle from a toilet.

On May 26, 1951, Peng Dehuai sent a telegram on behalf of the Volunteer Army’s leadership to Mao Zedong, discussing the difficulties and issues present at the front lines: “Certain cadres have developed serious rightist sentiments, failing to carry out or even defying orders.” There was a growing weariness with the prolonged nature of the war and concerns that future operations would become increasingly difficult, leading to doubts about the possibility of victory. Some cadres even disobeyed commands, resulting in abnormal relations between officers and soldiers and a severe breakdown of discipline. On June 3, the very first day of the UN forces’ attack, Mao Zedong and Kim Il-sung made a request to Stalin, asking the Soviet government to initiate ceasefire negotiations with the UN forces. On June 13, Stalin finally approved the request for ceasefire talks from Mao and Kim.

After the battle, the remnants of the 63rd Corps retreated to Yichuan. Along the way, they happened upon a unit from the 65th Corps cooking dumplings by the roadside. In a fit of anger, the disgruntled soldiers from the 63rd Corps kicked over the pot of dumplings, nearly escalating the situation into violence between the two groups.

On March 28, 2014, the South Korean government handed over the first batch of 437 remains of Volunteer Army soldiers to China. These remains were excavated from the areas around Yeoncheon, Paju, and Cheorwon, which were the sites of the 63rd Corps’ “delay operations.” It is possible that these buried remains include those of individuals who perished in the flooded tunnels during that catastrophic rainstorm.

In fact, the 26th Corps of the Volunteer Army fought a nearly identical delaying action against the U.S. 25th and 7th Divisions in Kimhwa. However, the 26th Corps was less boastful and chose not to exaggerate their battle into victories, which is why the battle of Kimhwa remains relatively obscure.

References:

(1) I Corps Command Report Narrative, May 1951; IX Corps Command Report Narrative, May 1951; Weather Effects on Army Operations: Weather in the Korean Conflict, Vol. II, Chapter XIV: Operation Piledriver.

(2) United States Army in the Korean War: Ebb and Flow, November 1950 - July 1951. Billy C. Mossman, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, DC, 1990.

(3) Truce Tent and Fighting Front, Walter G. Hermes, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, DC, 1992.