The Longest Siege , Tobruk - Robert Lyman

Tobruk The Great Siege 1941-1942 - William Buckingham

Tobruk - Peter Fitzsimmons

Desert Boys - Peter Rees

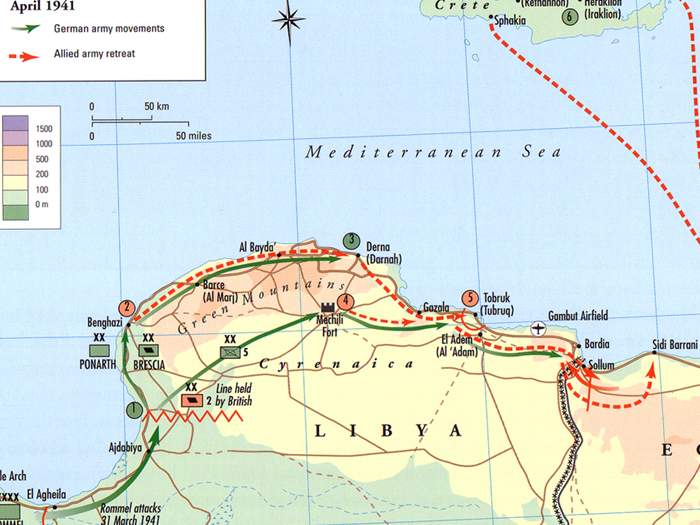

When Rommel with his one German division and extra few units opened up his suprise offensive , in a few days German Italian Panzer Group (as titled back then) recaptured almost all of Cyreneica in a few days. Inexperienced and badly deployed equipped 2nd Brtitish Armored Division was mauled up by fast moving strikes of German forces at Merselbraga (31 March) , Agadebhia (2 April) , Msus (4 April) and Mechilli (7 April , this is where most of the command headquarters and rear echalon of entire 2nd Armored Division was captured and Rommel got hold of British booty “Mammoth” command vehicles he would use during entire campaign in desert.) Even worse architecht of previous British victories in North Africa General O’Connor was also captured close to Derna on 7th April along with front commander General Neame. Benghazi was recaptured by German troops on 5th April. It seems like with arrival of one young German general , entire outlook of North African Campaign changed and Egypt again seemed under threat of Axis.

With Mechili seized on 7th April , Rommel ordered General Johannes Streich commander of 5th Light Division (later conversed to 21st Panzer Division) to strike east to the coast without delay. Speed had achieved the capture of Cyrenaica, and Rommel was insistent that the same relentless pace be carried on to complete the capture of Tobruk. While the 5th Light Division was pressing overland through Cyrenaica, the coastal advance had made rapid progress, and Derna had been captured on 8 April by motorcycle battalion of Oberst Ponath supported by combat teams led by Oberst Schwerin and Oberst Olbrich rushed up from Mechili. At the same time Tripoli had seen the arrival of General Heinrich von Prittwitz’s 15th Panzer Division, with troops flying directly into Benghazi. Within the month they would also be flying into Derna.

Rommel recognized early on just how vital Tobruk would be to his advance into Egypt. In British hands it would prove a constant sore in his flank, as well as denying him the use of its port for supplies and reinforcements. Rommel was therefore concerned to overrun it as quickly as possible before its defences could be organized.

Late on the evening of 8 April Rommel reached the sea at Derna only hours after the retreating Australians, the 2nd Division Support Group and the tank-less remnants of the 3rd Armoured Brigade had managed to extricate themselves from the town, although large numbers of other troops and equipment fell into German hands. Oberst Ponath scribbled quickly in his diary that night:

Unit advances on Derna. No enemy. Odd POWs keep arriving. A heavy sandstorm is blowing up. A German aircraft lands and makes contact and takes the mail. Derna is clear of the enemy. Brescia Division approaches from the west. Order to move to Tobruk [arrives] at 2100 hours. Rommel is pleased with our success. Dead tired. Night march. Handing over of prisoners and captured material.

Details of the Tobruk defences were as yet unknown to the Germans. They had no maps and no idea of what they faced. But given the rapid advances his troops had already made, Rommel could not believe that he would meet anything other than mild resistance. He had seen nothing over the last few days to make him believe that Tobruk would be anything other than a walkover. On 9 April he received reports of activity in the town, including (unformirmed lately proved to be false) news that the British were attempting a Dunkirk-type evacuation from the harbour, and that same day the Italian Brescia Division arrived after its advance along the coast road from Benghazi. Like the dash across Cyrenaica,

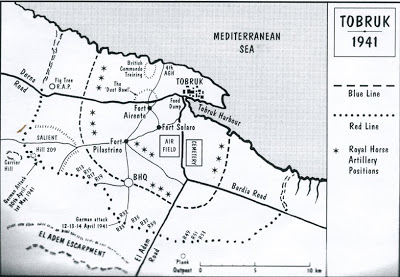

and entirely in keeping with Rommel’s character, Rommel’s first plan to take Tobruk depended on speed and surprise. He ordered an immediate assault. The Brescia would advance from the west, raising a great cloud of sand to confuse the enemy into overestimating Axis strength and intentions. At the same time Streich’s 5th Light Division would sweep around the southern perimeter to attack it from the south-east, while recently arrived General Heinrich Von Prittwitz (whose 15th Panzer Division was still incoming to Benghazi by sea and air and organising) would assault the town directly from the Derna Road.

Rommel had assumed that Streich would by this time have joined him on the coast, but the 5th Light Division was dismantling and repairing the turrets of its tanks, jammed shut by the sand, at Mechili. Rommel was furious with the delay and ordered Streich to Gazala by the next morning, Thursday 10 April, from which point he was to attack Tobruk. In the afternoon Rommel moved east to Tmimi, and informed General Von Prittwitz of his plan. Given command of the 3rd Reconnaissance, 8th Machine-Gun and 605th Anti-Tank Battalions, Prittwitz was ordered on the evening of 8 April to drive on to Tobruk without delay. Having only just arrived from Benghazi, Prittwitz was staggered. ‘But I’ve only just arrived in Africa,’ he complained to Lieutenant Colonel von Schwerin. ‘I don’t know the first thing about the troops or the terrain.’ Schwerin found him a bed, and the exhausted Prittwitz fell asleep only to be shouted awake by Rommel at dawn next morning on 9th April . ‘The British are escaping!’ A confused, disorientated Prittwitz leapt into Schwerin’s Kubelwagen and sped towards Tobruk.

General Von Prittwitz , the general Rommel caused his death

On the same morning Major General Heinrich Kirchheim, in temporary command of the Italian Brescia Division, was ordered by Rommel to find a suitable area to prepare his division to attack Tobruk. On the Derna road Kirchheim suddenly saw sand kicked up on the road ahead. ‘Aircraft!’ shouted his driver as three Hurricanes approached at speed just above the desert. Machine-gun fire engulfed the vehicle and Kirchheim was struck in the arm, shoulder and eye. As Kirchheim’s wounds were being dressed, Prittwitz arrived on the scene. After exchanging pleasantries – Prittwitz congratulating Kirchheim on wounds that would send him home – Prittwitz drove on towards Tobruk.

Ponath’s forwardmost troops had been held up eleven miles short of Tobruk on the Derna road by intense artillery fire from the guns of the British 51st Field Regiment and Australian anti-tank guns, some of them siezed Italian weapons. It was into this hail of fire that the unfortunate Prittwitz, with Schwerin’s driver, drove on the morning of 10 April. At Milestone 13 a direct hit from an Australian anti-tank gun killed them both. Streich – whom Rommel had sidelined for the attack that morning in favour of Prittwitz because he believed the former slow and conventional – was furious at what he regarded as Prittwitz’s unnecessary death and laid the blame squarely on Rommel’s shoulders, a result of his arrogant impetuosity.

Thirty-one-year-old Captain Vernon Northwood of A Company, 2/28th Australian Battalion (from recently arrived 9th Australian Division which was deployed to Tobruk literally hours ago , mostly via sea by fast ships from Alexandria) watched the first German troops come unwarily into his sights. The Australians – individual toughness and raw courage making up for what they lacked in battlefield experience – saw no reason why they should be ‘frightened of Jerry’ and were grimly determined to hold the line come what may.

“On the first day, 10 April, ten o’clock in the morning, we saw the German tanks coming over the rise. The Royal Horse Artillery were firing over open sights, but they copped an awful bashing from the tanks. We could hear men screaming. They carried them to a bit of a ditch. I was up a water tower, with a wonderful view, so I was able to report back what I was seeing. I was cold with fury when I saw the Germans machine-gunning an ambulance as it came up to get these fellers. Our men just took it in their stride though. Many of them had worked in the goldfields [of Western Australia]; they were men who knew what rough living was all about.”

Private Peter Salmon, also of the 2/28th Battalion, was surprised by the nonchalance of the advancing Germans. They clearly believed Tobruk would be a walkover:

“I was on the Derna Road when the Germans came. I remember it very vividly – it was a surprise to see them. They were in trucks and they came to the perimeter and I still see them getting off those trucks. I don’t know what they expected to find, but then of course we opened up on them with small arms and artillery – the blokes that were using the bush artillery were quite incredible, because they had no sights (the Italians had stripped the guns of their sights) but they were getting some very accurate firing, and it was amazing what they did.”

The ‘bush artillery’ comprised Australian soldiers manning siezed Italian artillery pieces. The stripped sights proved no impediment to the Diggers, who were assisted in their efforts by the vast quantities of ammunition left behind in Tobruk fortress. John Devine came across guns and men of the bush artillery on the El Adem road only yards short of the Red Line:

“This particular lot of bush artillery was operated by a mixed crew of batmen and cooks . . . they had their OP [observation post] fully twenty yards in front of them at the roadside . . . The OP would take up position, and after the shell had been pushed into place in the spout, and the fuse had been wrenched to the desired time setting with the aid of a spanner from the truck [which had brought up the ammunition], there followed little bags containing Italian cordite. These were pushed in after the shell in no very definite quantities, and finally the breech was rammed home. The gunners then retreated down a very long rope lanyard . . . This lanyard then being pulled, fired the gun. The burst was watched, and the OP signalled the result of the shot. A typical signal following observation of a burst would be ‘Move her two telegraph poles to the right. Knock out a bloody brick.’ Traverse was measured in telegraph poles along the road, and to vary the elevation bricks were pushed under the trailer.”

Italian bush artillery in British and Australian service

The bush artillery did not claim to achieve much more than raise the morale of the troops, although Devine records that the amateur gunners claimed many Italian trucks and a stationary aeroplane that had been forced to land beyond the wire. Private Frank Harrison spoke with real affection about these untrained but determined Australians sighting their guns by squinting along the barrel and shouting ‘Let 'er go, mate!’ at the required moment.

If improvised, the defensive block was nevertheless extremely effective, and the death of Prittwitz dealt the overconfident Germans a significant blow. On the same day Rommel’s party (including Schmidt) in its newly acquired Mammoth came under accurate British artillery fire from El Adem, which the British evacuated later in the day, when the 7th Armoured Division Support Group withdrew back into Egypt. Von Wechmar’s 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion then moved through Acroma and across the desert tracks south of Tobruk to El Adem. At one stage Rommel noticed two vehicles following the Mammoth, one of which was clearly British. Ordering his men to stop and train an anti-tank gun on the pursuing cars, he was surprised to be confronted by a red-faced Streich, yelling at him that his actions had cost Prittwitz’s life. Rommel was unmoved. ‘How dare you drive after me in a British car? I was about to have the gun open fire on you.’ Streich retorted, ‘In that case, you would have managed to kill both your panzer division commanders in one day, Herr General !. ’