The Desert War “1940-1943” Alan Moorehead (war correspondent)

The country the men were asked to penetrate after Tobruk was vastly different from the desert. Derna was an oasis of banana plantations and pomegranate groves, of lush vegetable gardens and leafy trees. Beyond, in Jebel Akhdar (Green Mountains) , you might have thought you were on the Yorkshire moors. A fresh mountain wind blew and with it came heavy rain and hailstones. The reddish-brown earth undulated into green valleys and hilltops dotted with shepherds’ flocks and neat white colonial homesteads, all built to the same standardised pattern, all modern, all surrounded with neat hedges and home gardens. The villages were trim, hygienic and attractive—if your taste runs to ordered rows of white cottages and streamlined town halls and sewerage works. All this was a great change from the desert. It relieved us of the problem of water and presented us with another difficulty—mud. . .red, clinging, loamy mud that frothed up round the axles of the cars and sent them skidding round in the opposite direction to the one in which they were going; mud that bogged tanks and stained the men up to their waists; mud that got into your food and your eyes and your hair; mud that was cold and very very dirty.

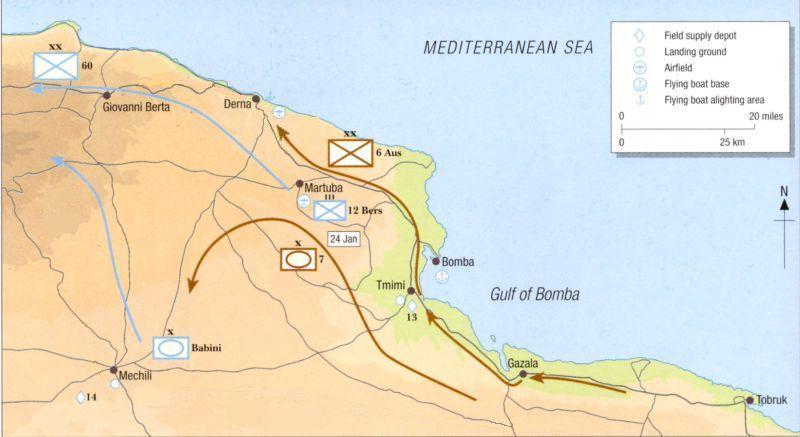

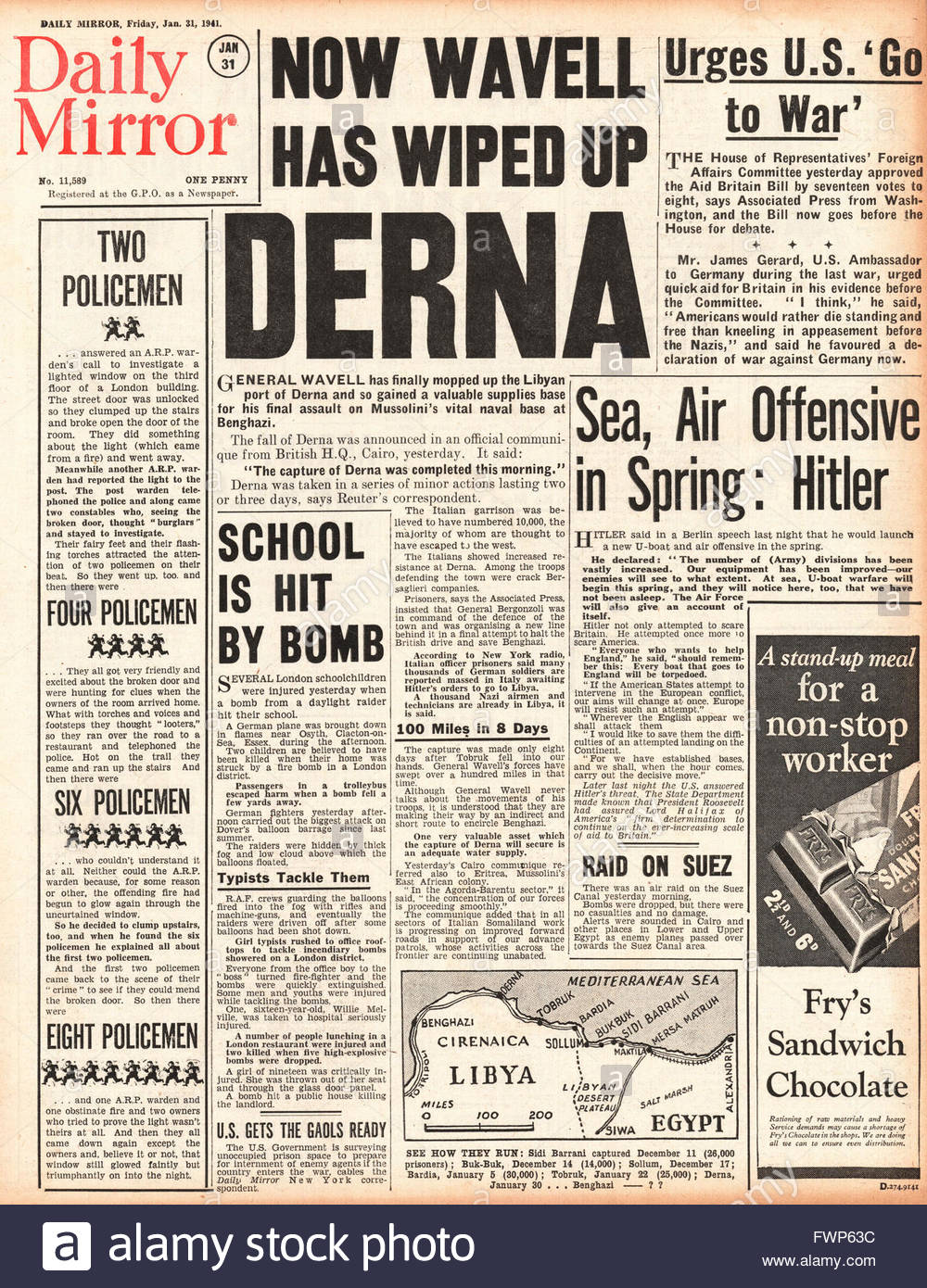

But the first hundred miles were the best. In fair weather we rode on past Bomba toward Derna on a perfect road. Little by little the scattered bushes grew to shrubs and even at last to clumps of trees and a few palm groves. Bomba fell easily. But on Derna aerodrome, a great red plain lying above the thousand-foot sea cliffs with the town below, the Italians stood and fought. Wadi Derna, a ragged valley that struck into the hills, was for a few days death to enter. A few companies of Australians charged the aerodrome above with the bayonet and made themselves masters of its storehouses and buildings. The two sides were so mingled at first that the leading Australian platoon lodging in a hangar heard Italian voices through the night. In the first light of morning they saw, not three hundred yards away, four Italian tanks. The tank crews were cooking breakfast. Scarcely daring to breathe, the Australians whispered urgently down their field telephone for anti-tank guns, and the Italians were blown up before they finished breakfast.

The aerodrome with its twenty wrecked Italian machines (planes) was now ours, but unexpectedly about forty Italian guns firing from the other side of Wadi Derna turned upon it an uninterrupted cannonade of shellfire. The shells kept bursting and bursting as though they would never stop. I crouched beneath the flimsy protection of a hangar door, with a Libyan prisoner who kept saying to me:

I don’t want to stay here. I’ve surrendered. Why don’t they take me back behind the lines?’

What does he say?’ asked the Australian sergeant.

‘He says he doesn’t like it,’ I translated.

‘Tell him we don’t like it either,’ said the Australian sergeant. I told him. ‘Then,’ the Libyan protested, ‘why don’t we all go back?’ It did seem at that time a first-class idea.

This was a bad shelling while it lasted. And it lasted three or four days. The Italians had every building on the aerodrome registered, and the buildings were the only cover. One evening they shelled a platoon of Australians back from the open into the administrative block; then they hit the block and shelled the Australians out the back door and up the hillock behind. Once again the Italians got onto them, and the Australians were pursued with a chain of bursting shellfire across the aerodrome into another building and out of that.

Watching from only four hundred yards away, where it was quite safe, that incident seemed funny to the rest of us. I do not think it is funny now, but it was then, at a moment when one was keyed to meet the tension at the front and the small manners of living were diminished or forgotten entirely. One lived there exactly and economically and straightly, depending greatly on one’s companions in a world that was all black or white, or perhaps death instead of living. Most of the things it takes you a long time to do in peace-time—to shave and get up in the morning, for example—are done with marvellous skill and economy of effort at the front. Little things like an unexpected drink become great pleasures, and other things which one might have thought important become suddenly irrelevant or foolish. In a hunter’s or a killer’s world there are sleep and food and warmth and the chase and the memory of women and not much else. Emotions are reduced to anger and fear and perhaps a few other things, but mostly anger and fear, tempered sometimes with a little gratitude. If a man offers you a drink in a city bar, the offering is little and the drink still less. You appreciate the offering and often give it more importance than the drink. At the front the drink is everything and the offering merely a mechanical thing. It is never a gesture, but a straight practical move as part of a scheme of giving and receiving. The soldier gives if he can and receives if he can’t. There is no other way to live. A pity this is apparent and imperative only in the neighbourhood of death.

We would spend the day at the observation post of our sixty-pounder guns that were demolishing the enemy batteries one by one, and return to our lodgings in a deserted garage on the aerodrome at night. It was exposed and under fire, but the walls were fairly solid and the Italians did not seem to be interested in it. One night while the blitz was on we achieved, in honour of the artillery major and his captain, a dinner of wine, vegetable stew, sauce, fruit, tea and brandy—a rare meal at that time.

The fall of Derna depended greatly upon the fall of a certain Fort Rudero, which the Italians were using as an observation and sniping post. In the first advance one Australian company was all but wiped out trying to take it from the seaward side, and another company attacking it from the wadi inland had to be withdrawn. The final attempt came one forenoon, when the red earth was washed and new after a heavy shower at night. The barrage had begun afresh, and a staid slow fight of Savoias—the last we were to see—had been over bombing until it ran into a lone Hurricane coming back from patrol into Libya. The Australians forgot the shelling, forgot momentarily the wounded nearby and their hunger, and raised a cheer as the Hurricane dived straight through the Italian machines and sent one dropping with that breathtaking fateful slowness to the red desert. Its bursting flames rose from behind the wreckage of the other broken aircraft on the field.

The Italian shells were falling twenty and thirty yards away from us, tearing off bits of the hangar, blasting our eardrums and raising billows of red dust from the quickly drying earth. Through the noise and blast another Australian company advanced toward us—dark little figures marching slowly with heads down in little lines across the open airfield. ‘Good troops,’ the brigadier had been saying back at brigade headquarters, just before this engagement, ‘will never be stopped by shelling.’ Yet this was hard. The Italian artillery observers could actually see them. The little lines drew level with the hangar and passed on up to the ridge beyond which no one had yet advanced. For a moment I watched them pause in the full face of the enemy shelling on the open crest of the ridge and then they disappeared over the top of it. By the time I had crawled up to the ridge in a lull in the firing they had crossed the valley to the next rise, the one that ran straight down into Derna only three miles away.

I joined a British Vickers-gun unit that was shooting the Italian positions just ahead of the advancing Australians. The British sighted first on an enemy observation post, silenced it, and then turned their fire on some trucks. My ridge and the ridge on which the Australians were advancing lay parallel. The intervening valley was filled with Italian shellfire. We gave it an hour or two and then followed. It seemed certain that Fort Rudero, the objective, had fallen. We went on foot, taking a wide sweep round to the right away from the Italian positions, and came up under the fort with a party of Australian water-carriers.

Fort Rudero had not fallen, but there was something strange and quiet about the place. After the heavy fighting along the beach yesterday its guns had not spoken. We were clinging now to the side of a cliff so precipitous that it was not easy to stand upright, and the soldiers in this sector had been here twenty-four hours without food or water. As soon as they had eaten, the company was ordered forward to take the fort. We clambered first onto a pinnacle of the cliff where all Derna broke suddenly into view, a thousand feet below. . .the most startlingly pleasant sight one could conceive after so long a time in the desert. We were looking right into the town as from an aeroplane. Row after row of stout, snow-white houses reached down to the graceful sky-blue harbour. A steamer, bombed by the R.A.F. and fired by the Italians, lay sinking at the jetty. Close by rose a high modernistic hotel and beyond that was the main street leading to the lighthouse. One or two cars were going along this street. A few people were moving in front of the shops. A great grove of spreading palms made a cool green pool of colour in the centre of the town.

While we gazed down, the Australian riflemen had gone ahead through the barbed wire and surrounded Fort Rudero, a rough stone pile perhaps five hundred yards square. No sign of the enemy appeared and the soldiers relaxed a little. Some of them made in a bunch toward the side door. Once more then the enemy had vanished in the night. Concerned that he would miss a good picture, an officer with me, who was taking photographs for the War Office, called the men back and asked them to re-enact their passage through the barbed wire. Readily the men agreed. Twice the photographer rehearsed them through it, and then, the pictures taken, we all went up to the fort together to see what the enemy had left behind.

It was full of Italians. While we had posed for photographs fifty yards away outside, they had stood there with their rifles waiting dumbly to surrender. They lurked in the cellars and the stone passages; they stood in the central courtyard surrounded by the wreckage of our shell-bursts. They smoked, they stood packing their kits, or kneeling to get a last drink of water from a broken wooden barrel.

The Australians, recovering from their surprise, presented their bayonets and ran through every room and dugout until the prisoners were herded together in the main courtyard. They even unearthed a couple of white puppies born just before the bombardment began. Revolvers were grabbed from the Italian officers and rifles from their men. It was all done very quickly, and soon a platoon was on its way down the other side of the ridge to silence an Italian machine-gun post that was still pinging spasmodically up the hill. Farther back, six hundred yards away, I could still see odd groups of Italians on the run, but suddenly our artillery got onto them and they disappeared in clouds of blown dust and rock.

Three of us—the photographer and two war correspondents—were asked to escort the three senior Italian officers back to our own lines. The Italian major was obviously overstrained and tired. He leaned heavily on his dignity. The junior lieutenant, scarcely more than a boy, had wept under the machine-gun fire and again when he had asked me whether he would be shot out of hand or later. (It was a lie deliberately fostered by the Fascist command that Australians took no prisoners.) So then the six of us—the three Italian officers and we three—set off together afoot. The major was so confused he led us straight onto a field of Italian landmines and we circled back to the main road just in time.

I was beginning to chat freely with Tenente (Lieutenant) Alberto Pugliese, a lawyer from Rome, when a round of machine-gun bullets tore through the space between us. I was the first to hit the ditch beside the road, with the tenente on top of me, and there we lay while the bullets ripped up the road a foot away. Clearly the Italian snipers had that spot marked. Every time we raised our heads bullets started spurting past again.

‘It’s your machine-gun,’ Pugliese said.

‘It’s not,’ I said.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘I’ll stand up, and if they don’t fire when they see my uniform, we’ll know it’s Italian and I’ll ask them to stop. If they do fire, we’ll know it’s British. Then you stand up and ask them to stop.’

I looked at him hard, but he was apparently serious. ‘You stay right where you are,’ I told him coldly. Not for anyone on earth was I going to stand up. My further embarrassment was saved by the arrival of an Australian officer who called us to come on. We ran for it then until we had cover and were behind our own lines. Pugliese and the others went off toward the rear by truck with their two fox-terriers, Tobruk and Derna (Bardia, their third dog, had been killed).

These officers were typical Italians, voluble and assertive once they were certain no reprisals were going to be taken upon them. Pugliese had argued with me in the ditch: ‘We would have gone on shooting, but where was the point when your guns are twice as good as ours? Anyway, we could not have gone back to Italy after this failure. As for Italy—well then, if what you say is true and the Germans are taking over the country, then good, the farce is over. But don’t think there will be revolution (against Fascism in Italy) yet. There are many like me who have got nothing out of Fascism, but we don’t dislike it enough to rebel against it. Even if we hated it, what could we do about it?’

Yes, what could they do? The machine had started turning and only exhaustion now would stop it. They could surrender to us. But never to themselves.