from

“The Longest Siege : Tobruk” written by Robert Lyman

wikipedia

Time Life - World War II , “War in the Desert”

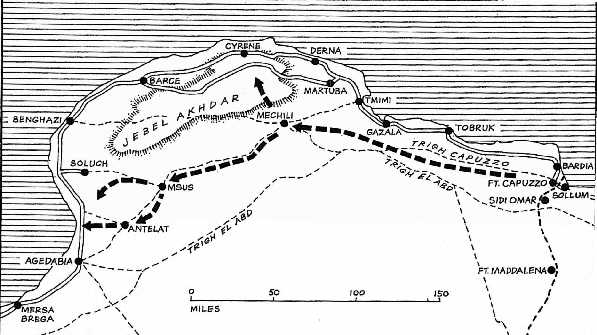

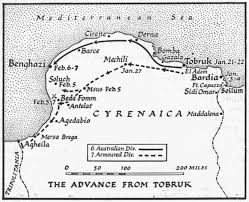

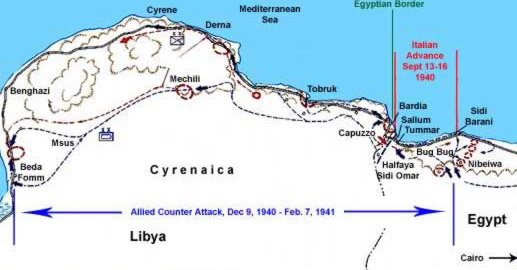

By early February it was clear to 13th Corps commander General O’Connor that Italian Marshal Graziani was not merely pulling back in the east, but was preparing to withdraw his forces from Cyrenaica entirely. This assessment offered O’Connor a brand new opportunity: despite the exhaustion of his troops, the heavy wear on his tanks and vehicles and the bitter cold of the wet desert winter, an audacious move now might enable him to destroy Graziani entirely. As the crow flew, the distance between Mechili and the coast south of Benghazi on the Gulf of Sirte was a mere 150 miles, cutting across the desert south of the Jebel Akhdar. The route, however, was unmapped and unreconnoitred but known to be rough, waterless desert. While the Australian 6th Division pushed hard against the Italians in the north along the coast, O’Connor determined, with Wavell’s blessing, to send what was left of the 7th Armoured Division by this route to cut the road south of Benghazi and destroy the remainder of General Tellera’s 10th Italian Army as it attempted to flee into Tripolitania.

O’Connor had hoped that he might be given two weeks to resupply his exhausted 13th Corps (the Western Desert Force had changed its name on 1 January) before continuing his advance. The 7th Armoured Division was by now reduced to about forty cruisers and eighty light tanks, all of which were in a poor state of repair. It was clear by Monday 3 February, however, when the Australians discovered the ancient Greek and Roman town of Cyrene (latterly Graziani’s Cyrenaican headquarters) evacuated, and Barce further to the west also abandoned, and RAF air reconnisance indicating that Graziani was beginning a full-scale withdrawal from Cyrenaica. This forced O’Connor to act immediately with what he had to hand. Accordingly, he ordered an immediate reconfiguring of his forces. His desert thrust comprised a group of some 2,000 men based around the newly reinforced 4th Armoured Brigade (3rd and 7th Hussars and 2nd RTR) with two squadrons of the 11th Hussars and a squadron of armoured cars from the newly arrived King’s Dragoon Guards; the infantrymen of the 2nd Rifle Brigade in trucks; the 25-pounders of the 4th RHA and a battery of 2-pounder anti-tank guns of 106th RHA. Each tank was loaded with two days’ worth of rations and water, and topped up with ammunition and fuel.

The advance across the uncharted desert from Mechili began at dawn on 4 February. The terrain was littered with rocks and large boulders, and the tanks had to pick their way carefully to avoid throwing tracks or otherwise damaging the vehicles. Ordinarily the armour would have stopped at last light to leaguer but on this occasion, as speed was imperative, the advance continued in the moonlight. ‘It was bitterly cold,’ Cyril Joly recalled, ‘*so that my face soon became frozen and raw and was painful to touch.’ *

Occasionally I glanced down into the turret to reassure myself that I was not dreaming the whole situation. In the eerie light cast by the single red warning bulb of the wireless set I could see, beyond the glinting metal of the gun breech, the huddled figure of Tilden. At my feet, crouched forward peering through the gun telescope – his only view of the outside world – sat Holten, on the alert . . *.Beyond, and further down and forward, I could see Syke’s head and shoulders silhouetted against the panel and instrument lights on the forward armoured bulkhead.

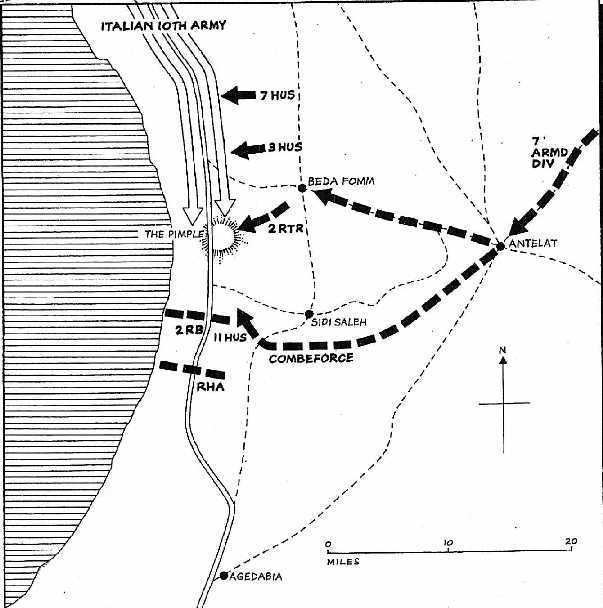

Stopping in the dark cold at about 1 a.m. some distance short of Msus, the division was ready to depart again at first light on Tuesday 5 February. Because of the slowness of the tanks and the urgency of getting to the coast road before the retreating Italians it was decided to divide the force into two groups. The faster, under Lieutenant Colonel John Combe of the 11th Hussars, set off with all haste. Combeforce comprised two squadrons of the 11th Hussars, the 2nd Rifle Brigade in Bren gun carriers and trucks, and two batteries of 25-pounders. (this hastily gathered advance units nicknamed Combeforce) Behind, advancing more slowly, came the remainder of the 4th Armoured Brigade, with the understrength 7th Armoured Brigade and the rest of the support group bringing up the rear. Broken-down trucks and tanks littered the route. ‘My God,’ O’Connor said nervously on seeing yet another abandoned vehicle as he followed. ‘Do you think it’s going to be all right?’

It was. With their last drops of petrol Combeforce struck the coast road near Sidi Saleh about noon ten miles south of Beda Fomm, the road dominated by a rise to the north – nicknamed the ‘Pimple’ by the troops – and a white mosque to the east on 5th February. The 2nd Rifle Brigade immediately deployed in a thin screen of rifles, machine guns and 2-pounder anti-tank guns between the road and the sea, dug in among the undulations of the sand and rock, behind which, nearly half a mile to the rear, were placed the guns of 4th RHA. The old armoured cars of the 11th Hussars and Kings Dragoon Guards found fire positions as best they could. The few anti-tank mines they had were placed on and astride the road. Almost immediately battle was joined. At 2.30 p.m. the front end of a vast convoy of retreating Italians stretching as far as the eye could see encountered British road block. The road erupted in sheets of flame and billowing smoke as the first shells found their mark, and the Rifle Brigade’s machine guns began to chatter.

The British force was a rude shock to the Italians, many hundreds of whom were base and support staff and civilians being escorted to safety away from the rapidly approaching Australian threat to the north. Graziani had known that the British were attempting to strike through the desert but had no notion that the threat was of a scale sufficient to take on the remainder of the entire 10th Army. For the rest of the afternoon the Italians fought desperately to find a way through, but despite the rapidly diminishing British stocks of ammunition, could find no way to do so. In the late afternoon the three armoured regiments of 4th Armoured Brigade, which had been picking their way slowly forward through rocks and Italian Thermos bombs, finally arrived in the sand dunes on the eastern flank of the road some miles to the north. The eager tanks of the 7th Hussars hurtled into the masses of Italian transport lining the road, driving at speed along the flanks of the stricken column while, with turrets traversed, their guns spewed fire.

No Italian tanks were yet on the scene as dusk settled over the battlefield, and a quiet of sorts allowed the British positions to be reinforced and resupplied, while broken-down and redundant vehicles were drained of their fuel for the tanks. British Bren gun carrier patrols worked the Italian flanks through the night, during which the first muted sounds of arriving Italian armour could be heard. The British plan for the continued defence of the block on 6 February was to allow the 4th Armoured Brigade to eat into the Italian flank while awaiting the arrival to the north later that day of the 7th Armoured Brigade and the support group.

The plan worked perfectly, but the day was not without its worrying moments, as Italian pressure remained heavy and the British supply situation became precarious, with fuel just about exhausted and ammunition rapidly dwindling. As dawn on 6 February allowed the first struggling rays of light onto the wet and windy battlefield, gradually bringing to view the smoky hulks from the previous day’s fighting, 2nd RTR arrived short of the Pimple in the vicinity of the white mosque after spending the night leaguered in the desert. Captain Cyril Joly was not prepared for what he would find:

As my tank came to the top of a ridge about two miles east of the road I was staggered by the amazing scene before me. South, to my left, I could see the puffs of the shell-bursts on the brilliant white dunes which marked the positions of the blocking force. From there, and directly in front of me and to my right, stretching as far as the eye could see, the main road and the flat ground on each side of it were packed tight with every conceivable type of enemy vehicle and equipment.

The 2nd RTR tanks moved quietly into hull-down positions 2,000 yards from the road, unseen by the enemy. After hurried orders, the regiment, with only nineteen operational tanks, attacked, Cyril Joly’s troop stationary and hull down in the middle acting as a pivot to the remainder. The cruisers advanced against the huddled mass of Italians, firing as they went. The enemy responded immediately and aggressively: ‘Twenty Italian tanks which had been moving down the east side of the road to join the vanguard attacking the blocking position wheeled left at once and engaged. The first sounds of machine-gun fire and the crack of the high-velocity tank guns turned the attention of the Italian gunners to this new menace. In a matter of moments they too had switched to engage the new targets.’ These were Babini Mechanised Group tanks which engaged British and Australian forces in Derna anbd Mechili two weeks ago. Italian tankers were brave but they made a huge mistake of attacking British armor positions without air or ground reconnicance , almost blindly without any idea what is before them.

Despite their efforts the Italian tanks could not break through. Instead of attacking en masse, they went forward in groups of two and three, which were relatively easily dealt with by the hull-down cruisers of 2nd RTR. The British tanks had the advantage of radio, unlike most of the Italian tanks, which had to move to an objective and then stop while the commanders dismounted to receive orders. Later in the morning, as cold heavy rain began to fall over the battlefield, three desperate attacks were made against the Combeforce block by units of Italian Bersaglieri supported by light tanks, but were beaten off by the anti-tank guns. Despite the capture already of thousands of prisoners, many Italian units remained full of fight, although their efforts were now increasingly tinged with desperation. At the Pimple the light tanks of the 3rd and 7th Hussars harassed the extended flanks of the column and engaged much of the Italian artillery, breaking up the groups of tanks making their way towards the cruisers of 2nd RTR.

At noon on 6 February, with 2nd RTR and the 7th Hussars down to ten operational tanks between them, 1st RTR from the 7th Armoured Brigade arrived in the nick of time and smashed into the Italian flank at the Pimple, firing everything they had into the packed Italian columns. ‘There were endless targets,’ recalled Rea Leakey, ‘and on the first day of this battle my tank ran out of ammunition twice.’ As the afternoon wore on, despite continued heavy fighting it was clear that the Italians were losing heart. Vehicles and men were attempting to flee to the north-west, but the British trap held: the Hussars harassing the Italian column from the rear, 1st RTR flaying its flanks and 2nd RTR resisting any attempt at the road block to break through.

With total viable British tank strength reduced to thirty-nine ‘runners’ the Italians mounted a series of fierce night attacks against the 2nd Rifle Brigade’s positions at Sidi Saleh. Although the first attack penetrated the Rifle Brigade’s defences the onslaught was held, the combination of mines, anti-tank fire and the 25-pounders of the RHA proving too strong even for the gallant Italian Bersaglieri. The attacks continued, accompanied by heavy Italian shellfire, on the morning of 7 February, and once again the Rifle Brigade positions were penetrated, this time by M13 tanks, one of which was only halted outside battalion headquarters. The cruisers of 2nd RTR had withdrawn during the night south from Beda Fomm to support the heavily pressed Combeforce block, and helped push back the Italian tank attack that morning. In total more than 100 Italian tanks were knocked out and 50 of them were abandoned and captured by British and countless motarised vehicles wreckage belonging to 10th Italian Army dotted across landscape of Beda Fomm and Pimple.

To the relief of the exhausted British this was the final Italian effort. Gradually the noise died down and Joly became aware of a startling change on the landscape in front of his tanks’ positions at Sidi Saleh: First one and then another white flag appeared in the host of vehicles. More and more became visible, until the whole column was a forest of waving white banners.’ The Italian 10th Army was surrendering. ‘Italians of all shapes and sizes, all ranks, all regiments and all services swarmed out to be taken prisoner.’ They included some women. Joly’s gun loader shouted:

‘Look, sir, there’s a couple of bints there coming toward us. Can I go an’ grab 'em, sir? I could do with some home comforts.’ We took the two girls captive, installed them in a vehicle of their own and kept them for a few days to do our cooking and washing. I refrained from asking what other duties were required of the women, but noted that they remained contented and cheerful.

The battle for Libya was over. Strewn across the battlefield was the detritus of a defeated army – broken and abandoned equipment, tattered uniforms, piles of empty shell and cartridge cases. The ground was littered with paper, rifles and bedding. Here and there small groups of Italians tended their wounded. Others were collecting and burying the dead. Still others, less eager to surrender than the majority, stood or lay waiting to be captured. Some equipment was still burning furiously, more was smouldering. Many oil and petrol fires emitted clouds of black smoke. ‘We were well content,’ Joly remarked, as calm returned to the scene and he was able to enjoy the luxury of reflection. ‘Except for the Matildas, our equipment had not been greatly superior and we had at no time superiority in numbers. Speed of manoeuvre and preparation, determination and the confidence born of a great and growing moral ascendancy were the weapons which had brought the final victory.’ (in summary , operational method of warfare in British and Commonwealth forces were much more superior than Italians and they exctracted maximum efficiency from their forces deployed in front or rear and that maximum efficiency was much more than Italians best performance. Later when Germans Afrikakorps entered to picture in North Africa , it is revealed that their own operatinal method of warfare (mission oriented warfare) was more superior than British and their operational effectiveness , their battle group organisations and their certain weapns like anti tank guns were superior than Allies in war of movement. North Africa would be a harsh but necessary training ground for Allies)

At 11 a.m. General Virginio, chief of staff of the 10th Italian Army, arrived at the headquarters of Blood Caunter’s 4th Armoured Brigade to report that his commander, General Tellera, had been killed in a bayonet charge, and he was authorized to seek the surrender of the army. Generals Babini of the tanks, Bignani of the Bersaglieri, Negroni of the engineers, Cona, Bardini and Giuliano, along with many other senior officers of the Italian garrisons as well as the 10th Army, were taken prisoner, the greatest prize being Electric Whiskers himself, General Annibale Bergonzoli, who had managed to escape British clutches at both Bardia , Tobruk and Derna was captured by Lieutenant James ‘Nobby’ Clark of the 11th Hussars. Clark had caught Bergonzoli outside Benghazi. ‘When I stuck my tommy gun through the window of his Fiat, he said to me, “You got here a bit too quick today.”* He looked tired.’* Clark was awarded the Military Cross for his feat. ‘I haven’t seen so many Italians since the 1911 durbar,’ quipped General O’Connor who saw masses of Italian POWs.

Italian captives at Beda Fomm

The British plan to trap the 10th Army had worked, despite the British being outnumbered 4:1 in medium tanks and most of the Italian tanks being new, while the British tanks had covered more than 1,000 mi (1,600 km) since the beginning of Operation Compass in December 1940. The speed of the dash from Mechili had surprised the Italians, despite the obvious danger of such a move, especially when the British reached Msus on 4 February; had the Italians on the Via Balbia been prepared for a road block and made an organised attack, the 10th Army might have escaped. The British had gambled with the provision of fuel and supplies, which were capable only of sustaining a short operation and narrowly succeeded but the pursuit could not continue beyond El Agheila, due to broken-down and worn out vehicles. On 8 February, the 11th Hussars (advance guard of 7th Armored Division) patrolled westwards without air cover to the area 130 mi (210 km) east of Sirte , lifting prisoners and equipment and finding no organised Italian defences till reaching El Agheila on 9th February where they halted for good. An Italian tank battalion survived the ambush at Beda Fomm and bogged down in salt marshes around Agadebia surrendered to last man to a an British armored car patrol from 11th Hussars.

A few incidents lightened the atmosphere at this time. The Colonello commanding the bogged Italian light tank unit not only spoke fluent English, but enquired of his captors regarding pre-war friends serving with the 12th Lancers. On arrival at El Agheila in the pouring rain, the Hussars enthusiastically took advantage of the deserted Italian barracks to spend an unaccustomed night under a solid roof. Their plans were interrupted by the arrival of a Libyan senior NCO and his orderly on horseback, who informed Lieutenant-Colonel Combe that a further 400 fully-armed cavalry were lurking nearby and requested that the English please take them all prisoner. Rather than turf his men out from their dry billets into the rainy darkness, Combe sternly ordered the NCO to parade his men at 10:00 the following morning on pain of being shot if they failed to comply. All 400 duly turned up as instructed, accompanied by twenty Italian soldiers, some sailors, and an Arab woman. The Hussars were less amused on discovering an abandoned Italian remount depot. The horses therein, some of which were wounded or carried other injuries, had been left unfed and without water for a considerable period, and one troop spent the afternoon of 9 February leading the animals individually to a watering point and making up feed while their compatriots probed Tripolitinia. What relieved Hussars was capture of intact Italian barracks at El Agheila. They had a well deserved rest

In summary O’Connor’s 13th Corps did not have means or strength left any more , ( most of the vehicles needed repair or replenishment ) to push further east even if Whitehall and Imperial General Staff in London ordered him to march Tripoli immediately instead of preparing for Greek Expedition. O’Connor requested through Wavell that the government reconsider the conquest of Tripolitania, just as the Greek government announced that it would resist German aggression and accept reinforcement by the British if sufficient forces could be made available. Only a few thousand men of the 10th Army had escaped the disaster in Cyrenaica but the 5th Army had four divisions in Tripolitania and the Italians reinforced the Sirte, Tmed Hassan and Buerat strongholds from Italy, which brought the total of Italian soldiers in Tripolitania to about 150,000 men. The Italian forces in Libya experienced a “renaissance” during 1941, when the 132nd Armoured Division Ariete , the 102nd Motorised Division Trento , and the 101st Motorised Division Trieste arrived along with better equipment.

The success of the 7th Armoured Division encouraged a (a very mistaken) belief in the Royal Tank Regiment, that manoeuvre could win battles but the engagement with the Babini Group on 24 January, also led to the conclusion that armoured divisions needed more artillery. No integration of tanks and infantry was considered necessary or that anti-tank guns should be used offensively and the lack of cover from air observation in the desert encouraged dispersion to avoid air attack, where the British lacked air superiority, at the expense of the concentration of fire power at the decisive point. Due to the exiguous nature of supply and transport, conservation during lulls also encouraged the use of small Jock Columns , of a motorised infantry company, a field-gun battery and several armoured cars. The success of such columns against the Italians, led to exaggerated expectations which were confounded, when better equipped and trained German troops arrived in Libya. The 7th Armoured Division concluded that the defensive mentality of the Italians, had justified the taking of exceptional risks which would be unjustified against German troops who had best operational method of engagement in active operations (mission oriented approach) and went for maximum efficiency and exploitation in the field oppurtunities. (British would get a first hand training about that from Rommel and Afrikakorps from hard way for next 18 months)

Over 25,000 Italian prisoners, 100 Italian tanks, 216 guns and 1,500 other vehicles were captured along the road between Sidi Saleh and Beda Fomm by 13th Corps. 10th Italian Army was wiped out literally. The cost to the British was nine men killed and fifteen wounded. ‘I’m sorry you are so uncomfortable,’ General O’Connor apologized to his senior Italian officer prisoners after the battle in their temporary POW cage at Solluch. ‘We haven’t had much time to make proper arrangements.’ ‘Thank you very much,’ General Cona replied politely. ‘We do realize you came here in a very great hurry.’ Sending a message back to Cairo to alert Wavell to the scale of the 13th Corps achievement, O’Connor described the situation in the language both men knew and understood: ‘Fox killed in the open.’

Italian tanks captured at Beda Fomm

While the 7th Armoured Division was making its epic dash across the desert to Sidi Saleh and Beda Fomm, the Italians in the north of Cyrenaica were being pressed back along the coast by the Australians: cannibalizing vehicles, siphoning fuel to enable the runners to continue round the clock and recycling sixteen Italian M11 and M13 tanks. 6th Australian Division cavalry regiment was delighted to acquire armour at long last; Bren gun carriers did not have the cachet or usefulness of even abandoned Italian tanks. To prevent errors in identification, large white kangaroos were painted on each side of the hull and turret and on the frontal armour of the tanks. When the 2/8th Battalion reached the outskirts of Benghazi on the evening of 6 February the brigade intelligence officer, Lieutenant Knox, drove into the town leading a patrol of Bren gun carriers. The inhabitants were waiting for them and somewhat disconcertingly almost the entire population of Greeks, Jews, Italians and Arabs turned out to wave and cheer the conquering Australians. At the town hall the mayor, bishop, police chief and other officials greeted the weary and dust-covered Diggers with protestations that the Australians were ‘our brave allies’. The following morning, when the men of the 2/4th Battalion marched into the town square, they were met by thousands of inhabitants clapping and waving in an atmosphere of cordiality. Before long the troops were sitting in cafes drinking Chianti and strong black coffee, to the amazement of the natives, who had feared the conquerers would loot and pillage.

It took three days for news of the scale of the triumph to reach Cairo, the Countess of Ranfurly excitedly noting in her diary entry for 10 February 1941, ‘The Seventh British Armoured Division (Desert Rats) has made a brilliant spurt and cut off retreating Italians about sixty miles south of Benghazi and captured an immense quantity of prisoners and equipment.’ Back in London following his visit to the Middle East Anthony Eden joked in a note to the prime minister, ‘Never before has so much been surrendered by so many to so few.’ During an offensive of two months O’Connor’s tiny force had advanced 500 miles and destroyed the entire Italian 10th Army, captured 133,000 prisoners, 400 tanks and 1,290 guns, 1.250 aircraft from Italian airforce were either shot down but mostly captured damaged on abandoned Italian airfields , besides vast quantities of other war material. 22 Italian generals were captured. Total British Commonwealth casualties had been 500 killed, 1,373 wounded, and 55 missing.