from “Combined Operations , The Official History of Commandos” - Hillary St. George

“Striking Back” Britains Airborne and Commando Raids - Niall Cherry

enwikipedia.org

Norway had fallen into German hands in the early summer of 1940 together with the bulk of her industrial capacity. The Lofoten Islands were a sparsely populated group of islands just to the north of the Arctic Circle and situated about 900 miles from Scotland. Their main activity was fishing in the rich waters of the Northern Cape. Around 50% of Norway’s herring and cod oils were produced on the Lofoten Islands. As well as the actual fish themselves, there were associated industries using fish by-products, namely cod and herring liver oil for medicinal purposes. Another important asset for the Germans were several factories involved in the manufacture of glycerine, this was deemed to be an important raw material used in the manufacture of high explosives. The factories were located in four ports on different islands in the group – Brettesnes, Henningsvaer, Stamsund and Svolvaer.

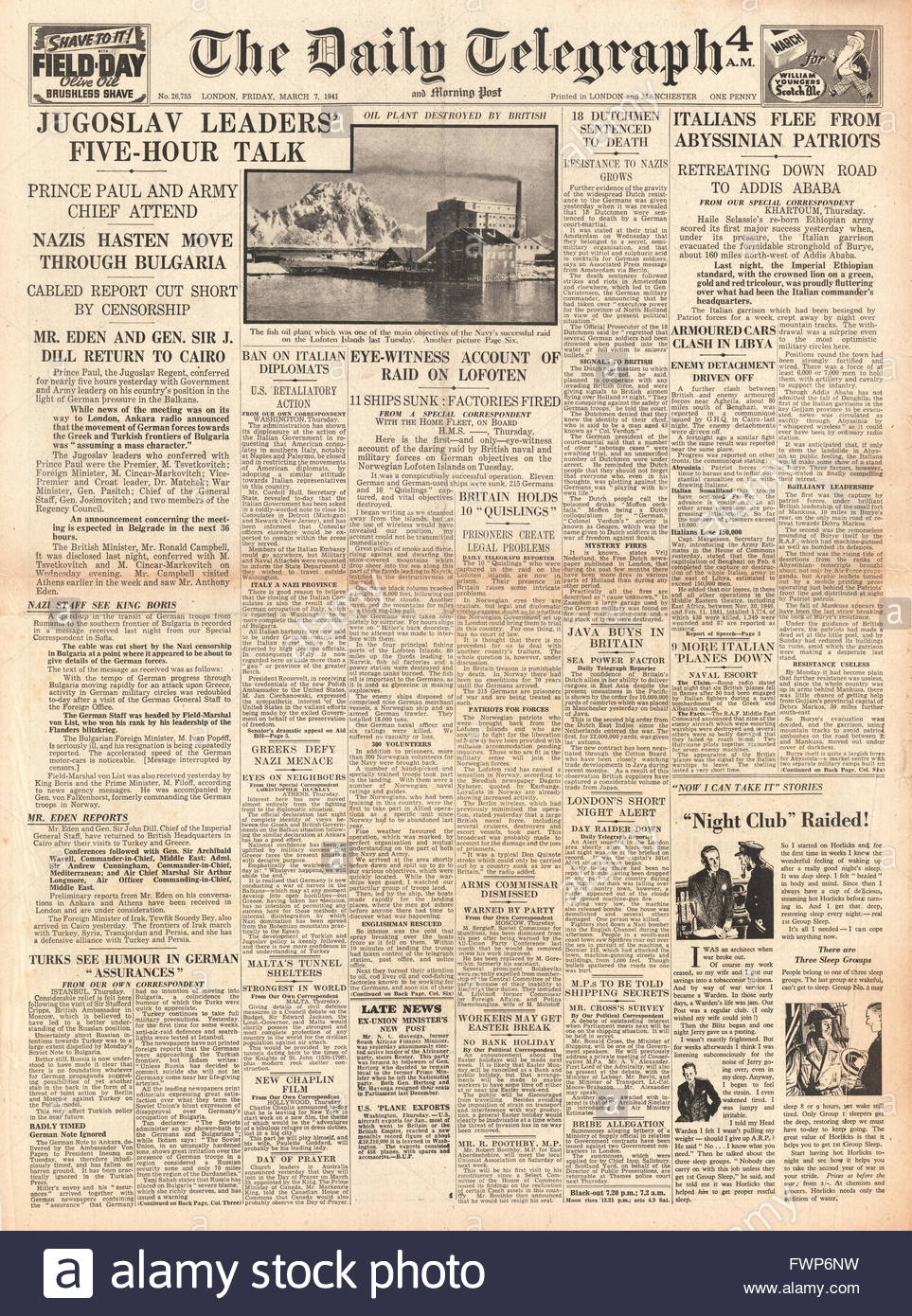

The Lofoten Islands had with the rest of Norway fallen into German hands in the early summer of 1940. The herring-and cod-oil factories situated in the four ports of Stamsund, Henningsvaer, Svolvaer and Brettesnes had been taken over by Germans and were supplying them with fish oil. All the oil produced was being shipped to Germany, which extracted the glycerine, a vital ingredient in the manufacture of high explosives , a product of which he stood-in great need and plus an important ingredient in vitamin medicine production for German troops on field duty. On February 1941 , it was decided by War Office and Combined Operations to send a combined force to destroy the factories , destroy all German shipping in the islands , capture the quislings and their German masters, and enlist recruits for the Norwegian Forces. The whole operation was given the codename of Operation Claymore.

Any ships found in the ports would be taken or sunk. The naval forces, under the command of Captain C. Caslon, R.N., consisted of five destroyers, the HMS Somali, HMS Bedouin, HMS Tartar, the HMS Eskimo and the HMS Legion. They were escort to two infantry landing ships (HMS Queen Emma and Princess Beatrix) commanded by Commander J. Brunton, RN., and Commander C. A. Kershaw, R.N., carrying No. 3 and No. 4 Commandos (battalions) and some Royal Engineers. , total 500 troops. The military force commander was Brigadier (now Major-General) J. C. Haydon, D.S.O., O.B.E., commanding the Special Service Brigade into which the Commandos had been formed. A detachment of Norwegian soldiers and naval ratings, under their own officers, took part in this raid (57 of them) , in the planning of which Norwegian officers collaborated. The raiding force assembled, and waited a week while its commanders perfected their plans. These were not easy to make, for though, as it chanced, there was to be no fighting ashore, this could not be known beforehand, and arrangements had to be made to deal with opposition during the landings, and with any enemy naval forces there might be in the neighbourhood. The tortuous nature of the approaches to the ports would make it impossible for the destroyers to come close inshore to give covering fire if it were needed. The leading landing craft were therefore ordered to act as scouts so that all would not be subjected to fire at one and the same moment.

HMS Somali

The troops were also given sufficient rations to enable them to remain ashore for 48 hours, if necessary, should the escorting destroyers be forced to leave the neighbourhood of the islands in order to fight a naval action. The naval task force known by the codename Rebel left Scapa Flow and headed towards the Faroes. They berthed in the Skálafjørður at 19:00 hours 1 March 1941 to take on fuel. Refuelling took five hours and the naval task force set out again heading northwards towards the Arctic to avoid detection by German air and sea patrols. They then turned east and headed towards Norway. They arrived at the Lofoten Islands during the early morning of 3 March 1941, just before 04:00 hours. Entering the Vestfjorden they were surprised to see all the harbour navigational lights illuminated, which they believed to be a sign that they were not expected and had achieved complete surprise. Any Germans in the area fell into the malaise of any soldier in a quiet, rear area thousands of miles from the front line, in that ‘it’ll never happen to me’. Indeed there were very few Germans in the area, the Lofotens probably not even registering on their radar as a potential target.

The raiders, with a Norwegian pilot on board each ship, entered Vest Fjord on the night of Monday, 3rd March, 1941, and at three o’clock in the morning “the many navigational lights in the neighbourhood of the Lofotens came into view.” That they were burning seemed to show that the arrival of the force had been unheralded. This was so; the surprise vas complete. The navigation of the Royal Navy had been as brilliant as the sunshine which gilded the landing craft when they moved away from their parent ships over the tumbling waters of the fjord towards the snow-covered islands ahead. Though the sun shone so brightly, it was very cold. “I was wearing two vests, two pullovers, a shirt, a Gieves’ waistcoat, a wool-lined mackintosh and a pair of fur-lined boots,” says one of those who took part, “and I was still cold.” Four landings were made, No. 3 Commando going ashore at Stamsund and Henningsvaer, and No. 4 at Svolvaer and Brettesnes. At no point was any opposition encountered, while the inhabitants welcomed landing Commandos very warmly. Gifts were exchanged, and it says much for the great spirit of the Norwegians that, far from resenting the demolitions which could not but destroy the livelihood of many of them, they were anxious and eager to help. 316 volunteers from local Norwegian population, including eight women and the English manager of the firm of Allen and Hanbury, joined the expedition and returned to England with it. It had been originally intended to take back men only: but one of the English officers reported by wireless that there were eight Norwegian ladies anxious to join the Norwegian Red Cross. Could we take them off? Permission was granted.

One of the officers (Lieutenant R Wills) from No 3 Commando went to the post office at Stamsund and asked for a telegram to be sent to a Mr A Hitler, Berlin. It read, “You said in your last speech German troops would meet the English wherever they landed STOP where are your troops? Wills 2-Lieut”. Regretfully it is not recorded whether the telegram was ever delivered.

The Germans prisoners captured by Commandos numbered 226 (most of them were either crews of merchantmen or members of a small Luftwaffe signals station detachment based there and two SS members) , plus ten Norwegian quisling colaborators rounded up by the Norwegian detachment. A Luftwaffe wireless station was captured and put out of action by Commandos. An electricity-generating plant was also destroyed. The demolitions on shore were carried out by the party of Royal Engineers. They destroyed eleven cod-and herring-oil or fish-meal factories, an electric-light plant and all the oil tanks with their contents, 800,000 gallons of oil. Five Germans ships , total of a maximum tonnage of 21,900 were destroyed at the port, four of them by a naval demolition party, and the fifth, the SS. “Hamburg”— a large factory and refrigerator ship of 9,780 tons— by the gunfire of destroyer HMS Tartar. At sea the only opposition came from a German armed trawler, “Krebs,” sighted soon after 6 a.m. sailing out of Stamsund. Despite the odds, she showed fight and courageously engaged the headquarters ship, destroyer HMS Somali, which soon opened up and set Krebs on fire. Krebs , badly damaged , ran aground on a small island, drifted off three hours later, and surrendered. Fourteen of Krebs crew died. Her survivors , twelve of them , were taken prisoner by HMS Somali and Krebs was sunk by gunfire. Her captain had been killed at the beginning of the engagement. The prisoners were astonished at the treatment they received, for they had expected something very different. It had, they said, been front-page news in Germany that the captain of the HMS Cossack had shot the whole crew of the “Altmark.”

Very soon after the start of the operation the local Norwegian fishing fleet put to sea, and presently, in the words of the Naval Commander’s report, “there were literally hundreds of little fishing smacks and small puffers beginning to fish in the adjacent waters. It quickly became clear to them that our operations were directed against the Germans and that they were not to be molested. They showed their friendliness and enthusiasm by cheering and waving and hoisting Norwegian flags.” They also loaded the decks of the HMS Somali with freshly-caught fish while she lay stopped during the boarding and searching of the trawler Krebs. By 1 p.m. the troops had re-embarked and the expedition sailed for home, leaving behind it the wreckage of the herring- and cod-oil industry in that part of Norway and a number of valuable merchant ships at the bottom of the fjord. It reached Scapa unmolested, exactly two days later. The casualty figure for the Commandos is thought to have been only one – an officer who managed to achieve a negligent discharge from a pistol he had put in his pocket and shot his own leg.

The aim of the operation had not been to sink ships, however, but to capture a German Enigma machine used by the Navy, whose code keys had been proving virtually impossible to break. One such Enigma machine was on board the Krebs ; its commander, Lieutenant Hans Küpfinger, had managed to throw his machine overboard before he was killed. He had insufficient time, however, to destroy other elements of the Enigma message procedure, including his coding documents and spare coding rotors and these were captured by British boarding party that searched Krebs and brought back to UK. So that after three weeks’ intensive work at Bletchley Park Goverment Cypher School, it became possible for British Intelligence to read all German naval traffic in home waters for the last week of April and much of May, with only a relatively short delay of between three and seven days.

The Norwegians were to suffer for the Lofoten Islands raid, Josef Terboven Reichs Kommissar of Norway setting up at once, as Nazi Propaganda Minister Goebbels wrote in his diary five days later, ‘a punitive court of the harshest kind’. The farms of ‘saboteurs’ were to be burned, and hostages taken. ‘This fellow Terboven is all right,’ Goebbels added. ‘One does not need to pussyfoot with him; he knows himself what he must do.’ (Germans never found out Enigma code materials were captured from armed trawler Krebs though)

After the raid, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill issued a memo “to all concerned … my congratulations on the very satisfactory operation”. Claymore was the first of twelve commando raids directed against Norway during the Second World War.