The $1.2 trillion spigot; capital spending in U.S. just keeps on keeping on

By Louis Uchitelle

Exodus Communications Inc., born of the Internet, lost money this year. And last year. And the year before. But it is spending hundreds of millions of dollars anyway on new high-technology centers to house and operate the Web sites of hundreds of clients.

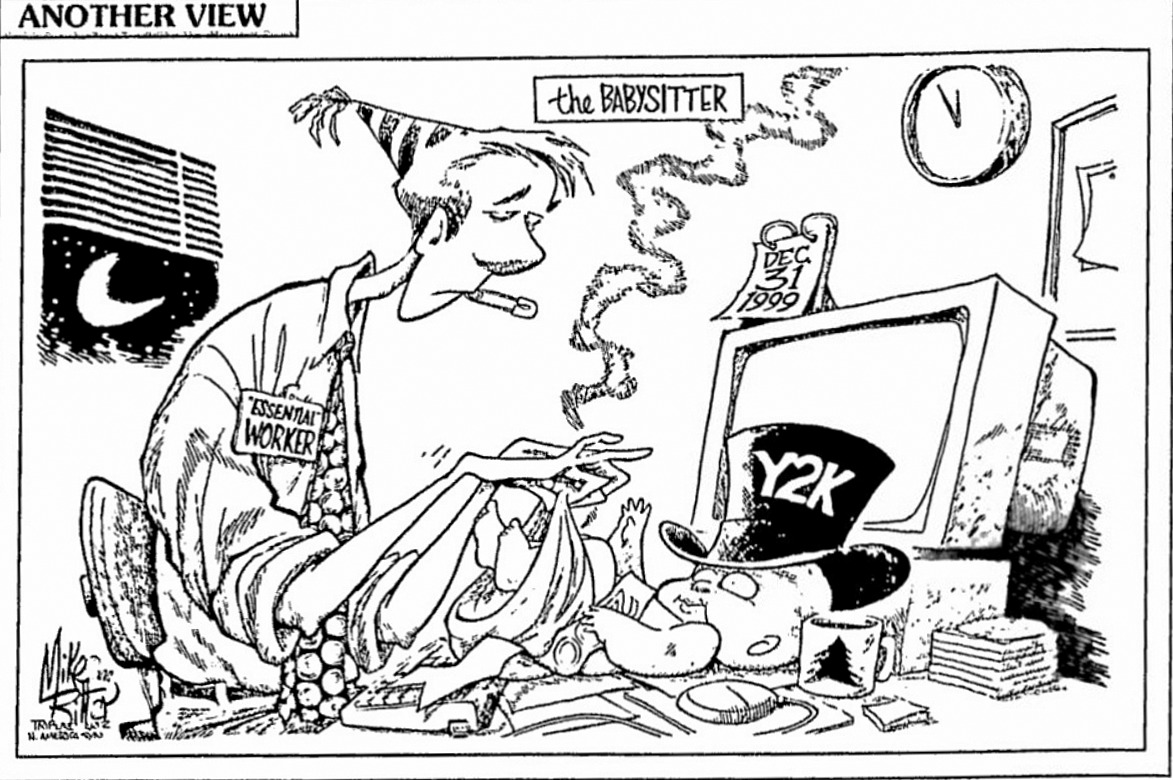

Forget about the Year 2000 date switch. Companies like Exodus – young, profitless, but gambling on a golden future – help to explain why capital spending has not faltered despite all the fears among experts that business investment would slow in the fourth quarter as corporate America braced for the millennium.

The investment slowdown has not happened and is not likely to happen early next year either, even after all the spending to fix the Year 2000 computer problem slows to a crawl. Quite the contrary: The capital spending boom that has lasted for much of the decade appears to have plenty of steam to continue well into the new year, sustaining in the process the nation’s robust economic growth of roughly 4 percent a year since 1995.

“If you are a corporate executive, and the economy is strong and labor is scarce and financing is inexpensive, as it is today, what do you do?” asked David Wyss, chief economist at Standard & Poor’s DRI forecasting unit. “You buy new equipment, or more equipment, and increase output that way and cut production costs in the bargain.”

Strong consumer demand, new technology and relatively low interest rates, which reduce the cost of new investment, have all contributed to the investment boom. So has the frequent replacement of office computers with faster and more powerful ones. High on the list of contributing factors is the constant retooling to make new products. Consumers are increasingly willing to pay more for new models or new twists on existing models, and these changes are made more frequently now than in the past.

That is the case at the DaimlerChrysler Group, where model changes now come every five years instead of every six to eight years, and $8 billion in capital spending in 1999 is expected to rise to $9 billion in 2000 in the United States. “Almost all of this is direct spending to develop and make new models,” said Wynn Van Bussman, chief corporate economist at DaimlerChrysler. “Computer spending for Y2K is lost in the rounding off of these billions.”

Capital spending represents the total cost of all the new factories and office buildings, machinery, software, computers and other equipment that companies acquire to produce their goods and services in this country or to expand and modernize their operations here. Such spending in the third quarter, the Commerce Department reported last week, came to $1.2 trillion at an annual rate, or 12.7 percent of the value of the national economy.

That is the highest percentage since the early 1980s, a decade in which businesses around the country revamped operations to meet the challenge of formidable Japanese and European competitors.

In contrast to the 1980s, very little of the $1.2 trillion is being spent on new factories, office buildings and other structures. Most of the investment, $910 billion, has gone for machinery and equipment, particularly computers and software. In the late 1990s, spending in these high-technology sectors has risen faster than any other aspect of capital spending, reaching an annual rate of $247 billion in the third quarter. The rise reflects substantial real gains, but it also flows, in part, from a peculiar way of pricing computers in the official statistics.

If a computer cost $2,000 in 1998 and a more powerful version in 1999 still sells for $2,000, the Commerce Department assigns a value to the extra power, say $500. The computer then enters the government’s investment account at $2,500. That sort of bookkeeping, a rough guess that may overestimate the genuine advances in computing, has fattened capital spending in an age of frequent breakthroughs in technology.

The investment boom is easier to see and touch in other industries. Aircraft orders, for example, have more than doubled since 1996 as airline passenger traffic has risen. Electric power shortages that first appeared in the Midwest and Southeast three summers ago have set off a rapid expansion of generating plants fueled by natural gas. The demand for more gas, in turn, has raised investment in that industry.

“The price spikes that accompanied the electricity outages were a signal to step up investment,” said Lawrence Makovich, director of electric power research at Cambridge Energy Research Associates. Power companies have increased their investment to $8 billion a year in the United States from $2 billion in 1997. Further, during the last 18 months the industry has announced projects, Mr. Makovich said, that should eventually increase the generation of electricity in this country by more than a quarter.

New technology is a big source of capital spending. The Internet is an eye-catching industry in mid-construction, giving rise to hundreds of start-ups like Exodus, which operates computer networks for companies with Web sites. On Wall Street, investment firms like Merrill Lynch are spending hundreds of millions of dollars for Internet links and online trading. And big telephone and cable companies are rewiring American homes, hoping to provide each with a single new connection that will carry not only voice communication but also cable television, e-mail and high-speed Internet traffic.

“What is driving us is the exploding technology, not the strong economy,” Eileen Connolly, a spokeswoman for AT&T, said, though she acknowledged that the two can be hard to separate.

Optimistic investors are also a prod to capital spending. Their enthusiasm finances the expansion plans of companies like Exodus, whose stock price has soared 985 percent this year.

“People are convinced,” said Kenneth J. Matheny, a senior economist at Macroeconomic Advisors Inc., “that Internet-based methods of distributing information and products will turn out to be much more profitable than traditional methods.”

Exodus, which is based in Santa Clara, Calif., with 700 employees, operates at 15 locations around the United States and one in London. The buildings resemble large warehouses from the outside. Inside are the computers, servers and communications gear that store and manipulate Web sites and make them appear on computer screens around the world at the click of a mouse.

Each location cost Exodus about $50 million, and from the start of this year to the end of 2000, the company expects to spend more than $750 million – most of it next year – on 15 more locations, the majority to be erected in this country.

That is quite a feat for a company with only about $200 million in revenue this year from 1,700 customers. Making the feat possible are the rising stock market and the optimism of investors who gamble that Exodus will emerge from intense competition as a dominant player and thus a cash cow in a key industry in the new information economy.

“We are well positioned in a market where the demand is outstripping the supply,” said Adam Wegner, vice president and general counsel. He says that without the heavy spending on expansion, Exodus would be profitable today. But he also points to a Catch-22: Without the expansion, competitors would push Exodus out of the business of managing Web sites. “The whole name of the game is to expand to supply the growing demand,” Mr. Wegner said.

That takes money. Exodus went public in March last year, raising $70 million with an initial public offering at $15 a share. Since then, the stock has split two-for-one three times, and its shares closed yesterday at $86.625 in Nasdaq trading. With that strong performance as backdrop, Exodus has raised $1.52 billion on the bond market, through four high-yield offerings. These are the securities that in the 1980s were called junk bonds, a term now out of fashion even though the high risk is the same.

The last and biggest offering, $1 billion, took place this month, and Exodus now faces $100 million a year in interest payments. That represents a huge chunk of its annual revenue but is a burden made lighter through its soaring stock price.

The expectation that share prices will keep rising has become “a big component of capital investment,” said Robert Pollin, an economist at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

A rising stock market also encourages capital spending among companies that do not need to raise money from the markets. That is because a rising market makes an investment in new equipment automatically worth more as a company’s share price rises, effectively raising the resale value of the new equipment.

But if capital investment is rising in many industries, it is notably absent in others. Some oil companies are just beginning to respond to higher petroleum prices, announcing that if prices hold up they will increase spending on exploration and drilling. Excess production capacity inhibits the steel industry and paper and pulp companies, which have shut down older mills. Phelps Dodge, the big copper producer, is holding back, too, even though the demand for copper is strong.

“All the interest that people have in quality of life drives copper demand,” said Thomas Foster, vice president and controller at Phelps Dodge. “Telephones in every room, pop the trunk with a button rather than a key – all these things use copper. But the market can’t handle more investment now.”

Even a high-technology company like Motorola is cautious, preferring to outsource its production to manufacturers in Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. “We don’t have to pump the capital into expansion,” said Scott Stevens, a spokesman for Motorola’s semiconductor business, “but we are locking in the available capacity that we need and faster than if we went and built it with our own bricks and mortar.”

That is certainly not the mood, however, among the thousands of companies, many of them newly incorporated, that are opening Web sites. iVillage is in this herd, creating an Internet site that offers all sorts of information and shopping leads, of interest mainly to women.

“We are spending between $5 and $8 million a year on capital investment, primarily for computers, servers and communications gear,” said Craig Monaghan, chief financial officer at iVillage, which is four years old and has 400 employees.

Even a stock market correction might not inhibit iVillage, although the profitless company pays for capital spending by raising money through share offerings, the most recent last summer.

If its stock price fell sharply, would iVillage cut back on investment? Not right away, Mr. Monaghan said. “We have sufficient cash on hand so that we can fund our operations for a while.”