22-23 of December, 1940: The feats of submarine Papanikolis

Papanikolis was, indisputably, the most celebrated submarine in the history of the Greek Navy.

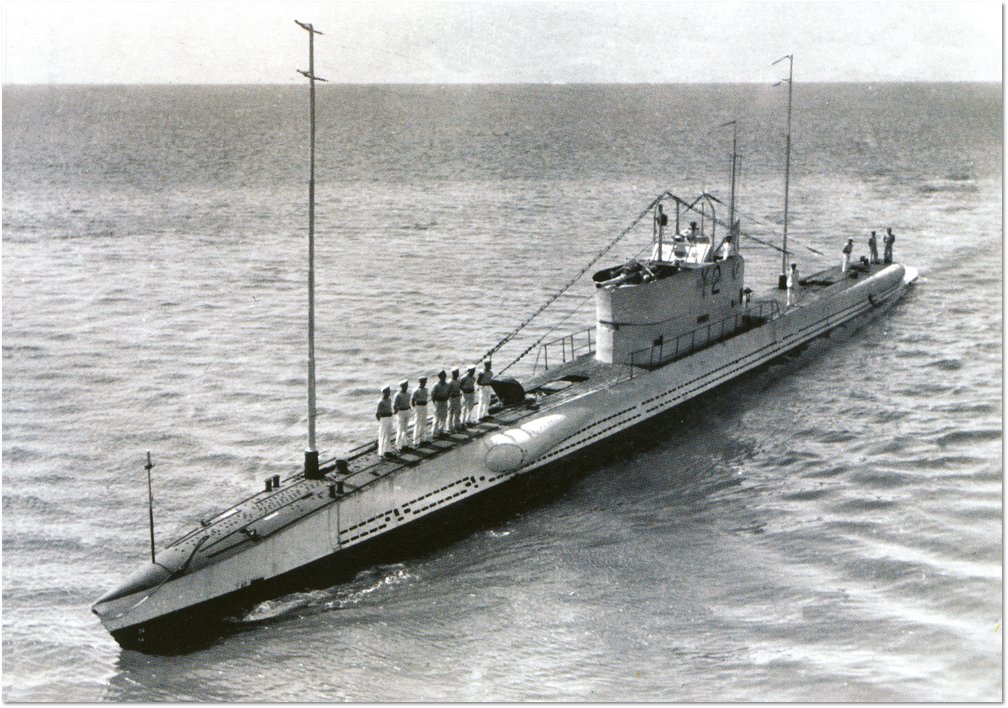

Papanikolis , together with her sister ship, Katsonis , formed the first class of Greek submarines ordered after the First World War. She was built at the Chantiers de la Loire shipyards between 1925–27, and commissioned into the Hellenic Navy on 21 December 1927. Its first captain was Cdr P. Vandoros. It was named after the Greek War of Independence hero, Dimitrios Papanikolis.

Greece was trying to update her navy according to her financial capabilities, but in any case, the Navy received the least money, as in the event of the war, it was calculated that the British Navy would support Greece. The country entered World War II with a navy consisting of 2 battleships, 1 armoured cruiser, 14 destroyers, and 6 submarines, a force obviously not comparable with the Italian Royal Navy.

Since a direct combat against the Italians was out of question, the mission of the Navy was to patrol the area near Dodecanese and the Ionian islands, but always inside Greek territorial waters, and to transport soldiers from the islands to the mainland.

The Greek government, wishing a naval success along with the victories in the Albanian front, for propaganda, ordered Papanikolis for its second mission (December 17 - December 27, 1940) to come out from the Greek territorial waters and patrol the Straits of Otrando to harass the Italian naval lines of reinforcements to Albania. Papanikolis’ captain was Lieutenant Commander Miltiades Iatridis, known as a daring and insubordinate officer, and his Executive Officer was Lieutenant Vasileios Arslanoglou, an Anatolian Greek born in Mersin, who was the strict keeper of rules in the submarine (he was killed in Malta, on February 27, 1942, during a Luftwaffe bombardment).

Οn 22 December 1940, Papanikolis sank the small Italian motor ship Antonietta, and, on the very next day, the 3,952-ton troop carrier Firenze near Sazan Island.

Despite the obvious inability of the Greek Navy to disrupt the Italian sea routes, the victories of Papanikolis were widely celebrated and became another morale boost for the rest of the War. Iatrides was immediately promoted to Commander and Arslanoglou to Lieutenant Commander.

After the Battle of Greece, Papanikolis managed to survive and took refuge to Alexandria along with the surviving Greek Navy, and continued the fight until 1945, when it was decomissioned. The submarine was sold for scrap, except its conning tower which was preserved and is on display in the Hellenic Maritime Museum at Piraeus. Two more submarines of the Greek Navy were named as “Papanikolis”, honoring the legacy of the legendary ship, an ex-US GUPPY-IIA boat, in service between 1972–1993, and a Type 214 submarine class, in service since 2010.

Commander Miltiades Iatrides, commander of Papanikolis

Vasileios Arslanoglou (1908-1942), named Commander after his death

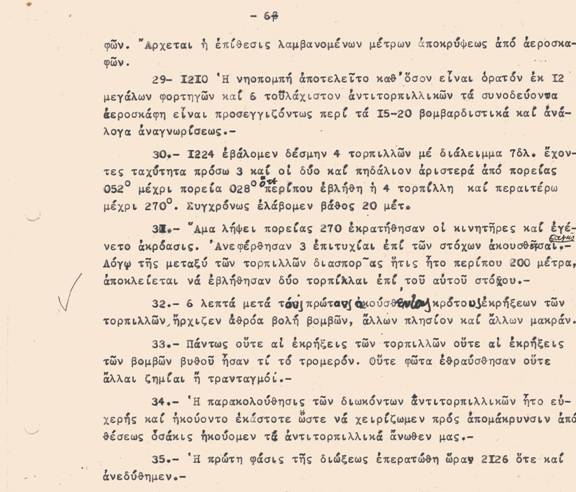

An excerpt of Iatridis’ official report about Papanikolis feats

Papanikolis conning tower as it is today in the Hellenic Maritime Museum.