The Evening Star (December 25, 1942)

Assassination of Adm. Darlan of Axis origin, associate charges

Giraud reported taking steps to maintain order

By Noland Norgaard, Associated Press war correspondent

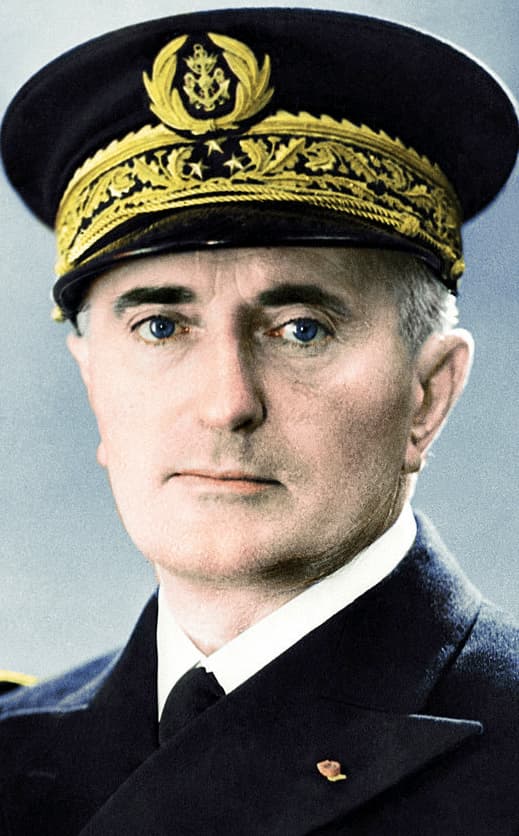

Adm. Darlan

Algiers, Algeria –

Adm. Jean Darlan, who surrendered North Africa and yielded Dakar bloodlessly to the Allies, was shot to death on the eve of Christmas, and one of his closest associates said today the assassination was inspired by the Axis or its collaborationists.

The Algiers radio announced that Gen. Henri Honoré Giraud, implacable foe of the Germans and Adm. Darlan’s commander of French forces in the North African field alongside the Allies, had taken over “maintenance of order” in French North Africa.

Thus, for the moment at least, the old-school French general who said he preferred fighting to politics stood virtually in the little admiral’s place, at the head of the French in North Africa.

The Morocco radio said the Imperial Council would name Adm. Darlan’s successor tomorrow. The council, set up by the admiral to govern North Africa and “defend the interests of the French Empire” until France is liberated, included Adm. Darlan and these five men, one of whom probably will be chosen: Gen. Giraud, Gen. Jean-Marie Bergeret (former Vichy Air Minister) and the three governors-general in French North and West Africa (Gen. Auguste Noguès of Morocco, Pierre Boisson of West Africa, and Yves Chatel of Algeria).

The Morocco broadcast said Gen. Noguès had left Rabat by plane for Algiers early today to attend the council meeting. It announced that a special mass would be celebrated in Adm. Darlan’s memory tomorrow in the Rabat Cathedral.

Assassin caught quickly

The assassin was caught in the government palace seconds after he fired the close-range shots which took the life of the one-time commander of all Vichy’s Armed Forces, high-placed member in Marshal Pétain’s collaboration cabinet, who said Marshal Pétain sent him to North Africa as his deputy.

Bergeret makes charge

Gen. Bergeret, close associate of Adm. Darlan, said the admiral was:

…the victim of an assassin inspired by those who did not pardon him for having taken up arms on the side of the Allies against Germany.

The assassin was said to be 22 years old. There was no official announcement immediately identifying him or giving a specific motive for his act. He used a .25-caliber revolver.

The Federal Communications Commission reported hearing a Paris radio broadcast declaring that Adm. Darlan was killed by a young Frenchman.

Gen. Bergeret called on all Frenchmen to unite:

…for the only fight that counts – the liberation of France.

The general, who was present in Compiègne Forest when the German armistice terms were handed to French representatives in June 1940 and stood by Marshal Pétain and Adm. Darlan throughout the trials of the Vichy government, said that:

All attempts at dividing the population will be crushed.

New realignment in making

Thus, less than 12 hours after the puzzling career of Adm. Darlan was ended, new realignments were in the making. The extent of these changes could not be estimated today.

Adm. Darlan, who brought French forces to the Allied side under an arrangement with U.S. Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower after resisting briefly, but furiously, the Allied occupation of French Morocco and Algeria, was wounded mortally about 3 p.m. yesterday as he was about to enter his office in the government palace.

Five shots rang out in the corridor leading to Adm. Darlan’s office and the little admiral, who had followed Marshal Pétain with almost fanatical zeal for more than two years, slumped to the floor at the doorway.

Adm. Darlan died just before his ambulance reached the hospital. The last sacrament was administered by a military priest.

Adm. Darlan’s body remained through the night in the hospital chapel with a guard of marine officers.

Called for ‘union – at once’

Shortly before he was killed, the admiral had given an interview in which he called for the "union – at once” of all Frenchmen fighting the Axis, but he admitted there are difficulties, even certain opposition.

Adm. Darlan had said the Imperial Council would eliminate relentlessly everything that might risk weakening our war effort.

The assassin had visited the government palace yesterday morning, but left when he was unable to see Adm. Darlan. He was in the waiting room adjoining the admiral’s office when Adm. Darlan returned to his office in the afternoon and fired five shots from a .25-caliber revolver and then started to flee. Adm. Darlan’s aide, Cdt. Hourcade, attempted to stop him and was shot in the leg.

The assassin was captured by one of Adm. Darlan’s aides, Adjt. Andrew Vuichard, when he attempted to leap over the admiral’s body.

Adm. Darlan was struck by two bullets, one wounding him in the mouth and other penetrating a lung.

Entertained tribesmen

Adm. Darlan’s amicable relations with Gen. Giraud, whose loyalty to the Allies has not been questioned and who is approved by the Fighting French, were indicated by the fact that only Wednesday he and Gen. Giraud entertained the Muslim tribal chieftains of Algeria at the governor’s palace. Gen. Giraud returned earlier in the week from an inspection trip in French Morocco.

Gen. Bergeret, in his statement appealing to the French for unity, said:

The designs of our enemies will not have any effect. This crime will not lessen our determination to liberate our country.

Cdt. Hourcade, a marine staff officer, was the only aide with Adm. Darlan when he walked into the palace and met the burst of gunfire. Cdt. Hourcade leaped at the assassin’s throat and the gunman fired at him. Adjt. Vuichard, hearing the shots, ran into the building and struck the young killer’s jaw with his fist.

The assassin told Adjt. Vuichard:

I surrender; my gun is empty.

Tried to kill assassin

Sword-bearing Spahis, who guard the palace, rushed in and tried to kill the assassin, but were stopped by officials. The killer was then turned over to the police. The palace gates, flanked by the marble busts of famous French military leaders, were shut to keep crowds from the scene.

Heavy guards were placed around public and military buildings following the shooting.

Adm. Darlan’s wife arrived at the hospital shortly after his death, but remained only a short time. His son was believed to be in Rabat, French Morocco, where he was flown recently for treatment of infantile paralysis.

The bullet which caused Adm. Darlan’s death struck the tip of his lung and lodged at the point of the heart. Physicians said death resulted from the severing of a large blood vessel.