Sudden storms and sudden death shook history’s greatest armada

By Charles Christian Wertenbaker

From air, the landings looked like scale model with LCTs (left and top), smaller LCTs (upper right), ducks (center). Tanks, vehicles are mounting road at right. Bottom object seems to be armored truck with raised apparatus for bridging barbed wire. A pillbox is on fire at bottom.

By cable from U.S. Force HQ ship in the English Channel –

D-Day minus three was a clear, mild day with a fresh breeze blowing in the Channel from the west. Aboard this ship, the USS Acamar (a false name), there were quiet, intense preparations for directing the battle ahead. AA and machine-gun crews were briefed; there was a general-quarters drill during the afternoon. Ship’s officers collected signatures on brand-new 100-franc notes which, with luck, would be their mementos of the invasion.

Every half hour or so, tank landing ships and infantry landing craft would appear around the headland to the east and glide toward us. The boats joined a swarm of similar craft. Each boat fitted closely against the next, as if for security, so that in the mass they lost all identity and became a floating island of men and metal. Only the movement of a hand or face showed that it was not all metal.

Late in the afternoon, the mass began to break apart; each boat became a boat again, and each man a creature with arms, body and head, and a brain to keep all together. The boats, hundreds of them in single file, moved to anchor. It would not be long. In all the ports, boats were moving, gathering, and along the coast, caressing the shore, one convoy of a thousand big and little ships was already on its way to a beach in Normandy.

At midnight, Gen. Eisenhower and his staff were studying the weather reports. For some days, they had known that a low-pressure area was moving eastward in the Atlantic but the weather experts had expected it to turn north before it reached the Channel. Instead, the gale had come straight on, with another slighter blow behind it. This was probably the hardest decision Gen. Eisenhower ever had to make. Perhaps he remembered the Spanish Armada and the disaster that overtook it. At any rate, sometime before dawn he chose the cautious course. At 5:45, the Acamar’s radio buzzed: “Stand by for important message.” Just before 6:00, the message came: The invasion is postponed for a minimum of 24 hours.

The landing boats scurried back. A brace of destroyers went barking after the thousand-ship convoy that was bearing toward Normandy with its radio sealed. All around the coast of England, ships, big and little, on missions, big and little, had to slow up or turn around, the greatest armada in history broke up before it was assembled.

D-Day minus two

Sunday, June 4, was a day of decisions perhaps more difficult to make than the one that had delayed the start by 24 hours. Because of the tides, there were only three days in early June when the invasion could begin. They were the 5th, 6th and 7th. The 5th had been picked for D-Day because on this day at 6:00, the tide would have been a little more than halfway between ebb and flood – that is, high enough to land fairly well up the beaches and on sand instead of mud, and low enough to land before the first series of beach obstacles were reached. Not for two more weeks, until June 19, 20 and 21, would a similar series of conditions again prevail. And so, on this Sunday, the decision to be made was whether to invade on Tuesday or Wednesday or whether to postpone the invasion for a fortnight.

All day Sunday, it blew a gale, churning up the water even where the Acamar and the command ship of Adm. Alan G. Kirk and Lt. Gen. Omar Nelson Bradley were sheltered. At 1:30 that afternoon, Gen. Bradley visited his headquarters ship to check reports and plans. The naval officers at the meeting wanted 48 hours to reassemble their forces. Gen. Bradley was in a hurry. Finally, Adm. Kirk agreed that he could be ready for Tuesday. The British were also ready. H-Hour was moved back by half an hour in the new tentative plan. Gen. Eisenhower promised a tentative decision by evening, a final, decision by 6:00 in the morning.

By evening, the new plans were worked out. By evening it was pouring rain. The wind whipped spray over the open boats and the rain blotted out the faces of the men in them. Some of them were ending their fifth day in the boats. “They’re pretty tough by now,” said an officer watching them through glasses, “but I’ll bet they’ll be glad to hit the beach.” “The poor sons of bitches,” said another, “they’re lucky to be where they are.”

Around 9:00, the gale had blown itself out and the smaller one following it was not so much feared. The forecast: clear Tuesday morning, with weather closing in by evening. That would be good for the airborne landings, for the air bombardment, for observation for the naval bombardment.

D-Day minus one

Monday morning at 6:00, the final confirmation came. The day was cloudy and cold. The staff officers looked at the sky, shrugged and put their trust in the weatherman. A sleepy colonel said, “Win, lose or draw – and there ain’t no draw – they can’t call it off now, thank God.”

By late afternoon, the command ship was gone. The small boats were gone. One by one the destroyers left the harbor. At 10:00, when the clouds broke and the low sun shone across the water, the harbor was almost empty. Then, gathering her flock of small boats around her ad with two destroyers shepherding the flock, the Acamar, last big ship to leave, set out under full steam for the invasion of France.

Two ducks and two halftracks towing 37mm anti-tank guns are already on beach, as men carrying Springfield rifles prepare to debark from LCVP.

Some seriously hurt wait to be evacuated. Foreground, an emergency first-aid kit and a Mae West.

Dead Americans end their adventure on a cobble-stoned beach of Normandy, probably toward the end of the peninsula. The worst casualties were taken in first half hour on beaches. German casualties included a surprising number of prisoners, few of them of first-line quality.

In the tall grass behind the beach, Americans seek cover while in the background tanks advance on a shelled house that was probably a Nazi strongpoint.

Truck moves over road completed by U.S. engineers and covered with mat while ahead the engineers detonate mines.

D-Day

Tuesday, June 6, the invasion began almost exactly on schedule at 30 minutes past midnight. That was the time when airborne troops began landing by parachute at six hours before H-Hour, the actual moment of land attack. At the instant, the first parachutist lowered his head and fell toward the earth of Normandy, U.S., British and Canadian Armies had afloat or in the air some thousands of men and thousands of vehicles.

Landing on the western beach in the target area went well; by 7:30 a.m., one hour and a half after the sixth hour of the sixth day of the sixth month of the year 1944, two regiments of infantry and some tanks were ashore. On the eastern beach, waves were higher, obstacles more stubborn and the enemy prepared; a fresh division had been rushed there a few hours earlier. On this beach all tanks were swamped. The entire beach was under enemy fire and on most parts of it boats could not unload. Not until early afternoon did the first waves get off the beach and begin to spread out in the high ground beyond the bluffs.

From the sea, most of the larger warships were moving toward the beach that needed support. Dense smoke rose where the B-17s had taken care of the enemy battery, firing straight down the length of the western beach. But off the eastern beach there was a steady thunder of heavy naval guns firing, and on shore smoke rising from the beach and the bluffs behind. Beyond a dim church steeple stretched the gray beach spotted with boats and vehicles, and beyond that green fields and towns.

At two places where landing parties had found exits from the beaches, destroyers standing in close to the shore were pouring fire into the valleys beyond the exits and enemy guns were firing in the valleys themselves. On either side of the valley heavier ships crashed broadsides deep into the interior. Their guns spat orange flame. The air seemed to tremble as they fired.

On into the night destroyers stood inshore firing intermittently. From the enemy also came sporadic shelling while the engineers on the beach worked to clear some of the wreckage. On the beach, fires flared and died down. Out beyond the line of destroyers hundreds of ships lying at anchor were dark and silent under a cloudy sky. At 11:30 that night, enemy raiders came and the night was lit with bomb bursts and with tracers firing into the clouds. One ship, hit, flared brilliantly for no more than five minutes, lighting the whole eastern sky, then suddenly went out. Shortly after midnight, three raiders fell slowly flaming into the sea.

D-Day plus one

After less than five hours of sheer night, lighter streaks low in the sky showed where the moon was. The horizon appeared again and by ones and twos and dozens and scores the great flotilla appeared. Warships made black silhouettes like those printed in Jane’s Fighting Ships, and the smaller craft were at first mere blobs of black. Then all became clearly visible, down to the guns of the warships and the men aboard the landing craft nearby waiting for the moment of landing. The first Flying Fortresses appeared and, as the light grew, the obstacles on the beaches stood out sharply in the queer pre-dawn pink that make dark things darker. From the shore still came the sounds of shelling and of rifle and machine-gun fire as the first 24 hours of the invasion ended.

In the full light of day, you could look down from a bluff through the opening of the river valley at the beach spread out below. It looked like a great junkyard. Fro, the water’s edge at low tide to the high-water mark were landing craft, some impaled on obstacles, blown by mines, shattered by shellfire and stranded by the ebbing of the tide. Among them, following a narrow path from the water to the valley’s edge, moved a line of sound vehicles and a company of men just landed. As they passed, some of the men turned to look at the wreckage through which they moved: there was a bulldozer with its guts spattered over the sand, and another with its occupants spattered, an arm here, a leg there, a piece of pulp over yonder. There were discarded things all over the beach: lifebelts, cartridge clips, canteens, pistol belts, bayonets, K-rations. Behind the beach, across a wide, deep tank ditch half full of water was the casemated German 88 that had caused much of the wreckage. A clean shell hole through the steel shield of its narrow opening showed how it had been put out of action.

Echoes of World War I speak in pictures of Americans in France passing dead Germans…

…and stopping in a town (below) beside a Romanesque church. But these are paratroopers, a spectacular innovation of World War II. At right below is a Shell gasoline station.

By the afternoon of D-Day plus one, the battle of this beachhead was already the most desperate of the invasion. The Germans had set up machine-gun positions atop the bluffs; and these, with ingeniously concealed batteries, had raked landing parties. Casualties of some of the assault forces had been high. Now most of the beach was still under shellfire. The intermittent hammer of machine guns made another sector untenable and only in two places could forces be brought ashore. They were needed quickly – especially artillery and artillery observation planes – for it was inland from here that Rommel was expected to make his first counterattack.

From the bluff you could see beyond the beach almost 12 miles to sea, and all this expanse of water was filled with boats. There were, by a quick rough count, 665 vessels lying offshore, from the large transports on the horizon to the small landing craft near the beach. About five miles out lay the cruisers and battleships. Pumping salvos of high explosive into the enemy batteries inland. Yet in spite of their noise, and sharper sounds of enemy shells and our demolition charges on the beach, in spite of the wreckage and movement of men and machines across the beach, you could not fail to see the beauty of the scene to seaward. The Channel was as blue as the Mediterranean, and as still. In the blue, cloudless sky above it floated hundreds of silver barrage balloons, twinkling in the sunlight.

A narrow, dusty road twisted up from the beach to the bluff. Up it wound a column of men and vehicles. They moved slowly over the steel road and past signs saying “Achtung, Minen,” keeping to the road, to the top. There, overlooking the beautiful seascape with its twinkling balloons, was a cluster of large mass graves, and near them were men digging fresh ones. Beside the road, a single soldier lay full-length on his face, his arms stretched above his head in an attitude of repose, a bullet hole through the top of his steel helmet. Behind the bluff to the right was a field hospital, where the slightly wounded were lying on the ground before the tents. The smell of ether crossed the road. There were several French women working in the hospital, but they were too busy to talk.

The poppies were bright

There were bright red poppies and some yellow flowers in the field near the hospital but dust was beginning to cover them over. Behind the hospital was a barbed-wire enclosure already packed with prisoners of war. Nearly 500 had come in by Wednesday afternoon, and more were on their way down from the forward units. Most of them were under 20 or over 40; they were well-fed, well-shod and fairly well-clothed; and all wanted water. A captain explained to a guard that they had been drinking local water for two or three years and they saw no reason to wait for the chlorinated water the Americans drank. The guard gave the captain a drink. Many of the men were not Germans, but Poles and Balts and Russians who had been put there to die in the first assault while the crack German divisions assembled farther behind. But the officers were German. All of them looked stolid and resigned, and even the youngest ones seemed to have lived longer than their captors.

Along the road inland from the bluff, columns moved forward in the dust. Above a mile and a half inland was a regimental command post, on a road at the edge of a thicket. This regiment had come ashore at 2:00 of the previous afternoon, D-Day, and so far, had seen only light fighting. The worst things were snipers and mines, said the regiment’s colonel. Those machine guns which had moved up to the bluff just before the attack had slipped back into the thickets and into farmhouses and were sniping at the roads. There were also many concealed riflemen, and another officer said he had fund snipers in a house all dressed like Frenchmen and speaking French. Mines were small antipersonnel mines that blew off a leg, and they were everywhere. The colonel wanted to know if there was any news from the Russians and looked disappointed when there was not.

There were some French people on the road, going back whence they had been evacuated when we took the village. They were very old, or children. One old man was swathed in bandages from the waist up. They all shook hands when they were spoken to in French, but none of them would stop to talk when they might be getting home again, and all of them cared more about getting home than about anything else.

Late in the afternoon, a regiment that had been resting beside the road moved up to attack with the rest of its division. But the battle of this beachhead was still being fought on the beach itself, and the battle was now as much against time as it was against the Germans. Troops and tanks and artillery moved ashore slowly through the wreckage and mines and shelling, and for miles offshore landing craft were waiting to get into the beach. Just before sunset, warships increased the tempo of their shelling and bombers dropped load after load on the places where the enemy artillery was thought to be, but still the enemy shells found their targets. Engineers fought all night against time and by dawn had cleared two more exits from the beach. More forces moved ashore. Whether they would be in time to meet the expected counterattack, no one knew.

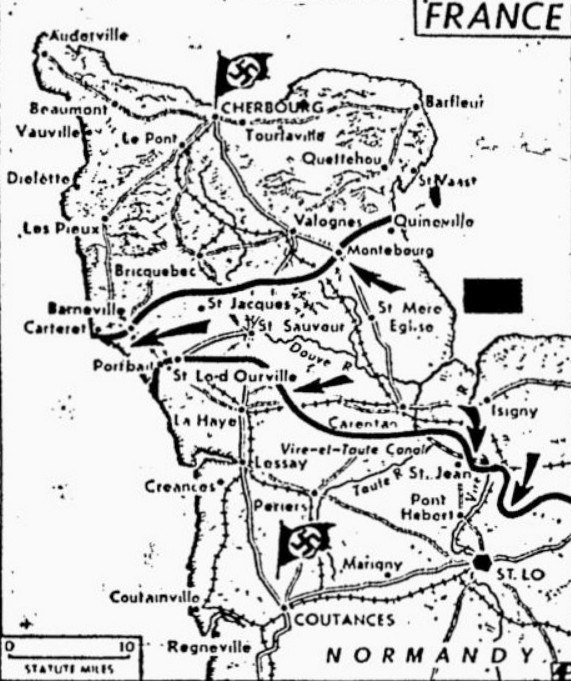

The western coast of Europe offered many landing places. Cherbourg Peninsula, riven by the valley of the Vire, was chosen because it commands the two best harbors – Cherbourg and Le Havre – between Brest and Rotterdam. The arrows show five Allied beach landings plus the raids, reported only by the Germans, on Guernsey and Jersey Islands and on the Calais district. Left arrows are mainly American; the right three mainly British. The Germans had long advertised that they expected invasion here. Hilly terrain is broken by small rivers cutting sharply through wooded farmland. Invasion has followed Vire and Orne rivers so far. The Seine still protects Le Havre, which will later become an objective if Cherbourg is cut off and taken.

The beachhead, as reported at week’s end, is shown in white on north coast of Normandy. The sea landings are indicated. Plane arrows show where the paratroopers and gliders are supposed to have landed in the continuing airborne campaign, by far the biggest such in the history of warfare. The main railway lines are shown. Allies had repeatedly cut line to Cherbourg at Bayeux, Carentan, and Sainte-Mère-Église. Germans claimed 20 Allied divisions opposed 10 German of the 7th and 15th Armies. Allied bombings pounded 25 German airfields in a 150-mile circle around the beachhead. Germans claimed to have identified 1st, 4th and 29th U.S., 7th and 9th British Armored, 50th British and 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions.

“Elsie” fleet (nicknamed from LC, or Landing Craft) sets out. In foreground is a box pontoon barge propelled by outboard motors. Pontoons can be fitted together to make dock. They bridge the water from ships to shore.

Men play cards on their way to France. They had each been given 200 francs to spend, but many lost the money before arrival. Said one, “I’ll borrow from Hitler.” One heavily armed soldier had a sign on his back, “Danger – Mine field.”

Protected by its own barrage balloons, invasion armada speeds along. In it were 4,000 ships, plus thousands of smaller craft. There were battleships, torpedo boats, submarines, minesweepers, cruisers, carriers and all kinds of landing ships. More of them were British than American.

The men listen to landing instructions. Before sailing, each soldier was given chewing gum, boxes of matches, a box of body insecticide, pipe, cigarette and chewing tobacco, water purification tablets, 12 seasickness pills and two vomit bags.

A box-pontoon barge is loaded down with trucks, tractor cranes, command cars and troops. Each vehicle has a name – Filthy Flora, Axis Doom, No Cum Chum, Adolph’s Answer, Ten Shilling Annie, For Ladies Only.

Under blankets two soldiers crawl to get out of the spray. As it usually does, the Channel made most of them queasy. Accordingly, they lost the meal of pork chops and plum pudding they had eaten on top of bacon and eggs before embarking.