The Afro-American (July 29, 1944)

Editorial: The postcard Democratic plank

That’s all, brother

The Democratic National Convention in Chicago last week adopted a postcard plank of 41 words on the race question. This is it, and for the sake of comparison, beside it are printed the Democratic plank of 1940 and the plank adopted by the Republicans:

1944 Democratic plank – Roosevelt-Truman (41 words):

We believe that racial and religious minorities have the right to live, develop and vote equally with all citizens and share the rights that are guaranteed by our Constitution. Congress should exert its full constitutional powers to protect those rights.

1940 Democratic plank – Roosevelt-Wallace (103 words):

Negroes

Our Negro citizens have participated actively in the economic and social advances launched by this administration, including fair labor standards, social security benefits, health protection, work relief projects, decent housing, aid to education, and the rehabilitation of low-income farm families.

We have aided more than half a million Negro youths in vocational training, education and employment.

We shall continue to strive for complete legislative safeguards against discrimination in government service and benefits, and in the national defense forces.

We pledge to uphold due process and the equal protection of the laws for every citizen, regardless of race, creed or color.

1944 Republican plank – Dewey-Bricker (108 words):

Racial and Religious Intolerance

We unreservedly condemn the injection into American life of appeals to racial or religious prejudice.

We pledge an immediate Congressional inquiry to ascertain the extent to which mistreatment, segregation and discrimination against Negroes who are in our armed forces are impairing morale and efficiency, and the adoption of corrective legislation.

We pledge the establishment by federal legislation of a permanent Fair Employment Practice Commission.

Anti-Poll Tax

The payment of any poll tax should not be a condition of voting in federal elections and we favor immediate submission of a Constitutional amendment for its abolition.

Anti-Lynching

We favor legislation against lynching and pledge our sincere efforts in behalf of its early enactment.

At first glance, it is evident that the 1944 Democratic plank is less than half as long as the other two.

In addition to its brevity, it is so general that it does not use the word Negro or colored. The party states its belief in equal rights and a vote for minorities as expressed in the Constitution, and adds that Congress should see that these rights are protected.

In 1940, the Democrats were far more specific in promising colored people (they used the word Negro then) legislation against discrimination in government service and in the Armed Forces. At that time, they also promised enforcement of all laws without regard to race, creed, or color.

By contrast, the 1944 Republican Convention plank, adopted in the same Chicago Stadium just a few weeks previously, not only condemned race and religious prejudice, but pledged (1) an investigation into mistreatment and segregation of colored people in the Armed Forced and legislation to remedy it; (2) a permanent Fair Employment Practice Commission; (3) a constitutional amendment to abolish poll taxes, and (4) a federal anti-lynching law.

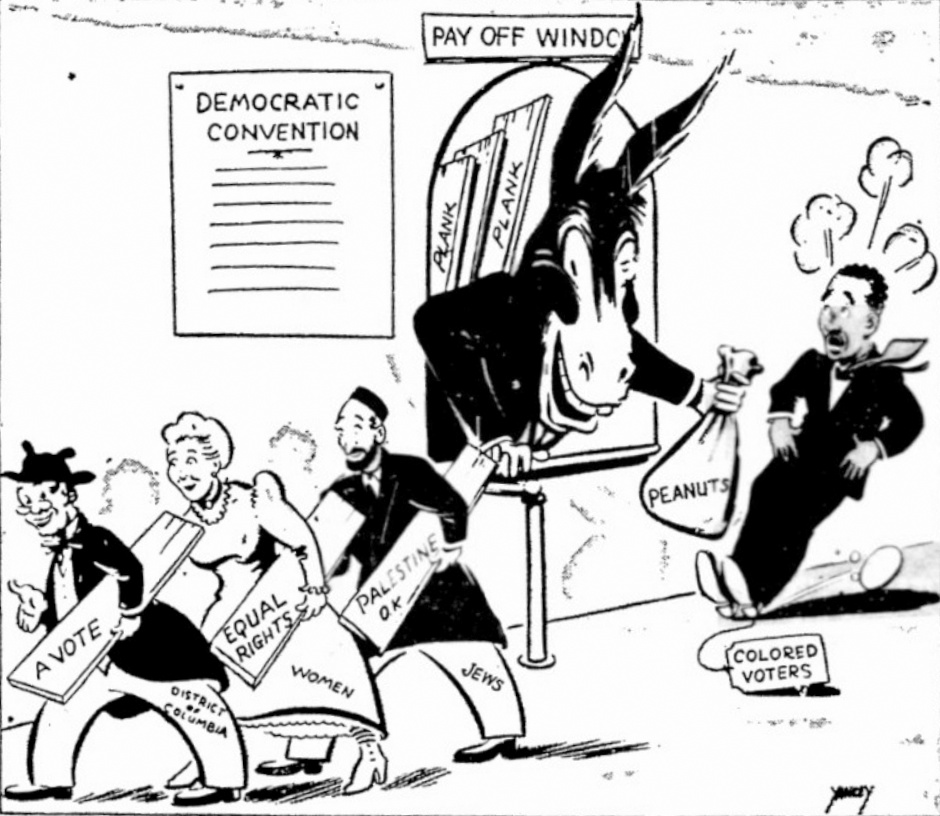

While the Democratic Convention substituted general and almost meaningless phrases on the color question, it was quite definite and specific on other matters.

For example, it favored (1) the opening of Palestine to unrestricted Jewish immigration and citizenship; (2) legislation guaranteeing women equal pay for equal work with men; (3) self-government for Alaska, Puerto Rico and Hawaii; (4) a vote for the citizens of the District of Columbia; (5) use of an international armed force to prevent future wars, and (6) a constitutional amendment on equal rights for women.

Why, then, was the Democratic Convention so definite and sure on those six issues mentioned above and so mealy-mouthed on the issues affecting the progress and welfare of colored people? Why did it say something in 1940 and little or nothing in 1944?

The answer is: the South. The Southern delegates who stand for segregation and white supremacy, came to the convention united upon the program of eliminating the “colored” plank altogether.

They did not succeed entirely but they did “cut and carve” the plank until it bears no relationship to the party’s stronger stand of 1940.

All told, the 1944 Democratic Convention plank is not only disappointing to colored Democrats, it is unsatisfactory to colored people.

Certain it is that the great Democratic Party which bid openly for the colored vote in 1940 has withdrawn the glad hand in just four years.