The U.S. Navy might well be grateful that it was not worse than it was, which one may assume it would have been if Donitz had been allotted the twelve boats he sought for the opening blow; and had Hitler not in February diverted twenty operational boats to reconnaissance duty off the coast of Norway, where he expected imminent British landings; and had not a particularly severe European winter frozen the Southern Baltic parts where scores of new boats were trapped while working up;’ and had not thirteen boats, including the now much-sought-after Type IXs, been lost in the ill-starred attempt to stop North Africa-bound convoys in the vicinity of Gibraltar.

If there were any consolations that the Allies could draw from the massacre on the American Main, it would seem that they were three in number: First, it occurred at just the time when the new Kriegsmarine four-rotor cipher Triton came into service fleet-wide, and as a result, except for three days, 23 and 24 February and 14 March, GC&CS went blind for eleven months. For the Allies to possess Enigma information during the period February-July would have granted them no special advantage, since the majority of U-boats, operating independently and transmitting infrequently, could not have been located regularly by cryptographic intelligence; nor could shipping have been diverted around them on the strength of Sigint. Of course, when the U-boat offensive returned to midocean convoy routes starting in August, and radio-directed patrol lines began forming again, the absence of Enigma was keenly felt.

Even then, Commander Winn’s Tracking Room was not without resources, which included access to the Heimische Gewässer (Home Waters) key, which continued to be used by the Kriegsmarine for Räumboot (motor minesweeper) escorts that shepherded U-boats in and out of the Biscay bases; penetration of the Tetis key used by new boats working up in the Baltic; RFP, or radio fingerprinting, which could identify an individual U-boat’s transmitter; TINA, an oscillographic operator signature device that displayed the specific keying style, or “fist,” of each U-boat Morse sender; HF/DF; and knowledge long assembled in the Tracking Room about BdU’s operating theory, characteristics of particular Commanders, U-boat routes, average speed of advance, and endurance at sea. From these remaining sources, plus Winn’s canny intuition, the Tracking Room developed daily an estimate, or “working fiction,” of U-boat operations.

The second consolation, to British strategists as much as to any like-minded officers in the USN, was the convincing demonstration in American waters of the value of convoy as a battle-winning expedient. And why was it so? Because either (I) the convoy drew U-boats to warships: instead of fruitlessly searching for the elusive craft—“hunting the hornets all over the farm”—the escorts had the U-boats in close proximity, where they could be attacked; or (2) the U-boats, unnerved by the hazards of attacking protected shipping, withdrew to more congenial waters, as happened in the American experience; or (3) attack opportunities declined mathematically, since if a U-boat was not correctly positioned to attack a convoy, it missed all the ships that formed it, and had to wait a long while for another chance.

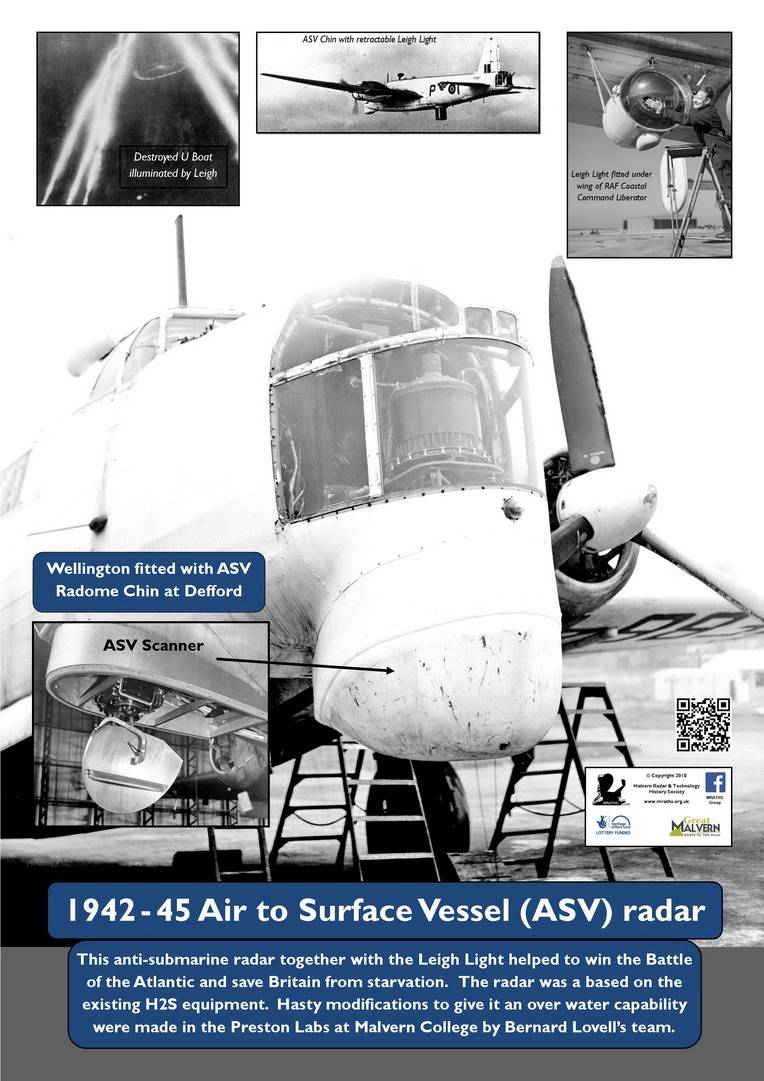

The third consolation that the Allies could take from the first half of 1942 was that the sea war in the west bought time for RAF Coastal Command and RN escorts to enlarge forces, improve training, and perfect tactics. It is to that opportunity, and to the role of the boffins, that our narrative now turns.

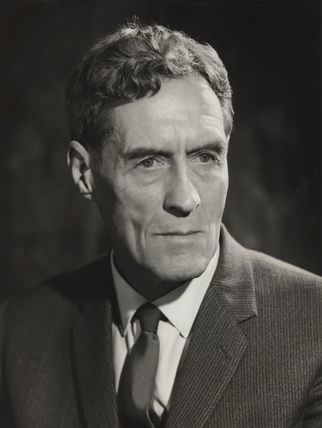

When in June 1941 Air Marshal Philip Joubert de la Ferté took command at Northwood, succeeding Air Chief Marshal Frederick Bowhill as Air Officer Commanding in Chief (AOC-in-C) RAF Coastal Command, he decided that he needed an advisor at his elbow in the operations room who was not a member of the uniformed service: a civilian scientist, privy to every operation and every command secret, who could give him objective, disinterested guidance on the day-by-day anti-U-boat war. In Joubert’s radical concept this civilian would advise on matters normally understood as being exclusively within the province of the RAF officer. His choice fell on Patrick M. S. Blackett, one of the most accomplished and versatile physicists of his day— “wonderfully intelligent, charming, fun to be with, dignified and handsome … married to one of the most delightful women in the world who did much to prevent him from becoming too serious.” An Royal Navy veteran of World War I, Blackett had given scientific advice to the Air Ministry during the mid-1930s when serving as a member of the shortlived “Tizard Committee,” chaired by physicist Henry Tizard. Other members of that body, which was largely responsible for the initiation of Britain’s radar network, were physiologist A. V. Hill and physicists H. E. Wimperis, A. P. Rowe, and F. A. Lindemann, later Lord Cherwell. This was a prototype “Operational Research Section,” a term that radar pioneer Watson Watt would later claim to have coined in 1940.

With Lindemann, whose presence on the Tizard committee was owed to pressure exerted by the then Mr. Winston Churchill, Blackett had a difficult relationship up to and throughout the war. In 1939–1940 Blackett worked with the Royal Aircraft Establishment (R.A.E.) at Farnborough, where he designed bombsights and other equipment that he personally flight-tested. With physicist Evan James Williams (1903–1945), whom he recruited to Farnborough, he worked on magnetic field detection of submarines. Blackett served seven months in 1940–1941 at the Anti-Aircraft (A.A.) Command at Stanmore, where he worked on gun-laying radar sets, until March 1941, when he received the call from Joubert.

Professor Patrick Blackett , later honored as Baron Blackett for his wartime services to Crown

Taking Williams with him, Blackett made it clear to Joubert that he had severed all connections to the design, manufacture, and testing of weapons. “From the first,” he wrote later, “I refused to be drawn into technical midwifery.” Instead, he would hold himself free for nonroutine investigations of a purely scientific nature; he would encourage numerical thinking on the conduct of operations; he would subject every assumption to quantitative analysis and empirical test; and thus he would “help to avoid running the war on gusts of emotion.” He rejected, too, the constant clamor of all the services for “new weapons for old.” What was needed at Coastal, he concluded, was for commanders, air crews, and maintenance personnel to make “proper use of what we have got.”

To that end he and Williams began scrutinizing every aspect of Coastal’s operations and asking or recognizing the importance of questions about even the blindingly obvious. To give an example: There had to be measurable explanations for what was then Coastal’s very low U-boat sighting rate and mere 1 percent kill rate of those boats sighted. A month after assuming his new position, Blackett paid a visit to Admiral Percy Noble’s Royal Navy Western Approaches operations room at Derby House, Liverpool, from which all British surface and air escorts were controlled; indeed, it should be pointed out that since March 1941, Coastal, while remaining an essential arm of the RAF, had been under the operational command of the Admiralty, the two services sharing responsibility for the air war against U-boats. The positions of escorts as well as the estimated positions of U-boats were displayed on an immense wall plot. A quick glance at Coastal Command aircraft positions and examination of their numbers of hours flown led Blackett to calculate on the back of an envelope the number of U-boats that should be sighted by the aircraft. Back at Northwood he checked actual sightings for that day and found them to be four times fewer than what he had calculated.

The reason eluded him until one day a Wing Commander asked casually, “What color are our aircraft?” Blackett recognized at once that that was the right question. RAF Coastal Command bombers, designed originally for night action over land, were painted black—a paint that made them stand out starkly against a North Atlantic cerulean blue or overcast sky, thus enabling an observant U-boat to dive before being sighted. Using first models and then aircraft, Blackett found that a white-painted bomber was sighted at 20 percent less distance than that at which a black aircraft was seen. Williams then calculated that a white aircraft would sight a surfaced U-boat on 30 percent more occasions than a black one, which should lead to an increase in sinkings. Within a few months all Coastal aircraft used on anti-U-boat patrols were repainted with matte white leading edges and under-surfaces.

A less simple problem, and one that became a classic in the early history of operations research, was that of depth charge (D/C) settings. The prevailing assumption at Coastal Command and the Admiralty was that on average, U-boats that sighted approaching aircraft could dive to a depth of about 100 feet before an attack could be delivered. Accordingly, depth charges were set to explode at that depth. The reasoning seemed flawless until Williams discovered (1) that if a boat had gotten that deep, it would also have traveled a certain distance horizontally, with the result that a bomber would not know where to drop his D/Cs; and (2) that in about 40 percent of attacks to date the boat was on the surface or had been submerged for no longer than 15 seconds, in which case 100-foot fuse settings rendered the D/Cs useless.

After some difficulty on Williams’s part in persuading Coastal officers that if the depth-setting adjuster was turned down to the 25-foot mark, the average number of U-boats sunk per given number of attacks would increase by two and a half times, the shallower setting was gradually introduced, starting with 50 feet in July 1941, progressing to 33 feet in January 1942, and reaching 25 feet in July of that year. The changes in setting were accompanied by a corresponding increase in lethality. Commented Blackett: “There can be few cases where such a great operational gain had been obtained by such a small and simple change of tactics.”

Under Blackett the Operational Research Section (O.R.S.) at Coastal grew into a tightly knit and formidable band of scholars, which included two future Nobel Prize winners (Blackett and John C. Kendrew), five future Fellows of the Royal Society (Blackett, Kendrew, Williams, C. H. Waddington, G. W. Robertson), and one future Fellow of the National Academy of Sciences of Australia (J. M. Rendel). With the exception of Blackett, who was forty-five in 1942, all were in their twenties and thirties. These and other O.R.S. members took on a wide range of problems affecting Coastal’s performance. Nine times out of ten the O.R.S. analysis found that existing operational assumptions and procedures were soundly based. Joubert’s staff had concluded, for example, that it was a better tactic to force a U-boat pack’s convoy shadower under the surface and thus disrupt the pack’s operation while it was being organized than to wait until after an attack was made to intervene.

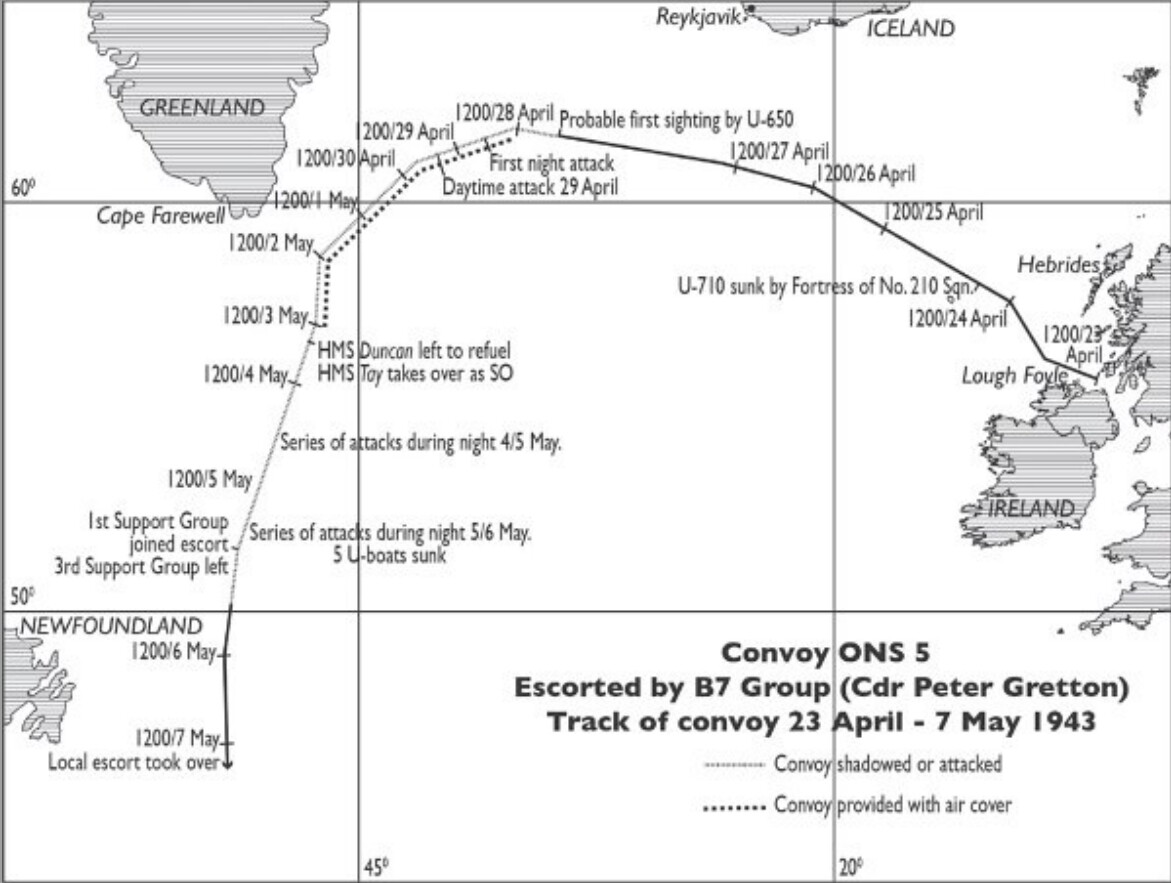

O.R.S. analysis was able to confirm and refine this tactic by showing that in order to do this, patrols must not be laid on too close to the convoy’s position. Studies had found, ironically, that most U-boat sightings had been made by aircraft that failed to meet their convoys. This led to the conclusion that most of a U-boat pack assembled more than twenty miles distant from the threatened convoy, and air patrols were vectored accordingly. During the period August 1942-May 1943, patrol at a distance yielded 40 percent more air attacks than continuous close escort (which was the American doctrine), greatly reduced sinkings by day, halved losses on the first night of a convoy battle and halved them again on the second, and detected a high density of boats behind the convoy, indicating that the work of the shadower had been frustrated and that the cohesion of the pack had been unhinged.

Blackett undertook additional studies of depth charge attacks (later continued by Dr. E. C. Baughan), which, like the 25-foot D/C setting, led to considerable improvement in lethality. Although Coastal personnel engaged in much discussion about bomb weight, some proposing D/Cs of 35, 100, or 600 pounds, Blackett was convinced that the current 250-pound weapon, with its 19–20 foot killing range, was perfectly serviceable if it was used correctly. He investigated its use under two categories: (1) aiming accuracy and (2) stick spacing. (A stick was a group of four to eight individual D/Cs dropped either all together as a salvo or, more often, in a series. In a series drop, an electromechanical intervalometer was used to establish the distance between the D/Cs, that is, “stick spacing.” The overall length of the D/C string was the “stick length.”)

For accuracy studies Blackett had a rear-facing mirror camera fitted to bombers and examined what the attack photographs showed, which was that pilots were placing the center of the stick length at a point 60 yards ahead of a surfaced U-boat’s conning tower. When asked why, pilots told him that it was “aim-off” to allow for the forward travel of the boat during the interval when the D/Cs were falling. This was in the manual; it was how they had been trained. But the photographs showed that the aim-off was not working. Blackett advised Joubert to have the pilots aim bang-on at the conning tower, even though it seemed to violate common sense. When they started doing so, kills increased by 50 percent.

The optimum stick spacing was a more complex problem, the resolution of which was not reached until after Blackett’s departure from Coastal Command in January 1942. Current practice of pilots was to set for 36 feet between charges, but mathematical analysis suggested that this was too short. The O.R.S. recommendation that the spacing be increased to 100 feet was accepted by the Coastal staff in March 1943, after which straddles of a U-boat with 100-foot spacing were increasingly lethal.

O.R.S. attacked many other problems, some as mundane as what came to be called Planned Flying and Maintenance, pursued by Dr. C. E. Gordon, whose aim was to make maximum possible use of crewmen and aircraft. Gordon found that in a typical squadron of nineteen aircraft only 6 percent of the time (in hours) was spent in the air; 23 percent on the ground even though crews were available and aircraft were operational; 30 percent in repair or maintenance; and 41 percent waiting on spare parts or manpower. If efficient use could be made of Coastal’s already existing resources, the force at sea could be greatly enlarged. Gordon’s “efficiency study,” as one would call it today, led to a near doubling of flying hours—a squadron of nineteen increasing from 1,300 to 4,000 hours—and proportionately greater peril to U-boats. The O.R.S. system was eventually adopted throughout the RAF and the Naval Air Division.

Other O.R.S. members, particularly the mathematicians, worked on more arcane problems, such as aircraft operational sweep rate and width; sighting ranges of various aircraft and of the various sighting positions within an aircraft; optimum altitudes for visual and radar searches; eye rest requirements for crew; probability-of-kill-given-sighting; open water navigation technique; the average number of convoys sighted by a U-boat during its lifetime (seven and a half), the average life expectancy of a U-boat (14 patrols), and development of what today would be called a “macro-model” of U-boat circulation in the North Atlantic. In January 1942, as earlier noted, Blackett left Coastal Command. His place as Officer in Charge was taken by Professor Williams. The section’s work continued as before, with what might be called even closer association of uniformed Command and civilian scientist after 6 February 1943, when Air Marshal Sir John Slessor succeeded Joubert as AOC-in-C of RAF Coastal Command.

Waddington testified that “At least in the sphere of my experience, I have rarely met such critical generosity of mind as was shown to us civilian ‘intruders.’” At no time, it appears, was there the slightest concern on the part of Joubert or Slessor that the “suck it and see” scientists sought an unwarranted prominence for themselves or ever considered themselves as anything other than members of a team.

In citing the contributions to Coastal of non-RAF personnel, special mention should be made of the senior Naval Liaison Officer, Commander, later Captain, D. V. Peyton Ward, R.N., who was the very embodiment of the close and fruitful relationship that existed between Coastal Command and the Admiralty. An invalided-out submariner, “P.W.,” as he was affectionately known at Northwood, volunteered for tasks not normally required of his position, and after Joubert’s arrival he took it upon himself to interview all returning aircrews who had sighted and/or sunk a U-boat. By writing up and analyzing each such incident, he greatly enlarged the attack data available to O.R.S. A navy-blue in the midst of RAF slate-blue, he represented Coastal Command on the important interservice U-Boat Assessment Committee, which judged the success of surface and air attacks. After the war, he wrote the official four-volume history of air operations in the maritime war. All the while O.R.S. and P.W. were bending their minds, the aircrews practiced their own difficult art of air search, hundreds of miles out over the Atlantic’s gray flannel, noisily patrolling 1,000 to 5,000 feet off the deck, in every kind of weather, dirty and cold, rarely if ever in their entire flight careers sighting a single U-boat to reward them for their protracted and boring hours. Said one crewman:

“It is difficult to describe the intense boredom of the sorties we undertook: hour after hour after hour with nothing to look at but sea. I am sure that when they found U-boats many crews pressed home their attacks regardless of what was being thrown at them, merely because it was a welcome relief from the boredom.”

And many crews would be shot down, in distant positions where no assistance was near or possible. And many other crews were lost to the sea not through enemy action, but through engine failure, adverse weather, navigational error, and fuel depletion.

Coastal Command’s motto was: “Constant Endeavor.”